A Conversation With Themselves: On Clayton Cubitt’s Hysterical Literature

Welcome to our second installment of Hysterical Sound. Last week I discussed silence and hysteria in relation to Sam Taylor-Johnson’s silent film Hysteria, suggesting that the hysteric’s vocalizations go unheard because we have tuned them out. In upcoming weeks Veronica Fitzpatrick will explore how the soundtrack of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre can be considered hysterical in its rejection of language and meaning and John Corbett, Terri Kapsalis and Danny Thompson share an excerpt from their performance of The Hysterical Alphabet.

Welcome to our second installment of Hysterical Sound. Last week I discussed silence and hysteria in relation to Sam Taylor-Johnson’s silent film Hysteria, suggesting that the hysteric’s vocalizations go unheard because we have tuned them out. In upcoming weeks Veronica Fitzpatrick will explore how the soundtrack of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre can be considered hysterical in its rejection of language and meaning and John Corbett, Terri Kapsalis and Danny Thompson share an excerpt from their performance of The Hysterical Alphabet.

Today, Gordon Sullivan, considers the video art series Hysterical Literature in relation to a long history of women’s vocalizations serving as aural fetishes for the pleasure of male listeners. In doing so he troubles the dichotomies raised by the project, dichotomies between masculine visual pleasure and feminine aurality, between language and bliss.

— Guest Editor Karly-Lynne Scott

—

Each video in filmmaker and photographer Clayton Cubitt’s Hysterical Literature series (2012-) – which consists of 11 “sessions” so far – appears deceptively simple. We see a black and white frame with a clothed woman seated at a table, visible from the sternum up, holding a book of her choosing. She announces her name and the title of the book before beginning to read. While reading, the subject generally begins to stumble, the speeding of reading slowing down or speeding up, changes in pitch and emphasis growing more pronounced. Eventually, she is able to read no more and gives in to sighs, groans, or silent, eye-closing paroxysms. When she returns to herself, she announces again her name and the title of the book before the “session” ends.

Despite the consistency of the concept, the 11 “sessions” have been viewed a combined 45 million times, and perhaps much of the appeal of the series is in what it doesn’t show. What we do not see – and indeed do not hear – is the “assistant” beneath the table with an Hitachi Magic Wand physically stimulating the subject. What might have been errors or difficulties in the reading are retroactively understood as evidence of the difficulty of “performing” under the attention of the vibrator.

According to Cubitt, the series’ title and conceit nod at the Victorian-era propensity for naming “unruly” female behavior as “hysterical,” where the cure was often the application of a vibrating device to produce “release.” Female sexuality is therefore the absent center of Hysterical Literature – it is there, but can be disavowed (at least visually), a trend that places it firmly in a culture that has an ambiguous relationship to female pleasure and its sounds.

As John Corbett and Terri Kapsalis note in “Aural Pleasure: The Female Orgasm in Popular Sound,” the sounds of female pleasure are “more viable, less prohibited, and therefore more publically available form of representation than, for instance, the less ambiguous, more easily recognized money shot” that characterizes “hard core” pornography (104). Certainly Hysterical Literature’s home on YouTube would seem to confirm Corbett and Kapsalis’ claim that sounds of female pleasure “occur in places…that would otherwise ban visual pornography” (104).

Indeed, the question of pornography looms over Hysterical Literature, as Cubitt seeks to push on YouTube’s “Community Guidelines” by exhibiting female pleasure sonically (See also Joshua Hudelson for a discussion of sexual fetish and the ASMR community on Youtube). Here the sound of the subject’s voice echoes Linda Williams’s description in Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and “The Frenzy of the Visible,” where the female voice “may stand as the most prominent signifier of female pleasure” that can stand in for the pleasure we are denied access to visually (123). In this way, the sound of female pleasure is, as Corbett and Kapsalis suggest, always evidentiary (104). For them, a woman’s pleasure may/must be corroborated by her sounds (For an alternative view of gender and sound as it relates to women, see Robin James’ “Gendered Voice and Social Harmony”).

This pleasure calls to mind Roland Barthes, who saw the possibility of bliss and representation as fundamentally incompatible. For Barthes, the “grain” of the voice is a bodily phenomenon, not one of language and signification. For him, “the cinema capture[s] the sound of speech close up…and make[s] us here in their materiality, their sensuality, the breath, the gutturals, the fleshiness of the lips, a whole presence of the human muzzle” (67). This “materiality” has a single purpose: bliss. This bliss doesn’t reside in language, with its representational aims, but in those aspects of the voice that are not ruled the signifier/signified dynamic.

What draws me to these discussions – and their relation to Hysterical Literature – is the almost overwhelming insistence on dichotomy. The visual “evidence” of hard core pornography is juxtaposed to the aural “evidence” of female pleasure. Male pleasure (on the side of the visible) is opposed to female pleasure (on the side of the invisible). Representation is incompatible with “bliss.”

This logic is not confined to discussions of sound, but is echoed in some of the writing on Hysterical Literature as well. In her profile (which included her own “session”), dancer and writer Toni Bentley argues that the series “juxtaposes the realm of words literally atop the realm of the erotic.” In her view, this immediately becomes a conflict: “Who would win the inevitable war? Upper body or lower? Logic or lust? Prefrontal cortex or hypothalamus?” Though her list of oppositions may seem idiosyncratic, she still insists on division before suggesting that what might emerge instead is that they “meld together.”

Bentley is not alone in understanding the videos this way, as other subjects find a clean break between “I am reading” and “I am orgasming” that would suggest a strict dichotomy between, as Barthes would put it, representation and bliss. For Bentley, this is a “literate, and literal, clitoral monologue that renders the Vagina Monologues merely aspirational.” I’m not sure that “monologue” captures the depth of what is happening in each Hysterical Literature session. Cubitt’s goal is to reveal something about his subjects, to use “distraction” as a means for revelation that ultimately removes him from the scene. Indeed, the participation of the vibrator-wielding “assistant” and Cubitt’s status as filmmaker argue that instead of a monologue, the series facilitates what Cubitt calls “a conversation with themselves.”

Though Cubitt and his subjects seek to maintain the division between the subject and her distraction, the series is far more interesting than that dichotomy would suggest. Hysterical Literature is interesting not because it juxtaposes “reading” and “orgasm,” but rather because of the rigor with which it is willing to dwell in between these two (apparently) opposed states. There is no cut, no switch in which a subject goes from reading to not-reading. Every video begins and ends the same way – we open on a woman telling us her name and her book, and end the same way, orgasm over with. In between, however, we have a combination of the book chosen by the subject and her augmented reading. Rather than the sighs and groans that supposedly evidence the subject’s pleasure, the more interesting elements are the sounds of the book transformed. The cadence that slows down, speeds up, gets lost, and must repeat. The drawn out vowels that teeter between a gracefully pronounced word and the abyss of unintelligibility. That the “struggle” will end in orgasms and the loss of speech is less significant than the attempt to maintain a voice in the face of what cannot be denied.

If we grant a gulf between “representation” and “bliss,” Hysterical Literature suggests that such a gulf is a productive place to be.

—

Gordon Sullivan is a PhD candidate at the University of Pittsburgh, currently writing a dissertation on questions of sensation and the political in exploitation films.

—

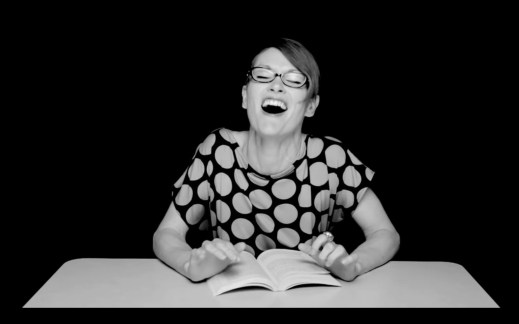

Featured image taken from “Hysterical Literature: Session Four: Stormy“.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Echo and the Chorus of Female Machines — AO Roberts

This Is How You Listen: Reading Critically Junot Díaz’s Audiobook — Liana M. Silva

Standing Up, For Jose — Mandie O’Connell

Music Meant to Make You Move: Considering the Aural Kinesthetic

In the two weeks prior to my drafting this piece, the world lost Adam “MCA” Yauch, Robin Gibb, Donna Summer, and Chuck Brown. In their wake they leave a profound legacy of music, yes, but of dance music particularly. MCA declared your right to party while demonstrating that white MCs aren’t always gimmicks. The BeeGees gave you a new strut courtesy of the bounce-funky soundtrack to Saturday Night Fever. The goddess Donna Summer seduced your ears with her orgasmic whispers, then pumped up the pulsating synthetic beats that brought the discotech from its urban centers directly to you. And go-go’s blaze, though not as far-reaching as disco’s, grew out of Chuck Brown’s musical sensibility, and burned deep in the hearts of Chocolate City natives. For all of these artists, moving to the music isn’t merely a possibility or inclination, but a deeply irresistible impulse. Altogether, these artists brought music that not only called out to people to dance, but if you didn’t dance you missed something essential: the inextricable ties between music and movement. One acts as a key that opens up a dimension to understanding the other.

Seeing people dance to a live go-go band taught me how to appreciate their music. When I finally heard go-go for the first time at a club in 1995, it challenged my musical sensibilities, which were more attuned to smooth R&B and jazzy Hip Hop. By then, go-go music seemed so fast, and coupled with the multiplicity of drums that I didn’t know how to get inside of the groove. In the midst of the bubbling fervor I stood noticeably still as the young woman next to me ripped the shirt off her sweaty body and whipped it above her head (like a flag at carnival), never once missing a beat in her frantic jumping and pumping to the live drums while wearing only her bra and a pair of jeans. The dancing bodies of the whole club fueled my understanding, and by extension appreciation, of what go-go does. Without them, I would have missed out on something deeper.

I am drawing your attention both to music meant to make you dance and dancing that is necessarily done to music—i.e the arena of social dance. Julie Malnig, in Ballroom, Boogie, Shimmy Sham, Shake: A Social & Popular Dance Reader, defines “social dancing” by “a sense of community often derive[d] less from preexisting groups brought together by shared social and cultural interests than from a community created as a result of the dancing” (4, emphasis in original). That might include social dances that correspond to particular songs, or called and standardized steps, like the twist or the electric slide. My focus is more broadly on a visceral, embodied, kinesthetic response to dance music in a particular social space, which is not explicitly directed by the lyrics or a set of moves but by the feel of a song as a whole. In the Hip Hop social dances I write about, rather than a finite set of moves there are infinite possibilities for improvisational play within a particular style (like b-boying or popping) that the music draws out of the dancer. As David F. García states in his piece on mambo titled “Embodying Music/Disciplining Dance: The Mambo Body in Havana and New York City,” “the embodied experience of sound and movement [are] merged through the body” (172).

Break Dancing en Costa Rica, 2009 by Flickr User Néstor Baltodano, under Creative Commons License 2.0

I have come to name the frame for analyzing the simultaneity of social dance and music (and sound broadly) as aural-kinesthetics. While these words capture sound and movement separately, together I am looking to engage more than just the sensory response of moving to what one hears. The term develops out of works by music scholars like Kyra Gaunt (The Games Black Girls Play: Learning the Ropes From Double Dutch to Hip Hop), Kodwo Eshun (More Brilliant Than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction), and Kai Fikentscher (“You Better Work!”: Underground Dance Music in New York City), who shift our orientation to music and rhythm by drawing on our kinesthetic responses to it. Aural kinesthetics recognize that social dance practices are kinesthetic forms within the all-encompassing aurality of an environment. I use spatial terms to acknowledge sound’s omni-directionalality, coming at you from all sides and helping to actually produce the social dance place. In other words, the aural kinesthetic is also a kind of spatial practice (along the lines of Henri Lefebvre’s The Production of Space). For example, consider how a bomba dancer orchestrates the primary bomba drummer’s rhythms within the rhythmic arena created by the second and tertiary drummers; or how loud music in street dance performances fills the immediate surroundings and bleeds out into other areas, attesting to their capacity to claim public spaces (the volume has volume). Music in particular plays a fundamental role in establishing the conceptual performance arena that ultimately makes the physical space functional for certain dance practices.

Despite the fact that social dances necessarily have a musical component, dance is typically overdetermined by the visual, which in Western cultures we are better equipped to address. The sound and feel of dance experiences are often overridden by the spectacle of dancing, which the following clip demonstrates. In this clip showcasing the final battle from the 2007 Freestyle Sessions in Los Angeles, the spectacle of these amazing dancers distracts you from the actual social dynamics of their battle, of which music is central.

.

The exchange between dancers is truncated, spliced together for dramatic effect. You focus on the center of the cypher, lost in the visual thrill of it all. The song they were actually dancing to is replaced by another that, though danceable, prevents us from appreciating a particular song’s nuances as well as the crowd and emcee’s involvement in the event. Overdubbing songs that you do not have clearance for is in compliance with copyright laws that force the video’s producers to instead play songs to which they have legal access, in sacrifice of aural-kinesthetic experiences the videos attempt to capture. Yet even in cases of the below clip where we hear the original song, the recording cannot capture the quality of the force of the music that is loud enough to feel throughout your entire body, thereby promoting a shared sensorial experience in the room. Whether one is recording with a camera or in writing, capturing the aural-kinesthetic can be tricky.

2009 Dutch B-Boy Championships Semi-Finals between Hustle Kids and Rugged Solutions

For me, the aural-kinesthetic is useful insofar as it opens up creative space for me in writing the simultaneity of sound and movement. Scholars like Mary Fogarty (Dance to the Drummer’s Beat: Competing Tastes in International B-Boy/B-Girl Culture) have approached the topic by distinguishing between notions of musical taste and musical competency in clarifying the contours of b-boying’s dance-music relationship. In my own writing, I’ve tended toward storytelling and descriptive analyses. In contrast, considerations such as those of Roland Barthes’ “The Grain of the Voice” (in Image, Music, Text) propose to expand the language on (vocal) music in general by shifting the object of analysis to create new ways of writing music, which we can extend to writing social dance.

So what is a productive approach for writing the aural-kinesthetic? I’m not prescribing a method, but I do want to consider the possibilities of shifting the focus of analysis in such a way that it allows for the simultaneity of music and movement. For example, there may be value in examining a gesture repeatedly made to a particular part of a song to understand what that song is doing; or examining the physical layout of a room and how that space gets used through the song that fills it. Perhaps coming at social dance indirectly and on multiple fronts makes for a richer depiction.

For now, let’s take advantage of this digital space and collectively consider our options. Here’s a task I hope you might take up: post a link to a song or a video clip that makes you move. Describe some quality of your visceral response to the song and place your thoughts in the comments section below. Include the multiple fronts that help you to articulate your experience. While music and dance have the capacity to “speak” in ways that verbal language cannot always reach, my hope is that a range of possibilities might get us there. or at least much closer.

—

Dr. Imani Kai Johnson is a Ford Dissertation Fellow, who has just completed a three year postdoctoral fellowship at NYU’s Performance Studies Department. She received her PhD in American Studies & Ethnicity at the University of Southern California in 2009, where she wrote a dissertation titled,”Dark Matter in B-Boying Cyphers: Race and Global Connection in Hip Hop,” which considers the cultural and performative dimensions of Hip Hop dance as a global phenomenon through cyphers (dance circles), and the invisible forces of the collaborative ritual. Dr. Johnson is currently completing a manuscript based on her dissertation.

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- SO! Reads: Alexis McGee’s From Blues To Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics

- SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

- Impaulsive: Bro-casting Trump, Part I

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments