Black Mourning, Black Movement(s): Savion Glover’s Dance for Amiri Baraka

I don’t worry about the look of it so much. Choreography comes later, when I’m putting together a piece. I’m into the sound; for me, when I’m hittin’, layin’ it down, it’s all about the sound. –Savion Glover, My Life in Tap

It has been a little over a year since Amiri Baraka passed, and still I hear the echoes of his presence. I am especially attentive to the ways his work has been carried on by those involved in recent black uprisings in Ferguson, New York City, and Baltimore. Powerful political poetics that have emerged from these events include work by Danez Smith, Claudia Rankine and the many contributors to blackpoetsspeakouttumblr.com.

And yet, part of what I’ve witnessed in the streets, actual physical spaces of public protest against police violence and systemic racial oppression, is an example of what Thomas DeFrantz has termed “corporeal orature,” or the ability of bodies to resonate throughout public space and shift political discourse. In these moments, the body talk of protesters is not simply the sound of clattering feet through city streets, but a commitment to the ways in which physical gestures can speak truth to power. I am especially interested in connecting Baraka’s legacy to the larger conversation about the aural kinesthetic that Imani Kai Johnson has proposed, and in teasing out the various dimensions and potentials embedded in that category.

Dance at Ferguson Protests, 2014, Image by Shawn Semmler

For me, Savion Glover exemplified the lingering sound of Baraka’s spirit in his tap dance at his memorial service. Whenever I listen to the recording—which still brings tears to my eyes—I am reminded of the abundant sense of joy, sadness, and love that characterized Baraka’s service. Listening to Glover’s dance is an aural kinesthetic experience, like watching a comet pass across the night’s sky. I am reminded, too, of the way I clamored to record that moment, to keep a piece of the poet alive on my iPhone even after his public passing. And indeed, that performative sound of feet tapping, that measured excess of the body produced through movement, has kept Baraka alive for me; like his groundbreaking work, it is powerfully resistant to the proper rubrics of any one discipline except, perhaps for the study of sound itself.

So, this post then, is about tap dance and its ability to sound out Baraka’s name and life. But in a larger context, the intricate vibrations of Glover’s performance facilitate a deeper understanding of the relationship between sound and mourning, and a kind of mourning that is particularly African American, that is to say, American. It is a mourning that exists beyond the word, written text, or image and a sound practice that enables the bereaved to make a joyful noise and a mournful one at the very same time. So I ask, how do you write a eulogy with the body? How do you perform an embodied love? What does Black love and a reverence for Black life sound like? Sometimes, the answer is tap.

Audio Clip of Savion Glover’s Dance at Amiri Baraka’s Funeral, 18 Jan 2014

The dance explodes on stage like a burst of light. It begins with something approximating a drum roll – and then hard slow taps, hammering away like someone at a typewriter, I imagine, or a train gaining steam.

It is coming.

Slow, insistent and strong, with a little riff now and then, a little picking up of speed here and there. It is coming on louder now, that explosive thing, the tension you are noticing. He is doing the thing. And then there is that skillful, smooth, strong tap. Glover is at work, y’all.

Savion Glover at Work, Image by Flickr Users Raquel and Soren

As a tribute to Baraka, Glover’s dance bears numerous stylistic implications. Among them, I understand the rhythm of Glover’s tap as the rhythm of writing, an aesthetic that complicates the way his dance can be understood as a manifestation of the black vernacular. Sketching out the early connections between her son’s artistry and the percussive taps of the keyboard, Yvette Glover says. “‘I was working for a judge, as an assistant, when I was pregnant with Savion…And when I would type, and the carriage would automatically return, he’d walk, he’d follow it, in my stomach. You could see him move” (39). He does it still. In the audio clip, Glover’s footwork evokes the dexterity of Baraka’s language, all the while telling a story of its own.

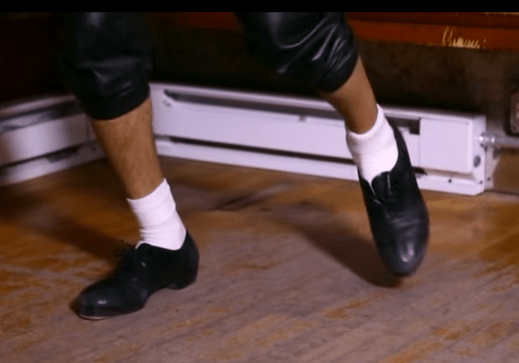

Savion Glover’s Shoes, Sadler’s Wells, 2007, Image by Tristram Kenton

But what about the intensity of the dance, its crescendo toward the end of the service, a flurry of percussive steps beside Baraka’s coffin? Baraka himself reminds us this particular musicality is so necessary here. In his discussion of “Afro-Christian Music and Religion” in Blues People, Baraka notes that in Black diasporic religious services, “the spirit will not descend without a song” (41). Glover’s dance takes place at a moment in the service when emotion exceeds the power of language, but not sound. He uses his body as an instrument of sound in its fullest sense. His performance is a choreography of embodied sound: full-on and at-once body poetry, mourning and tribute.

Elucidating the use of his body as an instrument of sound, Glover declares:

It’s like my feet are the drums and my shoes are the sticks[…]My left heel is stronger, for some reason, than my right; it’s my bass drum. My right heel is like the floor tom-tom. I can get a snare out of my right toe, a whip sound, not putting it down on the floor hard, but kind of whipping the floor with it. It get the sounds of a top tom-tom from the balls of my feet. The hi-hat is a sneaky one. I do it with a slight toe lift, either foot, so like a drummer, I can slip it in there anytime. And if I want cymbals, crash crash, that’s landing flat, both feet, full strength on the floor, full weight on both feet. That’s the cymbals. So I’ve got a whole drum set down there (19).

Combining his body’s drumbeat with the tic of Baraka’s keystrokes, Glover embeds the pattern of Baraka’s life in this tap dance, communicating it with the kind of deep and reverential love you are taught to have for your elders when you are young, appropriate and deep.

But as powerful as his body-poetry is, Glover’s silences are also key. In those inaudible spaces, Glover spreads out his arms, offering up the dance in a gesture of expansive love; the immensity of the silent gestures mirroring the immensity of Baraka’s life. He holds it out as a gift towards the audience, bows his head, too.

But as powerful as his body-poetry is, Glover’s silences are also key. In those inaudible spaces, Glover spreads out his arms, offering up the dance in a gesture of expansive love; the immensity of the silent gestures mirroring the immensity of Baraka’s life. He holds it out as a gift towards the audience, bows his head, too.

In moments of sound and silence, the audience calls out to Glover the way they would a preacher. At these moments, the dance becomes a call and response akin to the way Baraka’s life’s work was a call and response. A call to respond. A call to take what was given to you and make it mean. Listeners to the dance are called up out of themselves. We are changed by the dance and by the listening.

Tap tap tap.

Glover’s performance shows us how his specific blend of African and European dance traditions exists in a spiritual and artistic dimension. There is a religious explanation for this, too. In African Dance, Kariamu Welsh-Asante explains the function of the African funeral dance in definite terms:

All African dances can be used for transcendence and transformational purposes. Transcendence is the term usually associated with possession and trance. Dance is the conduit for transcendent activities. Dance enables an initiate or practitioner to progress or travel through several altered states, thereby achieving communication with an ancestor to deity and receiving valuable information that he/she can relate back to the community. Repetition is key to this process as it guides the initiates, or dancers, through the process of the ceremony. The more a movement is repeated, the greater the level of intensity and the closer a dancer gets to the designated deity or ancestor. Transformation means to change from one state, or phase, to another (16).

Glover certainly brought us close to Baraka. And yet, I would go a step further to suggest that this is, above all, blues dance. As such, it reveals continuing relevance of social dance and movement to Baraka’s political legacy. Baraka and Glover work directs us towards the propulsive nature of black social/percussive dance forms. These sonic gestures clarify the ways black life matters, impacts the public sphere and policy. The politicized nature of Black Arts Movement performances and the performative elements of contemporary Black protest are still linked through sound. Politicized Black aesthetics continue to offer us multiple opportunities to witness the convergence of sound and movement. Ras Baraka, affirms this in his own eulogy for his father:

Have you seen black fire it burns deep it never goes out you can try and extinguish it but it never goes out it never goes out it never goes out only up or out as in broad as in multiply as in blues black base of the fire dancing flickering at times but never all the way gone dancing flickering at times but never all the way gone…

The power of the dance, of the Black Movement to move is still with us.

Protestors dance to a community band, Baltimore, MD, 28 April 2015, Photo by Adrees Latif/Reuters

—

Featured Image, Screen Capture of Savion Glover dancing by JS

—

Kristin Moriah is the editor of Black Writers and the Left (Cambridge Scholars Press, 2013) and the co-editor of Adrienne Rich: Teaching at CUNY, 1968-1974 (Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative, 2014). Her critical work can be found in Callaloo, Theater Journal, TDR and Understanding Blackness Through Performance (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). Moriah is completing a dissertation on African American literature and performance in transnational contexts at the CUNY Graduate Center. Her research has been funded through grants from the Social Science and Humanities Council of Canada, the Freie Universität Berlin and the Graduate Center’s Advanced Research Collaborative. She is a 2014-15 @IRADAC_GC Archival Dissertation Fellow and spring 2015 Scholar-in-Residence at the NYPL Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Sometimes she tweets via @moriahgirl.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“HOW YOU SOUND??”: The Poet’s Voice, Aura, and the Challenge of Listening to Poetry-John Hyland

Pretty, Fast, and Loud: The Audible Ali–Tara Betts

The Sounds of Anti-Anti-Essentialism: Listening to Black Consciousness in the Classroom-Carter Mathes

Sonic Spirituality: Meditations on Eminem’s “Beautiful” and “My Darling”

Guest writer Marcia Alesan Dawkins’s new book on rapper Eminem, Eminem: The Real Slim Shady is now available. We here at Sounding Out! are thrilled, so for this week’s post we asked Dr. Dawkins to give us a glimpse into a side of the notorious rapper that few may have heard: the intersection between artist and spirituality. This comes just in time too, considering Kanye West’s latest release, Yeezus, not to mention Touré’s recent biography of Prince, I Would Die 4 U: Why Prince Became an Icon (2013), which examines the confluence of celebrity and spirituality for a generation of Prince fans. Without further ado, give it up for Dr. Dawkins! Pump it up pump it up pump it up! —Liana M Silva-Ford, Managing Editor

Eminem caught my ear a year before The Slim Shady LP hit record stores in 1999, when I came across a single released by Rawkus Records called “5 Star Generals” (1998) on which he made a guest appearance. I would later learn that this was an old track the rapper recorded for cash while he was unsigned and then forgot. Nevertheless, Em’s first lines about sinning boldly, shooting nuns in Bible class, and damning hell itself hit me like a ton of bricks. I knew that lines like his, which were sure to enrage anyone within earshot, would make him (in)famous.

To my surprise, I learned a year later that my 89-year-old Cuban American grandfather, a poet and a reverend, had been listening to Eminem too. This struck me as strange for two reasons. First, my grandfather wasn’t fluent in English. Second, he’d never expressed much interest in rap music other than commenting that he noticed kids rapping in the parks near his house in Hollis, Queens every now and then. Of course, I knew that many of those boom-box-toting kids were now superstars like Run-DMC and LL Cool J, but my Grandfather didn’t.

When I entered the living room to the sound of Slim Shady, my grandfather sat transfixed. After the song ended, I asked him if he knew what he was hearing. Sitting up in his blue La-Z-Boy recliner he said, “I’m listening to some guy who calls himself Eminem. I can tell he’s probably a heathen and I don’t care. I love what he’s doing with his words.” I was shocked. My grandfather went on to tell me that despite the obvious language and experiential barriers that stood between him and Eminem, he was in awe of the way the rapper was using his voice and his words as instruments. What really got me was when my grandfather said that Eminem’s unapologetic tone reminded him of many preachers’ fiery delivery over the years. I could not believe it. Grandpa’s encounter with Eminem was not just sonic. It was spiritual.

Fifteen years later I am still listening for what my grandfather heard. In the process, my ears have been captivated by Eminem’s sonic spirituality, open to its every sound. So open, in fact, that I dedicated three chapters in my forthcoming book to understanding how his music can be seen as a dynamic sphere of spiritual activity in terms of guilt-purification-redemption, love-hate, and relationship-awareness. While paying attention to Eminem’s sonic spirituality began as a personal exercise, it now represents an important part of understanding how spirituality operates culturally and is just like sound: recognizable, uncontainable and elusive.

Fifteen years later I am still listening for what my grandfather heard. In the process, my ears have been captivated by Eminem’s sonic spirituality, open to its every sound. So open, in fact, that I dedicated three chapters in my forthcoming book to understanding how his music can be seen as a dynamic sphere of spiritual activity in terms of guilt-purification-redemption, love-hate, and relationship-awareness. While paying attention to Eminem’s sonic spirituality began as a personal exercise, it now represents an important part of understanding how spirituality operates culturally and is just like sound: recognizable, uncontainable and elusive.

In other words, I’ve finally understood what my grandfather was trying to tell me — how, rather than simply what, he heard in Eminem’s music. Here’s the revelation: sonic spirituality is a listening attitude, a personalized relationship with music that allows us to mark time, experience the intangible, track movement, engage otherness and, in the end, encounter more honest versions of ourselves. Sonic spirituality, then, might be characterized as open instead of closed, exploratory and experimental rather than static. Eminem’s spiritual themes play out in terms of solidarity with the supernatural, a mistrust of organized religion due to its inherent hypocrisy, a desire for redemption from guilt through purification, and an intense personal battle between love and hate. Following are two potent examples of what I’ve found in Eminem’s oeuvre from 2009’s Relapse: Refill, examples that showcase the development of his sonic spirituality over the decade since my grandfather first introduced it to me.

In “Beautiful” (2009), Eminem poses a powerful question: What would you think if you saw someone important, like a government official or celebrity, digging around in the trash? The answer: you’d probably think that this kind of behavior was suitable for beggars only and certainly not for yourself or someone very important. But this is exactly what the rapper does in “Beautiful.” He looks for himself, others, and their fallen world or Eden (aka Detroit, Michigan) and finds everyone and everything in the garbage. In this way, “Beautiful” is a lovely parable. As with any parable, its objective is to illustrate a moral or a spiritual lesson using a simple human relation. The lesson in this case is looking for something or someone that has been lost. In Eminem’s parable, there are seven ideas expressed about how to find what we have lost and develop our spiritual selves along the way: loss (the starting point of humanity’s spiritual condition), light (a force created through words), movement (standing in another person’s shoes), discovery (finding what’s lost in low places), salvation (anyone can be redeemed), connection (exchange traditional religion for a new culture of communication with the supernatural), and celebration (that everyone can be made beautiful again).

These seven images are evoked by the lyrics and music. The slow and deliberate beat invites listeners to connect the subject and object; the song and themselves, the song and the rapper. The release provided as Eminem sings the chorus doesn’t just change the course of the song, but converts the shared loss into an opportunity for discovery, salvation, connection and celebration. Just as the discovery begins, the drums suddenly increase in volume; the bass and guitar begin to cry out as a background harmony in a major key builds and adds to the intensity. The sounds remind us even if we choose to shield our eyes, we cannot shield our ears from the plight of our fellows and that this is a call to action, salvation and celebration. In “Beautiful” Eminem listeners become aware of others’ oppression while remembering that they are no stronger or more beautiful than anyone else. In this way listeners are engaged not just with the sounds, but also with the spirits of the people who produce them in active relationship.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NRF_H7dewWY

The experiences and encounters inherent in Eminem’s alternative spiritual portrait, “My Darling” (2009), still emphasize the same spiritual themes I pointed out earlier: personal struggles between light and darkness, finding a purpose in suffering, and seeing a connection between societal and supernatural powers. Only this time, the supernatural power belongs to the Devil. Yet, unlike other songs in which Eminem does battle with the Devil or suffers for his sins through eternal damnation, “My Darling” is about a soul living in hell on earth. In this way, “My Darling” is both a lamentation and a dark parable whose moral complements that of “Beautiful.” Eminem shares this moral in “My Darling” through six ideas about what happens when a person is losing his or her battle with the demons he or she carries inside. These ideas are uncertainty (never being sure about redemption), possession (selling one’s soul), darkness (force maintained by the absence of words), harm (effects of love turning to hate), wholeness (spiritual relationships based on labor and exchange rather than on salvation and forgiveness), and lament (mourning one’s losses of self and loved ones).

As in “Beautiful,” the lyrics and the music evoke spiritual elements. The song is set to a minor key, which communicates penitential lamentation, intimate conversation with the Devil, and echoes with sighs of disappointment, divorce and disillusion. Possession, darkness and harm are communicated through call and response between Eminem and the Devil, who hears and accepts Eminem’s invitation and appears in his mirror where he whispers seductively for Eminem to draw close. The increasing intensity and harm of the spiritual exchange between Mathers and the Devil is reflected in their verbal back-and-forth. Their “souls, minds and bodies” are increasingly connected as they exchange more and more words. And the words become more desperate and cruel. At the end of the song, Eminem submits. Listeners come to understand that Eminem and the Devil are one and whole as the Devil’s final solo becomes the pair’s solemn duet. The two have become one spirit through a relationship of exchange and possession.

The recurrence of spiritual themes in Eminem’s soundscape suggests that music is a way to communicate with the other who is both present and hidden. Sometimes the other is God. Sometimes the other is the Devil. Sometimes the other is other people. Sometimes the other is the other within. The tones, rhythmic patters, key changes, intensity and release patterns combine with Eminem’s lyrics to create an experience within which listeners can be still, in which their souls can take refuge, and the other can be encountered. However, though sonic spirituality exists in Eminem’s music, and rumors abound regarding his “born again” status, it cannot be argued that Eminem adheres to a particular religion. Rather, the sonic spiritual element suggests that Eminem communicates a genuine awareness of supernatural powers, guilt-redemption-purification and love-hate that allows him to relate to the world at large. In this way Eminem is one of many artists whose pop culture content carries a strong spiritual dimension that is sonic, confirming results of Chris Rojek’s study, entitled “Celebrity and Religion,” which argues that “celebrity culture is secular society’s rejoinder to the decline of religion and magic” (393).

“DJ Hero party – Eminem 2” by Flickr user monsieurlam, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0

As “Beautiful” and “My Darling” demonstrate, the spiritual reflections heard in Eminem’s music are not just harmonic, they are also discordant, revealing how conflicted we often are about ourselves and the supernatural. Just as Eminem walks with God in “Beautiful” and dances with the Devil in “My Darling,” audiences listening to his music are able to escape from their own worlds and find temporary refuge in sonic spirituality. This idea didn’t start with Eminem, or with the Judeo-Christian tradition, as many faiths across time and space utilize the power of music to evoke higher powers and acquire spiritual insight through prayers, storytelling, meditation, chanting, mantras, singing, silent vows, etc. But Eminem has added his own unique touch by using his personas Slim Shady and Marshall Mathers to speak with demonic and godly authority, respectively. As Peter Ward writes in Gods Behaving Badly, the spiritual power of Eminem’s music for audiences lies in its representations of a “conflicted and complex self clothed in the metaphors of the divine and reflected back to us” (107). In other words, sonic spirituality is about engaging with something beyond the world around us while grappling with the personas and situations into which we’re immersed. As the music plays we are challenged to develop a listening heart.

The popularity of Eminem’s music supports the conclusion that his brand of sonic spirituality is set to the same rhythm as the hearts of fans that buy and listen to his messages. But his work can also speak to those who consider themselves spiritually committed, even if that commitment is often not manifested in traditional religious activities. In this way the dynamic nature of sonic spirituality manifests as a way of listening that allows for communication and communion through music and language. If the above is true, then we can take Eminem’s claim, expressed via tweet, that “music has the power to heal” as a spiritual declaration. And we can also take a fan’s response to this tweet as an Amen: “All Eminem songs has [sic] a spiritual connection… you have to have the ear to find that for yourself.”

—

Featured Image: “Slim Shady” by Flickr user Walt Jabasco, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

—

Marcia Alesan Dawkins, PhD is an award-winning writer, speaker, educator, and lecturer at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. She is the author of Clearly Invisible: Racial Passing and the Color of Cultural Identity (Baylor UP, 2012) and Eminem: The Real Slim Shady (Praeger, 2013).

Marcia writes about racial passing, mixed race identities, media, popular culture, religion and politics for a variety of high-profile publications. She earned her PhD in communication from USC Annenberg, her master’s degrees in humanities from USC and NYU and her bachelor’s degrees in communication arts and honors from Villanova. Contact: www.marciadawkins.com

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

The Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show and the Soundtrack of Desire–Marcia Alesan Dawkins

Love and Hip Hop: (Re)Gendering The Debate Over Hip Hop Studies–-Travis Gosa

“I Love to Praise His Name”: Shouting as Feminine Disruption, Public Ecstasy, and Audio-Visual Pleasure—Shakira Holt

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

- Finding Resonance, Finding María Lugones

- Press Play and Lean Back: Passive Listening and Platform Power on Nintendo’s Music Streaming Service

- “A Long, Strange Trip”: An Engineer’s Journey Through FM College Radio

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments