Music Video as Process: “Revitalize” by T-Rhyme

What is a music video, anyway? Historically dismissed by film theorists as cinematically flawed or by the public as mere promotional snippets, music videos didn’t used to get the credit they deserve as a serious artistic medium. In the 1990s, Carol Vernallis challenged both notions, suggesting that they are actually a unique genre where music and visuals aren’t just paired—they communicate deeply with each other. Since then, scholars have taken diverse approaches to try to make sense of how film theory is applicable to these delicious nuggets of musical storytelling. For example, Phoebe Macrossan argues that Beyoncé’s Lemonade is a signal example of “film worlding,” indicating how the artist uses video to create her own intimate and all-encompassing environment. Additionally, Olu Jenzen and colleagues have found that political remix videos use recombinations of existing sounds and images to make rhetorical points that can challenge mainstream media reporting in real time. According to Stan Hawkins and Tore Størvold, from the perspectives of musicology or music theory, perhaps it is the video that amplifies the song’s harmonic structure or musical form, as suggested by their analysis of Justin Timberlake’s “Man of the Woods.”

Through skillful harmonic analysis or rhetorical analysis or cataloging of film techniques, scholars and critics now take music videos seriously. Yet, across interdisciplinary research approaches to music videos, what is largely taken for granted is that the music video is an object, a work to which various theories can be applied. What if we extend these approaches further and consider the music video not just as an object of analysis to be dissected, but as a representation of a creative process that entwines sound and vision in innovative ways to connect people and forge relationships? Such an analysis is especially possible when listening to independent creators who take an active role in conceptualizing, shooting, and editing their videos. By shifting our perspective to view the music video as documenting an ongoing creative and relational journey rather than solely as an object for analysis, we open up new possibilities for understanding the deeper significance of these works. Music videos can serve not just as vehicles for artistic expression, but as catalysts for strengthening bonds, preserving cultural knowledge, and fostering a sense of pride and resilience within communities.

Music Video as Process

In 2023, I co-organized a series of performances for Native Jam Night at UC Riverside, an annual music showcase featuring Indigenous artists from California and across Turtle Island. One way my colleagues and I honed in on guest artists was by asking students to listen to several playlists and recommend the music that spoke to them. The song “Revitalize” by T-Rhyme came up as a favorite. T-Rhyme has released music that tells personal stories and responds to contemporary social realities. At times, this music responds to her lived experience as a woman with Nehiyaw and Denesuline roots.

The music video for “Revitalize” is not only a popular extension of the song’s appeal, but an audiovisual series of connections and interactions. Paying attention to it in this way shows what can emerge from one kind of nontraditional listening posture, this one inspired by my conversations with T-Rhyme and also grounded in the way I have been opening my ears to her music. I first got to know T-Rhyme in-person when I invited her and MC Eekwol to perform as part of the Show & Prove hip hop event in 2018. We stayed in touch over the next several years.

As part of T-Rhyme’s return visit to California in 2023, we got to drive around and talk music business, have dinner with Native directors and actors as part of an Indigenous Storytelling event, go shopping, and get tacos at one of my favorite hole-in-the-wall spots. When it came time to make plans around the release for my book Sonic Sovereignty: Hip Hop, Indigeneity, and Shifting Popular Music Mainstreams, I knew it made sense to keep building on dialogues with musicians. Instead of just talking about myself, or even ideas that were already published, I wanted to keep the conversation going, continue listening, and find ways to share what I was hearing with more audiences. When I talked with T-Rhyme in the winter and spring of this year, then, it was to hear more about her creative process beyond any single project, to talk about what I was hearing and how I was listening, and to make space for that meaning making that almost approaches a musical flow that can bubble up out of a good dialogue.

Revitalization

A years-long process led up to “Revitalize,” T-Rhyme told me, and there are goals for the song that stretch beyond the moment of recording. To make the video, T-Rhyme went out to ceremonial grounds with her family and her photographer cousin Tennille Campbell’s family, spending time out with buffalo so Campbell could record. Looking back, she went through over a year and a half of her recordings of family and friends to select moments of daily life to interweave with special moments of celebration.

To convey the importance of land with viewers, the rapper worked with her brother, who shared his drone landscape footage that he recorded where he lives in northern Saskatchewan. She filmed other pieces at a powwow in Treaty Six territory in Alberta, finding inspiration from old friends she reconnected with for the occasion, as well as other Indigenous musicians and dancers she met while looking to connect there. T-Rhyme delivers the chorus and rapped verses over a beat by Doc Blaze, while collaborators in the music video mouth key words, notably “revitalize,” to her audio. Each aspect of the video was made with family or friends, and together they encompass years of work and hopes for the future.

From her past work, T-Rhyme recalled that shooting a music video can be stressful and involve intense time pressure. Instead, she told me, “I wanted none of those vibes to be involved with this project. I wanted the whole entire thing to be good vibes. And positive because part of our healing is through laughter and joking and being together as family.”

So, what is “revitalization” in the context of making music with family and friends? For T-Rhyme, “These are people I trust, I grew with, I evolved with, I changed with. All these people make me feel good and that I’m proud of, that I want to show off.” Paying attention to how musicians choose to tell their stories and further relationships with others is part of recognizing their sovereignty through sound. Sonic sovereignty is an active process.

The notion of “sonic sovereignty” builds from Jolene Rickard’s determination in “Diversifying Sovereignty and the Reception of Indigenous Art,” that “the idea of our art serving Indigenous communities reinforced my understanding that sovereignty is more than a legal concept”(82), and Tewa and Dine scholar-filmmaker Beverly Singer’s working through what she refers to as “cultural sovereignty,” in Wiping the War Paint off the Lens: Native American Film and Video, “which involves trusting in the older ways and adapting them to our lives in the present”(2). It’s meaningful to move into celebration together, as T-Rhyme explains: “Part of revitalization, especially when it comes to our healing as Native people, is we need to remember love. We don’t need to be in survival mode all the time.”

Intergenerational Teaching

Generations of T-Rhyme’s family stretch throughout the video for “Revitalize”. In the first verse, the musician’s mother stands in a bright red ribbon skirt at the edge of the river, near a photo frame.Then this photo of the rapper’s grandparents smiles out from the rocky shores of a river. A kid in sneakers runs nimbly over these same rocks, generations converging at the water. When T-Rhyme raps in the chorus, “raise your fists high in the air right now,” viewers see her mother raising her fist, the river greenery behind her, then proudly holding the picture of her own parents.

Music videos are often associated with youth culture, especially in a North American context. Yet in process and in content, this music video showcases intergenerational teaching and learning, with the involvement of elders, parents, children, and friends, connecting embodied knowledge across generations. Men and boys teaching intergenerationally feature onscreen, notably a father and son in regalia and an entrepreneur who runs Cree Coffee Company. Community leaders and scholars across Turtle Island share stories of diverse Indigenous masculinities, highlighting the kinds of teaching, leadership, and care that men, boys, and masculine people share from the present into the future. T-Rhyme reflected, “we have men out here who are trying to be warriors still, in their own way, whether they’re dancing powwow, whether they’re running their own business, and just being present fathers.”

T-Rhyme described that over the years, her relationship with her mother has changed. And yet, they have an ongoing push and pull between being serious and being playful together. With her mom, she says, “laughter and joking is our medicine.” She laughed as she recalled that for filming, “we’d be trying to have a serious moment and I’d say ‘okay mom, stand in the water’ and she’d say, ‘okay, like this.’ ‘Yeah, that looks good. Rest your face. You look real Kookum right now.’ Just cracking jokes at her.” T-Rhyme uses a word for grandmother to kid with her mom.

The process of writing the lyrics, too, involved reflecting on the relationship she has had with her mom across the past, present, and future. T-Rhyme raps, “My mother is sacred, she’s a survivor for real, though it’s taken her and I so many decades to heal.” This comes from what the rapper describes as a way to highlight how her mom is a “survivor and somebody that I respect and ultimately, enabled and motivated me to do my own healing too.”

In the context of intergenerational healing, T-Rhyme’s music video, which involves multiple generations of her family, embodies Indigenous survivance –the active transition from mere survival to resilience—in the face of historical and ongoing colonial violence. T-Rhyme brought her grandparents into the filming through their photograph, and their living memory. She explained, “Without them, I wouldn’t be here, my kids wouldn’t be here and my mom wouldn’t be here. Speaking of revitalization, they were the ones that were the front lines of maintaining our culture through a literal, cultural genocide in our communities.” Since “they really had to do their part in maintaining our culture enough to survive through residential school,” she recalls, “It was important to me to acknowledge them as survivors.”

T-Rhyme included her daughter in ‘Revitalize,” as well as in other music videos, notably the title track on “For Women By Women.” She explains, “I always want to feature her because she’s such a powerhouse.” T-Rhyme’s visual narrative brings in a photo of her daughter dancing at one of her shows, and the rapper has made music videos with her son as well.

When they were all getting stir-crazy from COVID shutdowns, T-Rhyme and her kids made the video “Trap’d,” for which the rapper helped then-12-year-old Joaquem act as videographer. Teaching her son and daughter and giving them space to make their own art, she calls her kids her “heroes,” explaining, “I just love including them where I can.”

The Story Beyond the Video

Watching and listening to the work of independent artists, such as T-Rhyme, complements existing writing on music video that comments on mainstream names like Madonna and Beyoncé. Furthermore, approaching music videos as processes through which relationships are built and furthered rather than solely as objects for analysis invites other forms of listening, especially modes that acknowledge the network of people whose interactions create the sounds that vibrate audience members’ eardrums.

The people who click play on the finished music video make up what is traditionally understood as its audience. By witnessing relationships behind musical choices, we can recognize that there is another group, too, that the video is for: media professionals, family members, and community participants who work together to create it. Making a piece as complicated as a music video can become an occasion for all of these actors to further and strengthen relationships: filming may offer the excuse everyone needed to visit an important location together, or storyboarding brings people in the room together who hadn’t been able to find the time, or the song provides a vehicle for talking about a topic that would otherwise be repeatedly put on the shelf for another day. Listening for process in this way can encourage audience members who view the video, too, to use this communally crafted artistic labor as an invitation for connection.

“Revitalize” particularly serves as an example of how making a music video can involve collaboration with family and friends over an extended period, encompassing years of documentation and strengthening relationships. In addition to sharing a past and inspiring interaction for the making of the video, the song carries hopes for a future. As T-Rhyme says, “I want “Revitalize” to be a catalyst for healing and pride.” Paying attention to how musicians tell their stories and build relationships through music videos is part of recognizing their sovereignty and cultural continuity through sound and visuals.

—

Featured Image: Still from music video for “Revitalize” by T-Rhyme (2021)

—

Dr. Liz Przybylski (pronunciation) is an ethnomusicologist and pop music scholar working in hip hop and electronic music in the US and Canada. Dr. Przybylski is an Associate Professor of Ethnomusicology at the University of California, Riverside. A graduate of Bard College (BA) and Northwestern University (MA, PhD), Liz’s research appears in Ethnomusicology, Journal of Borderlands Studies, and IASPM Journal, among others. Dr. Przybylski has presented research nationally and internationally, including at the Society for Ethnomusicology, Native American and Indigenous Studies Association, Feminist Theory and Music, International Association for the Study of Popular Music, and International Council for Traditional Music World Conferences. Recent and forthcoming publications analyze how the sampling of heritage music in Indigenous hip hop contributes to dialogues about cultural change in urban areas. Dr. Przybylski has also published on popular music pedagogy. Liz was awarded a National Endowment for the Humanities Faculty Fellowship and a Fulbright Fellowship. Liz’s most recent book Sonic Sovereignty: Hip Hop, Indigeneity, and Shifting Popular Music Mainstreams was published in July 2023 (NYU Press). This follows Liz’s first book, Hybrid Ethnography: Online, Offline, and In Between (SAGE Publications, 2020) which develops an innovative model of hybrid on- and off-line ethnography for the analysis of expressive culture. In addition to university teaching, Liz has taught adult and pre-college learners at the American Indian Center in Chicago and the Concordia Language Villages program of Concordia College in Bemidji. On the radio, Liz hosted the world music show “Continental Drift” on WNUR in Chicago and has conducted interviews with musicians for programs including “At The Edge of Canada: Indigenous Research” on CJUM in Winnipeg. Dr. Przybylski served as the Media Reviews Editor for the journal American Music, the President of the Society for Ethnomusicology, Southern California and Hawaii Chapter, and on the Society for Ethnomusicology Council.

—

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Sounding Out! Podcast #40: Linguicide, Indigenous Community and the Search for Lost Sounds–Marcella Ernest

The “Tribal Drum” of Radio: Gathering Together the Archive of American Indian Radio–Josh Garrett Davis

Sonic Connections: Listening for Indigenous Landscapes in Kent Mackenzie’s The Exiles–Laura Sachiko Fugikawa

Unsettling the World Soundscape Project: Soundscapes of Canada and the Politics of Self-Recognition–Mitchell Akiyama

Becoming Sound: Tubitsinakukuru from Mt. Scott to Standing Rock–Dustin Tahmahkera

EPISODE 60: Standing Rock, Protest, Sound and Power–Marcella Ernest

A Tribe Called Red Remixes Sonic Stereotypes–Christina Giancona

I’m on my New York s**t”: Jean Grae’s Sonic Claims on the City––Liana Silva

How not to listen to Lemonade: music criticism and epistemic violence–Robin James

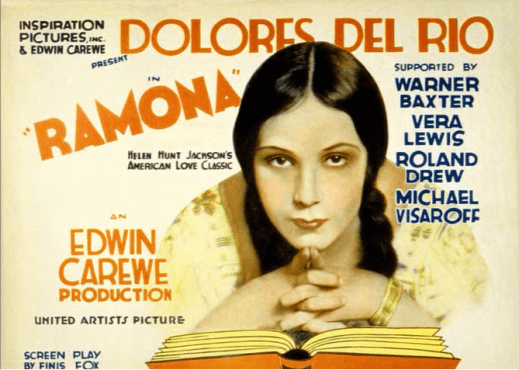

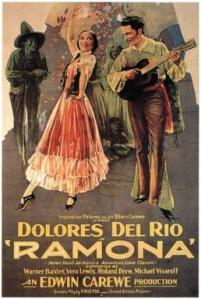

Playin’ Native and Other Iterations of Sonic Brownface in Hollywood Representations of Dolores Del Río

Mexican actress Dolores Del Río is admired for her ability to break ground; her dance skills allowed her to portray roles not offered to many women of color early in the 20th Century. One of her most popular roles was in the movie Ramona (1928), directed by Edwin Carewe. Her presence in the movie made me think about sonic representations of mestizaje and indigeneity through the characters portrayed by Del Río. According to Priscilla Ovalle, in Dance and the Hollywood Latina: Race, Sex and Stardom (2010), Dolores del Río was representative of Mexican nationhood while she was a rising star in Hollywood. Did her portrayals reinforce ways of hearing and viewing mestizos and First Nation people in the American imaginary? Is it sacrilegious to examine the Mexican starlet through sonic brownface? I explore these questions through two films, Ramona and Bird of Paradise (1932, directed by King Vidor), where Dolores del Río plays a mestiza and a Polynesian princess, respectively, to understand the deeper impact she had in Hollywood through expressions of sonic brownface.

Before I delve into analysis of these films and the importance of Ramona the novel and film adaptions, I wish to revisit the concept of sonic brownface I introduced here in SO! in 2013. Back then, I argued that the movie Nacho Libre and Jack Black’s characterization of “Nacho” is sonic brownface: an aural performativity of Mexicanness as imagined by non-Mexicans. Jennifer Stoever, in The Sonic Color Line (2017), postulates that how we listen to particular body(ies) are influenced by how we see them. The notion of sonic brownface facilitates a deeper examination of how ethnic and racialized bodies are not just seen but heard.

Through my class lectures this past year, I realized there is more happening in the case of Dolores del Río, in that sonic brownface can also be heard in the impersonation of ethnic roles she portrayed. In the case of Dolores del Río, though Mexicana, her whiteness helps Hollywood directors to continue portraying mestizos and native people in ways that they already hear them while asserting that her portrayal helps lend authenticity due to her nationality. In the two films I discuss here, Dolores del Río helps facilitate these sonic imaginings by non-Mexicans, in this case the directors and agent who encouraged her to take on such roles. Although a case can be made that she had no choice, I imagine that she was quite astute and savvy to promote her Spanish heritage, which she credits for her alabaster skin. This also opens up other discussions about colorism prevalent within Latin America.

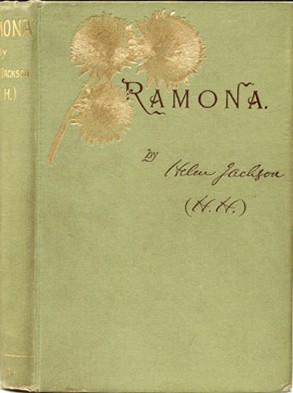

First, let us focus on the appeal of Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona (1884), as it is here that the cohabitation of Scots, Spanish, Mestizos, and Native people are first introduced to the American public in the late 19th century. According to Evelyn I. Banning, in 1973’s Helen Hunt Jackson, the author wanted to write a novel that brought attention to the plight of Native Americans. The novel highlights the new frontier of California shortly after the Mexican American War. Though the novel was critically acclaimed, many folks were more intrigued with “… the charm of the southern California setting and the romance between a half-breed girl raised by an aristocratic Spanish family and an Indian forced off his tribal lands by white encroachers.” A year after Ramona was published, Jackson died and a variety of Ramona inspired projects that further romanticized Southern California history and its “Spanish” past surged. For example, currently in Hemet, California there is the longest running outdoor “Ramona” play performed since 1923. Hollywood was not far behind as it produced two silent-era films, starring Mary Pickford and Dolores del Río.

First, let us focus on the appeal of Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona (1884), as it is here that the cohabitation of Scots, Spanish, Mestizos, and Native people are first introduced to the American public in the late 19th century. According to Evelyn I. Banning, in 1973’s Helen Hunt Jackson, the author wanted to write a novel that brought attention to the plight of Native Americans. The novel highlights the new frontier of California shortly after the Mexican American War. Though the novel was critically acclaimed, many folks were more intrigued with “… the charm of the southern California setting and the romance between a half-breed girl raised by an aristocratic Spanish family and an Indian forced off his tribal lands by white encroachers.” A year after Ramona was published, Jackson died and a variety of Ramona inspired projects that further romanticized Southern California history and its “Spanish” past surged. For example, currently in Hemet, California there is the longest running outdoor “Ramona” play performed since 1923. Hollywood was not far behind as it produced two silent-era films, starring Mary Pickford and Dolores del Río.

The charm of the novel Ramona is that it reinforces a familiar narrative of conquest with the possibility of all people co-existing together. As Philip Deloria reminds us in Playing Indian (1999), “The nineteenth-century quest for a self-identifying national literature … [spoke] the simultaneous languages of cultural fusion and violent appropriation” (5). The nation’s westward expansion and Jackson’s own life reflected the mobility and encounters settlers experienced in these territories. Though Helen Hunt Jackson had intended to bring more attention to the mistreatment of native people in the West, particularly the abuse of indigenous people by the California Missions, the fascination of the Spanish speaking people also predominated the American imaginary. To this day we still see in Southern California the preference of celebrating the regions Spanish past and subduing the native presence of the Chumash and Tongva. Underlying Jackson’s novel and other works like Maria Amparo Ruiz De Burton The Squatter and the Don (1885) is their critique of the U.S. and their involvement with the Mexican American War. An outcome of that war is that people of Mexican descent were classified as white due to the signing of Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and were treated as a class apart. (See Michael Olivas’ anthology, Colored Men and Hombres Aqui from 2006 and Ignacio M. García, White but not Equal from 2008). These novels and films reflect the larger dominant narrative of whiteness and its relationship to nation building. Through Pickford’s and del Río’s portrayals of Ramona they reinforce the whiteness of mestizaje.

Screenshot from RAMONA (1910). Here, Ramona (played by Mary Pickford) finds out that she has “Indian blood.”

In 1910, Mary Pickford starred in D.W. Griffith’s short film adaptation of Ramona as the titular orphan of Spanish heritage. Henry B. Walthall played Alessandro, the Native American, in brownface to mimic physical attributes of the native Chumash of Southern California. Griffith also wanted to add authenticity by filming in Camulas, Ventura County, the land of the Chumash and where Jackson based her novel. The short is a sixteen-minute film that takes viewers through the encounter between Alessandro and Ramona and their forbidden love, as she was to be wedded to Felipe, a Californio. There is a moment in the movie when Ramona is told she has “Indian blood”. Exalted, Mary Pickford says “I’m so happy” (6:44-6:58). Their short union celebrates love of self and indigeneity that reiterates Jackson’s compassionate plea of the plight of native people. In the end, Alessandro dies fighting for his homeland, and Ramona ends up with Felipe. Alessandro, Ramona, and Felipe represent the archetypes in the Westward expansion. None had truly the power but if mestizaje is to survive best it serve whiteness.

Edwin Carewe’s rendition of Ramona in 1928 was United Artists’ first film release with synchronized sound and score. Similar to the Jazz Singer in 1927, are pivotal in our understanding of sonic brownface. Through the use of synchronized scored music, Hollywood’s foray into sound allowed itself creative license to people of color and sonically match it to their imaginary of whiteness. As I mentioned in my 2013 post, the era of silent cinema allowed Mexicans in particular, to be “desirable and allowed audiences to fantasize about the man or woman on the screen because they could not hear them speak.” Ramona was also the first feature film for a 23-year-old Dolores del Río, whose beauty captivated audiences. There was much as stake for her and Carewe. Curiously, both are mestizos, and yet the Press Releases do not make mention of this, inadvertently reinforcing the whiteness of mestizaje: Del Río was lauded for her Spanish heritage (not for being Mexican), and Carewe’s Chickasaw ancestry was not highlighted. Nevertheless, the film was critically acclaimed with favorable reviews such as Mordaunt Hall’s piece in the New York Times published May 15, 1928. He writes, “This current offering is an extraordinarily beautiful production, intelligently directed and, with the exception of a few instances, splendidly acted.” The film had been lost and was found in Prague in 2005. The Library of Congress has restored it and is now celebrated as a historic film, which is celebrating its 90th anniversary on May 20th.

In Ramona, Dolores del Río shows her versatility as an actor, which garners her critical acclaim as the first Mexicana to play a starring role in Hollywood. Though Ramona is not considered a talkie, the synchronized sound comes through in the music. Carewe commissioned a song written by L. Wolfe Gillbert with music by Mabel Wayne, that was also produced as an album. The song itself was recorded as an instrumental ballad by two other musicians, topping the charts in 1928.

In the movie, Ramona sings to Allessandro. As you will read in the lyrics, it is odd that it is not her co-star Warner Baxter who sings, as the song calls out to Ramona. Del Río sounds angelic as the music creates high falsettos. The lyrics emphasize English vernacular with the use of “o’er” and “yonder” in the opening verse. There are moments in the song where it is audible that Del Río is not yet fluent speaking, let alone singing in English. This is due to the high notes, particularly in the third verse, which is repeated again after the instrumental interlude.

I dread the dawn

When I awake to find you gone

Ramona, I need you, my own

Each time she sings “Ramona” and other areas of the song where there is an “r”, she adds emphasis with a rolling “r,” as would be the case when speaking Spanish. Through the song it reinforces aspects of sonic brownface with the inaudible English words, and emphasis on the rolling “rrrr.” In some ways, the song attempts to highlight the mestiza aspects of the character. The new language of English spoken now in the region that was once a Spanish territory lends authenticity through Dolores del Río’s portrayal. Though Ramona is to be Scottish and Native, she was raised by a Spanish family named Moreno, which translates to brown or darker skin. Yes, you see the irony too.

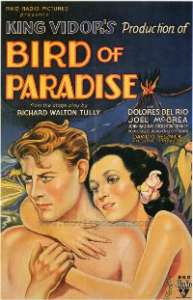

United Artists Studio Film Still, under Fair Use

Following Del Río’s career, she plays characters from different parts of the world, usually native or Latin American. As Dolores del Río gained more popularity in Hollywood she co-starred in several movies such as Bird of Paradise (1932), directed by King Vidor, in which she plays a Polynesian Princess. Bird of Paradise focuses on the love affair between the sailor, played by Joel McCrea, and herself. The movie was controversial as it was the first time we see a kiss between a white male protagonist with a non-Anglo female, and some more skin, which caught the eye of The Motion Picture Code commission. Though I believe the writers attempted to write in Samoan, or some other language of the Polynesian islands, I find that her speech may be another articulation of sonic brownface. Beginning with the “talkies,” Hollywood continued to reiterate stereotypical representations though inaccurate music or spoken languages.

In the first encounter between the protagonists, Johnny and Luana, she greets him as if inviting him to dance. He understands her. He is so taken by her beauty that he “rescues” her to live a life together on a remote island. Though they do not speak the same language at first it does not matter because their love is enough. This begins with the first kiss. When she points to her lips emphasizing kisses, which he gives her more of. The movie follows their journey to create a life together but cannot be fully realized as she knows the sacrifice she must pay to Pele.

I do not negate the ground breaking work that Dolores del Río accomplished while in Hollywood. It led her to be an even greater star when she returned to Mexico. However, even her star role as Maria Candelaria bares some examination through sonic brownface. It is vital to examine how the media reinforces the imaginary of native people as not well spoken or inarticulate, and call out the whiteness of mestizaje as it inadvertently eliminates the presence of indigeneity and leaves us listening to sonic brownface.

—

reina alejandra prado saldivar is an art historian, curator, and adjunct lecturer in the Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies Program and Liberal Studies Department at CSULA and in the Critical Studies Program at CALArts. As a cultural activist, she focused her earlier research on Chicano cultural production and the visual arts. Prado is also a poet and performance artist known for her interactive durational work Take a Piece of my Heart as the character Santa Perversa (www.santaperversa.com) and is currently working on her first solo performance entitled Whipped!

—

Featured image: Screenshot from “Ramona (1928) – Brunswick Hour Orchestra”

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Afecto Caribeño / Caribbean Affect in Desi Arnaz’s “Babalú Aye” – reina alejandra prado saldivar

SO! Amplifies: Shizu Saldamando’s OUROBOROS–Jennifer Stoever

SO! Reads: Dolores Inés Casillas’s ¡Sounds of Belonging! – Monica de la Torre

Recent Comments