SO! Amplifies: Ian Rawes and the London Sound Survey

SO! Amplifies. . .a highly-curated, rolling mini-post series by which we editors hip you to cultural makers and organizations doing work we really really dig. You’re welcome!

SO! Amplifies. . .a highly-curated, rolling mini-post series by which we editors hip you to cultural makers and organizations doing work we really really dig. You’re welcome!

.

—

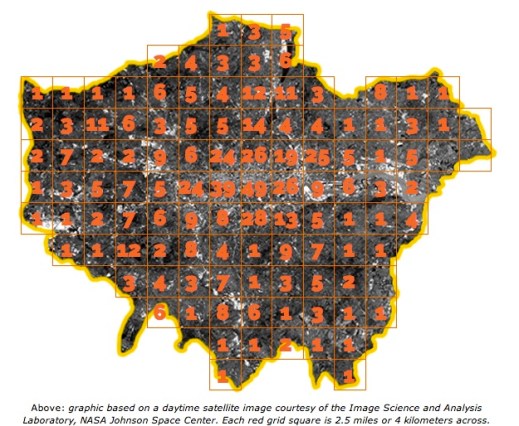

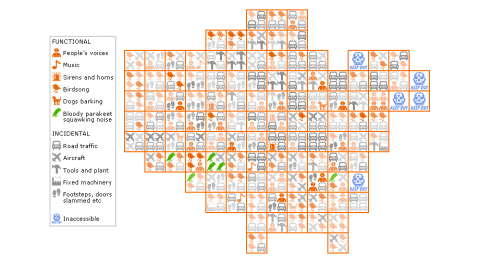

The London Sound Survey website went online in 2009 with a couple of hundred recordings I’d made over the previous year. For a long time I’d wanted to make a website about London but couldn’t think of a good angle. When I got a job as a storeman in the British Library’s sound archive I became interested in field recording. There were the chance discoveries in the crates I hauled around of LPs like Murray Schafer’s The Vancouver Soundscape and the Time of Bells series by the anthropologist Steven Feld. I realised that sound could be the way to know my home city better and to present my experience of it.

Fast forward to last week: It is a warm June afternoon and the marsh is alive with the hum of the Waltham Cross electricity substation. I am a few miles to the northeast of London in the shallow crease of the Lea Valley. It’s a part of the extra-urban mosaic of reservoirs, quarries, industrial brownfield sites, grazing lands, nature reserves and outdoor leisure centres which has been usefully named “Edgelands” by the environmentalist Marion Shoard.

Sounding Out! Podcast #31: Game Audio Notes III: The Nature of Sound in Vessel

This post continues our summer Sound and Pleasure series, as the third and final podcast in a three part series by Leonard J. Paul. What is the connection between sound and enjoyment, and how are pleasing sounds designed? Pleasure is, after all, what brings y’all back to Sounding Out! weekly, is it not?

This post continues our summer Sound and Pleasure series, as the third and final podcast in a three part series by Leonard J. Paul. What is the connection between sound and enjoyment, and how are pleasing sounds designed? Pleasure is, after all, what brings y’all back to Sounding Out! weekly, is it not?

Part of the goal of this series of podcasts has been to reveal the interesting and invisible labor practices which are involved in sound design. In this final entry Leonard J. Paul breaks down his process in designing living sounds for the game Vessel. How does one design empathetic or aggressive sounds? If you need to catch up read Leonard’s last entry where he breaks down the vintage sounds of Retro City Rampage. Also, be sure to be sure to check out last week’s edition where Leonard breaks down his process in designing sound for Sim Cell. But first, listen to this! -AT, Multimedia Editor

–

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD: Game Audio Notes III: The Nature of Sound in Vessel

SUBSCRIBE TO THE SERIES VIA ITUNES

ADD OUR PODCASTS TO YOUR STITCHER FAVORITES PLAYLIST

–

Game Audio Notes III: The Nature of Sound in Vessel

Strange Loop Game’s Vessel is set in an alternate world history where a servant class of liquid automatons (called fluros) has gone out of control. The player explores the world and solves puzzles in an effort to restore order. While working on Vessel, I personally recorded all of the sounds so that I could have full control over the soundscape. I recorded all of the game’s samples with a Zoom H4n portable recorder. My emphasis on real sounds was intended to focus the player’s experience of immersion in the game.

This realistic soundscape was supplemented with a variety of techniques that produced sounds that dynamically responded to the changes in the physics engine. Water and other fluids in the game were difficult to model with both the physics engine and the audio engine (FMOD Designer). Because fluids are fundamentally connected to the game’s physics engine, they takes on a variety of different dynamic forms as players interact with the fluid in different ways. In order to address this Kieran Lord, the audio coder, and I considered factors like the amount of liquid in a collision with anything, the hardness of the surface that it was colliding with, the type of liquid in motion, whether the player is experiencing an extreme form of that sound because it is colliding with their head, and, of course, how fast the liquid is travelling.

Although there was a musical score, I designed the effects to be played without music. Each element of the game, for instance a lava fluro’s (one of the game’s rebellious automatons) footsteps, entailed required layers of sound. The footsteps were composed of water sizzling on a hot pan, a gloopy slap of oatmeal and a wet rag hitting the ground. Finding the correct emotional balance to support the game’s story was fundamental to my work as a sound designer. The game’s sound effects were constantly competing with the adaptive music (which is also contingent on player action) that plays throughout the game, so it was important to provide an informative quality to them. The sound effects inform you about the environment while the music sets the emotional underscore of the gameplay and helps guide you in the puzzles.

Defining the character of the fluros was difficult because I wanted players to have empathy for them. This was important to me because there is often no way to avoid destroying them when solving the game’s puzzles. While recording sounds in the back of an antique shop, I came across a vintage Dick Tracey gun that made a fantastic clanking sound when making a siren sound. Since the gun allowed me to control how quickly the siren rose and fell, it was a great way to produce vocalizations for the fluros. I simply recorded the gun’s siren sound, chopped the recording into smaller pieces, and then played back different segments randomly. The metal clanking gave a mechanical feel and the siren’s tone gave a vocal quality to the resulting sound that was perfect for the fluros. I could make the fluros sound excited by choosing a higher pitch range from the sample grains and inform the player when they approached their goal.

I wanted a fluid-based scream to announce a fluro’s death. I tried screaming underwater, screaming into a glass of water, and a few other things, but nothing worked. Eventually, when recording a rubber ear syringe, I found squeezing the water out quickly lent a real shriek while it spit out the last of the water. Not only did this sound really cut through the din of the gears clanking in the mix, but it also bonded a watery yell with the sense of being crushed and running out of breath.

Vessel’s Lava boss with audio debug output. Used with permission (c) 2014 Strange Loop Games

For the final boss, I tried many combinations of glurpy sounds to signify its lava form. Eventually I recorded a nail in a board being dragged across a large rusty metal sheet. Though it was quite excruciating to listen to, I pitched down the recording and combined it with a pitched down and granulated recording of myself growling into a cup of water. This sound perfectly captured the emotion I wanted to feel when encountering a final boss. Although it can take a long time to arrive at the “obvious” sound, simplicity is often the key.

Anticipation is fundamental to a player’s sense of immersion. It carves a larger space for tension to build, for instance a small crescendo of a creaking sound can develop a tension that builds to a sudden and large impact. A whoosh before a punch lands adds extra weight to the force of the punch. These cues are often naturally present in real-world sounds, such as a rush of air sweeping in before a door slams. A small pause might be included just for added suspense and helps to intensify the effect of the door slamming. Dreading the impact is half of the emotion of a large hit .

Recording inside of a clock tower with my H4n recorder for Vessel. Used with permission by the author.

Recording all of the sounds for Vessel was a large undertaking but since I viewed each recording as a performance, I was able to make the feeling of the world very cohesive. Each sound was designed to immerse the player in the soundscape, but also to allow players enough time to solve puzzles without becoming annoyed with the audio. All sounds have a life of their own and a resonance of memory and time that stays with the them during each playthrough of a game. In Retro City Rampage I left a sonic space for the player to wax nostalgic. In Sim Cell, I worked to breathe life into a set of sterile and synthesized sounds. Each recorded sound in Vessel is alive in comparison, telling stories of time, place and recording with them, that are all their own.

The common theme of my audio work on Retro City Rampage, Sim Cell and Vessel, is that I enjoy putting constraints on myself to inspire my creativity. I focus on what works and removing non-essential elements. Exploring the limits of constraints often provokes interesting and unpredictable results. I like “sculpting” sounds and will often proceed from a rough sketch, polishing and reducing elements until I like what I hear. Typically I remove layers that don’t add an emotive aspect to the sound design. In games there are often many sounds that can play at once, so clarity and focus are necessary when preventing sounds from getting lost in a sonic goo.

In this post I have shown how play and experimentation are fundamental to my creative process. For an aspiring sound artist, spending time with Pure Data, FMOD Studio or Wwise and a personal recorder is a great way to improve their skill with game audio. This series of articles has aimed to reveal the tacit decisions behind the production of game audio that get obscured by the fun of the creative process. Plus, I hope they offer a bit of inspiration to those creating their own sounds in the future.

Additional Resources:

- My GDC 2012 talk – My site includes an MP3 recording of the talk and the full powerpoint presentation. A full video of the talk is in the GDC Vault but requires membership

- See the Jon Hopkins Soundtrack in the Video Game Vessel video game soundtrack video by me on YouTube – shows use of Lua with music in the custom level editor : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KOyjMPPvaY4

–

Leonard J. Paul attained his Honours degree in Computer Science at Simon Fraser University in BC, Canada with an Extended Minor in Music concentrating in Electroacoustics. He began his work in video games on the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo Entertainment System and has a twenty year history in composing, sound design and coding for games. He has worked on over twenty major game titles totalling over 6.4 million units sold since 1994, including award-winning AAA titles such as EA’s NBA Jam 2010, NHL11, Need for Speed: Hot Pursuit 2, NBA Live ’95 as well as the indie award-winning title Retro City Rampage.

He is the co-founder of the School of Video Game Audio and has taught game audio students from over thirty different countries online since 2012. His new media works has been exhibited in cities including Surrey, Banff, Victoria, São Paulo, Zürich and San Jose. As a documentary film composer, he had the good fortune of scoring the original music for multi-awarding winning documentary The Corporation which remains the highest-grossing Canadian documentary in history to date. He has performed live electronic music in cities such as Osaka, Berlin, San Francisco, Brooklyn and Amsterdam under the name Freaky DNA.

He is an internationally renowned speaker on the topic of video game audio and has been invited to speak in Vancouver, Lyon, Berlin, Bogotá, London, Banff, San Francisco, San Jose, Porto, Angoulême and other locations around the world.

His writings and presentations are available at http://VideoGameAudio.com

–

Featured image: Courtesy of Vblank Entertainment (c)2014 – Artwork by Maxime Trépanier.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Sounding Out! Podcast #30: Game Audio Notes I: Growing Sounds for Sim Cell- Leonard J. Paul

Sounding Out! Podcast #31: Hand Made Music in Retro City Rampage– Leonard J. Paul

Papa Sangre and the Construction of Immersion in Audio Games- Enongo Lumumba-Kasongo

Recent Comments