SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests (Penn State University Press) is a book “about the sounds made by those seeking change” (5). It situates these sounds within a broader inquiry into rhetoric as sonic event and sonic action—forms of practice that are collective, embodied, and necessarily relational. It also addresses a long-standing question shared by many of us in rhetorical studies: Where did the sound go? And specifically, in a field that had centered at least half of its disciplinary identity around the oral/aural phenomena of speech, why did the study of sound and rhetoric require the rise of sound studies as a distinct field before it could regain traction?

Eckstein confronts this silence with urgency and clarity, offering a compelling case for how sound operates not just as a sensory experience but as a rhetorical force in public life. By analyzing protest environments where sound is both a tactic and a terrain of struggle, Sound Tactics reinvigorates our understanding of rhetoric’s embodied, affective, and spatial dimensions. What’s more, it serves as an important reminder that sound has always played an important role in studies of speech communication.

Rhetoric emerged in the Western tradition as the study and practice of persuasive speech. From Aristotle through his Greek predecessors and Roman successors, theorists recognized that democratic life required not just the ability to speak, but the ability to persuade. They developed taxonomies of effective strategies—structures, tropes, stylistic devices, and techniques—that citizens were expected to master if they hoped to argue convincingly in court, deliberate in the assembly, or perform in ceremonial life.

We’ve inherited this rhetorical tradition, though, as Eckstein notes early in Sound Tactics, in the academy it eventually splintered into two fields: one that continued to study rhetoric as speech, and another that focused on rhetoric as a writing practice. But somewhere along the way, even rhetoricians with a primary interest in speech moved toward textual representation of speech, rather than the embodied, oral/aural, sonic event that make up speech acts (see pgs 49-50).

Sound Tactics corrects this oversight first by broadening what counts as a “speech act”—not only individual enunciations, but also collective, coordinated noise. Eckstein then offers updated terminology and analytical tools for studying a wide range of sonic rhetorics. The book presents three chapter-length case studies that demonstrate these tools in action.

The first examines the digital soundbite or “cut-out” from X González’s protest speech following the school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. The second focuses on the rhythmic, call-and-response “heckling” by HU Resist during their occupation of a Howard University building in protest of a financial aid scandal. The third analyzes the noisy “Casseroles” retaliatory protests in Québec, where demonstrators banged pots and pans in response to Bill 78’s attempts to curtail public protest.

A full recounting of the book’s case studies isn’t possible here, but they are worth highlighting—not only for the issues Eckstein brings to light, but for how clearly they showcase his analytical tools and methods in action. These methods, in my estimation, are the book’s most significant contribution to rhetorical studies and to scholars more broadly interested in sound analysis.

Eckstein’s analytical focus is on what he calls the “sound tactic,” which is “the sound (adjective) use of sound (noun) in the act of demanding” (2). Soundness in this double sense is both effective and affective at the sensory level. It is rhetoric that both does and is sound work—and soundness can only be so within a particular social context. For Eckstein, soundness is “a holistic assessment of whether an argument is good or good for something” (14). Sound tactics, then, utilize a carefully curated set of rhetorical tools to accomplish specific argumentative ends within a particular social collective or audience capable of phronesis or sound practical judgement (16). Unsound tactics occur when sound ceases to resonate due to social disconnection and breakage within a sonic pathway (see Eckstein’s conclusion, where he analyzes Canadian COVID-19 protests that began with long-haul truck drivers, but lost soundness once it was detached from its original context and co-opted by the far right).

Just as rhetorical studies has benefitted from the influence of sound studies, Eckstein brings rhetorical methods to sound studies. He argues that rhetoric offers a grounding corrective to what he calls “the universalization of technical reason” or “the tendency to focus on the what for so long that we forget to attend to the why” (29). Following Robin James’s The Sonic Episteme: Acoustic Resonance, Neoliberalism, and Biopolitics, he argues that sound studies work can objectify and thus reify sound qua sound, whereas rhetoric’s speaker/audience orientation instead foregrounds sound as crafted composition—shaped by circumstance, structured by power, and animated by human agency. Eckstein finds in sound studies the terminology for such work, drawing together terms such as acousmatics, waveform, immediacy, immersion, and intensity to aid his rhetorical approach. Each name an aspect of the sonic ecology.

Rhetoricians often speak of the “rhetorical situation” or the circumstances that create the opportunity or exigence for rhetorical action and help to define the relationship between rhetor and audience. While the rhetorical action itself is typically concrete and recognizable, the situation itself—which is always in motion—is more difficult to pin down. “Acousmatics” names a similar phenomenon within a sonic landscape. Noise becomes signal as auditors recognize and respond to particular kinds of sound—a process that requires cultural knowledge, attention, and the proverbial ear to hear. A sound’s origins within that situation may be difficult to parse. Acousmastics accounts for sound’s situatedness (or situation-ness) within a diffuse media landscape where listeners discern signal-through-noise, and bring it together causally as a sound body, giving it shape, direction, and purchase. As such a “sound body” has a presence and power that a single auditor may not possess.

Eckstein defines “sound body” as “our imaginative response to auditory cues, painting vivid, often meaningful narratives when the source remains unseen or unknown” (10). And while the sound body is “unbounded,” it “conveys the immediacy, proximity, and urgency typically associated with a physical presence (12). Thus, a sound body (unlike the human bodies it contains) is unseen, but nonetheless contained within rhetorical situations, constitutive of the ways that power, agency, and constraint are distributed within a given rhetorical context. Eckstein’s sound body is thus distinct from recent work exploring the “vocal body” by Dolores Inés Casillas, Sebastian Ferrada, and Sara Hinojos in “The ‘Accent’ on Modern Family: Listening to Vocal Representations of the Latina Body” (2018, 63), though it might be nuanced and extended through engagement with the latter. A focus on the vocal body brings renewed attention to the materialities of the voice—“a person’s speech, such as perceived accent(s), intonation, speaking volume, and word choice” and thus to sonic elements of race, gender, and sexuality. These elements might have been more explicitly addressed and explored in Eckstein’s case studies.

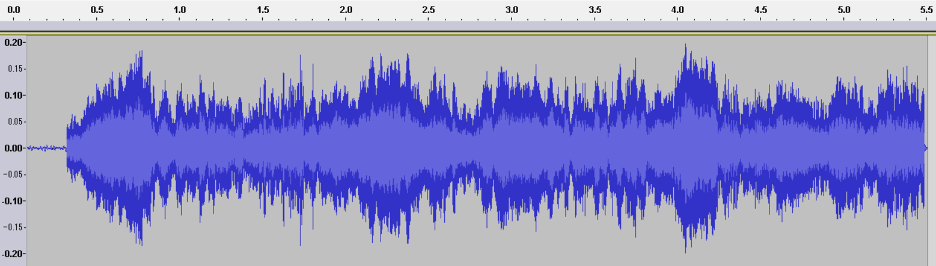

Eckstein uses these terms to help us understand the rhetorical complexities of social movements in our contemporary, digital world—movements that extend beyond the traditional public square into the diverse forms of activism made possible by the digital’s multiplicities. In that framework he offers the “waveform” as a guiding theoretical concept, useful for discerning the sound tactics of social movements. A waveform—the digital, visual representation of a sonic artifact—provides a model for understanding how sound takes shape, circulates, and exerts force. Waveforms also obscure a sound’s originating source and thus act acousmastically.

“[A] waveform is a visual representation of sound that measures vibration along three coordinates: amplitude, frequency, and time” (50). Eckstein draws on the waveform’s “crystallization” of a sonic moment as a metaphor to show sound’s transportability, reproducibility, and flexibility as a media object, and then develops a set of analytical tools for rhetorical analysis that match these coordinates: immediacy, immersion, and intensity. As he describes:

Immediacy involves the relationship between the time of a vibration’s start and end. In any perception of sound, there can be many different sounds starting and stopping, giving the potential for many other points of identification. Immersion encompasses vibration’s capacity to reverberate in space and impart a temporal signature that helps locate someone in an area; think of the difference between an echo in a canyon and the roar of a crowd when you’re in a stadium. Finally, intensity describes the pressure put on a listener to act. Intensity provides the feelings that underwrite the force to compel another to act. Each of these features and the corresponding impact of this experience offer rhetorical intervention potential for social movements. (51)

This toolset is, in my estimation, the book’s most cogent contribution for those working with or interested in sonic rhetorics. Eckstein’s case studies—which elucidate moments of resistance to both broad and incidental social problems—offer clear examples of how these interrelated aspects of the waveform might be brought to bear in the analysis of sound when utilized in both individual and collective acts of social resistance.

To highlight just one example from Eckstein’s three detailed case studies, consider the rhetorical use of immediacy in the chapter titled “The Cut-Out and the Parkland Kid.” The analysis centers on a speech delivered by X González, a survivor of the February 14, 2018, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida. Speaking at a gun control rally in Ft. Lauderdale six weeks after the tragedy, González employed the “cut-out,” a sound tactic that punctuated their testimony with silence.

Embed from Getty Images.

As the final speaker, González reflected on the students lost that day—students who would no longer know the day-to-day pleasures of friendship, education, and the promise of adulthood. The “cut-out” came directly after these remembrances: an extended silence that unsettled the expectations of a live audience disrupting the immediacy of such an event. As the crowd sat waiting, González remained resolute until finally breaking the silence: “Since the time that I came out here, it has been six minutes and twenty seconds […] The shooter has ceased shooting and will soon abandon his rifle, blend in with the students as they escape, and walk free for an hour before arrest” (69–70).

As Eckstein explains, González “needed a way to express how terrifying it was to hide while not knowing what was happening to their friends during a school shooting” (61). By timing the silence to match the duration of the shooting, the focus shifted from the speech itself to an embodied sense of time—an imaginary waveform of sorts that placed the audience inside the terror through what Eckstein calls “durational immediacy.” In this way, silence operated as a medium of memory, binding audience and victims together through shared exposure to the horrors wrought over a short period of time.

…

Sound Tactics is a must-read for those interested in a better understanding of sound’s rhetorical power—and especially how sonic means aid social movements. In conclusion, I would mention one minor limitation of Eckstein’s approach. As much as I appreciated his acknowledgement of sound’s absence from the Communication side of rhetoric, such a proclamation might have benefited from a more careful accounting of sound-related works in rhetorical studies writ large over the last few decades. Without that fuller context, readers may conclude that rhetorical studies has—with a few exceptions—not been engaged with sound. To be fair, the space and focus of Sound Tactics likely did not permit an extended literature review. There is thus an opportunity here to connect Eckstein’s important intervention with the work of other rhetoricians who have also been advancing sound studies.

I am including here a link to a robust (if incomplete) bibliography of sound-related scholarship that I and several colleagues have been compiling, one that reaches across Communication and Writing disciplines and beyond.

—

Featured Image: Family at the CLASSE (Coalition large de l’ASSÉ ) Demonstration in Montreal, Day 111 in 2012 by Flicker User scottmontreal CC BY-NC 2.0

—

Jonathan W. Stone is Associate Professor of Writing and Rhetoric at the University of Utah, where he also serves as Director of First-Year Writing. Stone studies writing and rhetoric as emergent from—and constitutive of—the mythologies that accompany notions of technological advance, with particular attention to sensory experience. His current research examines how the persisting mythos of the American Southwest shapes contemporary and historical efforts related to environmental protection, Indigenous sovereignty, and racial justice, with a focus on how these dynamics are felt, heard, and lived. This work informs a book project in progress, tentatively titled A Sense of Home.

Stone has long been engaged in research that theorizes the rhetorical affordances of sound. He has published on recorded sound’s influence in historical, cultural, and vernacular contexts, including folksongs, popular music, religious podcasts, and radio programs. His open-source, NEH-supported book, Listening to the Lomax Archive, was published in 2021 by the University of Michigan Press and investigates the sonic archive John and Alan Lomax created for the Library of Congress during the Great Depression. Stone is also co-editor, with Steph Ceraso, of the forthcoming collection Sensory Rhetorics: Sensation, Persuasion, and the Politics of Feeling (Penn State U Press), to be published in January 2026.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings –Vanessa Valdés

Quebec’s #casseroles: on participation, percussion and protest–-Jonathan Sterne

SO! Reads: Steph Ceraso’s Sounding Composition: Multimodal Pedagogies for Embodied Listening-–Airek Beauchamp

Faithful Listening: Notes Toward a Latinx Listening Methodology––Wanda Alarcón, Dolores Inés Casillas, Esther Díaz Martín, Sara Veronica Hinojos, and Cloe Gentile Reyes

The Sounds of Equality: Reciting Resilience, Singing Revolutions–Mukesh Kulriya

SO! Reads: Todd Craig’s “K for the Way”: DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies—DeVaughn Harris

Wingsong: Restricting Sound Access to Spotted Owl Recordings

I am not a board games person, yet I always seem to find myself surrounded by them. Such was the case one August evening in 2023, during a round of the bird-watching-inspired game, Wingspan. Released in 2019 by Stonemaier Games, designer Elizabeth Hargrave’s creation is credited with a dramatic shift in the board game industry. The game received an unparalleled number of awards, including the prestigious 2019 Kennerspiel des Jahres (Connoisseur Game of the Year), and an unheard of seven categories of the Golden Geek Awards, including Best Board Game of the Year and Best Family Board Game of the Year. In addition to causing shifts in typical board game topic, artistry, and demographic, Wingspan has led many board game fans to engage with the natural world in new ways, even inspiring many to become avid birders.

Following the game’s rise to popularity, developer Marcus Nerger released an app, Wingsong which allows players to scan each of the beautifully illustrated cards and play a recording of the associated bird’s song. On the evening in question, the unexpected occurred when I scanned the Spotted Owl (Strix occidentalis) card and received a message that read:

Playback of this birds[sic] song is restricted.

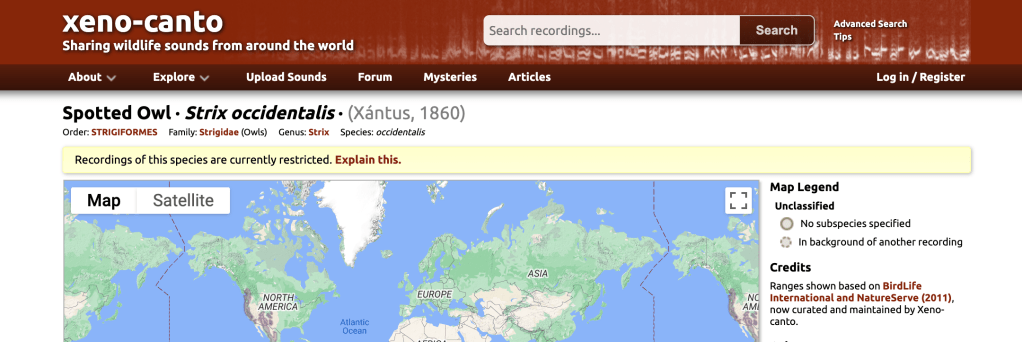

Of course, I had to know more. Although the board game was originally designed using information from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s eBird.org website, Wingsong derives its recordings from another free database, xeno-canto.org. A quick search of the website revealed the following statement:

Some species are under extreme pressure due to trapping or harassment. The open availability of high-quality recordings of these species can make the problems even worse. For this reason, streaming and downloading of these recordings is disabled. Recordists are still free to share them on xeno-canto, but they will have to approve access to these recordings.

Though Xeno-Canto does not give specific details about each recording, the Wingspan card offers a clue in italics at the bottom: “Habitat for these birds was a topic in logging fights in the Pacific Northwest region of the US.”

The unexpected incursion of such politics into a board game is startling, especially given the limited information in the initial message. As such, the restriction of Spotted Owl recordings on Xeno Canto, and by extension Wingsong, suggests complicated issues relating to the ownership and distribution of sound, censorship, and conservation.

Spotted Owl Recordings

The status of the Spotted Owl was a major issue of public debate in Oregon of the 1980s and 90s, where I grew up. As Dr. Rocky Gutiérrez, the “godfather” of Spotted Owl research, wrote in an article for The Journal of Raptor Research, “Conservation conflicts are always between people – not between people and animals” (2020, 338). In this case, concerns about the impacts of logging in old-growth forests, thought to be the primary habitat of the Spotted Owl, pitted loggers and the timber industry against conservationists. On both sides, national entities like the Sierra Club and the Western Timber Association helped turn a regional management issue into one with implications for forest protection, wildlife conservation, and economic development across the nation. Forty years later, it is still a hot button issue for scientists, industry, and the government, now with added complications of fire control, climate change, and competing species like the Barred Owl (Strix varia).

Xeno-Canto uses a Creative Commons license, meaning that users can access and apply to a wide variety of projects without explicit permission of the recordist, but it also offers tools for contacting other users. I wrote to two recordists who uploaded Spotted Owl calls to Xeno Canto: Lance Benner and Richard Webster, both recording in southern areas where the Spotted Owl’s conservation status is slightly less dire than in Oregon. Benner is a scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology, whose recordings have been used in scientific research projects, at nature centers, in phone apps, and notably, in a Canadian TV show. Benner told me via email that he agrees with Xeno-Canto’s restriction on the Spotted Owl recordings to the public, writing

I used to play spotted owl recordings when leading owl trips but I don’t any more now that the birds have been classified as “sensitive.” There have also been multiple attempts to add the California Spotted Owls to the endangered species list, so if I find them, I’m not sharing the information the way I used to….

Webster, on the other hand, offered a slightly different perspective:

There are enough recordings in the public domain that restricting XC’s recordings probably will not make a difference. However, some populations of Spotted Owl are threatened, and abuse is quite possible…

As Webster points out, numerous recordings of Spotted Owls are readily available, including via The Cornell Lab of Ornitology’s Voices of North American Owls and other audio field guides. The concern with such recordings, Gutiérrez told me over Zoom, is that anti-Spotted Owl activists might use the recordings to “call in” Spotted Owls – essentially a form of audio catfishing historically used in activities like duck hunting. In the case of Spotted Owls, the concern is that activists might deliberately harm the birds. However, it can also be a dangerous practice when used by birders who simply want to get a closer look: birds may abandon their nests, leaving chicks vulnerable and unprotected.

From a sound studies perspective, “calling in” underscores questions of avian personhood. Rachel Mundy contends that audio field guides are structured by people in ways that highlight animal musicianship. Yet when we consider the practice of “calling in,” it becomes clear that birdsong recordings are not only designed for human ears, but also avian ones.

Nonetheless, while birds are considered intelligent enough to recognize a call from their own species, they are not believed to be able to identify the difference between a recording and a live performance. The bird’s sensorium is short-circuited by the audio recording, tricking it into thinking a mate is nearby. Not only does this recall the interspecies history of the RCA Victor label His Master’s Voice, it highlights distinctly human anxieties about the role of recording and its ability to dissimulate. Restricting access to such recordings, then, revives deep-seated ethical questions that require a nuanced application.

Whether or not Spotted Owls are able to differentiate between a recorded call or the call of a live mate it is likely to be of decreasing concern, however: Gutiérrez suggests that Northern Spotted Owl populations are so small that anyone attempting to call one in would be unlikely to actually find one.

Immersion, Conservation, Reflection

App developer Marcus Nerger conceptualizes Wingsong as part of an immersive augmented reality experience, one that situates the game player in a more realistic soundworld. In the world of board games, parallels might be drawn to audio playlists used in tabletop role playing games like Dungeons and Dragons, or to the immersive soundscape design used in video games.

Via Zoom, Nerger and I discussed the importance of sound in bird identification, which is arguably more significant than vision given birds’ general fearfulness of humans, branch cover, and the physical distance bird and observer – a separation underscored by the pervasive use of technologies like binoculars. Wingsong is not simply immersive because it connects the player to the real bird species, but because the experience of birding relies as much on hearing as it does on sight.

However, the Spotted Owl restriction message provides a provocative interruption to the immersive bird song experience provided by Wingsong. It is a jarring contrast to the benign experience of listening to recorded bird song, reminding the player of both the artifice of game play and the consequences of environmental actions. It suggests that the birds in the game are not hyper realistic Pokémon to be simply collected, but rather living animals embedded in environmental and political histories. The lack of information provided in the “restricted” message leaves the player wanting more – and subsequently, with a bit of searching, unearthing the mechanics behind the app, the politics of bird song recording, and finally, the specific histories of the species contained there, the ghost in the machine irrevocably unveiled.

—

Featured Image: by author

—

Julianne Graper (she/her) is an Assistant Professor in Ethnomusicology at Indiana University Bloomington. Her work focuses on human-animal relationality through sound in Austin, TX and elsewhere. Graper’s writing can be found in Sound Studies; MUSICultures; forthcoming in The European Journal of American Studies and in the edited collections Sounds, Ecologies, Musics (2023); Behind the Mask: Vernacular Culture in the Time of COVID (2023); and Songs of Social Protest (2018). Her translation of Alejandro Vera’s The Sweet Penance of Music (2020) received the Robert M. Stevenson award from the American Musicological Society.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Animal Renderings: The Library of Natural Sounds — Jonathan Skinner

Sounding Out! Podcast #34: Sonia Li’s “Whale” — Sonia Li

Catastrophic Listening—China Blue

Learning to Listen Beyond Our Ears: Reflecting Upon World Listening Day–Owen Marshall

Botanical Rhythms: A Field Guide to Plant Music–Carlo Petrão

The Better to Hear You With, My Dear: Size and the Acoustic World--Seth Horovitz

The Screech Within Speech–-Dominic Pettman

Recent Comments