Heads: Reblurring The Lines

I don’t intend to discuss the “Blurred Lines” case in this post. There are plenty of folk already committing thoughts on the ruling. While the circumstances of the recent Thicke/Williams/Gaye case are not explicitly about sampling, they are indicative of the direction sample/copyright litigation can go in the future. When samples from a composition infringe upon the copyrights for the song, it is dangerous territory. Rather than focus on those dangers however, I’d like to exemplify possibilities of a more open (and arguably the intended) interpretation of copyright laws, by doing something I should have done seven years ago – put out my project Heads (dropping on April 1st, 2015).

My position has not changed from previous writings on sample laws – transformative sampling produces original work. My intent here is to present an artist’s statement on Heads that illustrates how transformative sampling and derivatives of it require broader interpretation; they should be legally covered as original compositions.

Cover art for Proto-Heads project from 2009

I’ve kept Heads in the vaults since 2007 while continuing from its artistic direction, all the while doing little tinkerings to convince myself it wasn’t done yet (it was). I had been pursuing analog technologies I swore would be the finishing touches it needed, to convince myself it wasn’t ready yet (it was). Then I lost 4TB of files in a quadruple hard drive killer power surge. The last Heads masters were among the 500GB that survived.

The project was born in response to comments made by Wynton Marsalis, dismissing hip-hop and denying its connection to the legacy of black music.

It’s mostly sung in triplets. So what? And as for sampling, it just shows you that the drummer has been replaced by a loop. The drum – the central instrument in African-American music, the sound of freedom – has been replaced by a repetitive loop. What does that tell you about hip-hop’s respect for African-American tradition? – Wynton Marsalis

I was offended as both a hip-hop and jazz head, so I set out to produce a body of work that showed the artistic originality of sampling and tied the practice to black musical traditions.

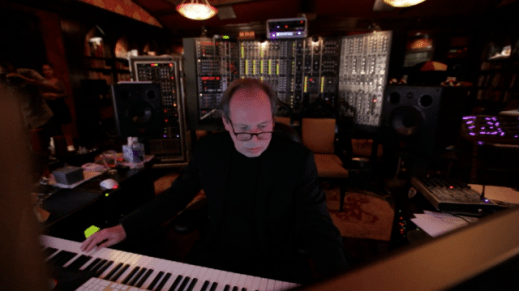

Prior to the analog experiments, I was modeling a series of digital Open Sound Control (OSC) instruments based on the monome, starting with a sampler but expanding into drum machines synthesizers and other noise makers. Together I called them the Heads Instruments. 95% of the composition work on Heads began with these instruments, all of which were built around the concept of sampling.

The title Heads, comes from the musical head, which is a fundamental part of the jazz tradition. The head is the thematic phrase or group of phrasings that signify a song; heads can be comprised of melody, harmony and/or rhythm. Jazz musicians use the head as a foundation for improvisation, a traditional form including the alternating of head and solo improvisations . Often times in jazz, the head comes from popular songs re-envisioned through improvisation in a jazz context, such as John Coltrane’s famous refiguring of “My Favorite Things” from The Sound of Music. In addition to being covers, these versions are transformations of the original into a different musical context. The Heads Instruments were designed specifically as instruments that could perform a head in a transformative manner.

Hip-hop attacks itself. It has no merit, rhythmically, musically, lyrically. What is there to discuss? – Wynton Marsalis

Tony Wynn

I was a bit annoyed at Marsalis, just how much is illustrated by the opening track of Heads, “Tony Wynn,” eponymously named after the contemporary jazz saxophonist, who, like Marsalis, feels that hip hop is not music. In it a character berates his friend for bringing up Wynn’s position. On the surface the song talks trash, but musically it makes layers of references.

First, the song’s format (down to the title) is a nod to the Prince tune “Bob George.” In his song, Prince parodies a character berating a girlfriend for being with Bob George. The voice of the character in “Tony Wynn” and some of his comments come straight from Prince’s song, but the work as a whole is not a direct cover of “Bob George.”

“Tony Wynn” is undeniably influenced by the Minneapolis sound, that eclectic late 1970s and early 80s scene that blend of funk, rock, and synthpop, but how the track arrives there is complicated. It does contain a Prince sample, but not from “Bob George.” The sample is played in a transformative manner, chopping a new riff different from the source material. It also includes a hit from another song, a sample of only one note, yet one identifiable as signature. The drums are ‘played’ in what could be described as the Minneapolis vibe. You can also hear a refrain that mimics yet another song. All of these sampled parts create a new head, to which I added instrumental embellishments with co-conspirator Dolphin on bass, synth, and the killer Prince-esque guitar solo.

The track represents a hodgepodge of Prince influences, but because those influences are so varied, none can be individually identified as the heart of “Tony Wynn.” Furthermore, at the bridge all of the samples get flipped on each other, some re-sampled and performed anew. Nothing can be pinned down as an infringement on technicalities, without taking into account the full context of the transformation. While “Tony Wynn” is heavily influenced by Prince, it is not a Prince song.

Rap Rap Rap

The second track on Heads,”Rap Rap Rap,” features Murda Miles and Killa Trane. I chose its title and head to reference the 1936 Louis Palma song “Sing Sing Sing,” made popular by the Benny Goodman Band. Coming out of the big band era, the song is closer to a traditionally composed Western standard, the heavy percussions however distinguish it. While you will find no samples of sound recordings from any version of “Sing Sing Sing” in “Rap Rap Rap,” it still represents the primary sample head used.

The opening percussive phrases are influenced by rhythmic hand games—an important but often overlooked precursor to hip hop discussed in Kyra Gaunt’s The Games Black Girls Play: Learning the Ropes from Double-Dutch to Hip-Hop. Here the rhythm sets the pace before charging into the head with a swing type of groove as the two featured artists, Murda Miles on trumpet and Killa Trane on sax, call out the head. What distinguishes these horns however, is that they are both sample based.

The song’s head is still based on “Sing Sing Sing,” but for the dueling horn parts the samples come from the recordings of Miles Davis and John. While Davis and Coltrane played together at a fair number of sessions, these samples come from two divergent sources from their individual catalogs. I chopped, tuned and arranged them for performance so that they could play in tune with the head.

The opening half of “Rap Rap Rap” sees both sticking to the head with little flourishes, but at the half way mark, the accompaniment changes to a distinct hip-hop beat still firmly rooted in the head. The two horns shift here as well, trading bars in a way that nods to both jazz and rap. The phrasing of the sample performance itself mimics a rapping cadence here, bridging the gap between the two traditions.

La Botella

The head for next track “La Botella” (The Bottle), uses a popular salsa motif as the head, accentuated by a son influenced percussive wall of sound. The percussions vary from live tracked percussions to percussion samples to percussive synthesis. I performed many of the percussive sounds utilizing the Heads Instruments sequencer, which lends itself to the slightly off—while still in the pocket—swing.

The format of this particular head allowed for an expanded arrangement, through which I nod to the Afro-Cuban influence in the African American tradition, from jazz to hard soul/funk to rock and roll. Son evolved from drumming traditions that have their own forms of the head. There is a duality in these two traditions that pairs a desire for tightness with a looseness in spirit, and this tension continues into musics influenced by them. The percussions on “La Botella” carry that duality. The collective drums sound as an instrument, while each individual drum can be aurally isolated.

The actual samples in the song come from vocal bits of The Fania All-Stars, but the true Fania mark I emulate on “La Botella” is the horn section. They sound nowhere near as good—let’s just get that out of the way—but the role they play comes directly from the feel of a classic Fania release. Could the horns actually be attributable to a single source? I doubt it, but more importantly, they operate only as a component of the song itself, placing this inspiration in a different musical context.

Sound Power

“Sound Power” fully embraces ‘sound’ as a fundamental musical object. Sounds in and of themselves can be understood as heads. The primary instrument I used on “Sound Power” is the sound generator of the 4|5 Ccls Heads Instrument. 4|5 Ccls is an arpeggiator modeled after John Coltrane’s sketches on the cycle of fifths. I tend to think of such sounds in relationship to the latter Coltrane years when he was using his instrument as a sound generator, clustering notes together and condensing melody.

Similarly, arpeggiators group notes into singular phrases which can be interpreted as heads. The head on “Sound Power” does not push the possibilities to the extreme, as Coltrane did; it remains constrained within a rhythmic framework. However, it shows the power of sound as fundamental. All of the drums, percussive elements, bass and harmonies flow from the head, accentuated by heavyweight vocal chops from the Heads Instrument scratch emulator.

Come Clean

The intro to “Come Clean” marks a turning point in the album. The first four tracks present are technical feats to illustrate the point. “Come Clean” doesn’t slack off. Musically this track is the closest to the “Blurred Lines” case; notably, other than the intro, it contains no sample. It’s head, however, comes from the Jeru the Damaja song “Come Clean” produced by DJ Premier. I did an extensive breakdown on the technical details of “Come Clean” on Avanturb a few years ago; my online installation shows how (and for how long) I have been contemplating this track. But to paraphrase the sample here, the true power of music is helping the listener realize the breadth of their own existence in this universe. My use of the song is very intentional, and I deliberately change its themes for the album.

For “Come Clean,” I worked with percussionists Zach and Claudia who studied in the Olatunji line of drumming. They noted the physical timing challenges getting used to the song’s unique head, but, once they locked in, the head held its own. That exemplifies the power of this means of composing – new original ideas which can push music’s possibilities.

As an artist, I advocate for the interpretation of copyright laws so that someone cannot sue because three notes of a song appear in one they own, or because a sound from the recording the record company convinced the artist to sign over to them for pennies was repitched and played into a melody. I know that arriving to music via these methods can push the traditions further, everything copyright laws were written to encourage. If we don’t change the way we think about copyright, the ability to create in this manner will be lost in litigation.

Heads comes out on April 1, 2015

—

Primus Luta is a husband and father of three. He is a writer and an artist exploring the intersection of technology and art, and their philosophical implications. He maintains his own AvantUrb site. Luta was a regular presenter for Rhythm Incursions. As an artist, he is a founding member of the collective Concrète Sound System. Recently Concréte released the second part of their Ultimate Break Beats series for Shocklee.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“SO! Reads: Jonathan Sterne’s MP3: The Meaning of a Format”-Aaron Trammell

“Remixing Girl Talk: The Poetics and Aesthetics of Mashups”-Aram Sinnreich

The Blue Notes of Sampling– Primus Luta

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Recent Comments