Afrofuturism, Public Enemy, and Fear of a Black Planet at 25

Twenty-five years after Do the Right Thing was nominated but overlooked for Best Picture, Spike Lee is about to receive an Academy Award. At the beginning of that modern classic, Rosie Perez danced into our collective imaginations to the sounds of Public Enemy. Branford Marsalis’s saxophone squealing, bass guitar revving up, she sprung into action in front of a row of Bed-Stuy brownstones. Voices stutter to life: “Get—get—get—get down,” says one singer, before another entreats, “Come on and get down,” punctuated by James Brown’s grunt, letting us know we’re in for some hard work. In unison, Chuck D and Flavor Flav place us in time: “Nineteen eighty-nine! The number, another summer…” The track’s structure, barely held in place by the guitar riff and a snare, accommodates Marsalis’s saxophone playing continuously during the chorus, but intermittent scratches and split-second samples make up the plurality of the sounds. The two rappers’ words take back the foreground in each verse, and their cooperative and repetitive style reinforces the song’s message during the chorus, when they trade calls and responses of “Fight the power!”

.

Throughout the credits, lyrics and musical elements are shot through with noise: machine guns, helicopters, jet engines—even the sax, the only conventional instrument at work, seems to cede ground to these disruptions. The dancing form of Perez, unlike the other figures taking part in the performance, is silent but visible; she’s the only one who seems fully in control of the relationship between her body and the sounds. Perez’s performance of “Fight the Power” is an antidote to fantasies of masculine technological mastery: her movements, while sometimes syncopated, are discrete to the point of appearing martial—the steps are improvised but the skills are practiced; she’s ready to step into the ring.

Fulfilling Spike Lee’s request to Public Enemy to provide a theme for the movie, “Fight the Power,” made it onto the group’s iconic album Fear of a Black Planet the following year. In Anthem, Shana Redmond names the song “perhaps the last Black anthem of the twentieth century,” noting that it bridges divides like the space between America’s East and West Coasts (261-262). It does so as part of the film’s opening sequence through juxtapositions: the sound of helicopters, a signature of LAPD surveillance, crosses the New York City streetscape in stereo. On the album, however, a radically different opening sets the tone for the track. A speech by Thomas Todd taunts, “Yet our best trained, best equipped, best prepared, troops refuse to fight. Matter of fact, it’s safe to say that they would rather switch than fight.” The speaker draws out the breathy, sibilant ending of the word “switch” to create a double entendre; voiced this way, “they would rather switch” connotes both disloyalty in the “fight” and a swishy movement of the hips attributed to effeminate men. In later years, the crystal-clear sample would resurface across genres; it was the only lyrical component of DJ Frankie Bones’s “Refuse to Fight” in 1997, a track purely intended for dancing in the blissful atmosphere of the rave scene, which evacuated militancy to make room for “Peace, Love, Unity, and Respect.”

On PE’s album, the version of the song introduced by this sample strikes a stark contrast with its rendition in the film as the vehicle for an inexhaustible and defiant female dancer in a neighborhood wracked by disempowerment.

Identifying Fear of a Black Planet as “the first true rap concept album,” Tom Moon of the Philadelphia Inquirer recognizes the role of the DJ and production team in achieving its unique synthesis between melodic and meaning elements. At first he calls the sample-heavy stage for the rap performance “a bed of raw noise not unlike radio static,” but he later parses out how this “noise” actually consists of a rich informational emulsion:

an environment that can include snippets of speeches, talk shows, arguments, chanting, background harmonies, cowbells and other percussion, drum machine, treble-heavy solo guitar, jazz trumpet, and any number of recorded samples.

The underlying concept driving the album is the ominous encounter between Blackness and whiteness, which has become an object of fear and fascination throughout centuries of American culture. As the role of their anthem in the film about a neighborhood undergoing violent transformation indicates, the meeting of Black and white is not a fearsome future to come, but a present giving way to both reactionary and revolutionary possibilities. And it goes a little something like this.

In this post, I provide track-by-track sonic analysis to show how, over the past 25 years, Fear of a Black Planet has contributed to Afrofuturism through its invocation of prophetic speech and through its place on the cultural landscape as a touchstone for the beginning of the 1990s. As the first song, “Contract on the World Love Jam,” insists, in one of the “‘forty-five to fifty voices’” Chuck D recalls sampling for this track alone, “If you don’t know your past, then you don’t know your future.”

This moment continues to resonate in the present as a repository of ideas and modes of expression we still need. Along with the hypnotic efficacy of rhetoric like “Laser, anesthesia, ‘maze ya/ Ways to blaze your brain and train ya,” and Flavor Flav’s subversive humor, I argue that Fear of A Black Planet engages with Afrofuturism by using sound to instigate the kind of “disjuncture” that Arjun Apparurai called characteristic of culture under late modern global capitalism. This kind of practice thematizes Fear of a Black Planet: it uses sound to confront the boundaries of information, desire, and power on decisively African Americanist terms. PE cut through the noise with a new sound, one that still resonates 25 years later.

Sampling is an indispensable strategy on Fear of a Black Planet. Yet as Tricia Rose contends, the sound of hip-hop arises out of a systematic way of moving through the world rather than as a “by-product” of factors of production. In Capturing Sound, Mark Katz identifies Public Enemy’s sampling with “the predigital, prephonographic practice of signifying that arose in the African American community” (164). Scholars and music critics alike have dubbed this era the “golden age” of digital sampling, a moment when new technology made it possible for musical composition to rely on audio appropriated from a panoply of sources but before the financial and methodological obstacles of copyright clearance emerged in force. As Kembrew McLeod and Peter Di Cola argue in Creative License, challenges imposed by the cost of licensing fees now associated with sampling make contemporary critics doubtful that Black Planet could be produced today (14). In retrospect, the album shows us how the “financescape” of popular music has evolved out of sync with the technoscape: by placing property rights in the way of the further development of the tradition inaugurated by the Bomb Squad (PE DJs Terminator X, Hank Shocklee, Keith Shocklee, and Eric “Vietnam” Sadler).

In 2011, when asked by NPR’s Ira Flatow about sampling as an art form, Hank Shocklee pointed out that, “as we start to move more toward into the future and technology starts to increase, these things have to metamorphosize, have to change,” further insisting that this means, “everything should be fair use, except for taking the entire record and mass producing it and selling it yourself.” Realizing how sampling entails not just the use of sound but its transformation, he stakes out a radical position on intellectual property, noting that the law tends to protect record companies rather than performers:

Stubblefield, [the drummer], is not a copyright owner. James Brown is not a copyright owner. George Clinton is not a copyright owner. The copyright owners are corporations… when we talk about artists, you know, that term is being used, but that’s not really the case here. We’re really talking about corporations.

Driven by such a skeptical orientation to the notion of sound as property, Fear of a Black Planet is both unapologetic and unforgiving in its sonic promiscuity. It weds a dizzying repertoire of references from the past to a sharp political critique of the present, embodying the role of hip-hop in transforming the relationship between sound and knowledge through whatever means the moment makes available.

A different Spike Lee joint (Jungle Fever, 1991, with a soundtrack by Stevie Wonder) enacts the spectacle behind the title track on Fear of a Black Planet. Interracial sexuality, as one of many dimensions of living together across the color line, is the most explicit “fear” a Black Planet has in store, but two tracks undercut the flawed notions of white purity at the heart of the issue.

Chuck D dismisses the concerns of an imaginary white man at the start of each verse: “your daughter? No she’s not my type… I don’t need your sister… man, I don’t want your wife!” He subsequently shifts focus to the questions of “what is pure? who is pure?” what would be “wrong with some color in your family tree?” and finally, whether it might be desirable for future generations to become more Black, owing to the adaptive value of “skins protected against the ozone layers/ breakdown.” Chuck’s line of questioning assuages the anxiety that the imagined white interlocutor might feel in order to address more fundamental planetary concerns, like environmental degradation. In addition to staging a conversation in which a Black man enjoins a white man to listen to reason, the structure of the track involves Flavor Flav in a parallel dialogue. Flav replies to each of Chuck’s initial reassurances the same playful counterpoint: “but suppose she says she loves me?” He keeps posing the hypothetical in one verse after another, despite Chuck D’s repeated insistences that he isn’t interested in white women, suggesting that “love,” an irrational but undeniably powerful motivation for interracial encounter, is just as compelling as a putatively rational browning of the planet’s people. “Pollywannacracka” riffs on the same subject with hauntingly distorted vocals and a chorus that includes a mocking crowd calling the Black woman or man who desires a “cracka” out their name (the drawn out refrain is the word “Polly…”) and a teasing whistle. These derisions reduce the taboo topic of interracial liaisons to the stuff of schoolyard taunts while playing out tense confrontations among Black men and Black women in between the verses.

Black Planet also presented PE the first opportunity to reconstruct their reputation after former manager, Professor Griff, made anti-Semitic comments–“Jews control the media”—in an interview. PE takes the public’s temperature on “Incident at 66.6 FM,” which reiterates snippets from listeners calling in to radio broadcasts; most of the callers represented excoriate the group but a few defend them, including erstwhile DJ Terminator X, who shouts himself out.

This inward-facing archive acquires more material on the album’s most self-referential track, “Welcome to the Terrordome.” The song elliptically places the scrutiny the group has faced in perspective through allusions that are rendered even more involuted through repetition and internal rhyme: “Every brother ain’t a brother… Crucifixion ain’t no fiction… the shooting of Huey Newton/from the hand of a nig that pulled the trig.” The brother who allegedly ain’t one was David Mills, the music journalist who publicized Griff’s comments.

Noting Chuck’s rather transparent analogy between this betrayal and the myth that the Jewish community was responsible for killing Jesus, Robert Christgau, in Grown Up All Wrong, concludes that “the hard question isn’t whether ‘Terrodome’ is anti-Semitic—it’s whether that’s the end of the story” (270-271). It isn’t. “War at 33 1/3” redraws these same lines by advising that “any other rapper who’s a brother/Tries to speak to one another/Gets smothered by the other kind,” hearkening back to the earlier song’s assertion not all skinfolk are kinfolk. The song samples speech from Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan that frames the titular “war” as a rhetorical contest.

The most collaborative jam on the album, co-written by Rage Against the Machine’s Zack De La Rocha, “Burn Hollywood Burn” enacts an acerbic critique of media representations of Blackness against the most party-perfect hooks on the album, including a sampled crowd repeating the three words of the refrain like a protest chant, a timeline provided by a pea whistle, and a horn sample looped for the gods.

Sustaining a militant ideal of Black masculinity in defiance of Hollywood’s Stepin’ Fetchit and Driving Miss Daisy scripts (both referenced by name), featured MCs Ice Cube and Big Daddy Kane occupy the track’s. Their forward-leaning posture demands they be taken seriously, like Chuck D, rather than coming off as whimsical and indulgent like Flavor Flav. Yet PE’s sound would be unrecognizable without Flav’s flavor to carry out the call-and-response structure of their performances. Flav voices a skit on the final verse of “Burn Hollywood Burn” in which he is invited to portray a “controversial Negro” as an actor; he asks if the role calls on him to identify with Huey P. Newton or H. Rap Brown, but to his chagrin, the invitation calls for “a servant character that chuckles a little bit and sings.” Contemporary audiences might associate Flavor Flav with the latter based on his reality TV persona, but the comic wit he brings to PE knowingly undermines strident posturing and demands that the audience listen more closely.

“Flavor Flav of Public Enemy at Way Out West 2013 in Gothenburg, Sweden” by Wikimedia user Kim Metso, CC BY-SA 3.0

Despite the comparatively trivial content of his lyrical presence on most tracks, Flav enhances the repertoire of knowledge at work across Fear of a Black Planet, deepening its cultural frame of reference and accentuating different elements of its sonic structure. On “Who Stole the Soul,” for example, after Chuck says, “Banned from many arenas/ Word from the Motherland/ Has anybody seen her,” Flav repeats after him, “Have you seen her,” emphasizing the allusion to ”Have You Seen Her?” by the Chi-Lites. Then, before Chuck has finished his next line, Flav repeats himself, stylizing the question “Have You Seen Her” with the same melody used by the Chi-Lites. Ingeniously, Flav modifies the allusion that Chuck makes in verbal form by using the timing and melodic structure of his repetition to produce a new timeframe within the existing track, doubling the ways in which this line alludes to a prior work.

On his own, Flav’s performances on Black Planet laugh through the pain of urban dystopia, the. concentrated poverty, premature death, and alienation from the amenities of citizenship he explores in “911 is a Joke” and “Can’t Do Nuttin’ For Ya Man.” “911” is especially notable for coupling Flav’s cynical appraisal of life and death in the hood to repetitive verse structures, a tight rhyme scheme consisting mostly of couplets, a chart-ready beat (the song reached #1 on the Billboard Hot Rap Singles list), and an unforgettable quatrain as the hook: “Get up, get, get, get down/911 is a joke in your town/ Get up, get, get, get get down/Late 911 wears the late crown.”

.

The notion of getting down to misery is disturbing, but that’s all you can do. The track ends with a particularly macabre sample: the laughter of Vincent Price, the same heard at the harrowing conclusion of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.” “Can’t Do Nuttin’ For Ya Man,” on the other hand, ends with Flav’s raspy laughter. While “911” ironizes the withdrawal of public resources from “your town” amid concentrated poverty, this song sends up the misfortunes urban denizens bring on themselves. The funky tune profanes the serious concerns of a man who’s fallen into a life of crime, offering no Chuck D-style self-help just “bass for your face.”

Mark Anthony Neal has called the generation that came of age in the 1990s the “Post-Soul” generation, and the many funk and soul references on Fear of a Black Planet, from the preceding sounds to the rallying cry of “Who Stole the Soul,” connect the first hip-hop of the 1990s to the prior generation of Black music. Repetition with difference allows the group to maintain a dialogue between their precedents in socially conscious popular music and the new intervention they intend to make. If “Fight the Power” signals the dawn of new era, so does the largely-forgotten “Reggie Jax,” the downtempo freestyle on which Chuck D coins the term “P-E-FUNK.”

Chuck’s neologism, which he introduces by spelling it out, “P-E-F-U-N and the K,” is a performative citation linking PE’s brand of hip-hop to the P-Funk of the 1970s: perhaps the defining expression of Afrofuturism in popular music. The morphology of “P-E FUNK” is highly novel, infixing a new element within an existing word and also facilitating the flow between the terms by enunciating their assonant sounds. This tactic for naming the fusion of hip-hop and P-Funk allows PE to continue a pattern initiated by their predecessor Afrika Bambaataa, whom they sample on “Fight the Power,” by inserting themselves into a particular artistic genealogy (traced by Ytasha Womack in Afrofuturism) animated by George Clinton, Bootsy Collins, and the mind-expanding antics of Parliament/Funkadelic.

Still from Public Enemy video for “Do You Wanna Go My Way?”

The intense polyrhythmic edifice of Fear of a Black Planet link past to (Afro)future, engaging in a radically heteroglossic practice of treating sound as information. Deploying the sound of knowledge and the knowledge of sound in the service of envisioning the world as it is, the album charts a dystopian itinerary for the 1990s that we need to comprehend how we arrived at the present. Rather than worrying that a Black Planet is something to fear, we might consider the lessons that emerged from past efforts to cope with developments already underway. If we listen to Flavor Flav and find that coping strategies are futile, at least we can party. And if we were right to call Chuck a prophet, then the dawn of the Black Planet he warned us about—characterized by neoliberal governance, gentrification, and boundaries that demand to be crossed—is a moment when the avant-garde tactics of Afrofuturism are becoming important to everyone. Citizens of Earth: Welcome to the Terrordome.

—

andré carrington, Ph.D., is Assistant Professor of African American Literature at Drexel University. His research on the cultural politics of race, gender, and genre in popular texts appears in journals and books including African and Black Diaspora, Politics and Culture, A Companion to the Harlem Renaissance, and The Blacker the Ink: Constructions of Blackness In Comics and Sequential Art. He has also written for Callaloo, the Journal of the African Literature Association, and the Studio Museum in Harlem. His first book, Speculative Blackness: The Future of Race in Science Fiction, is being published by University of Minnesota Press.

—

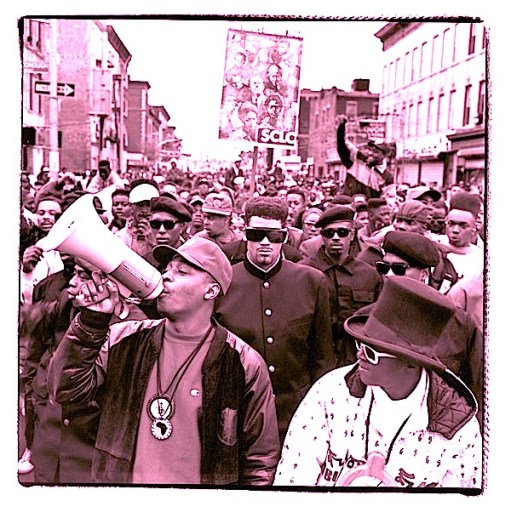

Featured Image: Still from “Fight the Power” video, color altered from b & w by SO!

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Straight Outta Compton… Via New York — Loren Kajikawa

Fear of a Black (In The) Suburb — Regina N. Bradley

They Do Not All Sound Alike: Sampling Kathleen Cleaver, Assata Shakur, and Angela Davis — Tara Betts

Fade to Black, Old Sport: How Hip Hop Amplifies Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby

When I heard of people flocking to recreate “Gatsby Dress” costumes for Halloween 2013, I couldn’t help but ponder the seemingly-perpetual cultural allure of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, particularly its latest cinematic incarnation in spectacular Baz Luhrmann-style. More than a little of the momentum of the recent revival, however, had everything to do with the film’s soundtrack–executive produced by Jay-Z (who also executive produced the film)–that drew heavily on hip-hop. This sonic move was not without controversy, however, sparking intense debate when the film was released in May 2013. Take this line from Vice Magazine’s UK music blog Noisey (from a post snarkily entitled “Who Let The Great Gatsby Soundtrack Happen?”) that describes Kanye West and Jay-Z’s Watch the Throne album, from which many of the film’s songs are taken, as “a record that couldn’t be further removed from West Egg than a pauper trying to gain access to a Gatsby soiree.” This statement reveals more about this particular listener than it does about either the record or the film, which are intimately connected through the labor of Jay-Z and what I theorize here as a “sonic hip hop cosmopolitanism.”

I’ll admit that when I was first hip to The Great Gatsby my junior year of high school, I thought it was boring and couldn’t stand Tom or Daisy Buchanan or their rich white folk problems. I rooted for Jay Gatsby but couldn’t for the life of me understand why he was so sprung over Daisy, who wanted her daughter to be a “beautiful little fool” (17). But as I got older, I found myself returning to the novel time and time again, coming back to Gatsby like a forlorn lover and reconsidering what Jay Gatsby’s character represents: unrequited love, American idealism, (capitalistic) hustle, and (white) masculine performance. However, I’ve always been part of the camp that secretly hoped Gatsby was a black man passing for white, yearning for a life – and a woman – out of his grasp no matter how much “new money” he acquired.

It was not until Baz Luhrmann’s film adaptation of Gatsby that I realized how hip (hop) Gatsby really could be.

Luhrmann’s modernization of classic literary texts is not new; Romeo + Juliet (1996) got me through high school readings of Shakespeare’s play in ways Sparknotes could not. While Shakespeare’s words remained intact, the scenery and aura of the play burst to life on the big screen. Luhrmann uses in that film sonic cues of contemporary (youth) popular culture to make Shakespeare’s characters relatable. Verona is a hip, urban hub of violence that vibrates to grunge and pop artists such as Garbage, Everclear, and Quindon Tarver instead of mandolins and harps. The grittiness of grunge rock signifies the grittiness of Verona street life while Quindon Tarver’s angelic voice signifies the innocence and vulnerability of (first) love.

But Luhrmann’s Gatsby takes it up a notch, looking to hip hop culture as a bridge between the roar of the 1920s and the noise of the present. Aside from the literal presence of hip hop sound – mostly snippets from Jay-Z and West’s Watch the Throne – the materiality of hip hop sound also serves to update the Gatsby narrative. Consider how Gatsby’s parties are loud and bass-filled with a live jazz band. The loudness of the party and “surround sound” stereo sound of the film amplifies the vibrancy of the Jazz era while drawing in the audience with a contemporary interpretation of live parties seen and heard in contemporary hip hop culture. “The question for me in approaching Gatsby was how to elicit from our audience the same level of excitement and pop cultural immediacy toward the world that Fitzgerald did for his audience?” Luhrmann told Rolling Stone. “And in our age, the energy of jazz is caught in the energy of hip-hop.”

.

The film itself is stunning: vividly colored with panoramas and ground shots of New York City, Luhrmann’s film draws in an audience possibly unfamiliar with Fitzgerald’s novel. The film utilizes the more traditional jazz aesthetic that captures the novel’s initial element, but invokes hip hop to span a generational divide and update the (black) cool factor of the film. Indeed, both jazz and hip hop best signify black cool and its commodification into mainstream white America. For example, Norman Mailer’s discussion of the white hipster and Jazz aficionado as a “white Negro” is also tantalizingly useful in thinking of Gatsby as a black man passing for white. His affinity for Jazz and throwing jazzy parties incites the probability of Gatsby’s racial and social background. The film uses sound to create a hybrid of timeless black cool, while highlighting the presence of African Americans’ contributions to American culture. Hip hop’s birthplace and the portal for many immigrants into America, New York is arguably America’s most mythological city, grounded in both white and African American culture memory as such. Jay-Z’s own mythic rise to fame, wealth, and power in New York City–exemplified in some lines from 2009’s “Empire State of Mind,” “Yeah I’m out that Brooklyn, now I’m down in TriBeCa/ Right next to De Niro, but I’ll be hood forever/ I’m the new Sinatra, and since I made it here/I can make it anywhere, yeah, they love me everywhere”– grounds the film’s rags-to-riches mystique.

In addition to such extradiegetic associations, the film’s soundscape itself enthralls, with brassy, lively instrumented notes of jazz – which carried the sonic narrative of the 1920s – sounds of the hustle and bustle of urban spaces, particularly New York City, and hip hop. The film’s soundscape presents a hybrid of sonic black identities – jazz and hip hop – and uses their blended aesthetics to speak to the continued framework of black popular culture as a gauge of Americanism. In other words, the marginalized perspective is used to decide whether or not something is authentically American or not.

Jay-Z performs at Obama Pre-Election Rally 2012 in

Columbus, Ohio, w/ Bruce Springsteen, Image by Flickr User Becker1999

Hip hop aesthetics bridge old New York with the current New York as a foundation of Americanness. Gatsby bridges the old adage of New York as a space of opportunity with the familiar New York adage that Harlem-born and Mt.-Vernon-raised P. Diddy drops in Jermaine Dupri’s “Welcome to Atlanta,” “if you can make it here, you can make it anywhere,”a call back to Sinatra’s “New York, New York” that is also echoed by Jay-Z that forms a foundational trope of the film and the novel. A particular striking example of the merging of these adages is a scene in the novel where Nick and Gatsby are on their way to the city. They pass a car with black passengers and a white chauffeur:

As we crossed Blackwell’s Island a limousine passed us, driven by a white chauffeur in which sat three modish negroes, two bucks and a girl. I laughed aloud as the yolks of their eyeballs rolled toward us in haughty rivalry.

“Anything can happen now that we’ve slid over this bridge,” I thought; “Anything at all” (69).

While the novel does not describe a sonic accompaniment to Carraway’s observation of the black folks in the limousine, there is an inherent understanding of the “modish” fashion of the black folks as jazzy, as cool. In the film, there is an audible sound associated with the black folks. They are sipping champagne and listening to Watch the Throne. Although visibly symbolic of the 1920s – dressed in zoot suits and flapper dresses – the aural blackness associated with the scene suggests a merger of jazz and hip hop cool and cosmopolitanism.

Still from The Great Gatsby (2013)

In order to understand how hip hop updates the struggle for realness, entitlement, and respectability in the Gatsby film, it is important to return to the major sonic influence of the literal hip hop sound in the film: Jay-Z and Watch the Throne. Jay-Z’s work on the album raises questions of how hip hop culture impacts not only the American dream but the aspirations of mogul-dom seen and heard in the film and novel. Christopher Holmes Smith’s discussion of hip hop moguls in Social Text (Winter 2003) is particularly useful in teasing out the implications behind the hip hop mogul and such figures’ social-cultural responsibility to their respective communities. Holmes Smith argues:

The hip-hop mogul bears the stamp of American tradition, since the figure is typically male, entrepreneurial, and prestigious both in cultural influence and wealth. The hip-hop mogul is an icon, therefore, of mainstream power and consequently occupies a position of inclusion within many of the nation’s elite social networks and cosmopolitan cultural formations (69).

Jay-Z’s status as a hip hop mogul – serving both as a creative talent and corporate backer – lends credence to thinking about hip hop as a space of entitlement and a site of struggle to attain that entitlement. It is from this perspective that I think of Gatsby as a hip hop figure/mogul: his working class background, hyper-performance of white privilege, materialistic pursuit of wealth for visibility, and desperate need for approval as “authentic.” To borrow from rapper Drake, Gatsby “just wanna be successful.”

Mark Anthony Neal’s discussion of Jay-Z as a hip hop cosmopolitan figure in Looking for Leroy (2013) further enables an understanding of how Jay-Z lends his (sonic) hip hop cosmopolitanism to sonically navigate between hip hop’s working class aesthetics and his own sense of entitlement because of the way he mobilized those working class experiences to become wealthy. While the film does have performances by artists who are not considered hip hop – i.e. Lana Del Rey, Jack White, and Florence+the Machine – Jay-Z’s use of his own raps, including tracks from the Kanye West collaboration Watch the Throne suggests a “sonic hip hop cosmopolitanism” complements any sense of the film as a case study of white entitlement. Tracks like “100$ bill,” “No Church in the Wild,” and “Who Can Stop Me” both prop up and tear down Luhrmann’s visual rendition of Fitzgerald’s critique of the uppercrust of America as corruptibly entitled.

.

Baz Luhrmann’s adaptation of The Great Gatsby is an intriguing and useful tool through which to analyze the (in)consistencies of race and cultural authenticity in the United States. Both jazz and hip hop exist in the interstitial spaces that lie between black cultural expression and white entitlement to those expressions. Luhrmann uses hip hop’s sonic and cultural aesthetics to pump up the capitalistic and all-American narrative of “pull yourself up by the bootstraps” narrative in Gatsby by also declaring, “get yours by any means necessary.”

—

Featured Image adapted from Flickr User kata rokkar

—

Regina Bradley recently completed her PhD at Florida State University in African American Literature. Her dissertation is titled “Race to Post: White Hegemonic Capitalism and Black Empowerment in 21st Century Black Popular Culture and Literature.” She is a regular writer for Sounding Out!

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“‘I’m on my New York s**t’: Jean Grae’s Sonic Claims on the City”— Liana Silva

“I Like the Way You Rhyme, Boy: Hip Hop Sensibility and Racial Trauma in Django Unchained“– Regina Bradley

“The Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show and the Soundtrack of Desire“— Marcia Dawkins

Recent Comments