Technologies of Communal Listening: Resonance at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

In both sound studies and the sonic arts, the concept of “resonance” has increasingly played a central role in attuning listeners to the politics of sound. The term itself is borrowed from acoustics, where resonance simply refers to the transfer of energy between two neighboring objects. For example, plucking a note on one guitar string will cause the other strings to vibrate at a similar frequency. When someone or something makes a sound, everything in the immediate environs—objects, people, the room itself—will respond with sympathetic vibrations. Simply put, in acoustics, resonance describes a sonic connection between sounding objects and their environment. In the arts, the concept of resonance emphasizes the situated existence of sound as a transformative encounter between bodies in a particular time and place. Resonance has become a key term to think through how sound creates a listening community, a transitory assemblage whose reverberations may be felt beyond a single moment of encounter.

For its recent performance series, simply called Resonance, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago drew on this generative concept by bringing together four artists who explore sound as an “introspective force for greater understanding, compassion, and change.” Curated by Tara Aisha Willis and Laura Paige Kyber, the series builds on theories of resonance as an affective relationship between sounding bodies developed by writers and artists like Sonia Louis Davis, Karen Christopher, and Birgit Abels. Crucially, the curators cite composer Juliana Hodkinson’s definition of resonance as an action occurring “when the space between subject and object starts to be reduced, without them fusing into one.” Sound has the capacity for creating a moment of connection, but resonance doesn’t efface difference. As Willis notes in the series program, the artists in the series largely identify as women of color, occupying a position “where distinction and difference are most ingrained in lived experience, and where practice of creating resonance across them are most honed.”

Although the artists in the series, Anita Martine Whitehead, Samita Sinha, Laura Ortman, and 7NMS, are at least partially working within musical traditions, the curators’ framing of the series in terms of sound rather than music speaks to a broader aural turn that has animated both sonic art and scholarship. The essential conceptual move underlying the growth of sound art in the museum and sound studies in the academy is the identification of sound as a medium of expression not fully contained by the history of music. Abstracting from the realm of music to the broader terrain of sound allows these artists to reconsider the materiality of sound and practices of listening—in short, to explore the resonant relations between bodies coexisting in time and space. Yet these pieces do not search for an ahistorical sonic ontology, but instead use sound as a situated tool to forge new social realities in the present. As the artist Samita Sinha puts it, her piece “offers technologies of listening and being together.” Thinking of listening in terms of resonance, we can hear these works as technologies of communal listening.

The series kicked off with the world premiere of Anna Martine Whitehead’s FORCE! an opera in three acts. I attended the evening of March 28, the first of three scheduled performances. Each performance in the series began at 7:30pm at the MCA’s Edlis Neeson Theater. The experimental musical work is an oneiric meditation on the US carceral state centered on the experience of trio of Black femmes passing time in a prison waiting room, ruminating on their dreams, living with state violence, and the unceasing passage of time. Choreographed and co-written by Whitehead, this particular performance of FORCE began with the audience congregated outside the museum’s Edlis Neeson Theater in the transitional space of the lobby, appropriately waiting for the show to start. The opera’s first act took in this space, as a group of performers entered and sat on the grand spiral stairs of the MCA, patiently biding their time. After a few minutes, a mass of four dancers joined them, slowly making their way down the long lobby corridor towards the group on the stairs; their bodies rhythmically moved as one, limbs interlinked and breathing heavy as if burdened by an invisible weight.

The choreography of FORCE continued this motif, as weary bodies became enmeshed, leaning and relying on each other for support. When this phalanx reached the stairwell and laboriously climbed as a unit, the first song began and their voices resonated through the halls of the museum. From there, the audience members were led to the stage not through the theater’s main doors, but through the innards of the museum. Laying the institution bare, the performers led us downstairs through hallways of lockers, then backstage, before we finally took our seats on stage.

The majority of FORCE is then performed on a bare theater stage, the audience in rows encircling the singers and dancers accompanied by a small ensemble of bass, drums, and keys. Just as the audience surrounds the stage, an array of speakers arranged along the edges of the room faces inward to create a shared soundscape inhabited by both the spectators and performers. As an opera, FORCE presents less a linear narrative than a series of songs swirling with reoccurring motifs that, through their repetition, suggest the temporality of waiting. One of the most powerful of these lyrical motifs introduced early in the show is that of fungal growth, of lichens felt on the body, in the nose, and on the eyes. This bivalent image of fungus both points towards an omnipresent carceral power felt on the body, while also recognizing the strategic possibilities of rhizomatic forms. The major theme of the work is of course waiting and time itself, with the singers repeatedly asking how long they have been here—the waiting room, the prison system, the police state—and how much longer they may have yet to go.

While addressing these weighty themes, the work still makes space for the possibility of joy and alternative futures. The performance ends with the singers repeating lines about freedom in a song that never concludes. As we exited, again through the bowels of the MCA, the song reverberated from the theater into the lobby. If FORCE’s first act took place before the audience entered the space of the theater, then the third act likewise continued beyond these four walls as our temporary listening community dispersed into the streets of Chicago. Even after the show, the song did not end.

The second work in the series, Samita Sinha’s Tremor built on these themes of power, space, and sonic connections between resonating bodies. I attended the first of three performances at the MCA on the evening of April 18. Performed on a minimal stage set designed by architect Sunil Bald consisting of three dramatic red sashes suspended from the ceiling, Tremor is an hour-long piece centered on Sinha’s “unraveling” of Indian vocal traditions. Of the artists in this performance series, Sinha perhaps most explicitly explored the theme of resonance, describing her work as “the practice of attuning oneself to the raw material of vibration and its emergence in space, as well as unfolding the possibilities that arise from encounters between this sonic material and other individuals.” In Tremor, the artist is accompanied by the dancer Darrell Jones, vocalist Sunder Ganglani, and an electronic soundscape created live by Ash Fure. As in FORCE, the audience was seated on the stage around the performers, with the shared sonic environment emphasizing the coexistence of our bodies in space.

In broad strokes, Tremor demonstrates the power of sonic community in the face of entropy, presenting a pair of singers competing with a barrage of electronic sound, finding solace in each other’s voice, and ultimately emerging together after an overwhelming onslaught of noise. Accompanied by a low rumble of barely audible sound, the piece begans with the four performers entering the stage and walking in an ever-widening circle, a starting point of social dispersal. Sinha, Ganglani, and Fuhre then took their places at opposing corners of the stage, on cushions placed under the suspended sashes. Jones moved around the center of the stage in ways alternately suggesting ecstasy and pain. The vocalists tentatively began singing wordless vocalizations that tended to resolve to a single note, sometimes accompanied by Sinha’s droning ektara.

As the performance continued, the lights dim and Fure’s electronic sound become increasingly loud and abrasive, a heavily delayed electronic whirring alternately suggesting buzzsaws or heavy machinery. When this noise reached a sustained roaring climax, the dancer and singers moved to the center of the stage, forming a circle with their bodies. Finally, the electronic sound subsides, and the vocalists, led by Sinha, begin singing again—this time with a more supple melody, no longer abrasive vocalizations centered on a single note. This circle of bodies—the performers and we, the audience—have outlasted the assault of noise, co-existing in space, transformed and fortified by this resonant encounter.`

White Mountain Apache sound artist and musician Laura Ortman’s performance marked the release of her latest album, Smoke Rings Shimmers Endless Blur and it provocatively reframes the spatiality of resonance in temporal terms. Ortman performed twice at the MCA, and I attended the first night on April 26. White Mountain Apache sound artist and musician Laura Ortman’s performance marked the release of her latest album, Smoke Rings Shimmers Endless Blur and it provocatively reframes the spatiality of resonance in temporal terms. Where the idea of resonance largely has spatial connotations of synchronic coexistence, Ortman challenges us to think of resonance in terms of time and history through her use of looping sound. Curator Laura Paige Kyber points to this aspect of the artist’s practice, drawing on the work of writers Joseph M. Pierce and Mark Rifkin to argue against the linear time of settler history in favor of “many distinct and self-determined notions of time.” As Kyber suggests, while past histories may resonate through her work, Ortman’s vital sound-making confronts us forcefully in the present.

For her hour-long set, Ortman employed a minimal—but powerful—toolkit for her practice of “sculpting sound”: a single electrified violin run through a pedal board, occasionally supplemented by her voice, a whistle, and a small bell. Throughout the show, the violin was heavily augmented by distortion, delay, and a looping pedal run through a Fender amplifier. Ortman used the loop to build repeating layers of shoegaze-like fuzz over which she improvised on her violin, her bowing veering ecstatically between melodic phrases and rhythmic noise. For most of the performance, she was alone in front of the bare black wall of the Edlis Neeson Theater, with heavy fog machine haze dramatically lit by spotlights and two lines of fluorescent lights on the floor receding into a vanishing point at the back of the stage. She was also accompanied by two short films for the first half: footage of dramatic New Mexico landscapes shot in collaboration with Daniel Hyde and Echota Killsnight, and a video directed by Razelle Benally of Ortman performing in Prospect Park near her home in Brooklyn.

Like Ortman’s music, Benally’s film plays with time, freely shifting between slow motion and double time footage of her performance. Likewise, Ortman’s use of the loop inherently emphasized temporality; with each decaying loop, the past continues to noisily repeat in the present—yet remains with us even as it becomes harder to discern. But amidst the resonance of the past, we are confronted with the artist meeting us in the here and now. We continue to hear the past resonating with is its own distinct temporality and it becomes the basis for Ortman’s vital artistic practice in the present. At the end of her performance, the loops fade away and we are ultimately faced with the artist standing before us sculpting sound with the violin.

The final work in the series, Prophet: The Order of the Lyricist by 7NMS, a collaboration between Marjani Forté-Saunders and Everett Saunders, centered on the figure of the Emcee and the tradition of hip-hop as powerful forces in the Black radical imagination. I attended the May 9 performance. Charting the creative journey of an aspiring lyricist, the piece mixes choreography by Forté-Saunders, an extended spoken-word monologue by Saunders, and a collage of music and sound partially drawn from the Sun Ra Collection at Chicago’s Experimental Sound Studio. Putting the communal ideals of resonance into practice, the artists developed this work in collaboration with the Chicago artistic community, finding inspiration from visits to the city’s South Side Community Arts Center, Stony Island Arts Bank, and Miyagi Records.

The performance begins with a choreographed prelude with Forté-Saunders and dancer Marcella Lewis moving together on a bare stage. Upon Saunders’s entrance onto the stage as the titular lyricist, Forté-Saunders and Lewis largely recede, becoming silent specters, moving through, and occasionally entering the ensuing narrative. In the first section, the lyricist recounted his youth training to be an emcee, adopting an increasingly martial cadence as he described his hard work developing breath control, free-styling, and rhyme-writing skills. This artistic intensity is followed by the most powerful part of the show: a long audio montage of interviews with other lyricists, their voices emanating from speakers surrounding Saunders. As their words ping-ponged from speaker to speaker, the narrator began flinging his body across the stage, before finally collapsing in a roar of white noise and projected static. From there, the lyricist described his further spiritual and political education under the tutelage of “three kings,” wise men he met on the streets of Philadelphia. In the show’s final moments, we watched the emcee frantically writing his lyrics on the stage floor, his words projected, resonating through the auditorium.

The diversity of performances in the series speaks to the capacious power of the concept of resonance, and the continued vitality of sound as a medium of expression. Through the series, sound was employed as a situated tool of connection, convening audience and performer in a communal space without eliding difference.

In her piece, Samita Sinha draws on the thinking of Caribbean philosopher’s Éduoard Glissant’s notion of trembling. Trembling thinking “is the instinctual feeling that we must refuse all categories of fixed and imperial thought … We need trembling thinking – because the world trembles, and our sensibility, our affect trembles … even when I am fighting for my identity, I consider my identity not as the only possible identity in the world.” Airek Beauchamp suggests a similar connection between sound and trembling, writing about the potential for sonic connection between marginalized queer bodies. Beauchamp argues that strategically deployed noise “communicates in trembles, resonating in both the psyche and the actual body,” coalescing disparate identities into a powerful social form. Trembling then, like resonance, doesn’t offer a single solution to global crises—likewise these artists do not treat sound as an inherently revelatory tool of political liberation. But through resonance, understood as a technology of communal listening, the artists invite us to hope for transformative encounters, for new ways of hearing the world.

—

Featured Image: Photo: Rachel Keane on https://mcachicago.org/

—

Harry Burson holds a PhD in Film & Media from the University of California, Berkeley. He researches and teaches on the theory and history of sonic media, exploring the intersection of digital and aural cultures, with particular focus on immersive media, sound art, and VR. His work examines how sound technologies have shaped both our understanding of and embodied relationship to digital media. He is currently a Lecturer at the University of Illinois Chicago (hburson@uic.edu)

—

This article also benefitted from the editorial review of Dahlia Bekong. Thank you!

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig this:

SO! Amplifies: Wu Tsang’s Anthem (2021)—Freddie Cruz Nowell

Freedom Back: Sounding Black Feminist History, Courtesy the Artists–Tavia Nyong’o

My Time in the Bush of Drones: or, 24 Hours at Basilica Hudson–Robert Ryan

The Sound of What Becomes Possible: Language Politics and Jesse Chun’s 술래 SULLAE (2020)—Casey Mecija

SO! Amplifies: Wu Tsang’s Anthem (2021)

SO! Amplifies. . .a highly-curated, rolling mini-post series by which we editors hip you to cultural makers and organizations doing work we really really dig. You’re welcome! We are excited that today’s post on Wu Tsang’s Anthem, currently on view at the Guggenheim through September 6, 2021, is written by Freddie Cruz Nowell, co-author of the exhibition texts! He is related to the curator of the exhibition and cares deeply about the collaborative, creative endeavors of Wu Tsang & Moved by the Motion.

—

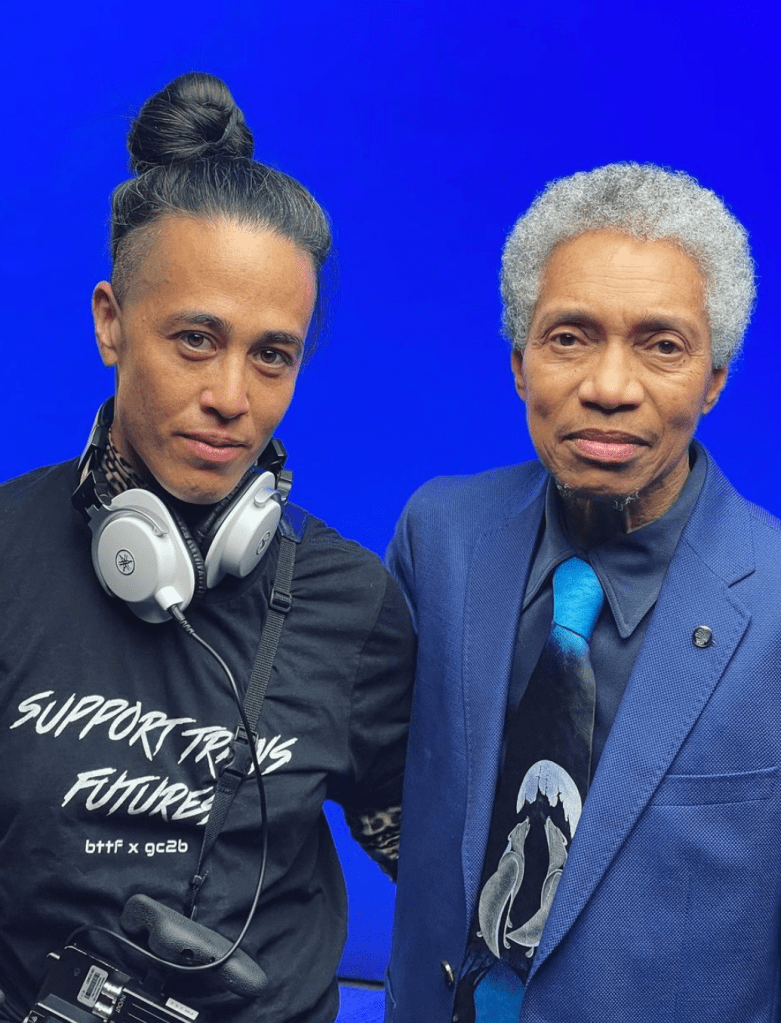

The artist and filmmaker Wu Tsang (b. 1982) creates atmospheric performances, video installations, and films that envelop audiences into spaces where narratives become sensually ambiguous, collective experiences. Tsang’s new site-specific installation, Anthem (2021), was conceived in collaboration with the singer, composer, and transgender activist Beverly Glenn-Copeland (b. 1944, Philadelphia) and harnesses the Guggenheim Museum’s cathedral-like acoustics to construct what the artist calls a “sonic sculptural space.”

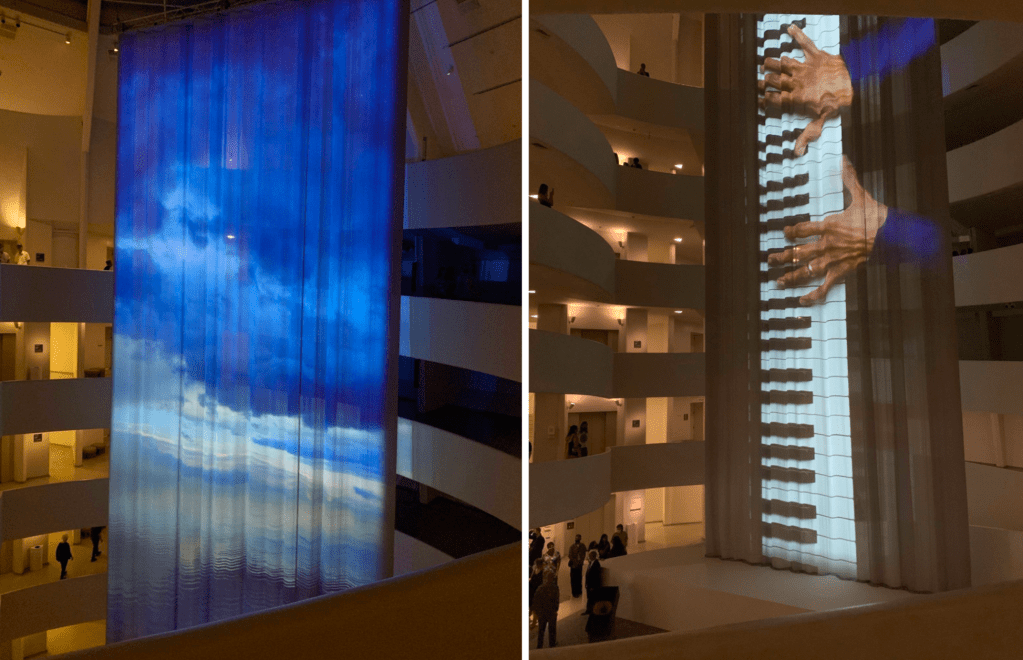

Occupying the entire rotunda, Anthem revolves around an immense, eighty-four-foot curtain sculpture that flows down from the building’s glass oculus. Projected onto this luminous textile is a “film-portrait” Tsang created of Glenn-Copeland improvising and singing passages of his music, including a cappella descants and his rendition of the spiritual “Deep River.” Filmed during the COVID-19 pandemic, near Glenn-Copeland’s home in rural Nova Scotia, this non-linear video alternates between scenes of the musician performing with various instruments and stunning landscape shots of the eastern seaboard sky.

Instrument and Landscape View of Wu Tsang’s Anthem (2021), Images courtesy of The Guggenheim

Harnessing the generous sound-reflecting quality of the Guggenheim’s concrete walls, Anthem weaves Glenn-Copeland’s voice and body percussion into a larger tapestry of other voices and sounds placed along the museum’s circular ramp, building a soundscape that wraps around the space. When I asked the exhibition’s curator X Zhu-Nowell about the striking ethereal, translucent quality of the curtain sculpture, X remarked,

It was a collaboration with the textile company Kvadrat. Wu visited their showroom a few times to select textile from thousands of the samples. This particular textile called power is semi translucent (created almost a hologram feeling), but still able to capture the light from the projectors very well. Wu once said that ‘when there is a curtain in the space, it turns the space into a stage.’ Curtain is very important to Wu’s practice.

The installation’s dimmed light ambiance also veils the fourteen speakers that Tsang positioned along this darkened path, each of which plays a uniquely composed track that accompanies Glenn-Copeland’s music.

Working in collaboration with musician Kelsey Lu and the DJ, producer, and composer duo of Asma Maroof and Daniel Pineda, Tsang conceived this arrangement of sounds as a series of improvisatory responses inspired by the call of Glenn-Copeland’s voice. The musical responses created by this diverse group of musicians include ethereal string tremolos, dreamy whisper sequences, and impromptu drum patterns, among other ambient sounds that help cultivate an alluring and reverberant listening environment.

Harnessing the generous sound-reflecting quality of the Guggenheim’s concrete walls, Anthem weaves Glenn-Copeland’s voice and body percussion into a larger tapestry of other voices and sounds placed along the museum’s circular ramp, building a soundscape that wraps around the space. X Zhu-Nowell described the process for the exhibit’s speaker placement:

We had a few mock-up to test the speaker placement. The two loudspeakers are placed on the rotunda floor because it’s unique capacity to fill the entire rotunda. The 12 additional Bose speakers were placed throughout ramp 3 – 6. We evenly distributed them, 3 speakers for each ramp. Ultimately, the goal is to work with the unique acoustics of the building, and working with the decay, allowing the time and space for the sound to bound on the concrete walls. The piece is 18 mins long, and in a continuous loop. It was not designed to cultivate a single prime viewing location. Instead, the piece was built to be experienced as one move through the space, and 18 mins is around the pace of one walk from the bottom of the rotunda floor to the top of ramp 6.

Visitors are encouraged to traverse upward from the bottom of the museum to the top of the building, and vice versa, and explore how Anthem ascends and descends along the spiral path.

Alternative View of Ramp: Wu Tsang’s Anthem (2021)

The title of this exhibition, Anthem, draws from lesser-known histories of the word meaning antiphon, a style of call-and-response singing associated with music as a spiritual practice. Unlike a conventional anthem, which amplifies the power of a song through loudness and uniform sound, this installation enhances the call of Glenn-Copeland’s voice by combining it with ambiguous vocal timbres, changing tints of ambient sound, and other heterogeneous sonic and visual textures. Within this lush yet complicated auditory environment, Tsang’s Anthem also cultivates moments of quiet, rest, and reflection, reimagining the rotunda as a compassionate atmosphere for collective listening and looking.

In addition to the immersive video installation on view in the rotunda, this exhibition also includes a touching companion film, titled “∞,” which visitors can access behind a luxe pleated curtain that divides the first floor side gallery from the main space. This video is a short interview that Tsang shot during the filming of Anthem of Glenn-Copeland and his partner, Elizabeth Glenn-Copeland, a theater artist, storyteller, and arts educator.

This dialogue captures autobiographical aspects of the couple’s intertwined creative process and artistic development, reflecting on myriad meanings of love in relation to their lives and work. Within the context of the oppressive and exploitive conditions of transgender “visibility” in contemporary culture, Tsang’s seemingly conventional yet uncommon record of this elderly and interracial couple exists in tension with the normative frame of transgender representation. It also extends the conversation within Tsang’s artistic practice around the centrality of collaboration, specifically long-term and intimate collaboration.

Photo of Wu and Glenn on set in Nova Scotia, from Wu Tsang’s IG feed

Since 2016, Tsang has frequently worked with a “roving band” of interdisciplinary artists called Moved by the Motion, cofounded with the artist Tosh Basco. Core members of this revolving cast include Maroof, Pineda, the dancer Josh Johnson, the cellist Patrick Belaga, and the poet and scholar Fred Moten. Anthem exemplifies how she uses collaboration as an aesthetic strategy for undoing conventional modes of authorship and to make space for marginalized narratives. For Tsang, “making art is an excuse to collaborate.”

On View at the Guggenheim, New York City, July 23-September 6, 2021

—

Featured Image: Still of banner/ installation View of Wu Tsang’s Anthem (2021) at the Guggenheim, courtesy of curator X Zhu-Nowell

—

Frederick Cruz Nowell is a Ph.D. Candidate in Musicology at Cornell University. He is a scholar with a specialty in historical avant-gardes, and cross-disciplinary research into the history of music theory, contemporary art, and popular music. His dissertation research (Supervisor, Prof. Andrew Hicks) lies at the occult intersection of artistic experimentalism, Euro-American counterculture, and the history of music theory in the early twentieth century. It traces how speculative music-theoretical concepts (i.e., cosmic harmony, biological rhythms, color-harmony, and ontologies of sympathetic vibration) fused into the practices of European avant-garde artists via fashionable occult religious movements (i.e., Theosophy and Anthroposophy) and various cults of health and beauty (i.e., harmonic gymnastics, Eurythmics, free body culture (Freikörperkultur)). Intimately intertwined with one another, these social developments were integral to the larger infrastructure of the unwieldy “back to nature” Lebensreform (the reform of life) movement, which laid the foundations for progressive counterculture in the twentieth century.

Before pursuing graduate studies in musicology, Frederick was a University Fellow at Northwestern University in the Department of Art, Theory, & Practice, where he received an MFA. He also holds a BFA from SAIC (the School of the Art Institute of Chicago). Since 2018, he has co-curated exhibitions with X Zhu-Nowell under the moniker Passing Fancy.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig this:

Instrumental: Power, Voice, and Labor at the Airport--Asa Mendelsohn

SO! Amplifies: Anne Le Troter’s “Bulleted List”

“Finding My Voice While Listening to John Cage“–Art Blake

SO! Amplifies: Shizu Saldamando’s OUROBOROS

SO! Amplifies: Mendi+Keith Obadike and Sounding Race in America

Sound and Curation; or, Cruisin’ through the galleries, posing as an audiophiliac–reina alejandra prado

Recent Comments