Re-orienting Sound Studies’ Aural Fixation: Christine Sun Kim’s “Subjective Loudness”

Editors’ note: As an interdisciplinary field, sound studies is unique in its scope—under its purview we find the science of acoustics, cultural representation through the auditory, and, to perhaps mis-paraphrase Donna Haraway, emergent ontologies. Not only are we able to see how sound impacts the physical world, but how that impact plays out in bodies and cultural tropes. Most importantly, we are able to imagine new ways of describing, adapting, and revising the aural into aspirant, liberatory ontologies. The essays in this series all aim to push what we know a bit, to question our own knowledges and see where we might be headed. In this series, co-edited by Airek Beauchamp and Jennifer Stoever you will find new takes on sound and embodiment, cultural expression, and what it means to hear. –AB

Editors’ note: As an interdisciplinary field, sound studies is unique in its scope—under its purview we find the science of acoustics, cultural representation through the auditory, and, to perhaps mis-paraphrase Donna Haraway, emergent ontologies. Not only are we able to see how sound impacts the physical world, but how that impact plays out in bodies and cultural tropes. Most importantly, we are able to imagine new ways of describing, adapting, and revising the aural into aspirant, liberatory ontologies. The essays in this series all aim to push what we know a bit, to question our own knowledges and see where we might be headed. In this series, co-edited by Airek Beauchamp and Jennifer Stoever you will find new takes on sound and embodiment, cultural expression, and what it means to hear. –AB

—

A stage full of opera performers stands, silent, looking eager and exhilarated, matching their expressions to the word that appears on the iPad in front of them. As the word “excited” dissolves from the iPad screen, the next emotion, “sad” appears and the performers’ expressions shift from enthusiastic to solemn and downcast to visually represent the word on the screen. The “singers” are performing in Christine Sun Kim’s conceptual sound artistic performance entitled, Face Opera.

The singers do not use audible voices for their dramatic interpretation, as they would in a conventional opera, but rather use their faces to convey meaning and emotion keyed to the text that appears on the iPad in front of them. Challenging the traditional notions of dramatic interpretation, as well as the concepts of who is considered a singer and what it means to sing, this art performance is just one way Kim calls into question the nature of sound and our relationship to it.

Audible sound is, of course, essential to sound studies though sound itself is not audist, as it can be experienced in a multitude of ways. The contemporary multi-modal turn in sound studies enables ways to theorize how more bodies can experience sound, including audible sound, motion, vibration, and visuals. All humans are somewhere on a spectrum between enabled and disabled and between hearing and deaf. As we grow older most people move farther toward the disabled and deaf ends of the spectrum. In order to experience sound for a lifetime, it is imperative to explore multi-modal ways of experiencing sound. For instance, the Deaf community rejects the term disabled, yet realizes it is actually normative constructs of hearing, sound, and music that disable Deaf people. But, as Kim demonstrates, Deaf people engage with sound all of the time. In this case, Deaf individuals are not disabled but rather, what I identify as difabled (differently-abled) in their relationship with sound. While this term is not yet used in disability scholarship, it is not completely unique, as there is a Difabled Twitter page dedicated to, “Ameliorating inclusion in technology, business and society.” Rejection of the word disabled inspires me to adopt difabled to challenge the cultural binary of ability and embrace a more multi-modal approach.

Kim’s art explores sound in a variety of modalities to decenter hearing as the only, or even primary, way to experience sound. A conceptual sound artist who was born profoundly deaf, Kim describes her move into the sound artistic landscape: “In the back of my mind, I’ve always felt that sound was your thing, a hearing person’s thing. And sound is so powerful that it could either disempower me and my artwork or it could empower me. I chose to be empowered.”

For sound to empower, however, cultural perception has to move beyond the ear – a move that sound studies is uniquely poised to enable. Using Kim’s art as a guide, I investigate potential places for Deaf within sound studies. I ask if there are alternative ways to listen in a field devoted to sound. Bridging sound studies and Deaf studies it is possible to see that sound is not ableist and audist, but sound studies traditionally has suffered from an aural fixation, a fetishization of hearing as the best or only way to experience sound.

Pushing beyond the understanding of hearing as the primary (or only) sound precept, some scholars have begun to recognize the centrality of the body’s senses in sound experience. For instance, in his research on reggae, Julian Henriques coined the term sonic dominance to refer to sound that is not just heard but that “pervades, or even invades the body” (9). This experience renders the sound experience as tactile, felt within the body. Anne Cranny-Francis, who writes on multi-modal literacies, describes the intimate relationship between hearing and sound, believing that “sound literally touches us,” This process of listening is described as an embodied experience that is “intimate” and “visceral.” Steph Ceraso calls this multi-modal listening. By opening up the body to listen in multi-modal ways, full-bodied, multi-sense experiences of sound are possible. Anthropologist Roshanak Kheshti believes that the differentiation of our senses created a division of labor for our senses – a colonizing process that maximizes the use-value and profit of each individual sense. She reminds her audience that “sound is experienced (felt) by the whole body intertwining what is heard by the ears with what is felt on the flesh, tasted on the tongue, and imagined in the psyche” (714), a process she calls touch listening.

Other scholars continue to advocate for a place for the body in sound studies. For instance, according to Nina Sun Eidsheim, in Sensing Sound, sound allows us to posit questions about objectivity and reality (1), as posed in the age-old question, “If a tree falls in the forest and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?” Eidsheim challenges the notion of a sound, particularly music, as fixed by exploring multiple ways sound may be sensed within the body. Airek Beauchamp, through his notion of sonic tremblings, detaches sound from the realm of the static by returning to the materiality of the body as a site of dynamic processes and experiences that “engages with the world via a series of shimmers and impulses.” Understanding the body as a place of engagement rather than censorship, Cara Lynne Cardinale calls for a critical practice of look-listening that reconceptualizes the modalities of the tongue and hands.

Vibrant Vibrations by Flickr User The Manic Macrographer (CC BY 2.0)

As these scholars have identified, privileging audible sound over other senses reinforces normative ideas of communication and presumes that individuals hear, speak, and experience sound in normative ways. These ableist and audist rhetorics are particularly harmful for individuals who are Deaf. Deaf community members actively resist these ableist and audist assumptions to show that sound is not just for hearing. Kim identifies as part of the Deaf community and uses her art to challenge the ableist and audist ideologies of the sound experience. Through exploring one of Christine Sun Kim’s performance pieces, Subjective Loudness, I argue that we can conceptualize sound studies in the absence of auditory sound through the two concepts Kim’s piece were named for, subjectivity and loudness.

In creating Subjective Loudness, Kim asked 200 Tokyo residents to help her create a musical score. Hearing participants were asked to use their bodies to replicate sounds of common 85 dB noises into microphones. The sounds Kim selected included: the swishing of a washing machine, the repetitive rotation of printing press, the chaos of a loud urban street, and the harsh static of a food blender. After the list was complete, Kim has the sounds translated into a musical score, sung by four of Kim’s closest friends. The noises then become music, which Kim lowers below normal human hearing range for a vibratory experience accessible to hearing and non-hearing individuals alike; The result is music that is not heard but rather felt. As vibrations shake the walls, windows, and furniture audience members feel the music.

Kim’s performance expands upon current understandings of the body in sound by incorporating multiple materialities of sound into one experience. Rather than simply looking at an existing sound in a new way, she develops and executes the sound experience for her participants. Kim types the names of common 85 dB sounds, what most hearing people may call “noise” on an iPad – a visual representation of the sound.

By asking participants to use their bodies to replicate these sounds – to change words into noise – Kim moves visual representation moves into the audible domain. This phase is contingent on each participant’s subjective experience with the particular sound, yet it also relies on the materiality of the human body to be able to replicate complex sounds. The audible sounds were then returned to a visual state as they were translated into a musical score. In this phase, noise is silenced as it is placed as musical notes on a page. The score is then sung, audibly, once again shifting visual into audible. Noise becomes music.

Yet even in the absence of hearing the performers sing, observers can see and perhaps feel the performance. Similar to Kim’s Face Opera, this performance is not just for the ear. The music is then silenced by reducing its volume beyond that of normal hearing range. Vibrations surround the participants for a tactile experience of sound. But participants aren’t just feeling the vibrations, they are instruments of vibration as well, exerting energy back into the space that then alters the sound experience for other bodies. The materiality of the body allows for a subjective experience of sound that Kim would not be able to as easily manipulate if she simply asked audience members to feel vibrations from a washing machine or printing press. But Kim doesn’t just tinker with the subjectivity of modality, she also plays with loudness.

Christine Sun Kim at Work, Image by Flickr User Joi Ito, (CC BY 2.0)

In this performance Kim creates a think interweaving of modalities. Part of this interplay involves challenging our understanding of loudness. For instance, participants recreate loud noises, but then the loud noise is reduced to silence as it is translated into a musical score. The volume has been dialed down, as has the intensity as the musical score isolates participates. The sound experience, as the score, is then sung, reconnecting the audience to a shared experience. Floating with the ebb and flow of the sound, participants are surrounded by sound, then removed from it, only to then be surrounded again. Finally, as the sound is reduced beyond hearing range, the vibrations are loud, not in volume but in intensity. The participants are enveloped in a sonorous envelope of sonic experience, one that is felt through and within the body. This performance combats a long-standing belief Kim had about her relationship with sound.

As a child, Kim was taught, “sound wasn’t a part of my life.” She recounted in a TED talk that her experience was like living in a foreign country, “blindly following its rules, behaviors, and norms.” But Kim recognized the similarities between sound and ASL. “In Deaf culture, movement is equivalent to sound,” Kim stated in the same talk. Equating music with ASL, Kim notes that neither a musical note nor an ASL sign represented on paper can fully capture what a music note or sign are. Kim uses a piano metaphor to make her point better understood to a hearing audience. “English is a linear language, as if one key is being pressed at a time. However, ASL is more like a chord, all ten fingers need to come down simultaneously to express a clear concept in ASL.” If one key were to change, the entire meaning would change. Subjective Loudness attempts to demonstrate this, as Kim moves visual to sound and back again before moving sound to vibration. Each one, individually, cannot capture the fullness of the word or musical note. Taken as a performative whole, however, it becomes easier to conceptualize vibration and movement as sound.

Christine Sun Kim speaking ASL, Image by Flickr User Joi Ito, (CC BY 2.0)

In Subjective Loudness, Kim’s performance has sonic dominance in the absence of hearing. “Sonic dominance,” Henriques writes, “is stuff and guts…[I]t’s felt over the entire surface of the skin. The bass line beats on your chest, vibrating the flesh, playing on the bone, and resonating in the genitals” (58). As Kim’s audience placed hands on walls, reaching out to to feel the music, it is possible to see that Kim’s performance allowed for full-bodied experiences of sound – a process of touch listening. And finally, incorporating Deaf and hearing individuals in her performance, Kim shows that all bodies can utilize multi-modal listening as a way to experience sound. Kim’s performances re-centers alternative ways of listening. Sound can be felt through vibration. Sound can be seen in visual representations such as ASL or visual art.

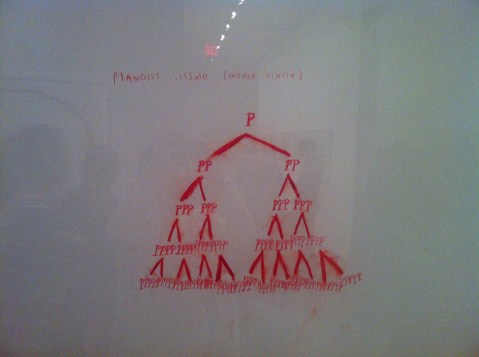

Image of Christine Sun Kim’s painting “Pianoiss….issmo” by Flickr User watashiwani (CC BY 2.0)

Through Subjective Loudness, it is possible to investigate subjectivity and loudness of sound experiences. Kim does not only explore sound represented in multi-modal ways, but weaves sound through the modalities, moving the audible to the visual to the tactile and often back again. This sound-play allows audiences to question current conceptions of sound, to explore sounds in multi-modalities, and to use our subjectivities in sharing our experiences of sound with others. Kim’s art performances are interactive by design because the materiality and subjectivity of bodies is what makes her art so powerful and recognizable. Toying with loudness as intensity, Kim challenges her audience to feel intensity in the absence of volume and spark the recognition that not all bodies experience sound in normative ways. Deaf bodies are vitally part of the soundscape, experiencing and producing sound. Kim’s work shows Deaf bodies as listening bodies, and amplifies the fact that Deaf bodies have something to say.

—

Featured image: Screen capture by Flickr User evan p. cordes, (CC BY 2.0)

—

Sarah Mayberry Scott is an Instructor of Communication Studies at Arkansas State University. Sarah is also a doctoral student in Communication and Rhetoric at the University of Memphis. Her current research focuses on disability and ableist rhetorics, specifically in d/Deafness. Her dissertation uses the work of Christine Sun Kim and other Deaf artists to explore the rhetoricity of d/Deaf sound performances and examine how those performances may continue to expand and diversify the sound studies and disability studies landscapes.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Introduction to Sound, Ability, and Emergence Forum –Airek Beauchamp

The Listening Body in Death— Denise Gill

Unlearning Black Sound in Black Artistry: Examining the Quiet in Solange’s A Seat At the Table — Kimberly Williams

Technological Interventions, or Between AUMI and Afrocuban Timba –Caleb Lázaro Moreno

“Sensing Voice”*–-Nina Sun Eidsheim

Recent Comments