SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests (Penn State University Press) is a book “about the sounds made by those seeking change” (5). It situates these sounds within a broader inquiry into rhetoric as sonic event and sonic action—forms of practice that are collective, embodied, and necessarily relational. It also addresses a long-standing question shared by many of us in rhetorical studies: Where did the sound go? And specifically, in a field that had centered at least half of its disciplinary identity around the oral/aural phenomena of speech, why did the study of sound and rhetoric require the rise of sound studies as a distinct field before it could regain traction?

Eckstein confronts this silence with urgency and clarity, offering a compelling case for how sound operates not just as a sensory experience but as a rhetorical force in public life. By analyzing protest environments where sound is both a tactic and a terrain of struggle, Sound Tactics reinvigorates our understanding of rhetoric’s embodied, affective, and spatial dimensions. What’s more, it serves as an important reminder that sound has always played an important role in studies of speech communication.

Rhetoric emerged in the Western tradition as the study and practice of persuasive speech. From Aristotle through his Greek predecessors and Roman successors, theorists recognized that democratic life required not just the ability to speak, but the ability to persuade. They developed taxonomies of effective strategies—structures, tropes, stylistic devices, and techniques—that citizens were expected to master if they hoped to argue convincingly in court, deliberate in the assembly, or perform in ceremonial life.

We’ve inherited this rhetorical tradition, though, as Eckstein notes early in Sound Tactics, in the academy it eventually splintered into two fields: one that continued to study rhetoric as speech, and another that focused on rhetoric as a writing practice. But somewhere along the way, even rhetoricians with a primary interest in speech moved toward textual representation of speech, rather than the embodied, oral/aural, sonic event that make up speech acts (see pgs 49-50).

Sound Tactics corrects this oversight first by broadening what counts as a “speech act”—not only individual enunciations, but also collective, coordinated noise. Eckstein then offers updated terminology and analytical tools for studying a wide range of sonic rhetorics. The book presents three chapter-length case studies that demonstrate these tools in action.

The first examines the digital soundbite or “cut-out” from X González’s protest speech following the school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. The second focuses on the rhythmic, call-and-response “heckling” by HU Resist during their occupation of a Howard University building in protest of a financial aid scandal. The third analyzes the noisy “Casseroles” retaliatory protests in Québec, where demonstrators banged pots and pans in response to Bill 78’s attempts to curtail public protest.

A full recounting of the book’s case studies isn’t possible here, but they are worth highlighting—not only for the issues Eckstein brings to light, but for how clearly they showcase his analytical tools and methods in action. These methods, in my estimation, are the book’s most significant contribution to rhetorical studies and to scholars more broadly interested in sound analysis.

Eckstein’s analytical focus is on what he calls the “sound tactic,” which is “the sound (adjective) use of sound (noun) in the act of demanding” (2). Soundness in this double sense is both effective and affective at the sensory level. It is rhetoric that both does and is sound work—and soundness can only be so within a particular social context. For Eckstein, soundness is “a holistic assessment of whether an argument is good or good for something” (14). Sound tactics, then, utilize a carefully curated set of rhetorical tools to accomplish specific argumentative ends within a particular social collective or audience capable of phronesis or sound practical judgement (16). Unsound tactics occur when sound ceases to resonate due to social disconnection and breakage within a sonic pathway (see Eckstein’s conclusion, where he analyzes Canadian COVID-19 protests that began with long-haul truck drivers, but lost soundness once it was detached from its original context and co-opted by the far right).

Just as rhetorical studies has benefitted from the influence of sound studies, Eckstein brings rhetorical methods to sound studies. He argues that rhetoric offers a grounding corrective to what he calls “the universalization of technical reason” or “the tendency to focus on the what for so long that we forget to attend to the why” (29). Following Robin James’s The Sonic Episteme: Acoustic Resonance, Neoliberalism, and Biopolitics, he argues that sound studies work can objectify and thus reify sound qua sound, whereas rhetoric’s speaker/audience orientation instead foregrounds sound as crafted composition—shaped by circumstance, structured by power, and animated by human agency. Eckstein finds in sound studies the terminology for such work, drawing together terms such as acousmatics, waveform, immediacy, immersion, and intensity to aid his rhetorical approach. Each name an aspect of the sonic ecology.

Rhetoricians often speak of the “rhetorical situation” or the circumstances that create the opportunity or exigence for rhetorical action and help to define the relationship between rhetor and audience. While the rhetorical action itself is typically concrete and recognizable, the situation itself—which is always in motion—is more difficult to pin down. “Acousmatics” names a similar phenomenon within a sonic landscape. Noise becomes signal as auditors recognize and respond to particular kinds of sound—a process that requires cultural knowledge, attention, and the proverbial ear to hear. A sound’s origins within that situation may be difficult to parse. Acousmastics accounts for sound’s situatedness (or situation-ness) within a diffuse media landscape where listeners discern signal-through-noise, and bring it together causally as a sound body, giving it shape, direction, and purchase. As such a “sound body” has a presence and power that a single auditor may not possess.

Eckstein defines “sound body” as “our imaginative response to auditory cues, painting vivid, often meaningful narratives when the source remains unseen or unknown” (10). And while the sound body is “unbounded,” it “conveys the immediacy, proximity, and urgency typically associated with a physical presence (12). Thus, a sound body (unlike the human bodies it contains) is unseen, but nonetheless contained within rhetorical situations, constitutive of the ways that power, agency, and constraint are distributed within a given rhetorical context. Eckstein’s sound body is thus distinct from recent work exploring the “vocal body” by Dolores Inés Casillas, Sebastian Ferrada, and Sara Hinojos in “The ‘Accent’ on Modern Family: Listening to Vocal Representations of the Latina Body” (2018, 63), though it might be nuanced and extended through engagement with the latter. A focus on the vocal body brings renewed attention to the materialities of the voice—“a person’s speech, such as perceived accent(s), intonation, speaking volume, and word choice” and thus to sonic elements of race, gender, and sexuality. These elements might have been more explicitly addressed and explored in Eckstein’s case studies.

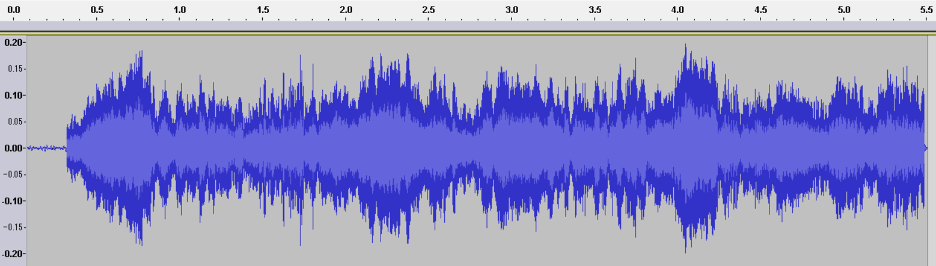

Eckstein uses these terms to help us understand the rhetorical complexities of social movements in our contemporary, digital world—movements that extend beyond the traditional public square into the diverse forms of activism made possible by the digital’s multiplicities. In that framework he offers the “waveform” as a guiding theoretical concept, useful for discerning the sound tactics of social movements. A waveform—the digital, visual representation of a sonic artifact—provides a model for understanding how sound takes shape, circulates, and exerts force. Waveforms also obscure a sound’s originating source and thus act acousmastically.

“[A] waveform is a visual representation of sound that measures vibration along three coordinates: amplitude, frequency, and time” (50). Eckstein draws on the waveform’s “crystallization” of a sonic moment as a metaphor to show sound’s transportability, reproducibility, and flexibility as a media object, and then develops a set of analytical tools for rhetorical analysis that match these coordinates: immediacy, immersion, and intensity. As he describes:

Immediacy involves the relationship between the time of a vibration’s start and end. In any perception of sound, there can be many different sounds starting and stopping, giving the potential for many other points of identification. Immersion encompasses vibration’s capacity to reverberate in space and impart a temporal signature that helps locate someone in an area; think of the difference between an echo in a canyon and the roar of a crowd when you’re in a stadium. Finally, intensity describes the pressure put on a listener to act. Intensity provides the feelings that underwrite the force to compel another to act. Each of these features and the corresponding impact of this experience offer rhetorical intervention potential for social movements. (51)

This toolset is, in my estimation, the book’s most cogent contribution for those working with or interested in sonic rhetorics. Eckstein’s case studies—which elucidate moments of resistance to both broad and incidental social problems—offer clear examples of how these interrelated aspects of the waveform might be brought to bear in the analysis of sound when utilized in both individual and collective acts of social resistance.

To highlight just one example from Eckstein’s three detailed case studies, consider the rhetorical use of immediacy in the chapter titled “The Cut-Out and the Parkland Kid.” The analysis centers on a speech delivered by X González, a survivor of the February 14, 2018, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida. Speaking at a gun control rally in Ft. Lauderdale six weeks after the tragedy, González employed the “cut-out,” a sound tactic that punctuated their testimony with silence.

Embed from Getty Images.

As the final speaker, González reflected on the students lost that day—students who would no longer know the day-to-day pleasures of friendship, education, and the promise of adulthood. The “cut-out” came directly after these remembrances: an extended silence that unsettled the expectations of a live audience disrupting the immediacy of such an event. As the crowd sat waiting, González remained resolute until finally breaking the silence: “Since the time that I came out here, it has been six minutes and twenty seconds […] The shooter has ceased shooting and will soon abandon his rifle, blend in with the students as they escape, and walk free for an hour before arrest” (69–70).

As Eckstein explains, González “needed a way to express how terrifying it was to hide while not knowing what was happening to their friends during a school shooting” (61). By timing the silence to match the duration of the shooting, the focus shifted from the speech itself to an embodied sense of time—an imaginary waveform of sorts that placed the audience inside the terror through what Eckstein calls “durational immediacy.” In this way, silence operated as a medium of memory, binding audience and victims together through shared exposure to the horrors wrought over a short period of time.

…

Sound Tactics is a must-read for those interested in a better understanding of sound’s rhetorical power—and especially how sonic means aid social movements. In conclusion, I would mention one minor limitation of Eckstein’s approach. As much as I appreciated his acknowledgement of sound’s absence from the Communication side of rhetoric, such a proclamation might have benefited from a more careful accounting of sound-related works in rhetorical studies writ large over the last few decades. Without that fuller context, readers may conclude that rhetorical studies has—with a few exceptions—not been engaged with sound. To be fair, the space and focus of Sound Tactics likely did not permit an extended literature review. There is thus an opportunity here to connect Eckstein’s important intervention with the work of other rhetoricians who have also been advancing sound studies.

I am including here a link to a robust (if incomplete) bibliography of sound-related scholarship that I and several colleagues have been compiling, one that reaches across Communication and Writing disciplines and beyond.

—

Featured Image: Family at the CLASSE (Coalition large de l’ASSÉ ) Demonstration in Montreal, Day 111 in 2012 by Flicker User scottmontreal CC BY-NC 2.0

—

Jonathan W. Stone is Associate Professor of Writing and Rhetoric at the University of Utah, where he also serves as Director of First-Year Writing. Stone studies writing and rhetoric as emergent from—and constitutive of—the mythologies that accompany notions of technological advance, with particular attention to sensory experience. His current research examines how the persisting mythos of the American Southwest shapes contemporary and historical efforts related to environmental protection, Indigenous sovereignty, and racial justice, with a focus on how these dynamics are felt, heard, and lived. This work informs a book project in progress, tentatively titled A Sense of Home.

Stone has long been engaged in research that theorizes the rhetorical affordances of sound. He has published on recorded sound’s influence in historical, cultural, and vernacular contexts, including folksongs, popular music, religious podcasts, and radio programs. His open-source, NEH-supported book, Listening to the Lomax Archive, was published in 2021 by the University of Michigan Press and investigates the sonic archive John and Alan Lomax created for the Library of Congress during the Great Depression. Stone is also co-editor, with Steph Ceraso, of the forthcoming collection Sensory Rhetorics: Sensation, Persuasion, and the Politics of Feeling (Penn State U Press), to be published in January 2026.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings –Vanessa Valdés

Quebec’s #casseroles: on participation, percussion and protest–-Jonathan Sterne

SO! Reads: Steph Ceraso’s Sounding Composition: Multimodal Pedagogies for Embodied Listening-–Airek Beauchamp

Faithful Listening: Notes Toward a Latinx Listening Methodology––Wanda Alarcón, Dolores Inés Casillas, Esther Díaz Martín, Sara Veronica Hinojos, and Cloe Gentile Reyes

The Sounds of Equality: Reciting Resilience, Singing Revolutions–Mukesh Kulriya

SO! Reads: Todd Craig’s “K for the Way”: DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies—DeVaughn Harris

Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

.

16 years in, we’re still here, listening hard for each thump, rasp, and rattle of the drum to amplify for our readers. Keep the pressure coming louder and louder for us to propagate, and look out for our print edition, Power in Listening: The Sounding Out! Reader to drop in August 2026 from NYU Press! –JS, Ed-in-Chief

Here, beginning with number 10, are our Top 10 posts released in 2025 (as of 12/13/25)!

—

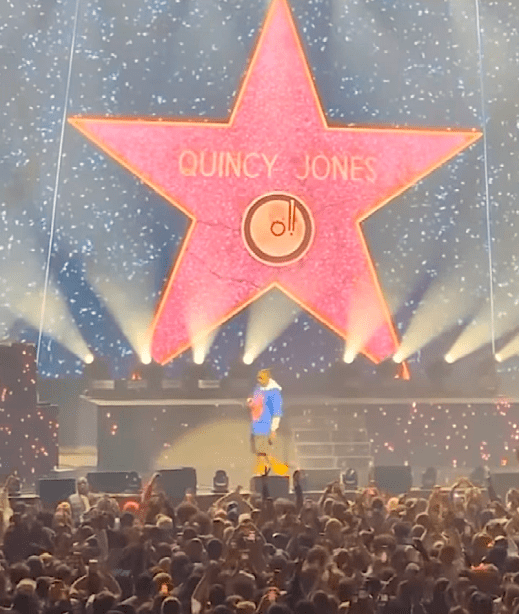

(10). The Sonic Rhetoric of Quincy Jones (feat. Nasir Jones)

By Jaquial Durham

“The passing of Quincy Jones has left a silence that feels almost impossible to fill. Every time I play Thriller at home now, it’s no longer just a celebration of his unparalleled artistry. It’s a ritual to sit with his legacy, listen more closely, and honor how his music shaped the sound of memory itself. With each spin of the record, my family and I find ourselves inside his arrangements, held by their richness, precision, and sense of story as though the music is breathing with us, speaking back across time. Jones’s work was never just production; it was communication. A language of sound connected us to melody and beat and the fuller spectrum of emotion, culture, and memory that lives in Black music.. .”

[Click here to read more]

—

(9). The Techno-Woman Warrior: K-pop and the Sound of Asian Futurism

By Hoon Lee

“As a ’90s kid, I remember too well us school kids singing and dancing to the songs at the top of the charts on music shows such as Ingigayo (인기가요) and Music Bank (뮤직뱅크). It was what one might call the “pre-K-pop” era: there were a lot of solo artists performing in various genres, and the notion of idol culture as we know it now was only fledgling. Without the mass production system or the global distribution that has come to be the norm in today’s K-pop, first generation idol groups around the new millennium—H.O.T., Fin.K.L, god, Sechs Kies, S.E.S.—not only set up these business models and standards, but also inspired the music and aesthetics of later generations. The group aespa’s cover of “Dreams Come True” by S.E.S. is an exemplar case, and NewJeans, with their unflinching Y2K aesthetics and sound, take us back to the millennial through and through. . .”

[Click here to read more]

—

(8).Finding Resonance, Finding María Lugones

By Daimys García

“I am always listening for María: I find her most in the traces of words.

Trained as a literary scholar, I relish in the contours of stories; I savor the nuances found between crevices of language and the shades of implication when those languages are strung together. It is no surprise, then, that since the death of my friend and mentor María Lugones, I have turned to many books, particularly her book, Pilgrimages/Peregrinajes: Theorizing Coalition Against Multiple Oppression, to feel connected to her. I have struggled, though, to write about her, talk about her, even think about her for many years. It wasn’t until I found a passage about spirits and hauntings in Cuban-American writer and artist Ana Menéndez’s novel The Apartment that I found language to describe a way through the grief of the last five years. . .”

[Click here to read more]

——

(7). The Sounds of Equality: Reciting Resilience, Singing Revolutions

by Mukesh Kulriya

“When the pandemic hit the world in late 2019, the concept of lockdown ceased the social life of the people and their communities. In these unprecedented circumstances, a video from Italy took the internet. People in Italian towns such as Siena, Benevento, Turin, and Rome were singing from their windows and balconies, which raised morale. The song “Bella Ciao,” an old partisan Italian song, became an anthem of hope against adversity. This anti-fascist song was popularized during the mid-20th century across the globe as a part of progressive movements. Following this, people in many countries around the world created their renditions of “Bella Ciao” in Turkish, Arabic, Kurdish, Persian, French, Spanish, Armenian, German, Portuguese, Russian, and within India in languages such as Punjabi, Marathi, Bangla, and even in sign language renditions. It was such an apt moment that captured the idea of empathy, solidarity, and the human need for community. This moment was still resonating with me when I was approached by Goethe Institut, New Delhi, to work on music and protest, and create The Music Library. I knew what I needed to do. . . .”

[Click here to read more]

—

(6).SO! Reads: Zeynep Bulut’s Building a Voice: Sound, Surface, Skin

—by Enikő Deptuch Vághy

“Voice and sound theorist Zeynep Bulut’s Building a Voice: Sound, Surface, Skin (Goldsmiths Press, 2025) is a remarkable work that reconfigures the ways we define “voice.” The text is organized into three sections—Part 1: Plastic (Emergence of Voice as Skin), Part 2: Electric (Embodiment of Voice as Skin), and Part 3: Haptic (Mediation of Voice as Skin)—each articulating Bulut’s exploration of the simultaneously personal and collaborative ways voice evolves among various sonic entities and environments. Through analyses of several artistic works that experiment with sound, Bulut successfully highlights the social effects of these pieces and how they alter our expectations of what it means to communicate and be understood.”

[Click here to read more]

—

(5). Clapping Back: Responses from Sound Studies to Censorship & Silencing

by MLA Sound Studies Executive Forum

“The MS Sound Forum invites papers for a guaranteed session at the Modern Language Association’s annual conference in Toronto, Canada in January 2026. The session responds in part to the MLA Executive Council’s refusal to allow debate or a vote on Resolution 2025-1, which supported the international “Boycott, Divest, and Sanction” (BDS) Movement for Palestinian rights against the ongoing genocide in Gaza. In light of the Council’s suppression of debate, some of the Sound Forum Executive Committee members decided to resign in protest while others remained to hold the MLA accountable for its undemocratic procedures. To acknowledge and respect the decision of those who left, the remaining members chose not to immediately fill the vacancies to let the parting members’ silence speak.. . .”

[Click here to read more]

—

—(4). “Just for a Few Hours, We Was Free”: The Blues and Mapping Freedom in Sinners (2025)

by Juston Burton

“In the 2025 blockbuster Sinners, Ryan Coogler has a vampire story to tell. But before he can begin, he needs to tell another story—a blues one. Sinners opens with a voiceover thesis statement performed by Wunmi Mosaku (who plays Annie in the film—more on her below) about the work the blues can do, then rambles the narrative through and around 1932 Clarksdale, eventually settling into a juke joint outside of town. Here, the blues story builds to a frenzied climax, ultimately conjuring the vampires propelling the film’s second half. It’s those vampires that most immediately register as cinematic spectacle, but Coogler’s impetus to film in IMAX and leverage all of his professional relationships for the movie wasn’t the monsters—it was to showcase the blues at a scale the music deserves. In Sinners, the blues takes center stage as a generative sonic practice, sound that creates space to be and to know in the crevices of the material world, providing passage between oppression and freedom, life and death, past and future, and good and evil. . .”

[Click here to read more]

—

—(3). “Keep it Weird”: Listening with Jonathan Sterne (1970-2025)

by Benjamin Tausig

“Dr. Jonathan Sterne passed away earlier this year. He was, in many ways, a model scholar and colleague.

The intellectual ferment of the field now called “sound studies” is often traced to the sonic ecologists of the 1960s, but the theoretical energy of the early 2000s, generated by figures such as Ana Maria Ochoa, Alexander Weheliye, Emily Thompson, Trevor Pinch (1952-2021), and of course Jonathan Sterne, was necessary for the field to gain interdisciplinary traction in the twenty-first century. Sterne’s The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (Duke University Press: 2003) was perhaps the single-most important book in this regard.

Trained in communications, and working in departments of communication, first at Pitt and later McGill, Sterne oriented his work toward media studies, and indeed, The Audible Past is principally about mediation. It poses questions about the role of sound in the history of mediation that earlier generations of sound studies had tended to elide, especially regarding the contingent and often cultural role of the human ear in reception. These questions opened the door for anthropologists, historians, communications scholars and ethnomusicologists in particular to think and even identify with sound studies, and many of us who were trained in the 2000s did so enthusiastically, with Sterne’s writing a lodestar.. . .”

[Click here to read more]

—

(2). Faithful Listening: Notes Toward a Latinx Listening Methodology

by Wanda Alarcón, Dolores Inés Casillas, Esther Díaz Martín, Sara Veronica Hinojos, Cloe Gentile Reyes

“For weeks, we have been inundated with executive orders (220 at last count), alarming budget cuts (from science and the arts to our national parks), stupendous tariff hikes, the defunding of DEI-anything, the banning of transgender troops, a Congressional renaming of the Gulf of Mexico, terrifying ICE raids, and sadly, a refreshed MAGA constituency with a reinvigorated anti-immigrant public sentiment. Worse, the handlers for the White House’s social media publish sinister MAGA-directed memes, GIFs across their social channels. These reputed Public Service Announcements (PSAs), under President Trump’s second term, ruthlessly go after immigrants.

It’s difficult to refuse to listen despite our best attempts.. . .”

[Click here to read more]

—

(1). SO! Podcast #82: Living Sounds: Rhythms of Belonging

“CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD: SO! Podcast #82: Living Sounds: Rhythms of Belonging

SUBSCRIBE TO THE SERIES VIA APPLE PODCASTS

FOR TRANSCRIPT: ACCESS EPISODE THROUGH APPLE PODCASTS , locate the episode and click on the three dots to the far right. Click on “view transcript.”

It’s been a minute for the SO! podcast but we are glad to be back–however intermittently–with a podcast episode that shares a discussion between women sound studies artists and scholars. The panel “Living Sounds: Rhythms of Belonging,” was held on September 19 at 6-7pm EDT at The Soil Factory arts space in Ithaca, New York. Moderator Jennifer Lynn Stoever, sound studies scholar and our Ed. in Chief, talks with four women sound artists about their praxis: Marlo de Lara, Bonnie Han Jones, Sarah Nance and Paulina Velazquez Solis.. . .”

[Click here to read more]

—

Featured Image: “microphone on the bass drum of the drummer for No Age” by Flickr User Dan MacHold CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2024

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2023!

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2020-2022!

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2019!

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2018!

The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2017!

Recent Comments