“Let’s check in with Marabel May”: Audience Positioning, Nostalgia, and Format in Amanda Lund’s The Complete Woman? Podcast Series

In honor of International Podcast Day on 30 September, Sounding Out! brings you Pod-Tember (and Pod-Tober too, actually, now that we’re bi-weekly) a series of posts exploring different facets of the audio art of the podcast, which we have been putting into those earbuds since 2011. Enjoy! –JS

I’ve listened to an inordinate about of podcasts in the past year and half; the number of hours would be shocking. I’ve written about this previously: how audio, friendly voices in my ears, was a more comforting medium than television or film. In early 2021, Vulture’s Nicholas Quah published findings about the continuing rise of podcasts, suggesting that American audiences are intensifying their interest in the medium. He writes, “The case began to be made that podcasting, more so than many other new media infrastructures, was uniquely suited to meeting the moment,” suggesting that the pandemic has buoyed the medium extensively. His findings also show that podcast audiences are engaging more directly and are growing in diversity. The running joke about the medium is that everyone has a podcast. I certainly do. Comedians do. Talk show hosts do. Politicians do. In a recent episode of Bitch Sesh: A Real Housewives Breakdown Podcast, hosts Casey Wilson and Danielle Schneider joke that now every Real Housewife feels the need to start her own podcast, too.

In this 2021 moment, the series The Complete Woman? has become more relevant than ever, particularly in relation to the rise of conversations about the “Karen,” and a particular kind of white woman who attempts to wield social and racialized power. The podcast is marked as a “Baby Boomer” parody – or a fictional show directed at a fictional Baby Boomer audience. It’s eviscerating that culture, however, in its caricaturing of Marabel May and her friends, interrogating contemporary conversations about whiteness and middleclass-ness; its dark humor lies not in outdated gender roles, but in how incredibly close to home it all hits. It’s not a distant past, but a current reality.

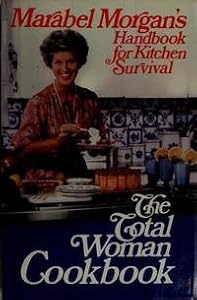

The Complete Woman podcast directly destabilizes nostalgia, even as it draws on older audio formats. In the series, comedian Amanda Lund parodies real-life mid 20th-century marriage self-help author Marabel Morgan, who promoted women’s deference to their husbands through evangelical Christianity – her book is titled The Total Woman, as mentioned by Vulture writer Nathan Rabin, a critical enthusiast of Lund’s series. The fictional Marabel May (voiced by Lund) is a housewife living in 1960s America with her husband, Freck (Matt Gourley). The Complete Woman series is set up as audio companions – diegetically understood as vinyl records – to Marabel’s book of the same name, which she penned after successfully saving her “disaster” of a marriage. She claims, “I believe it’s possible for any woman to manipulate her husband into adoring her in matter of weeks.” Each episode of the series focuses on a different aspect of womanhood or features a “checking-in” with Marabel and her “neighborhood gal” friends, aggressive Joanie (Maria Blasucci), muddled Barbara (Stephanie Allynne), and jovial divorcee Rita (Angela Trimbur).

The segments featuring Marabel chatting with her neighborhood girlfriends are particularly insightful, as each woman expresses her own warped version of the mid-century American marriage. They also combine the outdated instructional segments with more modern casual conversations, highlighting The Complete Woman’s addressing of women’s emotional labor, as well conventional housework. These segments also illuminate the distinctly female-driven nature of the series, as these voice actresses tend to improvise the discussions at hand. The back-and-forth between these women is both satirical and demonstrative of a sense of fun in their parody, and, at times, sincere friendship behind-the-scenes. Though a harsh satire of women’s positions in American culture, the show reveals a sense of community as Lund features her friends, all working comedians and actresses based in Los Angeles who find creative outlets in podcasting.

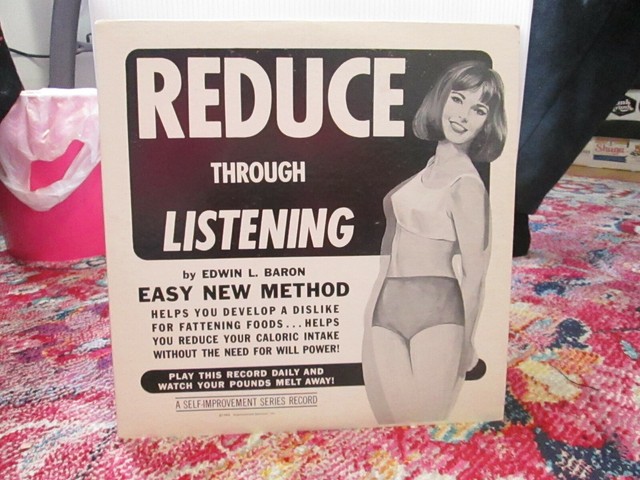

Format here, is significant too. The podcast directly satirizes an older format–self-help vinyl records–and its usage – questioning the ideologies of the past and present. The series conceptual set-up is nostalgic, but the content is not. The Complete Woman is unique in its use of format to draw on nostalgia for these pedantic vinyl recordings; the specificity of the audio and structure of the series suggests Lund has some fondness for these bygone formats. But the formatting is also used to critique and comment on the historical sexism and patriarchalism of marriage. While this is done with humor, the satire presented by the series sounds shockingly grounded in reality.

To understand the concept of The Complete Woman series, let’s examine the opening episode’s introductory narration. The first episode begins with the show’s recurring “groovy” 60s-style music, signaling a move to the past. While the show is about women for women, a male narrator is the first voice heard – an immediate indicator of Marabel May’s deference to men, and thus the imaginary audience’s, as well. The narrator states, “Welcome to The Complete Woman, the audio-companion to the number one bestselling book of the same name, written by Marabel May. It’s 1963, divorce is on the rise, the tides are changing, and marriages are drowning.”

The voices in the podcast sound echo-y and distant, reminiscent of listening to an old recording, which positions the listener as a participant – as if they are indeed in a struggle marriage and choosing to play this record and get advice from the fictional expert. Marabel then, in a deadpan manner, states, “Hi, I’m Marabel May, bestselling author, unaccredited marriage expert, and stay-at-home wife. Are you stuck in an unhappy marriage? Feel like there’s no hope in sight? You’re not alone. I receive millions of letters in the mail every day from sad people just like you. Here’s what they have to say.” Melancholic piano music starts playing as different voices – both male and female – express their unhappiness in their marriages: for example, “I mean how many nighttime headaches can one woman get?” Marabel comes back, after the sound of a record scratch, “But wait, there’s hope!” Again, the recording aspect pulls the audience into the fictional space of Marabel May and her dire need to save marriages.

The 60s-style music picks back up as the male narrator begins again, “Marabel May’s Complete Woman course is scientifically proven to improve your marriage – or your husband’s money back!” Marabel states, “But don’t take it from the faceless announcer guy. Take it from the countless, faceless, voices I’ve helped.” More voices of men and women are heard praising Marabel’s method: for example, “I used to get upset when dinner wasn’t on the table when I got home from work. Now, I know I’m right.” Marabel responds to these:

Thank you. Are you ready to take the next step toward marital bliss? You’ve read my bestselling book, now it’s time to jump into the audio companion. I suggest you listen to this record in a calm, quiet setting. Lock your children in their rooms and put your pets in a basket. Pour yourself an afternoon swizzle and settle in. You’re about to impart [sic] on a life-changing journey. Your husbands will thank you!

This exchange suggests both that the audience is enveloped into the diegesis of the podcast, but also the series’ dedication to a bygone format – though the dialog is humorous, the concept of The Complete Woman as a vinyl audio-companion never wavers.

The Complete Woman purposefully – and at times very uncomfortably – puts the listener in the position of someone who is genuinely interested in Marabel and her friends’ worldviews, who aligns with her outdated sexist and racist ideas: Marabel refers to “Oriental China,” and Barbara refers to “not being in Calcutta” when oral sex comes up in conversation. While lampooning these behaviors, the podcast is also forcing its listeners to reckon with them, to consider their own thinking as they are positioned as an audience who would agree with everything Marabel is saying.

What is additionally powerful about The Complete Woman is its reliance on authenticity in its sound. The doctrinaire voices of both the male announcer and Marabel May are so identifiable as typical affected self-help narration; their voices are upbeat but never hurry or seem too excitable – they maintain an evenness that is uncanny. Their tone and manners of speech undermine what the characters are actually saying, making this fictionalized companion album seem all the more legitimate, as if this series was found in a used record store – a kitschy yet forgotten audio self-help guide from the 60s. The intonation of the voices is overtly making fun of white voices assuming and exerting authority, no matter the absurdities that being spoken. The medium allows the audience to move in and out of positions: as genuine followers of Marabel May, as listeners of what might be a kitschy thrift store find, and as comedy fans. The sound maneuvers the audience constantly, suturing them to the aural space of the podcast in a myriad of ways.

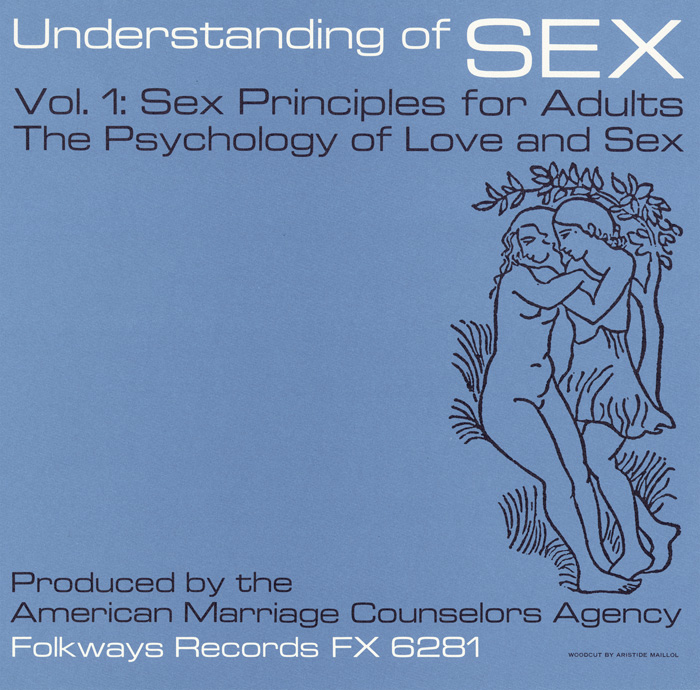

The Complete Woman parodies albums like Folkways Records produced in the mid-twentieth century, not just in its material, but also the length of the podcast episodes – a little over twenty minutes, just enough to fit perfectly on a vinyl side. The 1963 Folkways produced Understanding of Sex is a symptomatic example of precisely what the podcast is trying to mock, a pedantic authoritative voice, with liner notes boasting backing by doctors. Important, too, is the Folkways record’s completely white, heteronormative take on sex – which is here discussed solely in the context of maintaining a happy marriage. The Complete Woman’s devotion to the medium is humorous, but also in how it brandishes its critique of modern womanhood: its commitment to authenticity betrays how much Marabel’s teachings disturbingly relate to the modern moment.

The original The Complete Woman was followed up by four more series including the most recent, The Complete Christmas. I, however, want to dissect an example of scenes from The Complete Wedding’s second episode “Bridal Colors” in order to demonstrate how the series utilizes the podcasting format to position the audience as both in and out of the joke.

This episode uses sound to highlights the absurdist, yet bitingly relevant, commentary on wedding planning, both then and now. “Bridal Colors,” with women’s discussion of picking the perfect dress and color scheme for their weddings, especially underlines not only the parody of mid-century culture, but contemporary obsession with wedding planning. With the internet and influencer culture as an endless source of consumption, advice, and color palettes, modern wedding planning does not seem so different from Marabel’s suggestions – particularly in how both exude whiteness, middleclass-ness, and heteronormativity. Those resonances suggest that, despite The Complete Woman parodying a mid-century mindset and the use of older sound technologies, the analog and the digital are applied in very similar ways to maintain a status quo.

After giving the audience a quick quiz to help them figure out their “seasonal” colors, Marabel gives some specific suggestions for planning the perfect wedding. It is important to quote her entire speech on wedding scenarios in its entirety to fully understand how the series uses voice in concert with content to create its cutting yet absurd nature. Marabel speaks, as she always does, in a clear, enthusiastic, pedantic, very raced and gendered voice:

It’s science! – but for ladies. I’ll walk you through a few likely scenarios. I suggest taking notes with a pencil and paper. If you don’t have access to pencils or paper, chocolate syrup on a large cutting board is your best bet. If you’re a Winter having a city hall wedding, try a tea-length going away dress or a handsome woolen ensemble in French white with a veil-less headdress. Your flowers may be carried as a sheath or as an old-fashioned nosegay, pinned to a prayer book. Muffs are encouraged but not required. If worn, they must be flame-retarded [sic] or pre-burned. If you’re a Spring having a formal church wedding, try a long-trained brocade dress in true white and carry an impressive bouquet of American beauty roses, along with an ivory rosary. Jewelry may be delicate and preferably real. No feathers! – unless of course it’s a live canary, pinned to a broach borrowed by your mother-in-law’s estranged secretary. If you’re a Summer having a semi-formal wedding at home, try an ankle-length silk organza garden dress in bridal blush. Shoes are optional, but if worn must be made of glass blown by your tallest male relative on your maternal side. Sarah Bernhardt peonies are appropriate but no more than a half-dozen lest you come off looking braggadocio… is a word I learned!

Marabel’s voice is very candid, and she speaks quickly, as if this ridiculous list of arbitrary rules is a reminder for the audience of concepts of which they’re already aware. This monologue is exemplary of the series’ style – twisting banal aspects of material culture into absurdity to highlight the pressures put on women to perform and perfect things like weddings, marriage, and motherhood. “It’s science! – but for ladies” focuses on this fictional ideal that there is a formula that can lead to the perfect marriage, or that any aspect of idealized womanhood can be perfected if you just follow these easy steps. Woman’s work is implied here to be banal, because it is something expected, and if one fails, the consequences are dire.

While listening to Marabel go on is wildly absurd, it is also mocking a one-size-fits all mentality about weddings, and womanhood in general. The wedding comes to represent a particularly coded – white, middleclass, heteronormative – aspirational cultural practice that, in this midcentury moment of Marabel, is becoming solidified as something one is “supposed to do” and supposed to do in a certain way. It suggests to the audience, too, that these practices, while shifting, haven’t completely gone away. There are still expectations, traditions, and rituals that are widely expected to be performed by woman, relating not just to marriage, but work, sex, motherhood – the list goes on. This midcentury moment is still strongly felt in the contemporary moment, so as Marabel rattles off a list of what seem like insane rules – “Shoes are optional, but if worn must be made of glass blown by your tallest male relative on your maternal side” – they aren’t all that far off from today. These notions of perfected womanhood, too, are strongly structured by ideals held over from that time about race, class, and gender.

In “Bridal Colors,” the ladies of The Complete Woman also sit down to reminisce about their wedding themes – though Marabel is initially keen on having the ladies recall their roles in her own special day. When Marabel uncouthly mentions how much salve she used to clear up the many bug bites she received at Barbara’s backyard wedding, Rita sunnily jumps in with, “You know a little trick is you put toothpaste on ‘em.” Marabel, comically deadpan, replies (you can hear the massive eyeroll just from her voice), “Oh, Rita.” Heard on the recording, the voice actresses all burst out laughing at what sounds like an improvised moment. The absurdity of their conversation is brought to a halt by an honest suggestion, and it is quickly incorporated into the scene.

Voices shaking with a bit of laughter are heard throughout the series, but this stands out as particularly noticeable. It highlights the improvised nature of some of these group scenes by audibly breaking both the ‘60s narrative and the aesthetics of many contemporary hyper-edited studio podcasts. It would not be unheard in either moment to cut out the laughter or re-record the scene, but it is kept in, obvious to the audience. This laughter breaks the authenticity to the medium and works to successfully suture the podcast space to that of contemporary listeners. There is no frame to restrict, not only what can be heard, but what can be said. The diegesis spills into the space of the audience – they, too, are in the joke, for a moment no longer positioned as the fictional audience of Marabel May, but a comedy podcast audience. This builds a sense of community between listener and creator, as seemingly intimate moments of gaffes become integral to the both the diegesis of the podcast, but also the listening experience. In the case of The Complete Woman the format welcomes mistakes and improvisation as voices break out of characterization to comment on the reality behind the format – which is itself an important part of podcasting.

The comedy of The Complete Woman series is dark at times, as Lund notes both the limitations of women’s roles throughout the 20th century and highlights the ways in which things have not changed. While The Complete Woman is not directly calling on its audience to act, it is addressing the complexities of nostalgia for a previous moment by noting how, in some ways, it closely resembles the contemporary one. There is nostalgia found in the audio-companion concept of the series, but the content – while humorous – can be quite deep and painful. The Complete Woman does not succeed because it draws fondly on former sound technologies, but rather because it – often harshly – points out the pitfalls of nostalgia; Marabel May’s twisted world of the idealized straight white 1960s middle class housewife is often a direct commentary on the current position of women. The show suggests both that this kind of thinking hasn’t shifted much, but also, and more significantly in this moment, the conversation surrounding middle class white women’s complicity in upholding systemic racism. While the original The Complete Woman was released years before these conversations became widely prevalent, it holds up a satirical, yet bitingly revelatory mirror to the contemporary moment.

The podcast also amplifies the voices of the community of women behind it, who are looking critically at this moment in history by reframing and reengaging. It is worth noting Lund is a cofounder of the women-run Earios podcast network, that “strives to elevate the podcasting market with intelligent, diverse, subversive content BY WOMEN, FOR EVERYONE.” It is through comedy – ironically and inaccurately territorialized as a very “masculine domain” in the U.S. entertainment industry – and the genuineness of these scenes which break open the diegetic sound space of the podcast, that the audience can hear – and connect to – the very real women behind-the-scenes of the parody. Ultimately, through looking at series like The Complete Woman, it becomes clear that podcasting is more than a return to familiar formats (radio) – it is creating something new. Improvisation and comedy are particularly significant: the moments of improv and mistakes can create genuine connection.

—

Megan Fariello is a Chicago-based writer with a background in cultural studies. She is currently a contributor with Cine-File, and has recently published work in Film Cred and Dismantle. Megan is also a PhD graduate from the Cultural Studies program at George Mason University. This article draws and expands on work from her dissertation, titled The Techno-Historical Acoustic: The Reappearance of Older Sound Technologies in the Contemporary Media Landscape, which intervenes in the disciplines of cinema and media studies and sound studies, examining how the rise of aurally-focused narratives in contemporary media – including television and podcasting – are recasting processes of nostalgia.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Vocal Gender and the Gendered Soundscape: At the Intersection of Gender Studies and Sound Studies–Christine Ehrick

Gendered Voices and Social Harmony–Robin James

A Manifesto, or Sounding Out!’s 51st Podcast!!! – Aaron Trammell

This Is How You Listen: Reading Critically Junot Diaz’s Audiobook-Liana Silva

Recent Comments