Re-orienting Sound Studies’ Aural Fixation: Christine Sun Kim’s “Subjective Loudness”

Editors’ note: As an interdisciplinary field, sound studies is unique in its scope—under its purview we find the science of acoustics, cultural representation through the auditory, and, to perhaps mis-paraphrase Donna Haraway, emergent ontologies. Not only are we able to see how sound impacts the physical world, but how that impact plays out in bodies and cultural tropes. Most importantly, we are able to imagine new ways of describing, adapting, and revising the aural into aspirant, liberatory ontologies. The essays in this series all aim to push what we know a bit, to question our own knowledges and see where we might be headed. In this series, co-edited by Airek Beauchamp and Jennifer Stoever you will find new takes on sound and embodiment, cultural expression, and what it means to hear. –AB

Editors’ note: As an interdisciplinary field, sound studies is unique in its scope—under its purview we find the science of acoustics, cultural representation through the auditory, and, to perhaps mis-paraphrase Donna Haraway, emergent ontologies. Not only are we able to see how sound impacts the physical world, but how that impact plays out in bodies and cultural tropes. Most importantly, we are able to imagine new ways of describing, adapting, and revising the aural into aspirant, liberatory ontologies. The essays in this series all aim to push what we know a bit, to question our own knowledges and see where we might be headed. In this series, co-edited by Airek Beauchamp and Jennifer Stoever you will find new takes on sound and embodiment, cultural expression, and what it means to hear. –AB

—

A stage full of opera performers stands, silent, looking eager and exhilarated, matching their expressions to the word that appears on the iPad in front of them. As the word “excited” dissolves from the iPad screen, the next emotion, “sad” appears and the performers’ expressions shift from enthusiastic to solemn and downcast to visually represent the word on the screen. The “singers” are performing in Christine Sun Kim’s conceptual sound artistic performance entitled, Face Opera.

The singers do not use audible voices for their dramatic interpretation, as they would in a conventional opera, but rather use their faces to convey meaning and emotion keyed to the text that appears on the iPad in front of them. Challenging the traditional notions of dramatic interpretation, as well as the concepts of who is considered a singer and what it means to sing, this art performance is just one way Kim calls into question the nature of sound and our relationship to it.

Audible sound is, of course, essential to sound studies though sound itself is not audist, as it can be experienced in a multitude of ways. The contemporary multi-modal turn in sound studies enables ways to theorize how more bodies can experience sound, including audible sound, motion, vibration, and visuals. All humans are somewhere on a spectrum between enabled and disabled and between hearing and deaf. As we grow older most people move farther toward the disabled and deaf ends of the spectrum. In order to experience sound for a lifetime, it is imperative to explore multi-modal ways of experiencing sound. For instance, the Deaf community rejects the term disabled, yet realizes it is actually normative constructs of hearing, sound, and music that disable Deaf people. But, as Kim demonstrates, Deaf people engage with sound all of the time. In this case, Deaf individuals are not disabled but rather, what I identify as difabled (differently-abled) in their relationship with sound. While this term is not yet used in disability scholarship, it is not completely unique, as there is a Difabled Twitter page dedicated to, “Ameliorating inclusion in technology, business and society.” Rejection of the word disabled inspires me to adopt difabled to challenge the cultural binary of ability and embrace a more multi-modal approach.

Kim’s art explores sound in a variety of modalities to decenter hearing as the only, or even primary, way to experience sound. A conceptual sound artist who was born profoundly deaf, Kim describes her move into the sound artistic landscape: “In the back of my mind, I’ve always felt that sound was your thing, a hearing person’s thing. And sound is so powerful that it could either disempower me and my artwork or it could empower me. I chose to be empowered.”

For sound to empower, however, cultural perception has to move beyond the ear – a move that sound studies is uniquely poised to enable. Using Kim’s art as a guide, I investigate potential places for Deaf within sound studies. I ask if there are alternative ways to listen in a field devoted to sound. Bridging sound studies and Deaf studies it is possible to see that sound is not ableist and audist, but sound studies traditionally has suffered from an aural fixation, a fetishization of hearing as the best or only way to experience sound.

Pushing beyond the understanding of hearing as the primary (or only) sound precept, some scholars have begun to recognize the centrality of the body’s senses in sound experience. For instance, in his research on reggae, Julian Henriques coined the term sonic dominance to refer to sound that is not just heard but that “pervades, or even invades the body” (9). This experience renders the sound experience as tactile, felt within the body. Anne Cranny-Francis, who writes on multi-modal literacies, describes the intimate relationship between hearing and sound, believing that “sound literally touches us,” This process of listening is described as an embodied experience that is “intimate” and “visceral.” Steph Ceraso calls this multi-modal listening. By opening up the body to listen in multi-modal ways, full-bodied, multi-sense experiences of sound are possible. Anthropologist Roshanak Kheshti believes that the differentiation of our senses created a division of labor for our senses – a colonizing process that maximizes the use-value and profit of each individual sense. She reminds her audience that “sound is experienced (felt) by the whole body intertwining what is heard by the ears with what is felt on the flesh, tasted on the tongue, and imagined in the psyche” (714), a process she calls touch listening.

Other scholars continue to advocate for a place for the body in sound studies. For instance, according to Nina Sun Eidsheim, in Sensing Sound, sound allows us to posit questions about objectivity and reality (1), as posed in the age-old question, “If a tree falls in the forest and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?” Eidsheim challenges the notion of a sound, particularly music, as fixed by exploring multiple ways sound may be sensed within the body. Airek Beauchamp, through his notion of sonic tremblings, detaches sound from the realm of the static by returning to the materiality of the body as a site of dynamic processes and experiences that “engages with the world via a series of shimmers and impulses.” Understanding the body as a place of engagement rather than censorship, Cara Lynne Cardinale calls for a critical practice of look-listening that reconceptualizes the modalities of the tongue and hands.

Vibrant Vibrations by Flickr User The Manic Macrographer (CC BY 2.0)

As these scholars have identified, privileging audible sound over other senses reinforces normative ideas of communication and presumes that individuals hear, speak, and experience sound in normative ways. These ableist and audist rhetorics are particularly harmful for individuals who are Deaf. Deaf community members actively resist these ableist and audist assumptions to show that sound is not just for hearing. Kim identifies as part of the Deaf community and uses her art to challenge the ableist and audist ideologies of the sound experience. Through exploring one of Christine Sun Kim’s performance pieces, Subjective Loudness, I argue that we can conceptualize sound studies in the absence of auditory sound through the two concepts Kim’s piece were named for, subjectivity and loudness.

In creating Subjective Loudness, Kim asked 200 Tokyo residents to help her create a musical score. Hearing participants were asked to use their bodies to replicate sounds of common 85 dB noises into microphones. The sounds Kim selected included: the swishing of a washing machine, the repetitive rotation of printing press, the chaos of a loud urban street, and the harsh static of a food blender. After the list was complete, Kim has the sounds translated into a musical score, sung by four of Kim’s closest friends. The noises then become music, which Kim lowers below normal human hearing range for a vibratory experience accessible to hearing and non-hearing individuals alike; The result is music that is not heard but rather felt. As vibrations shake the walls, windows, and furniture audience members feel the music.

Kim’s performance expands upon current understandings of the body in sound by incorporating multiple materialities of sound into one experience. Rather than simply looking at an existing sound in a new way, she develops and executes the sound experience for her participants. Kim types the names of common 85 dB sounds, what most hearing people may call “noise” on an iPad – a visual representation of the sound.

By asking participants to use their bodies to replicate these sounds – to change words into noise – Kim moves visual representation moves into the audible domain. This phase is contingent on each participant’s subjective experience with the particular sound, yet it also relies on the materiality of the human body to be able to replicate complex sounds. The audible sounds were then returned to a visual state as they were translated into a musical score. In this phase, noise is silenced as it is placed as musical notes on a page. The score is then sung, audibly, once again shifting visual into audible. Noise becomes music.

Yet even in the absence of hearing the performers sing, observers can see and perhaps feel the performance. Similar to Kim’s Face Opera, this performance is not just for the ear. The music is then silenced by reducing its volume beyond that of normal hearing range. Vibrations surround the participants for a tactile experience of sound. But participants aren’t just feeling the vibrations, they are instruments of vibration as well, exerting energy back into the space that then alters the sound experience for other bodies. The materiality of the body allows for a subjective experience of sound that Kim would not be able to as easily manipulate if she simply asked audience members to feel vibrations from a washing machine or printing press. But Kim doesn’t just tinker with the subjectivity of modality, she also plays with loudness.

Christine Sun Kim at Work, Image by Flickr User Joi Ito, (CC BY 2.0)

In this performance Kim creates a think interweaving of modalities. Part of this interplay involves challenging our understanding of loudness. For instance, participants recreate loud noises, but then the loud noise is reduced to silence as it is translated into a musical score. The volume has been dialed down, as has the intensity as the musical score isolates participates. The sound experience, as the score, is then sung, reconnecting the audience to a shared experience. Floating with the ebb and flow of the sound, participants are surrounded by sound, then removed from it, only to then be surrounded again. Finally, as the sound is reduced beyond hearing range, the vibrations are loud, not in volume but in intensity. The participants are enveloped in a sonorous envelope of sonic experience, one that is felt through and within the body. This performance combats a long-standing belief Kim had about her relationship with sound.

As a child, Kim was taught, “sound wasn’t a part of my life.” She recounted in a TED talk that her experience was like living in a foreign country, “blindly following its rules, behaviors, and norms.” But Kim recognized the similarities between sound and ASL. “In Deaf culture, movement is equivalent to sound,” Kim stated in the same talk. Equating music with ASL, Kim notes that neither a musical note nor an ASL sign represented on paper can fully capture what a music note or sign are. Kim uses a piano metaphor to make her point better understood to a hearing audience. “English is a linear language, as if one key is being pressed at a time. However, ASL is more like a chord, all ten fingers need to come down simultaneously to express a clear concept in ASL.” If one key were to change, the entire meaning would change. Subjective Loudness attempts to demonstrate this, as Kim moves visual to sound and back again before moving sound to vibration. Each one, individually, cannot capture the fullness of the word or musical note. Taken as a performative whole, however, it becomes easier to conceptualize vibration and movement as sound.

Christine Sun Kim speaking ASL, Image by Flickr User Joi Ito, (CC BY 2.0)

In Subjective Loudness, Kim’s performance has sonic dominance in the absence of hearing. “Sonic dominance,” Henriques writes, “is stuff and guts…[I]t’s felt over the entire surface of the skin. The bass line beats on your chest, vibrating the flesh, playing on the bone, and resonating in the genitals” (58). As Kim’s audience placed hands on walls, reaching out to to feel the music, it is possible to see that Kim’s performance allowed for full-bodied experiences of sound – a process of touch listening. And finally, incorporating Deaf and hearing individuals in her performance, Kim shows that all bodies can utilize multi-modal listening as a way to experience sound. Kim’s performances re-centers alternative ways of listening. Sound can be felt through vibration. Sound can be seen in visual representations such as ASL or visual art.

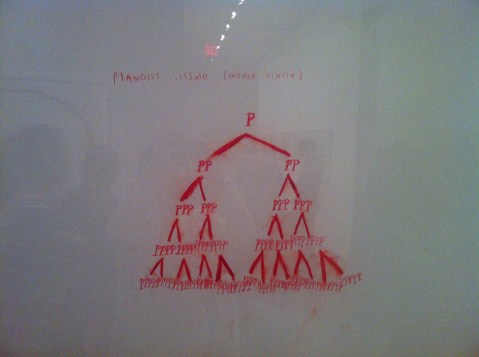

Image of Christine Sun Kim’s painting “Pianoiss….issmo” by Flickr User watashiwani (CC BY 2.0)

Through Subjective Loudness, it is possible to investigate subjectivity and loudness of sound experiences. Kim does not only explore sound represented in multi-modal ways, but weaves sound through the modalities, moving the audible to the visual to the tactile and often back again. This sound-play allows audiences to question current conceptions of sound, to explore sounds in multi-modalities, and to use our subjectivities in sharing our experiences of sound with others. Kim’s art performances are interactive by design because the materiality and subjectivity of bodies is what makes her art so powerful and recognizable. Toying with loudness as intensity, Kim challenges her audience to feel intensity in the absence of volume and spark the recognition that not all bodies experience sound in normative ways. Deaf bodies are vitally part of the soundscape, experiencing and producing sound. Kim’s work shows Deaf bodies as listening bodies, and amplifies the fact that Deaf bodies have something to say.

—

Featured image: Screen capture by Flickr User evan p. cordes, (CC BY 2.0)

—

Sarah Mayberry Scott is an Instructor of Communication Studies at Arkansas State University. Sarah is also a doctoral student in Communication and Rhetoric at the University of Memphis. Her current research focuses on disability and ableist rhetorics, specifically in d/Deafness. Her dissertation uses the work of Christine Sun Kim and other Deaf artists to explore the rhetoricity of d/Deaf sound performances and examine how those performances may continue to expand and diversify the sound studies and disability studies landscapes.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Introduction to Sound, Ability, and Emergence Forum –Airek Beauchamp

The Listening Body in Death— Denise Gill

Unlearning Black Sound in Black Artistry: Examining the Quiet in Solange’s A Seat At the Table — Kimberly Williams

Technological Interventions, or Between AUMI and Afrocuban Timba –Caleb Lázaro Moreno

“Sensing Voice”*–-Nina Sun Eidsheim

detritus 1 & 2 and V.F(i)n_1&2 : The Sounds and Images of Postnational Violence in Mexico

This April forum, Acts of Sonic Intervention, explores what we over here at Sounding Out! are calling “Sound Studies 2.0”–the movement of the field beyond the initial excitement for and indexing of sound toward new applications and challenges to the status quo.

This April forum, Acts of Sonic Intervention, explores what we over here at Sounding Out! are calling “Sound Studies 2.0”–the movement of the field beyond the initial excitement for and indexing of sound toward new applications and challenges to the status quo.

Two years ago at the first meeting of the European Sound Studies Association, I was inspired by the work of scholar and sound artist Linda O’Keeffe and her compelling application of the theories and methodologies of sound studies to immediate community issues. In what would later become a post for SO!, “(Sound)Walking Through Smithfield Square in Dublin,” O’Keeffe discussed her Smithfield Square project and how she taught local Dublin high school students field recording methodologies and then tasked them with documenting how they heard the space of the recently “refurbished” square and the displacement of their lives within it. For me, O’Keeffe’s ideas were electrifying, and I worked to enact a public praxis of my own via ReSounding Binghamton and the Binghamton Historical Soundwalk Project. Both are still in their initial stages; the work has been fascinating and rewarding, but arduous, slow, and uncharted. Acts of Sonic Intervention stems from my own hunger to hear more from scholars, artists, theorists, and/or practicioners to guide my efforts and to inspire others to take up this challenge. Given the exciting knowledge that the field has produced regarding sound and power (a good amount of it published here), can sound studies actually be a site for civic intervention, disruption, and resistance?

Last week, we heard from the Assistant Director at Binghamton University’s Center for Civic Engagement, Christie Zwahlen, who argues that any act of intervention must necessarily begin with self-reflexivity and examination of how one listens. In coming weeks, we will catch up with Linda O’Keeffe‘s newest project, a pilot workshop with older people at the U3A (University of the Third Age) centre in Foyle, Derry, “grounded in an examination of the digital divide, social inclusion and the formation of artists collectives.” We will also hear from artist, theorist, and writer Salomé Voegelin, who will treat us to a multimedia re-sonification of the keynote she gave at 2014’s Invisible Places, Sounding Cities conference in Viseu, Portugal, “Sound Art as Public Art,” which revivified the idea of the “civic” as a social responsibility enacted through sound and listening. This week, artist/scholar Luz María Sánchez gives us the privilege of a behind-the-scenes discussion of her latest work, detritus.2/ V.F(i)n_1–1st prize winner at the 2015 Biennial of the Frontiers in Matamoros, Mexico —which uses found recordings and images to break the deleterious silence created by narco violence in Mexico.

–JS, Editor-in-Chief

—

—

There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.

Walter Benjamin, Illuminations

detritus is an open-ended art project I started in 2011, that has as its main subject the portrayal of violence in Mexico. I introduce the sounds and images of what I call the Postnational Violence in Mexico using the concept of detritus as the nucleus; I use the cultural objects I produce through my artistic practice as the vehicle. detritus actually explores violence (1) as it is portrayed through media (radio, TV, newspapers and online platforms) and (2) as it is registered, manipulated and transmitted by the different participants of it –civilians, the government, NGOs, the military, the cartels–.

detritus

The first stage of detritus deals with Mexican media, specifically online newspapers, radio and TV, during the Presidency of Felipe Calderón (2006-2012). The whole strategy of [former] President Calderón —even before he took office— was to knock down violence associated to drug trafficking in Mexico and, actually, just a few days after he did his pledge as President of Mexico, he declared the war against drug trafficking that underwent from 11December 2006 —when Calderón actually started this war by sending 5,000 soldiers and police officers to the state of Michoacán— until the last day he was in Office: 31 November 2012.

During the six years that this war took place, former President Calderón appeared in military garments as “Mexico’s Drug War Commander in Chief.” The main target of this military strategy was to re-claim the control on those states where Mexican cartels were in charge. As Guillermo Pereyra argues in México: violencia criminal y “Guerra contra el narcotráfico” (2012), “Mexico’s Drug War” began as a decision to recover sovereignty in a context of political and social crisis. At the end of this period, there were more than 45,000 officers deployed in the states of Mexico, Baja California, Tamaulipas, Michoacán, Sinaloa and Durango, and more than 60,000 casualties. US media called this war “The Mexican War on Drugs” or “Mexico’s Drug War.”

The research for the visuals of detritus included every single [online] edition of Milenio and Jornada —Mexican national newspapers—from 11 December 2006 until 31 November 2012, and eventually it also included Proceso magazine and El Blog del Narco, an online independent news outlet. This research allowed me to investigate how the media has steadily been increasing the volume of news and images dealing with this war, therefore contributing to the “normalization” of the very violence it covers. As Colombian artist Doris Salcedo states the normalization of barbarism comes from the excessive number of deaths that violence is leaving to the society and, [I will add] to the excessive number of images and sounds that media and individuals put on circulation and make it viral through social networks and online independent outlets. All of us are, either as transmitters or as receivers, building this texture of violence.

The research for the visuals of detritus included every single [online] edition of Milenio and Jornada —Mexican national newspapers—from 11 December 2006 until 31 November 2012, and eventually it also included Proceso magazine and El Blog del Narco, an online independent news outlet. This research allowed me to investigate how the media has steadily been increasing the volume of news and images dealing with this war, therefore contributing to the “normalization” of the very violence it covers. As Colombian artist Doris Salcedo states the normalization of barbarism comes from the excessive number of deaths that violence is leaving to the society and, [I will add] to the excessive number of images and sounds that media and individuals put on circulation and make it viral through social networks and online independent outlets. All of us are, either as transmitters or as receivers, building this texture of violence.

At the end of 2013 detritus was completed: more than 10,200 images, all of them categorized in a database that includes: title of newspaper, section, header, author of the photograph, caption, and a brief description of the image itself. I used a very simple process of photographic manipulation to alter those 10,200 images. Once transformed, these images are projected, for a very short period of time [2 seconds each] in a large screen. We could be standing in front of this projection for hours and never see any of those images repeated. For those who are drawn to numbers, we could see that at the beginning of this war, during a whole weekend, there will be four or five images related to the subject; by the end of 2012, there were more than 40 images during the same period of time.

At the end of 2013 detritus was completed: more than 10,200 images, all of them categorized in a database that includes: title of newspaper, section, header, author of the photograph, caption, and a brief description of the image itself. I used a very simple process of photographic manipulation to alter those 10,200 images. Once transformed, these images are projected, for a very short period of time [2 seconds each] in a large screen. We could be standing in front of this projection for hours and never see any of those images repeated. For those who are drawn to numbers, we could see that at the beginning of this war, during a whole weekend, there will be four or five images related to the subject; by the end of 2012, there were more than 40 images during the same period of time.

detritus.2

But the description of the horror through Mexican media does not include all the necessary voices. That is why civilians started a process to empower themselves using the tools they have at hand–such as mobile phone’s cameras–a medium they can use without restrictions. Over the Internet, civilians circulated images, videos, and sounds of their day-to-day experiences dealing with extreme violence. They are not alone on this viralization of violence through audiovisual documents: members of drug cartels and self-defense groups are also uploading their combats. The big difference is each group’s “agenda.” Civilians are in search of an arena to share their experiences; cartels and other military groups are either in search of validation or in search of documenting the systematic violence used in order to control whole populations.

Therefore, the audio complement I designed for detritus, first detritus.2 and then its current iteration V.F(i)n_1 , features the sounds of shootings, recorded by civilians who happened to be at close range. Generally this footage was taken via mobile phone and uploaded onto YouTube, and, unlike the newspaper representations, the image is not necessarily what is most engaging, since the individual that is making the recording is usually at floor level, protected, in order to avoid being hit by a stray bullet. But the sounds are pristine: even if the image is almost motionless -in the corner of a room, looking through a small part of a window-, the sound describes better what is at stake: violence at a very close range. The sounds on these recordings are very similar: the shootings are placed in the background, and we generally listen to voices in the foreground.

Each of the twenty recordings that integrate to create detritus.2 was taken from You Tube. The shootings occurred in the cities of Nuevo Laredo, Reynosa, Zupango, Orizaba, Saltillo, Juarez, Changuitiro, Purépero, Xalapa, Jiquilpan, Santa María del Oro and Mexico City. All of them, played together, contribute to the assembly of what Salcedo calls a texture of sound. The recordings are reproduced/played by twenty portable digital speakers in the shape of guns. These sound-reproduction machines are completely autonomous–no power or sound cables attached–and each speaker is a sound component by itself. Once the battery is worn, the sound is gone until the battery is recharged, therefore restarting the process performance / sound – waste / silence. Silence is one of the worst problems when dealing with violence.The government and the drug cartels alike don’t want anybody to openly discuss these issues. Working with families within specific communities in Mexico and the US will help make their stories visible -out of the anonymous data- and visibility could empower them.

The Inferno

But exploring the “normalization” of violence through media is not my only intervention with detritus and detritus.2. Far from the sound art movement, where soundscape often functions as a neutral label that includes organized sounds taken from the surroundings, detritus.2 deals with Mexican contemporary cities’ sounds, recorded and disseminated by the same individuals that live within these acoustic situations. Those are the sounds that [also] construct the Mexican landscape, telling the story of the failed nation. Taken together, the sounds of detritus.2 amplifies the fact that we are standing in front of the failure of the Mexican state as we know it, and its civilian population has been dealing with this irregular situation for many decades. We have witnessed drug cartels infiltrate every layer of life; and just because many civilians end up surviving —with and around it—does not make the problem disappear. On the contrary, every broken boundary makes the problem harder and harder to be resolved.

The failure of the Mexican State, or the “inferno” as is being called now, is something Mexico can no longer hide. When I say Mexico here, I am not referring to its general population–already exhausted already from decades on “survival mode”– but rather the Capitol elite: the government, investors, intellectuals, and journalists alike. This situation is not new to civilians living outside of Mexico City. Entire communities in the north of Mexico have been abandoning their belongings-jobs-lives, in extremely fast exodus, either to the US or to tranquil states like Yucatán. Thousands of mothers and fathers are looking for their sons and daughters taken by the cartels, in the best-case scenario they are put to work as slaves either at the drug camps or as prostitutes, in the worst they may be in the thousands of mass graves that pollute the country. Civilians understood early in the story that any complaint to the police would result in an even worse situation. For years, it has been known in the bus industry that a lot of young male and female travelers have been kidnapped to make them join this industry of slaves, and only recently they started to admit it: tons of luggage at bus terminals on the northern states of Mexico speak for those that went missing, and nobody said a word. Just the past 19 October 2014 a corpse of a went-missing-police-officer’s mother was placed in front of the Ministry of the Interior’s building: they never pursued an investigation over the disappearance of the young officer, and the last will of this ailing mother was her coffin to be placed in the street outside of the Ministry of the Interior as a way of extreme protest.

The failure of the Mexican State, or the “inferno” as is being called now, is something Mexico can no longer hide. When I say Mexico here, I am not referring to its general population–already exhausted already from decades on “survival mode”– but rather the Capitol elite: the government, investors, intellectuals, and journalists alike. This situation is not new to civilians living outside of Mexico City. Entire communities in the north of Mexico have been abandoning their belongings-jobs-lives, in extremely fast exodus, either to the US or to tranquil states like Yucatán. Thousands of mothers and fathers are looking for their sons and daughters taken by the cartels, in the best-case scenario they are put to work as slaves either at the drug camps or as prostitutes, in the worst they may be in the thousands of mass graves that pollute the country. Civilians understood early in the story that any complaint to the police would result in an even worse situation. For years, it has been known in the bus industry that a lot of young male and female travelers have been kidnapped to make them join this industry of slaves, and only recently they started to admit it: tons of luggage at bus terminals on the northern states of Mexico speak for those that went missing, and nobody said a word. Just the past 19 October 2014 a corpse of a went-missing-police-officer’s mother was placed in front of the Ministry of the Interior’s building: they never pursued an investigation over the disappearance of the young officer, and the last will of this ailing mother was her coffin to be placed in the street outside of the Ministry of the Interior as a way of extreme protest.

Listening Ahead: V. (u)nF_2

In the next phase of detrius.2, V. (u)nF_2–an acronym for Vis. (un) necessary force–I am making sculptural objects and sounds to construct a multi-channel sound-installation exploring the question: how do civilians in Mexico live through the extreme violence product of the fight against drug cartels in a state that has revealed its own failure? The artwork consists of a multiple series of custom-made ceramic-sound devices/megaphones in the shape of human heads/faces, molded after living family members of civilians that are still on the “missing” lists, maybe kidnapped and/or killed by drug cartels. In order to make an archive that includes each family’s data, I will collaborate with organizations that assist civilians on finding their relatives. To make a representative selection, I plan to analyze data through a mathematic-algorithm; chosen families will be invited to be part of the project. Each family will designate a member to participate symbolically as the “missing” person. A 3D-scan data portrait will be made of each participant, followed by a ceramic-3D-print. I will then install an electronic-circuit and megaphone inside of the hollow-human-head/faces-ceramic-objects. To develop the sound element –a thick stratum of noise– I will digitally modify a multiple-layered-construction of sounds after the stored data. The specifics of each story/participant will be presented at the exhibition space through an interactive database. Custom-made ceramic-objects/megaphones will be resting on the floor; in in order to cross the exhibition-space, visitors will have to carefully move these 3D-ceramic-portraits, each one representing an individual story.

V. (u)nF_2 is a gesture that listens forward, taking those 24,000–and counting–missing-individuals outside of data-archives and rehumanizing them through storytelling, 3D-scan/print technology and sound. The fact that I will use traditional methods to approach my subject —the horror of this war against civilians– but will also use state-of-the-art-technology in order to shape the hardware needed for sound-installation, combines a human-scale project with the possibilities of the digital-world, which places this project within the so-called Third-Industrial-Revolution but grounds it in the real.

—

Listen to other sound installations by Luz María Sánchez:

Frecuencias Policiacas// Police Frequencies: “Las grabaciones que forman parte del audio multicanal de la instalación, fueron llevadas a cabo en la central de radiocomunicación de la policía de Nuevo Laredo, y fueron facilitadas a la artista por reporteros del diario El Mañana en agosto de 2005. Los audios registran una confrontación entre la policía de Nuevo Laredo y un grupo criminal no identificado, y por las características de los mismos, se pueden escuchar a diversos elementos policiacos, así como a las controladoras de la radiocomunicación. La re-transmisión de estos sonidos en una matriz multi-líneal, colocan a la obra en nuevos niveles de codificación en los que la complejidad visual, auditiva y político social de esta realidad, se hacen patentes.” –Description by Roberto Arcaute y Manuel Rocha Iturbide

Frecuencias Policiacas// Police Frequencies: “The recordings are part of the multichannel audio installation carried out in the central police radio Nuevo Laredo, provided to the artist by El Mañana newspaper reporters in August 2005. The audio recorded a confrontation between police and an unidentified criminal Nuevo Laredo group. . .The re-transmission of these sounds in a multi-linear matrix placed to work in new levels of encryption that make evident the social visual, auditory and political complexity of this reality.” –Description by Roberto Arcaute y Manuel Rocha Iturbide

2487: “2487 speaks the names of the two thousand four hundred eighty seven people who died crossing the U.S./Mexico border . The work employs digital technology and sound as a means for transborder memorialization and protest, imposing the absence of those lost into the public sphere. Sánchez’ immersive sound environment remaps social history as the names of the deceased fly across the border through soundscape and digital media. Drawing from data acquired from activist websites, Sánchez created a sound map of names which she recorded digitally. Her final score, along with the database, has been exhibited widely but lives permanently on the world wide web, in commemoration and quiet protest. Sánchez’ work connects the digital and geographic landscape to the listener’s body, gaining entry through sound and transcending political and physical barriers”– Description from UCR Critical Digital 8/19/2012

—

Sound and visual artist Luz María Sánchez studied both music and literature. Through her doctoral studies Sánchez has focused on the role of sound-in-art since its inception in the 19th century through its evolution as an independent art practice in the 20th century. Sánchez then examined the radio-plays of Samuel Beckett linking them to the sound-practices that emerged in the mid-20th century. Sánchez has continued her research on technologized-sound: she was part of the conference Mapping Sound and Urban Space in the Americas at Cornell University, and her book Technological Epiphanies: Samuel Beckett’s Use of Audiovisual Machines will be published in 2015. Her artwork has been included in major sound-and-music festivals such as Zéppellin-Sound-Art-Festival (Spain), Bourges-International-Festival-of-Electronic-Music-and-Sonic-Art (France), Festival-Internacional-de-Arte-Sonoro (Mexico), and has presented exhibitions at Marion-Koogler-McNay-Art-Museum, Dallas Center for Contemporary Art, Galería de la Raza (San Francisco), John-Michael-Kohler-Arts-Center (Sheboygan), Illinois State Museum (Chicago/Springfield), and Centro de Cultura Contemporánea (Barcelona) amongst others. She was granted a special distinction in the category Nouvea-Musiques at the Phonurgia-Nova-Prix (Arles), was the recipient of a Círculo-de-Bellas-Artes-de-Madrid’s grant, and Yuko Hasegawa selected her for the Artpace-International-Artist-in-Residence. She is member of the Board-of-the-Sound Experimentation-Space at Museum-of Contemporary-Art (MUAC). Sanchez was recently awarded the First Prize of the Frontiers Biennial (2015).

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“A Listening Mind: Sound Learning in a Literature Classroom”–Nicole Brittingham Furlonge

“Soundscapes of Narco Silence”—Marci R. McMahon

“Listening to the Border: ‘”2487″: Giving Voice in Diaspora’ and the Sound Art of Luz María Sánchez”-D. Ines Casillas

Recent Comments