Sounds Difficult: James Joyce and Modernism’s Recorded Legacy

Today’s post from Damien Keane marks the first in our recurrent series, “Live from the SHC,” which will broadcast the research of this year’s Fellows at Cornell University’s Society for the Humanities, directed by Timothy Murray, whose theme for 2011-2012 is “Sound: Culture, Theory, Practice, Politics.” The Society’s Fellows study a diverse range of sound studies topics: the relationship between sound and urban space, the moment when musical sound enters (and exits) the body, the sound of popular culture in interwar Egypt, the role of sound in constructing pious Muslim communities in secular European countries, and the manipulation of sound by “circuit benders”–to name just a few of the projects being researched up at the A.D. White House (To see the full list of Fellows, click here. To see the slate of SHC courses being taught at Cornell this year, click here). To allow our readers the opportunity to listen in to the goings on at the SHC, Sounding Out!‘s correspondent on the inside, Editor-in-Chief and SHC Fellow Jennifer Stoever-Ackerman, will be curating the online conversation amongst the fellows about their current research (and, of course, their sonic guilty pleasures)–so look (and listen) for it on selected Mondays from now through May 2012. –JSA

Today’s post from Damien Keane marks the first in our recurrent series, “Live from the SHC,” which will broadcast the research of this year’s Fellows at Cornell University’s Society for the Humanities, directed by Timothy Murray, whose theme for 2011-2012 is “Sound: Culture, Theory, Practice, Politics.” The Society’s Fellows study a diverse range of sound studies topics: the relationship between sound and urban space, the moment when musical sound enters (and exits) the body, the sound of popular culture in interwar Egypt, the role of sound in constructing pious Muslim communities in secular European countries, and the manipulation of sound by “circuit benders”–to name just a few of the projects being researched up at the A.D. White House (To see the full list of Fellows, click here. To see the slate of SHC courses being taught at Cornell this year, click here). To allow our readers the opportunity to listen in to the goings on at the SHC, Sounding Out!‘s correspondent on the inside, Editor-in-Chief and SHC Fellow Jennifer Stoever-Ackerman, will be curating the online conversation amongst the fellows about their current research (and, of course, their sonic guilty pleasures)–so look (and listen) for it on selected Mondays from now through May 2012. –JSA

—-

I began asking my students how many of them had turntables almost nine years ago, when, as a graduate student teaching a course on the twentieth century, I found myself seventy pages into Dracula and having to explain what a phonograph is: then, only one or two hands went up, or half-up, in response to the question. A year ago, when I put this question to students in a course on modernism, fully two-thirds of the thirty-five students in the room raised their hands – although more than a few of them also believed that Steve Jobs had invented the mp3. Even allowing for self-selection and/or misrepresentation on their part, and for a soft form of administrative research and/or miscounting on my part, this swing is quite dramatic.

But what I find intriguing about the uptick is how it tracks with an equally dramatic rise in the use of a kind of allusion in commentaries about the effects of digital media on education. I am referring to those parenthetical asides that so often follow mention of residual technologies such as turntables and albums (e.g. “anyone remember those?”). While these asides are delivered in the manner of a stand-up comic doing material about blind dates or the post office, they serve to euphemize powerful attitudes about technology and what it is to be modern that are even less funny than such shtick, perhaps most directly by assuming the unqualified and unimpeachable newness of the present. Asking if anyone remembers the record player – or the chalkboard or the library or the secretarial staff – takes for granted that you’ve already taken it to the next level, having left off your turntable with parietals and rumble seats.

The limited edition of Joyce's _Anna Livia Plurabelle_ (1928). All further images by the author, Damien Keane

Which brings me to the gramophone recording that James Joyce made of the ending of Anna Livia Plurabelle, an episode of what would eventually become Finnegans Wake. Joyce had begun publishing pieces of his work in progress in 1924, and the Anna Livia Plurabelle section was by far the most visible of these, having appeared in several variant forms by the turn of the decade. Among these were its publication as a stand-alone, limited edition book in 1928, and the release of the recording that had been made at C.K. Ogden’s Orthological Institute in Cambridge, as a double-sided twelve-inch gramophone disc in 1929. Each did surprisingly well, and in tandem they helped to secure acceptance of Joyce’s formally challenging aesthetic procedures among readers. Indeed, some in the literary field, such as T.S. Eliot, hoped that recordings of authors’ readings would soon supplant, or at least augment, the market for limited and deluxe editions.

The fact that recordings did not replace books would be of little interest now, were it not for the way that their relationship in 1929 neatly conjures the supposedly defining trait of our own moment: the demise of one media epoch and the emergence of another (and with economic catastrophe at hand, too). Yet it is the gramophone recording – the “new media” format of that past moment – that is considered thoroughly obsolete today. What then can be said about the “listening history” of the recording? How has the sound of Joyce’s recorded reading interacted with perceptions of the readerly difficulty of the text, which, whether rightly or wrongly, are the pre-eminent “mode” through which readers approach Finnegans Wake? Put simply, if reading the text is hard, is listening to a recorded reading of that text hard?

.

In thinking about these questions, what catches my attention is the slippage between different senses of “difficulty,” between the positive inflections of literary difficulty and the negative connotations of sonic interference. Contemporary listeners tend to emphasize the crackles and pops that compete with the sound of Joyce’s voice and its language, and thereby locate the “difficulty” of the recorded reading in the sound of the recording itself. It is as though the recording medium actually impedes access to Joyce’s language or somehow imposes itself between the listener and his voice – despite the fact that the medium enables this access in the first place. This is to say, the “low” fidelity of the recording of Joyce’s voice simply cannot reproduce the literary experience of Joyce’s prose, that most elusive, or rarified, object of speculation. (Is it the singularity of literature or is it Memorex?) Today’s default reaction to the recorded reading might be juxtaposed to a much earlier response, Hazel Felman’s setting of the very end of the passage for piano and voice, published in 1935. Here is her explanation of the genesis of her composition:

The emotional reaction I experienced on hearing a recording which James Joyce made of the last pages of ANNA LIVIA PLURABELLE was profound. As I listened to the record time and again, the conviction grew upon me that if I could re-create in music the mood that the author creates when he reads the closing chapters of ANNA LIVIA PLURABELLE, I would be justified in translating into a musical idiom what already seemed to be sheer music.

Felman’s response pivots on the aural clarity of the Anna Livia Plurabelle recording – she notes, for example, that D is used as a pedal point in the setting because Joyce’s voice modulates around a pitch of D in the recording – and the “sheer music” she heard there was mediated by that very recording.

Almost eighty years after Felman, today’s hi-fi listeners more often hear in the recording only a poor realization of Joyce’s text, a judgment that has nothing to do with Joyce’s performance and everything to do with the grossly uneven staking of the recording’s semiotic content against its materiality. Yet we do well to recall that surface noise is just as “modernist” as Joyce’s innovative prose. Why do we always forget that? To ask this question brings us back to turntables and students. (Anyone remember them?)

—

Damien Keane is an assistant professor in the English department at the

State University of New York at Buffalo. He is nearing the completion of

a manuscript entitled Ireland and the Problem of Information.

Hearing the Tenor of the Vendler/Dove Conversation: Race, Listening, and the “Noise” of Texts

In the beginning there were no words. In the beginning was the sound and they all knew what the sound sounded like. –Toni Morrison, Beloved

A conversation in my Black Feminist Theories class on the two versions of Sojourner Truth’s famous speech from the Ohio Women’s Convention—the one published in 1863 that renders her words in a black southern dialect or the 1851 version that does not—elicited the following story about listening. A black male student was student teaching/observing in a classroom — the teacher was white, the student teacher black. The exercise he observed involved transcribing speech and then reading it back. A black male student in the classroom spoke and the white teacher and black student teacher each transcribed the speech and read their transcriptions aloud. The white teacher’s transcription/recording was in dialect, the black student teacher’s was not. The student teacher maintained that what and how the white teacher heard the black student was not, in fact, either what or how the black student spoke.

Discussions like these have spurred me to meditate more deeply on sound. And now that I’ve really begun to consider it, texts have become much noisier places; the white spaces and black marks becoming places for reading and hearing. Thinking more deeply about sonic affinities and communities has helped me really begin to understand how sound shapes sight and sight shapes sound.

An example: Since reading Fred Moten’s In the Break, in particular “The Resistance of the Object,” it’s not only impossible for me to read the scene of Captain Anthony’s beating/rape of Aunt Hester in Frederick Douglass’s Narrative without hearing Abbey Lincoln’s hums, moans, and screams, it is not possible for me to read the entire text without populating it with sound, even as those sounds are, in my imagining of them, not always specific.

.

Perhaps it’s most accurate to say that I am aware that the world that the text references is a world filled with sounds peculiar to it, many of which may no longer be present in our contemporary world. At the same time, I try to bring at least some of those sounds—talking drums, field hollers, whips cracking, the sounds of chains, etc.—and approximations of sounds into the classroom when I teach Douglass’s Narrative and My Bondage and My Freedom (as well as when I teach other texts).

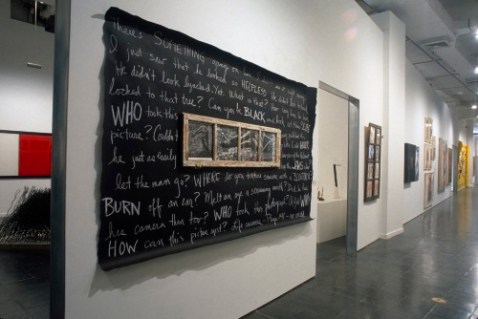

In “The Word and the Sound: Listening to the Sonic Colour-line in Frederick Douglass’s 1845 Narrative” (2011) Jennifer Stoever-Ackerman writes, “The emphasis Douglass places on divergent listening practices shows how they shape (and are shaped by) race, exposing and resisting the aural edge of the ostensibly visual culture of white supremacy, what I have termed the “sonic colour-line” (21). Stoever-Ackerman riffs on Elizabeth Alexander’s “Can you be BLACK and Look at This: Reading the Rodney King Video” (and Alexander riffs on Pat Ward Williams’s “Accused, Blowtorch, Padlock”) to ask, “Can you be WHITE and (really) LISTEN to this?” or alternatively, “Are you white because of HOW you listen to this?” (21).

Pat Ward Williams's "Accused/Blowtorch/Padlock" (1986), Courtesy of the Artist and the New Museum, New York

.

In his review of Shane White and Graham White’s The Sounds of Slavery: Discovering African American History Through Songs, Sermons, and Speech (Beacon Press, 2005) in the July 2009 issue of the Journal of Urban History, Robert Desrochers contrasts the abolitionists who were attuned to how to make a white audience hear the sounds that surrounded and produced the (performances of the formerly) enslaved, to the “Virginia patriarch who failed to mention the singing of his slaves even once in a diary that ran to hundreds of manuscript pages” (754). Given these examples of the ways that many white ears had to be systematically attuned to hearing slavery’s sounds as well as the understanding that, “the very things that made slave sounds distinctive—chants, grunts, and groans; melismatic, repetitious, and improvisational lyric play; pitch and tonal inflections and cadences; timbral variations, polyrhythms, and heterophonic harmonies—struck whites mostly as strange, inappropriate, wrong” (754)—the answers to Stoever-Ackerman’s questions may be respectively “no” and “yes” (or several combinations of no and yes), particularly if we engage “whiteness” as an ideology and not simply (or not only) a “raced” description of those people constituted socially and legally as (presumably) white.

It was with these kinds of questions of sound and sonic whiteness on my mind (especially this question of who hears, who doesn’t hear, and then again what is and isn’t heard) that I read and was brought up short by Helen Vendler’s recent November 24, 2011 New York Review of Books review of Rita Dove’s The Penguin Anthology of 20th Century American Poetry. In this piece, Vendler takes Dove to task for what she considers the anthology’s over-inclusiveness (“No century in the evolution of poetry in English ever had 175 poets worth reading”), the “accessibility” of the poems (“short poems of rather restricted vocabulary”), and the appearance of a large number of black and other non-white poets in the latter part of the twentieth-century. In short, from Vendler’s perspective, Dove is choosing “sociology” and complaint over artistry; mixing the wheat and the chaff.

It was with these kinds of questions of sound and sonic whiteness on my mind (especially this question of who hears, who doesn’t hear, and then again what is and isn’t heard) that I read and was brought up short by Helen Vendler’s recent November 24, 2011 New York Review of Books review of Rita Dove’s The Penguin Anthology of 20th Century American Poetry. In this piece, Vendler takes Dove to task for what she considers the anthology’s over-inclusiveness (“No century in the evolution of poetry in English ever had 175 poets worth reading”), the “accessibility” of the poems (“short poems of rather restricted vocabulary”), and the appearance of a large number of black and other non-white poets in the latter part of the twentieth-century. In short, from Vendler’s perspective, Dove is choosing “sociology” and complaint over artistry; mixing the wheat and the chaff.

Vendler writes, “Rita Dove, a recent poet laureate (1993–1995), has decided, in her new anthology of poetry of the past century, to shift the balance, introducing more black poets and giving them significant amounts of space, in some cases more space than is given to better-known authors. These writers are included in some cases for their representative themes rather than their style. Dove is at pains to include angry outbursts as well as artistically ambitious meditations.”

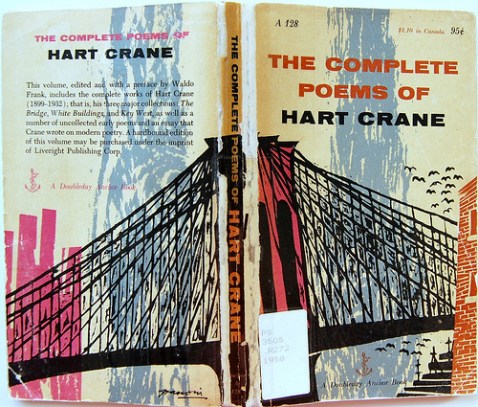

And Vendler on Dove on Hart Crane: “sometimes one wonders whether Dove is being hasty. She speaks, for instance, of ‘the cacophony of urban life on Hart Crane’s bridge.’ But the bridge in his ‘Proem’ exhibits no noisy ‘cacophony’; its panorama is a silent one. The seagull flies over it; the madman noiselessly leaps from ‘the speechless caravan’ into the water; its cables breathe the North Atlantic; the traffic lights condense eternity as they skim the bridge’s curve, which resembles a ‘sigh of stars’; the speaker watches in silence under the shadow of the pier; and the bridge vaults the sea. The automatic—and not apt—association of an urban scene with noise has generated Dove’s ‘cacophony.’”

Why does Vendler insist on silence where Dove joins sight and sound? That Vendler imagines silence and takes Dove to task for attaching cacophony to the city scene in the bridge poem is a struggle over meaning, over epistemology and ontology. How is Vendler registering not only the poem but also the entire text differently? This isn’t the only instance of Vendler’s insistent sonic “whiteness” whereby and wherein the reading of the poem, the anthology, and the anthologizer herself are disciplined.

Speechlessness though, is not soundlessness, and it seems to me that Dove locates herself on the bridge (and in the soundscape of the contemporary written poem) such that she hears the water, the seagull, and the leap and curve and flap of gull and man. As Dove herself responded (also in the New York Review of Books), “A cursory sweep over just the section [Vendler] excerpted in my anthology yields a host of extraordinary sounds: what with trains whistling their “wail into distances,” chanting road gangs, papooses crying—even men crunching down on tobacco quid—my gasp of surprise at Vendler’s blunder can barely be heard.”

In Vendler’s remarks and Dove’s response we might read the kind of cultural dissonance that continues to both construct and give insight into how different communities of readers and listeners are formed and the ways they are and aren’t racialized. By the end of the review, Vendler wants to be heard by those whom she imagines as the anthology’s likely readers: she wants to turn to them and “say,” to “cry out,” that there are better poems than those included here. For the sounds that in this anthology that Vendler hears most often in the “minor” poems, in the “minority” poets, and the “minority” anthologizer, are simplicity, noise, and needless complaint. And Vendler and Dove have been here before – see Vendler on Dove and Delaney on Vendler and Dove.)

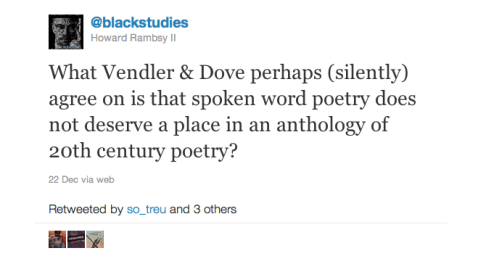

But despite the debate putting poetry front and center and enacting ways that it matters, Vendler’s critique and Dove’s response are each conservative, though in quite different ways. Neither Vendler nor Dove in the review, anthology, and defense of the anthology imagines the inclusion of spoken word, hip-hop (see Howard Rambsy II), and other forms of contemporary rhyme and verse that speak to a broad range of audiences across race, sex, and class. The inclusion of rap might further change the tenor of the conversation, opening up in important ways the debate over what counts as poetry, and expanding how black musical and poetic forms are heard and by whom.

—

Christina Sharpe is Associate Professor of English and American Studies at Tufts University where she also directs American Studies. Her book Monstrous Intimacies: Making Post-Slavery Subjects was published in 2010 by Duke University Press. Her current book project is Memory for Forgetting: Blackness, Whiteness, and Cultures of Surprise.

Recent Comments