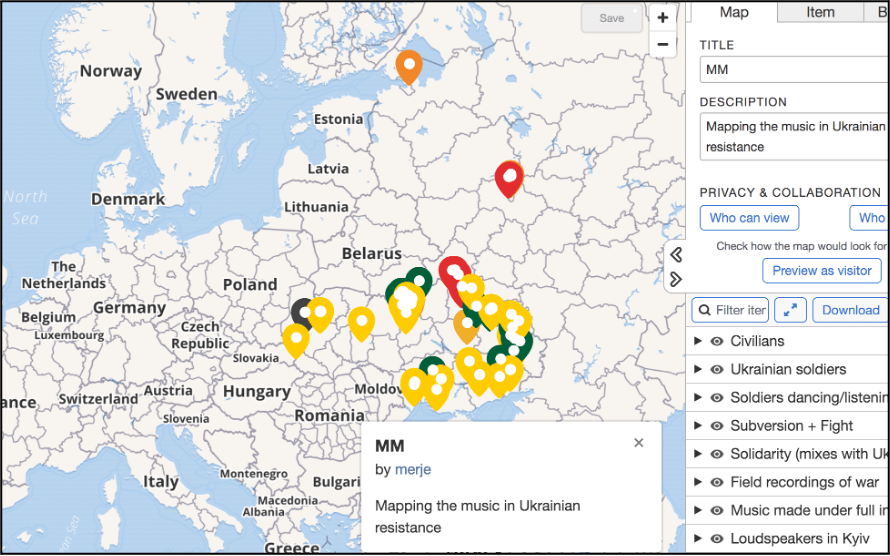

SO! Amplifies: An Interactive Map of Music as Ukrainian Resistance to the 2022 Russian Invasion

https://maphub.net/merje/mm

SO! Amplifies. . .a highly-curated, rolling mini-post series by which we editors hip you to cultural makers and organizations doing work we really really dig. You’re welcome!

—

BONUS POST: Directly following Merje’s introduction to her music mapping project, SO! has also published is her analysis of the observational research she conducted during the first 55 days of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, drawing from the collection of videographic material from online sources she embedded on this public interactive map. To go directly to that post, click here.

As an Estonian national, I have a regional interest in the relationship between music and cultural identity in Eastern Europe. Popular music has been foundational in building and sustaining Estonian national identity, through the Song Festival tradition which started in 1869, and the Singing Revolution at the end of the 1980s. In the Baltic states, Poland and Ukraine, there are similarities in how music has facilitated resistance to an oppressive regime or invasion.

While other cultural forms can articulate and show off shared values, only music can offer the immediate experience of collective identity (Frith 2007, 264). Looking into the sensitive representation of music in conflict, therefore, is about exercising hapticity with the precarity and suffering in the videos, and ultimately a work of not only academic, but affective labour.

The map format helps visualise the video evidence as it continues to appear in different parts of Ukraine. For accurate analysis, understanding the context, region, and the phase of war in which a musical event originates, is vital. In different parts of the country on the same date, one city can embody a collective feeling of resistance, while the other grief. The map is useful in analysing regional differences in the types of songs performed, and in ‘placing’ the international cases of solidarity. I decided to map the solidarity mixes that directly engage with the musical footage from Ukraine, and to exclude the high number of global fundraising concerts. All map entries depict in some way the role of music in Ukrainian resistance.

The map function is made redundant in posts where the location should not be disclosed for safety reasons, such as this video of soldier Yuriy Gorodetsky performing ‘How Can’t I Love You, My Kyiv’ in a military camp. Additionally, I decided not to embed posts that could inform the Russian military of civilian and humanitarian targets, for example a video from Lviv showing the Philharmonic concert space being used for humanitarian storage.

The focus has been on mapping songs and music, rather than the wider soundscape of war, although sounds such as air raid sirens do appear in some videos. The map includes sections on recorded music, such as this wartime ska track by Mandry, field recordings, and ways in which music has been used in online warfare. Most map entries fall under the civilian resistance category, exploring the following questions:

- What kind of music appears in this resistance? In terms of genre, is it folk, rock, hip hop, or national patriotic song? Is it Ukrainian or ‘Western’? How do the different examples embody national feeling and safeguarding of a culture?

- What is the power of these musical moments, for the artists, for Ukrainians, and for the world? What can music achieve in a conflict environment, and how does it evoke moments of solidarity?

- How does the music reflect the different phases and emotions of the war, from mobilisation, resistance, support, contemplation, to grief?

Similar research questions have been posed by Arve Hansen et al. in A War of Songs (2019) about the 2013-14 Euromaidan protests, in which music carried much of the revolutionary feeling. Adriana Helbig wrote about the Orange Revolution of 2004-05 in Hip Hop Ukraine: Music, Race, and African Migration when the Internet played a huge role in circulating political messages through music, especially as Ukraine’s media was controlled by president Yanukovich (2014). Maria Sonevytsky’s Wild Music (2019) looks at both revolutions and the vernacular Ukrainian discourses of ‘wildness’ as they manifested in popular music during this politically volatile decade.

When looking at Ukraine, we are studying a repeatedly colonised region, where, as part of the former Russian Empire, serfdom was abolished in 1861. Ethnographic research and promotion of a national culture in the decades that followed led to a brief window of independence for Ukraine in 1917, only to be occupied and incorporated into the Soviet Union as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in the same year. Unlike Poland and the Baltic states, Ukraine was not independent between the two world wars, which adds depth to Soviet propaganda that permeated the region throughout the 20th century – important context to consider when analysing its struggle for autonomy.

Drawing from Parkes, the relationships of domination and subordination are particularly marked and articulated through music in colonised groups (Parkes 1994). Often, Ukraine is portrayed as a country of two opposing regions: the pro-European West and the pro-Russian East. While there have been two sides opposed to each other since the 2014 Crimean occupation, the linguistic, ethnic, historical and religious divisions in Ukraine cannot neatly fit into this East-West dichotomy. In addition to complicated ethnic boundaries that define and maintain the region’s cultural identities, Ukraine is dealing with a post-colonial struggle to protect its independence from imperialist Russia.

The ‘places’ constructed through Ukrainian music embody these complex issues, notions of difference and social boundaries – the very reason why music is socially meaningful: it provides means by which people recognise identities, places and the boundaries which separate them (Stokes 1994). In a war situation, beyond political and social alliances, we are also looking at music as survival (Stokes 2020).

—

Merje Laiapea is a curator, artistic programmer and writer working across sound, music and film. She is completing her Master’s in Global Creative and Cultural Industries in the Music Department at SOAS, University of London. Within the broad realm of music and cultural identity, her research interests include the expressive power of the sound-image relationship, forms of frequency, and multimodal approaches to research itself. She assists with event production and community engagement at SOAS Concert Series and works as Submissions Advisor for the 2022 Film Africa festival. Merje also broadcasts the occasional radio show and DJ mix. To find out more about Merje’s motivation behind the project, click here to read an interview by the University of London.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig this:

Mapping the Music in Ukraine’s Resistance to the 2022 Russian Invasion–Merje Laiapea

SO! Amplifies: Wu Tsang’s Anthem (2021)—Freddie Cruz Nowell

SO! Amplifies: Marginalized Sound—Radio for All–J. Diaz

SO! Amplifies: Die Jim Crow Record Label

SO! Amplifies: Cities and Memory–Stuart Fowkes

‘No Place Like Home’: Dissonance and Displacement in Gimlet Media’s Fiction Podcast “Homecoming”

In honor of International Podcast Day on 30 September, Sounding Out! brings you Pod-Tember (and Pod-Tober too, actually, now that we’re bi-weekly) a series of posts exploring different facets of the audio art of the podcast, which we have been putting into those earbuds since 2011. Enjoy! –JS

Last month, Gimlet media released the audio-feature length podcast The Final Chapters of Richard Brown Winters, starring Catherine Keener, Parker Posey, Bobby Cannavale, Sam Waterston, and Darrell Britt-Gibson, many of the same cast members from their critically-acclaimed podcast Homecoming, and also co-written by Eli Horowitz, Homecoming’s co-creator and co-showrunner. Along with the podcast’s famous move to Amazon TV in 2017, Gimlet’s podcast reunion prompted me to re-listen to Homecoming, trying to figure out how its signature use of audio—characterized by Horowitz as “letting the scenes and the conversation create the action instead of describing the action”—propelled the series to its success in the first place.

Homecoming concerns characters connected with afictional military rehabilitation facility in Tampa, Florida, that ostensibly prepares soldiers suffering PTSD for a return for civilian life. The soldiers are subjects of an experimental drug treatment program devised by the US Defence Department-affiliated Geist Group to erase traumatic memories of combat and eliminate resistance to re-deployment. Set in a specifically post-9/11 political milieu, the series plays out in the implied real world context of multiple and on-going US foreign military interventions. Homecoming foregrounds the sonic/auditory modes associated with war–in particular covert electronic surveillance–working to create an atmosphere infused with suspicion, secrecy and deception. In Homecoming’s dissonant sonic/narrative environment ‘home’ is as perilous as the frontline.

Dissonance and displacement inherent in the auditory experience are overarching themes in Homecoming and manifest in an atmosphere of uncertainty regarding temporality, memory, identity and ideas of “home” itself. The sonic world of Homecoming is infused with a sense of discord—recorded audio is subject to manipulation and misinterpretation—and the voice is a site of multiplicities that destabilise concepts of identity and reality. The podcast’s pervasive “out of tune-ness” produces a heightened state of listening – a hypervigilance – both in Homecoming’s characters as they attempt to decipher multiple conflicting aural “intel,” and in the podcast’s audience as we do likewise. It is this dissonance that compels Homecoming’s listeners to prick up our ears and listen more keenly.

GETTING “SITUATED”

The series’ distinctive non-linear, explicitly sound technology-mediated storytelling style takes the form of an “enigmatic collage” of sound artifacts: recorded therapy sessions between Heidi Bergman (Catherine Keener), a case worker/counsellor at the Homecoming facility, and Walter Cruz (Oscar Isaac), a soldier whose recovery she is monitoring; fraught phone conversations between Heidi and the heavily-compromised senior management at Geist; covert surveillance tapes of interaction at the facility between Walter and fellow soldier, Schrier (Babak Tafti), and between Walter and Heidi; and a series of voice messages ostensibly left by Walter on a mobile phone he has given to his mother.

In “Mandatory,” Homecoming’s opening episode, in a fragment of a recorded counselling session between Heidi and her client Walter Cruz, the second in a succession of these fragments that play out over Series One, Heidi tells Walter that her objective is to help to get him “situated” now that he’s back. Through abrupt temporal shifts between the recorded past and the present, the series reveals that this objective was always already thwarted and that Walter’s “situation” in the present is unfixed, unknown and potentially unknowable. Homecoming’s specific atmospheric aural/narrative mode conveys an unsettling sense of fractured selves in an ever-more fractured sonic landscape. Walter functions in this landscape as a reflexive site of multiple sonic presences. At once static and mutable, fixed and shifting he “exists” and is transmitted across a range of sound technologies. Though captured by these recordings, at the same time he evades capture by those seeking him out.

In Homecoming, Walter’s presence is constructed through absence, which positions him as a kind of acousmêtre, described by Michel Chion in The Voice in Cinema as “one who is not-yet-seen but is liable to appear at any moment” (21). Chion has described how “an entire story… can hang on the epiphany of the acousmêtre”…the quest to bring the acousmêtre into the light” (23). In considering the podcast form, being “seen” can be understood as the conveying of presence, that is, the technical and affective means through which a character is felt or experienced. In Homecoming’s specific reflexive use of sound technology to construct Walter as present yet “unseen,” Walter is everywhere and nowhere, always there but at the same time always not there. The series finds a means of achieving what Chion has suggested is unachievable in radio and, by inference, in the podcast – “playing with” presence, partial presence and absence (21). This affective ‘play with presence’ works too to challenge concepts of the ‘disembodied’ voice and speaks to Christine Ehrick’s call in “Gendered Soundscapes” for a more nuanced exploration of the voice/body relationship. As Ehrick puts it – “if the voice is not the body, what is it?”.

In “Mandatory,” Walter is specific about his willingness to adhere to the conditions of his treatment: “I want to be in compliance,” he tells Heidi. Yet Walter’s multiple itinerant sonic selves seem to resist compliance. Though his presence in Homecoming is constructed through a series of seemingly fixed recordings that might suggest change is precluded, Walter is, paradoxically, a site of radical change. In his technology-contingent presence in the series, Walter, having removed himself from circulation, becomes a ‘soldier-body’ in revolt, resisting placement, compliance and commodification. Goldberg and Willse have identified the “soldier-body” as a “temporary” conduit of “the networks of technoscience and capital [that allows] these networks to adapt and survive” in “Losses and Returns: the Soldier in Trauma” (266-267). It is an argument that manifests in Homecoming in Geist’s covert pharmacological strategies to remediate the psychological fragmentation of war trauma in order to render the ‘soldier-body’ utterly compliant and redeployable. Walter’s perpetually withheld presence revokes his soldier-body’s viability as bio-capital and is framed in the series as an existential threat to the military-industrial complex.

“IF WE’RE NOT IN FLORIDA, WHERE ARE WE?”

Ideas of place and presence, particularly in relation to the non-compliant soldier-body, are further problematized in Homecoming in the sole interaction we hear between Walter and Schrier, another returned soldier, in yet another mode of voice recording. In Episode 2, “Pineapple,” within an internet-based call, Heidi’s boss Colin plays her a surveillance recording from the Homecoming cafeteria, one of several instances in the series of the multiple-layering of sound technology. We listen in as Walter and Schrier eat the pineapple-based dessert they’ve been served and debate Schrier’s “pineapple-induced” doubts about their actual location. For an agitated Schrier, pineapple is pineapple-no-longer but a repository of a sinister excess of meaning – a sign that “they,” the military, are “really laying it on thick with this Florida shit.” Are they in Florida or not? Schrier demands evidence: “the only reason we think we’re in Florida is because that’s what they told us”. These duplications, both actual (the recording) and suspected (a fake Florida), produce an atmosphere layered with dissonance and uncertainty.

While Shrier’s suspicion of a fake Florida proves unfounded, this other duplication (the surveillance recording) has catastrophic consequences for him. In Episode 6, “Hysterical”, we learn that after being dropped from the Homecoming treatment programme, Schrier was abruptly taken off the medication that was being administered to him without his knowledge (via the pineapple, as it happens). In yet another fraught call with a distressed Heidi, Colin matter-of-factly recounts the disastrous aftermath for Schrier: “he bit off a chunk of his tongue, spit it at an orderly, then he tried to hang himself. They’ve got him in restraints.”

Not only do the Homecoming soldiers bring traces of war home with them – traumatic memories and symptoms of PTSD – but the place to which they return turns out to bear traces of a war zone. The America of Homecoming is a liminal space, an environment that harbours hidden dangers. While ostensibly home turf, America is a space that functions, in an orchestrated clandestine manner, as an outpost of war, or rather, encompassed within what Ben Anderson has identified as the borderlessness of “total war” (169-171). For Schrier, sonic capture within the Homecoming surveillance recordings pre-figures further physical capture. Ultimately, he ends up hospitalised and literally restrained.

“HEY MA, IT’S ME, IT’S WALTER…”

Though carceral, a place of enclosure that gestures toward the enclosure inherent in the idea of “total war,” the sonic space of the recorded voice artifact in Homecoming exists also as a site of resistance. Walter’s presence in Season Two manifests via a series of voicemail messages left on a cell phone he has given to his mother, Gloria (Mercedes Ruehl). In Episode 8, “Cipher,” Colin, masquerading as a lawyer taking a class action against the government on behalf of the soldiers maltreated at the Homecoming Facility (one of several fake identities he assumes), persuades Gloria to hand over this phone. As if also infected with Walter’s restlessness, the audio files of these messages migrate from Gloria’s phone to the Geist Server to Heidi’s laptop before we actually hear them. The messages provide a cartographic trace of Walter’s movements west, then north, then south and provide those tracking him, Colin and Heidi, with the first hard evidence of his possible whereabouts. Or at least they seem to.

Again Homecoming draws attention to technologies of reproduction and their influence in how we “conceptualise the voice and its powers” as Weidman states in her essay on “Voice” in Keywords in Sound (236). Walter’s phone is understood as an extension of his affective presence. When subsequent faked messages are left on the phone—the first constructed by Gloria to throw Walter’s trackers off the scent, the second by Heidi in order to entrap Colin—it is this aura of authenticity, the misplaced faith in the faithfulness of the sound recording that serves to legitimate the fakes. The messages, both real and faked, carry the aura of the original voice but their increasingly uncertain status signals “the ontological plasticity of the voice” that Nick Prior has articulated in “On Vocal Assemblages” (489), how “the voice sounds out in a social space comprised of a whole panoply of discourses, techniques and machines that objectify and posit it as a particular kind of object and information”(495). In this instance simulation is an act of ‘pushback’ against networks of power, against the seemingly-fixed borders of recording technology, it is an act that for Walter effects a kind of escape. He remains ‘un-situated.’ Perhaps the safest place for Walter, the only place like home, is in the ‘no place’ of the digital recordings in which he manifests.

Farokh Soltani describes the podcasting form as “the key transformative development in the history of audio drama” in “Inner Ears and Distant Worlds: Podcast Dramaturgy and the Theatre of the Mind” because of the way it “detaches drama from the economic, institutional and political requirements of the radio broadcast” (189). The vast trove of alternative, ‘unsanctioned’ voices podcasting has made audible can be said to resonate with the discernible hum of difference, the form itself can be understood as inherently dissonant. Its fundamental alterity imbues it with the affective essence of dissonance that Sean Gurd articulates in Dissonance: Auditory Aesthetics in Ancient Greece (2016) as “extra-audible information…[a kind of] roughness, a richer, grainier, less-polished sound” (11). The sense of palpable auditory/affective ‘roughness’ or dissonance permeates Homecoming sonic world, frequently in the foregrounded presence of sonic ‘dirtiness’ but always in its distinctive non-linear assemblage and in its inherent critique of the far-reaching and devastating impacts of war. Homecoming’s audio and structural strategies, shifting both temporally and between sonic modes, demand too that we, the listeners, like Walter and Heidi, are actively and continually engaged in the urgent process of attempting to find our bearings, to get ourselves ‘situated.’

—

Featured Image: “American Redaction,” by Jared Rodriguez / truthout (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

—

Miranda Wilson is a Creative Practice Ph.D. Candidate in Film Studies at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. Her creative and scholarly thesis (Supervisor, Prof. Annie Goldson) interrogates and experiments with the ways in which voice/image positioning in documentary can and might invigorate screen space as a site of common space and counter-space. Her research encompasses strategies of indirect representation, in particular with regard to gender and voice/image relations; ensemble narratives that work to de-centre the protagonist; low/no budget filmmaking methods that democratize the means of production and documentary practice that is as much about interrogating the documentary form as it is about the subject it engages with. The research project seeks to detect and articulate documentary space in which individuals cohere as a citizenry and everyday practices of democracy are enlivened. Miranda also holds a BA Honours (First Class) from the University of Auckland. Her graduate studies have encompassed research into sound and dissonance; sound/image relations; documentary theory and practice; and representations of spatial transgressions in cinema space.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

The Sonic Roots of Surveillance Society: Intimacy, Mobility, and Radio-Kathleen Battles

SO! Podcast #80: Refugee Realities Miniseries—Amanda Patton, Ahmad Frahmand, Melvin Mora Rangel, and Brad Joseph

SO! Podcast #79: Behind the Podcast: deconstructing scenes from AFRI0550, African American Health Activism – Nic John Ramos and Laura Garbes

A Manifesto, or Sounding Out!’s 51st Podcast!!! – Aaron Trammell

Acousmatic Surveillance and Big Data-Robin James

Recent Comments