Becoming Sound: Tubitsinakukuru from Mt. Scott to Standing Rock

In the Numu tekwapuha, the Comanche language:

Haa ma r

uawe, haa nuhaitsi. Nunahnia tsa Dustin Tahmahkera.

In this post, I talk about the phrase “becoming sound,” and also gesture to several examples across Indi’n Country to encourage us to listen for aural affirmations and disavowals of indigeneity and encourage active reflection on the roles of sound in becoming and being indigenous, now and in the future. By “becoming sound,” I’m interested in the interdependent relations between emitting sound as the formations of sonic vibrations in the air and becoming sound as a method toward restoring good health through cultural ways of listening and healing.

While the former use of sound gets situated more in sound studies, the latter sense of “sound” is evoked more by the medical humanities, such as when saying someone is “of sound mind,” though we know from the history of perceptions of mental illness that what constitutes a “sound mind” is not resoundingly agreed upon. For example, the U.S. heard the Paiute Wovoka’s visionary Ghost Dance and singing for peace and “becoming sound” again as “savage” and “insane,” and sent the 7th Cavalry to massacre Lakota children, women, and men in response. The misdiagnosis of “savage” has instilled a puritanical, restrictive worldview of what “being sound” means, and it’s been abused and amplified all the more in the metaphorically schizophrenic split between becoming “Indian, an unsound Indian,” and re-becoming a “sound indigenous human being.”

My thoughts here echo an epistemology of sound and being by the late John Trudell. In Neil Diamond’s 2009 documentary Reel Injun, Trudell theorizes on collisions between schizophrenic-like identities located in an expansive soundscape. He says:

600 years ago, that word ‘Indian,’ that sound was never made in this hemisphere. That sound, that noise was never ever made … ever. And we’re trying to protect that [the Indian] as an identity. … we’re starting not to recognize ourselves as human beings. We’re too busy trying to protect the idea of a Native American or an Indian, but we’re not Indians and we’re not Native Americans. We’re older than both concepts. We’re the people. We’re the human beings.

Following Trudell’s call for becoming the people again, and for resisting what he calls the genocidal “vehicle [that tries to erase] the memory of what it means to be a human being,” my attention, my ear bends toward asking about the roles of sound in human being-ness and toward the roles of listening in that ongoing process of becoming sound human beings, a process cognizant of the “cacophonies of colonialism,” as sounded forth by Jodi Byrd in The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism, and a process also grounded in indigenous sonic traditions and modernity.

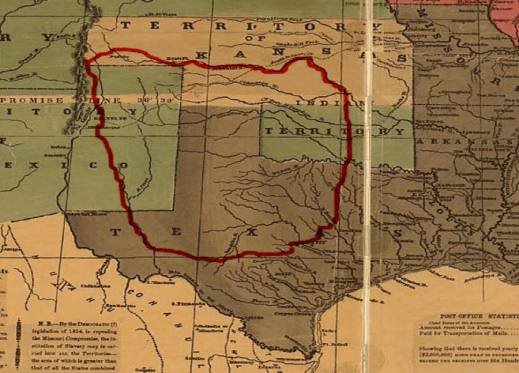

What I’m sharing is in support of an emerging multimedia research lab, podcast, and book project I call Sounds Indigenous, a title which affords considerable space in sonic clashes between how indigeneity gets heard and unheard, how it is sounded and unsounded. Sounds Indigenous involves listening for sonic sovereignty in indigenous borderlands. For me, it’s particularly located in the Wichita Mountains in Oklahoma and elsewhere in the 240,000 square miles of Comanche homelands known as la Comanchería.

As for method, Sounds Indigenous practices tubitsinakukuru, our word for listening carefully.

As I recently wrote elsewhere in a special indigenous-centric issue of Biography, “Nakikaru means listen, but to practice tubitsinakukuru is to listen closely and engage with the speakers and sounds, be they familiar or foreign, friendly or fierce, fictive or factual, or sometimes, in the eccentricities of humanity, all of the above.” It goes back to one’s beginning. As Muscogee Creek artist Joy Harjo says in her co-edited collection Reinventing the Enemy’s Language: “We learn the world and test it through interaction and dialogue with each other, beginning as we actively listen through the membrane of the womb wall to the drama of our families’ lives” (19).

In the context of colonialism, this project is about listening, too, through sonic dissonance. From the Latin word for “not agreeing in sound,” dissonance represents the disharmonius, that which lacks in agreement. But more importantly, it’s about using, not disavowing, the dissonance as audible ground from which to reimagine indigenous futures toward becoming sound. In an indigenous sound studies context, it means listening through Byrd’s “cacophonies of colonialism,” through ear-splitting “discordant and competing representations” of Indianness and indigeneity (xxvii). We know that what sounds indigenous often becomes sites of debate and critique, such as when hearing what Phil Deloria calls “the sound of Indian” (183) in Indians in Unexpected Places, be it the boisterous nonsensical grunts and ugs in cinema, the cadence of the tomahawk chop at sporting events, the clapping hand-to-mouth of cowboys-and-Indians televisual and school playground lore, or early ethnologists’ mis-hearings of indigenous songs across Indian country, all the performative made-up stuff of non-Native imaginaries that all too often makes up the popular “sonic wallpaper” of Indianness (222).

Harley Davidson “Indian” Motorcycles, Parked atop Mt. Scott, Image by Author

At the same time, Sounds Indigenous is also about the soundscapes, the sonic formations, of Comanches and other Natives. It’s about indigenous auditory responses, which includes not only the vocalized, the heard, but also sampling the “certain quality of being” that Africana Studies scholar Kevin Quashie calls “the sovereignty of quiet” in his study of the same title. Sounds Indigenous is about those auditory responses and expressive ways of sounding indigenous that reverberate through and against what my Mapuche colleague Luis Carcamo-Huechante calls acoustic colonialism, and what Ronald Radano and Tejumola Olaniyan call the “audible empire” (7): “the discernible qualities of [what] one hears and listens to—that condition imperial structurations.”

With that said, this is a nascent mix and remix of words in an always already failed search of communicating the ineffable: these are words in search of communicating holistically about sonic affect. Sonic affect is about far more than just “sound” or just “listening.” Sonic affect is also not just about the subjectivity of how certain sounds make us feel certain ways, but rather it is what deeply makes soundings possible and brings forth our expressions of and feelings about sound. Affect is not just emotion; affect is what allows us the capabilities to feel emotion.

The road to Mt. Scott, Image by author

Yet even with the ineffability of affect, “every word,” Trudell tells us, “every word has power” as we turn each word “into sound … into the world of vibration, the vibratory world, the vibration of sound. It’s like throwing a pebble,” he says, “into the pond. Something happens.” The “something” from words and other sounds may not be fully communicable in sonic expressions, but I’d like to think we know of the something when we hear it and feel it as human beings, even if it’s a recognition of seemingly unknowable mystery, especially in moments of what media scholar Dominic Pettman calls “sonic intimacy,” a process of “turning inward…to more private and personal experiences and relationships” in Sonic Intimacy: Voice, Species, Technics (or, How To Listen to the World), (79), such as seen and heard in this personal video I took with my phone during a sunset in early 2014 while sitting with my son Ira atop Mt. Scott, the tallest peak in the Wichita Mountains.

For me, Mt. Scott has long been one of the most remarkable sites in the world, a sacred site carrying a long history with Comanches but that for many may be just another tourist destination.

As a Comanche born in Lawton, Oklahoma, who grew up mostly just south of there in the Wichita Falls, Texas, area, I have crossed the Pia Pasiwuhunu, the Red River, innumerable times and visited nearby Mt. Scott, climbing its boulders with friends or driving on the roadway that snakes around it to the top.Once at the top, I, like my g-g-g-grandfather Quanah Parker, the most famous of all Comanches, have sat there: observing, listening, exploring, and praying. But as you may have heard from other folks’ voices in the background of the video with my son, it can be difficult these days to “get away” on Mt. Scott. You may hear tourists laughing, loud talking on cell phones, rocks being thrown, and the revving of Harley Davidsons or, better yet, Indian motorcycles in the now-spacious parking lot at the top.

The loudest noise, though, comes from nearby Fort Sill. Named after Joshua Sill who died in 1862 in the Civil War, it began in 1869 as an outpost against Comanches, Kiowas, and other Native Peoples. Now a military base that has been known to sometimes still go against us, Fort Sill is known for its Field Artillery School and, for those in the Wichita Mountains and Lawton where the base is located, known for its sonic booms of artillery testing, guns, bombs, missiles, and tanks as seen here in an old Fort Sill training film.

Over the decades, it’s become what some might consider elements of a naturalized and normalized soundscape. As long as I can remember, the sounds of artillery have been there, somewhere, in experiences of being in the Wichita Mountains; but not everyone interprets those sounds similarly. The author of the 2001 LA Times article “Military Booms Are Boon to Okla. Base’s Neighbors” claims you “would be hard-pressed to find anyone who doesn’t welcome the disruption.” They quote local residents saying things like “We do live with the boom-boom-boom of artillery fire 24 hours a day, but it’s very interesting about living here, you just don’t hear it anymore.” One former Fort Sill general-turned local banker says, “That’s the price you pay when you live in a community like this. To us, it is oddly comforting. It’s the sound of a healthy economy and a viable place to live.” Another Ft. Sill general adds, “At times the noise is bothersome. But it’s proof positive that we are still conducting our mission here. And the people of Lawton derive comfort from that.” A former mayor of Lawton says, “When I hear those guns out there popping, that’s the sound of freedom ringing in my ears …That’s the freedom bells ringing. Those are the guns that are going to be fired if we have to defend the United States of America.” Such rhetoric, spoken in the 21st-century, sounds rather reminiscent of Fort Sill’s origins in defense against the indigenous.

Still, it’s complicated, to be sure, made even more so by the fact that I come from a strong military family–of all Comanche families, Tahmahkeras rank second in having the most veterans and I’m proud of that, I’m proud of my relatives. Still, there’s something about the blasts hovering through the air and over our homelands. There’s a reminder, of imagined sonic memories of weaponry used against our Comanche ancestors, like “the world’s first repeating pistol, the” “‘Walker Colt’ .44 caliber revolver” that the Comanche Paul Chaat Smith says was “designed for one purpose: to kill Comanches.” As a Comanche elder recently told me in response to Fort Sill’s artillery explosions, “it’s not easily something you can overcome because it brings back the memories of over 150 years ago,” of what happened to the people.

Still, it’s complicated, to be sure, made even more so by the fact that I come from a strong military family–of all Comanche families, Tahmahkeras rank second in having the most veterans and I’m proud of that, I’m proud of my relatives. Still, there’s something about the blasts hovering through the air and over our homelands. There’s a reminder, of imagined sonic memories of weaponry used against our Comanche ancestors, like “the world’s first repeating pistol, the” “‘Walker Colt’ .44 caliber revolver” that the Comanche Paul Chaat Smith says was “designed for one purpose: to kill Comanches.” As a Comanche elder recently told me in response to Fort Sill’s artillery explosions, “it’s not easily something you can overcome because it brings back the memories of over 150 years ago,” of what happened to the people.

In response to the militarized sonic booms, I’m intrigued by an idea sounded forth by four-time Comanche Nation chairman Wallace Coffey. In the early 1990s, Coffey wrote a letter to then-Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney at a time when the U.S. Government was shutting down Army bases. In a 2010 interview with Coffey recalls telling Cheney “to close Ft. Sill down and give it back to the Comanches, and we will heal it. Instead of bombing this land, we will heal it.” As he told me in a conversation in the Wichita Mountains in June 2017, “We may not be the titleholders [over all our homelands now], but we are still the caretakers.”

It brings to mind an old story from the late 1860s, that illustrates how one culturally-informed Comanche back then listened to militarized sounds. As Chickasaw citizen and retired Ft. Sill Museum director Towana Spivey recounted in his email to me on June 10, 2017: when generals Sheridan, Grierson, and Custer went “to the Medicine Bluffs area,” long held as a sacred site but also is where Ft. Sill is now located, “the soldiers gathered to explore the imposing bluffs along the creek” and “noticed the echo effects when shouting or discharging their weapons in the basin in front of the steep bluffs.

They continued to fire their weapons to create a corresponding echo.” In response, Asa-Toyet, or Gray Leggings, a Comanche scout who accompanied them, “was,” Spivey says, “particularly horrified with their antics in this sacred place.” To Asa-Toyet’s hearing and sensibility, those “antics” may suggest what I’d call sonic savagery on the part of the soldiers. They wanted him to climb to the crest with them, but he told the soldiers he was not sick, thus “reflecting the traditional [Comanche] belief that there was no reason to access the crest unless you were suffering from some malady.”

Medicine Bluffs is sacred for many Comanches, such as our current tribal administrator Jimmy Arterberry who says, “Medicine Bluffs is the spiritual center of my religious beliefs and heart of the current Comanche Nation.” You can imagine, then, the opposition to when the U.S. Army, in 2007, sought to build a $7.3 million warehouse for artillery training. When they proposed building it “just south of Medicine Bluffs,” in which certain views would be obstructed and Comanche ceremony disrupted, word eventually got to Towana Spivey who curiously had been left out of communications. As detailed in Oklahoma Today, “The Guardian,” Spivey, a cultural intermediary and longtime educator to Ft Sill leadership about practically anything indigenous, intervened immediately. He talked with Comanches who were obviously against the proposed warehouse. He also tried to talk with certain army officials; but for that, he received a loudly written order that read, and I quote, “Do Not Talk to the Indians,” a blatant attempt to try to silence the indigenous who gets reduced to that category of Indian that Trudell critiques. The Comanche Nation soon sued the Army, and the Comanches won, thanks in part to Spivey, who had been “subpoenaed to testify for the plaintiff.” U.S. District Judge Tim DeGiusti ruled that the U.S. Army failed to consider alternate locations and that “post officials” had “turned a deaf ear to warnings” from Spivey. Those warnings, I’d add, were indigenous-centered by a Chickasaw and U.S. ally of the Comanches who recognizes us as Trudell calls forth: as human beings.

In the audible imaginary of sonic duels and dissonance between the Indian and the people/human beings, the list grows elsewhere in Indi’n Country. Consider when Greg Grey Cloud was arrested in 2014 for singing an honor song (not chanting, as some media outlets reported), but an honor song “to honor,” he says, “the conviction shown by the senators” “who voted against the Keystone XL pipeline, Grey Cloud sings even as self-identifying Cherokee, Senator Elizabeth Warren, calls for order.

Or consider, too, when just last year, indigenous honor song singers and their handdrums at Standing Rock were met by LRADs, Long Range Acoustic Devices, among other weapons.

The LRAD Corporation boldly claims its device “is not a weapon,” with the “not” in bold typeface, underlined, and italicized as if that makes it true. They prefer the description “highly-intelligible long-range communication device.” Following echoes of Indian hating from the so-called “Indian wars” of history, reports came in of police confiscating handdrums, suggestive of fearing the sounds and songs they do not recognize. Laguna Pueblo journalist Jenni Monet quoted Arvol Looking Horse who said police “took … [ceremonial pipes]” and “called our prayer sticks weapons.” Ponca activist and actress Casey Camp-Horinek was there, too, singing while surrounded by other elders, a circle of human beings. She later reflected that “I’ve never felt so centered and grounded and protected as I did at that particular moment.”

Image by Flickr User Dark Sevier, Standing Rock, 4 December 2016, (CC BY-NC 2.0)

“Even the noise cannon,” she adds, “didn’t effect me.”

In closing, the sonic dissonance reverberates between sites such as indigenous honor songs in support of tribal and planetary well-being, and the militarized sonic responses—from artillery testing near Mount Scott in Comanche country to sound cannons and the confiscation of sacred drums in Standing Rock—that attempt to silence indigenous soundways. But no one can silence us, including, for example, the Kiowa Zotigh singers here and their honor song for Standing Rock. No one can fully silence us from sounding forth, in efforts toward becoming not unsound Indians but becoming sound human beings.

And by the way, the next time that Ira and I travel to the top of Mt. Scott, we will listen again … we may hear artillery explosions and other sonic reminders of colonialism, but what we’ll also hear are ourselves, breathing, sounding, and becoming Comanche, becoming Numunuu, as we call to the mountain in taa Numu tekwapuha, in our Comanche language. Remember, Mt. Scott is the colonizer’s name. . .but we also have our own names for it, names that historically sustained us as being sound human beings speaking the Numu tekwaphua, and names that can continue to help us become sound now and in the future. Udah, nu haitsi. Thank you.

—

Featured Image: Greg Grey Cloud escorted from the Senate gallery, image from the Indoan Country Media Network

—

Dustin Tahmahkera, an enrolled citizen of the Comanche Nation of Oklahoma, is a professor of North American indigeneities, critical media, and cultural sound studies in the Department of Mexican American and Latina/o Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. In his first book Tribal Television: Viewing Native People in Sitcoms (University of North Carolina Press, 2014), Tahmahkera foregrounds representations of the indigenous, including Native actors, producers, and comedic subjects, in U.S., First Nations, and Canadian television from the 1930s-2010s within the contexts of federal policy and social activism. Current projects include “The Comanche Empire Strikes Back: Cinematic Comanches in The Lone Ranger” (under contract with the University of Nebraska Press’ “Indigenous Films” series) and “Sounds Indigenous: Listening for Sonic Sovereignty in Indian Country.” Tahmahkera’s articles have appeared in American Quarterly, American Indian Quarterly, and anthologies. At UT, he also serves on the Advisory Council of the Native American and Indigenous Studies program.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Sounding Out! Podcast #40: Linguicide, Indigenous Community and the Search for Lost Sounds–Marcella Ernst

The “Tribal Drum” of Radio: Gathering Together the Archive of American Indian Radio–Josh Garrett Davis

Sonic Connections: Listening for Indigenous Landscapes in Kent Mackenzie’s The Exiles–Laura Sachiko Fugikawa

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Recent Comments