Listening to and as Contemporaries: W.E.B. Du Bois & Sigmund Freud

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

It has been an abundant decade-plus (!!!) since Alexander Weheliye’s Phonographies “link[ed] the formal structure of W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk to the contemporary mixing practices of DJs” (13) and we want to know how folks have thought about and listened with Du Bois in their work in the intervening years. How does Du Bois as DJ remix both the historiography and the contemporary praxis of sound studies? How does attention to Du Bois’s theories of race and sound encourage us to challenge the ways in which white supremacy has historically shaped American institutions, sensory orientations, and fields of study? What new futures emerge when we listen to Du Bois as a thinker and agent of sound?

Over the next two months, we will be sharing work that reimagines sound studies with Du Bois at the center. Pieces by Phillip Luke Sinitiere, Kristin Moriah, Aaron Carter-Ényì, Austin Richey, Julie Beth Napolin, and Vanessa Valdés, move us toward a decolonized understanding and history of sound studies, showing us how has Du Bois been urging us to attune ourselves to it. To start the series from the beginning, click here.

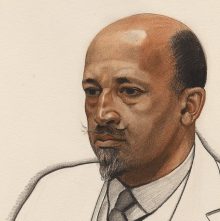

Readers, today’s post (the first of an interwoven trilogy of essays) by Julie Beth Napolin explores Du Bois and Freud as lived contemporaries exploring entangled notions of melancholic listening across the Veil.

–Jennifer Lynn Stoever and Liana Silva, Eds.

When W.E.B. Du Bois began the first essay of The Souls of Black Folk (1903) with a bar of melody from “Nobody Knows the Trouble I See,” he paired it with an epigraph taken from a poem by Arthur Symons, “The Crying of Water”:

O water, voice of my heart, crying in the sand,

All night long crying with a mournful cry,

As I lie and listen, and cannot understand

The voice of my heart in my side or the voice of the sea,

O water, crying for rest, is it I, is it I?

All night long the water is crying to me.

A listener, the poem’s speaker can’t be sure of the source of the sound, whether it is inward or outward. Something of its sound is exiled and resonates with Symons’ biographical position as a Welshman writing in English, an imperial tongue. At the heart of the poem is a meditation on language, communication, and listening. Personified, the water longs to be understood and sounds out the listener’s own interiority that struggles to be communicated. The poem’s speaker hears himself in the water, but he is nonetheless divided from it. If he could understand the source of the sound in a suppressed or otherwise unavailable memory, the speaker might be put back together. But listening all night long, that understanding does not come.

Démontée, Image by Flickr User Alain Bachellier

Together, the poem and song serve as a circuitous opening to Du Bois’ “Of Our Spiritual Strivings,” an essay that grounds itself in Du Bois’ training as a sociologist to detail “the color line,” which Du Bois takes to be the defining problem of 20th century America. The color line is not simply a social and economic problem of the failed projects of Emancipation and Reconstruction, but a psychological problem playing out in what Du Bois is quick to name “consciousness.” As the first African American to receive a PhD from Harvard in 1895, Du Bois had studied with psychologist William James, famous for coining the phrase “the stream of thought” in his modernist opus, The Principles of Psychology (1890). In her study of pragmatism and politics in Du Bois, Mary Zamberlin describes how James encouraged his students to listen to lectures in the way that one “receives a song” (qtd. 81). In his techniques of writing, Du Bois adopts and reinforces the paramount place of intuition and receptivity in James’ thought to conjoin otherwise opposed concepts. Demonstrated by the opening epigraphs themselves, Du Bois’ techniques often trade in a lyricism that stimulates the reader’s multiple senses.

I argue that Du Bois surpasses James by thinking through listening consciousness in its relationship to what we now call trauma. While I will remark upon the specific place of the melody in Du Bois’ propositions, I want to focus on the more generalized opening of his book in the sounds of suffering, crying, and what Jeff T. Johnson might call “trouble.” The contemporary understanding of trauma, as a belated series of memories attached to experiences that could not be fully grasped in their first instance, comes to us not from the scientific discipline of psychology, but rather psychoanalysis.

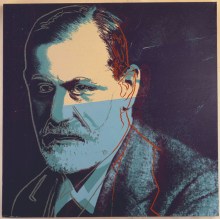

Among the field’s first progenitors, Sigmund Freud, was a contemporary of Du Bois. Though trained as a medical doctor, Freud sought to free the concept of the psyche from its anatomical moorings, focusing in particular on what in the human subject is irrational, unconscious, and least available to intellectual mastery. His thinking of trauma became most pronounced in the years following WWI, when he observed the consequences of shell-shock. Freud discovered a more generalizable tendency in the subject to go over and repeat painful experiences in nightmares. Traumatic repetition, he noted, is a subject struggling to remember and to understand something incredibly difficult to put into words. At the heart of Freud’s methods, of course, was listening and the observations it afforded, grounding his famous notion of the “talking cure.” Because trauma is so often without clear expression, Freud listened to language beyond meaning, beyond what can be offered up for scientific understanding.

Image by Flicker User Khuroshvili Ilya

The beginning of Souls, along with its final chapter on “sorrow songs,” slave song or spirituals, tells us that Du Bois’ project shared that same auditory core. Du Bois was listening to consciousness, that is, developing a theory of a listening (to) consciousness in an attempt to understand the trauma of racism and the long, drawn-out historical repercussions of slavery. Importantly, however, Du Bois’ meditation on trauma precedes Freud’s. But Du Bois’ thinking also surpasses Freud in beginning from the premise that trauma is the sine qua non of theorizing racism, which makes itself felt not only outwardly in social and economic structures, but inwardly in consciousness and memory.

Du Bois claimed that he hadn’t been sufficiently Freudian in diagnosing white racism as a problem of irrationality. He didn’t mean by this that Freud himself made such a diagnosis, but rather that Freud was correct in refusing to underestimate what is least understandable about people. Freud’s thinking, however, remained mired in racist thinking of Africa. Though he claimed to discover a universal subject in the structure of the psyche—no one is free from the unconscious—racist thinking provided the language for the so-called “primitive” part of the human being in drives. This primitivism shaped Freud’s myopic thinking of female sexuality, famously remarking that female sexuality is the “Dark Continent,” i.e. unavailable to theory. Freud drew the phrase from the imperialist travelogues of Henry Morton Stanley in the same moment that Du Bois was turning to Africa to find what he called, both with and against Hegel, a “world-historical people.” As I argue, Du Bois found in the music descended from the slave trade not only a “gift” and “message” to the world, but the ur-site for theorizing trauma.

Ranjana Khanna has shown how colonial thinking was the precondition for Freudian psychoanalysis. Anti-colonial psychiatrist Frantz Fanon, for example, both took up and resisted Freud when he elaborated the effects of racism as the origin of black psychopathology, i.e. feelings of being split or divided. Du Bois, like Fanon after him, was hearing trauma politically as a structural event. The complex intellectual biography of Du Bois, which includes a time of studying (in German) at Berlin’s Humboldt University, mandated that he took from European philosophical interlocutors what he needed, creating a hybrid yet decidedly new theory of listening consciousness. That hybridity is exemplified by the opening of his book, an antiphony between two disparate sources bound to each other across the Atlantic through what I will call hearing without understanding. In this post, I ask what Du Bois can tell us about psychoanalytic listening and its ongoing potential for sound studies and why Freud had difficultly listening for race.

***

“Before the Storm,” Image by Flickr User Marina S.

“Psychoanalysis . . . , more than any twentieth-century movement,” writes Eli Zaretsky in Political Freud, “placed memory at the center of all human strivings toward freedom” (41). He continues, “By memory I mean no so much objective knowledge of the past or history but rather the subjective process of mastering the past so that it becomes part of one’s identity.” In 1919, Freud gave a name to the experience resounding for Du Bois in Symons’ poem “The Crying of Water:” “melancholia.” Unlike mourning after the death of a loved one, whose aching and cries pass with time, melancholia is an ongoing, integral part of subjects who have lost more inchoate things, such as nation or an ideal. This loss, Freud contended, could in fact be constitutive of identity, or the “ego,” Latin for “I” (“is it I? Is it I?” Symons asks). In mourning, one knows what has been lost; in melancholia, one can’t totally circumscribe its contours.

Zaretsky details the way that Freudianism, particularly after its rapid expansion in the US after WWI, became a resource for the transformation of African American political and cultural consciousness, playing a pronounced role in the Harlem Renaissance, the Popular Front, and anti-imperialist struggles. Zaretsky rightly positions Du Bois and his 1903 text as the beginning of a political and cultural transformation, but it is an anachronism to suggest that Freudianism contributed to Du Bois’ early work. Not only does Du Bois’ analysis of “The Crying of Water” predate Freud’s “Mourning and Melancholia” by nearly two decades, the two thinkers were contemporaries. In the years that Freud was writing his letters to Wilhelm Fliess, which became the body of his first book, The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), Du Bois was compiling his previous publications for The Souls of Black Folk, along with writing a new essay to conclude it, “The Sorrow Songs,” a sustained reflection on melancholia and its cultural reverberations in song. 1903 is the year of Souls compilation, not composition.

Du Bois’ thinking of a racialized listening consciousness is not only contemporary to Freud, but also fulfills and outstrips him. To approach Du Bois and Freud as contemporaries involves positioning them as listeners on different, but not opposing sides of what Du Bois calls the “Veil.” It is the psychological barrier traumatically instantiated by racialization, which Du Bois famously describes in the first chapter of Souls. The Veil, Jennifer Stoever describes, is both a visual and auditory figure, the barrier through which one both sees and hears others.

To better define the Veil, Du Bois—like Frederick Douglass before him—returns to a painful childhood scene that inscribed in his memory the violence of racial difference and social hierarchy. Early works of African American literature often turn to memoir, writing their elided subjectivity into history. But we miss something if we don’t recognize there a proto-psychoanalytic gesture. In the middle of a sociological, political essay, Du Bois writes of the painful memory of a little white girl rejecting his card, a gift. In this, we can recognize the essential psychoanalytic gesture of returning to the traumatic past of the individual as a forge for self-actualization in the present.

“Storm Coming Our Way” by Flickr User John

As Paul Gilroy has described, Du Bois’ absorption of Hegel’s thought while at Humboldt cannot be underestimated, particularly in terms of the famous master-slave dialectic. In this dialectic, the slave-consciousness emerges as victorious because the master depends on him for his own identity, a struggle that Hegel described as taking place within consciousness. Like Hegel, Zaretsky notes, Du Bois understood outward political struggle to be bound to “internal struggle against . . . psychic masters” (39). I would state this point differently to note that Du Bois’ traumatic experience as a raced being had already taught him the Hegelian maxim: the smallest unit of being is not one, but two. For Hegel, the slave knows something the master doesn’t: I am only complete to the extent that I recognize the other in myself and that the other recognizes me in herself. That is the essential lesson that an adult Du Bois gleans from the memory of the little girl who will not listen to him. He recognizes that she, too, is incomplete.

The essential difference between psychoanalysis and the Hegelian thrust of Du Bois’ essay, however, is that while a traditional analysand seeks individual re-making of the past—not only childhood, but a historical past that shapes an ongoing political present– Du Bois emphasizes the collective and in ways that cannot be reduced to what Freud later calls the “group ego.” If we restore the place of Du Bois at the beginnings of psychoanalysis and its ways of listening to ego formation, then we find that race, rather than being an addendum to its project, is at its core.

We can begin by turning to a paradigmatic scene for psychoanalytic listening, the one that has most often been taken up by sound studies: the so-called “primal scene.” In among the most famous dreams analyzed by Freud, Sergei Pankejeff (a.k.a. the “Wolf Man”) recalls once dreaming that he was lying in bed at night near a window that slowly opened to reveal a tree of white wolves. Silent and staring, they sat with ears “pricked” (aufgestellt). Pricked towards what? The young boy couldn’t hear, but he sensed the wolves must have been responding to some sound in the distance, perhaps a cry.

“The Wolf Man’s Dream” by Sergei Pankejeff, Freud Museum, London

In “The Dream and the Primal Scene” section of “From the History of An Infantile Neurosis” (1914/1918), Freud concluded that the dream was grounded in the young boy’s traumatic experience of witnessing his parents having sex. Calling this the “primal scene,” Freud conjectured that there must have been an event of overhearing sounds the young boy could not understand. In the letters he exchanged with Fliess, Freud had begun to attend to the strange things heard in childhood as the basis for fantasy life and with it, sexuality.

The primal scene is therefore crucial for Mladen Dolar’s theory in A Voice and Nothing More when he pursues the implications of an unclosed gap between hearing and understanding. In the Wolf Man’s case, it is impossible, Freud writes, for “a deferred revision of the impressions…to penetrate the understanding.” In Dolar’s estimation, the deferred relation between hearing and understanding defines sexuality and is the origin of all fantasy life. This gap in impressions cannot be closed or healed, and, for Jacques Lacan it also orients the failure of the symbolic order to bring the imaginary order to language. From this moment forward, psychoanalytic theory argues the subject is “split,” listening in a dual posture for the threat of danger and the promise of pleasure. Following Lacan, Dolar, Michel Chion, and Slavoj Žižek return to the domain of infantile listening—listening that occurs before a person has fully entered into speech and language—to explain the effects of the “acousmatic,” or hearing without seeing.

After Freud, the phrase “primal scene” has taken on larger significance as a traumatic event that, while difficult to compass, nonetheless originates a new subject position that makes itself available to a collective identity and identification. The original meaning of hearing sexual and libidinal signals without understanding them, I would suggest, holds sway. Psychoanalytic modes of listening, particularly if restored to its political origins in racism, offer resources for what it means to listen beyond understanding, but such thinking of race immediately folds into intersectional thinking of gender and sexuality. Consider the place of the traumatic memory of the little girl who rejects the card. In The Sovereignty of Quiet, Kevin Quashie returns to Du Bois’ primal scene to note how the scene takes place in silence, for she rejects it, in Du Bois’ terms, “with a glance.” I want to expand upon this point to note that where there is silence, there is nonetheless listening. Du Bois is listening for someone who will not speak to him; he desires to be listened to and the card—a calling card—figures a kind of address.

Vintage Calling Card, Image by Flickr User Suzanne Duda

It has gone largely unnoticed that, to the extent that the scene is structured by the master-slave dialectic, it is also structured by desire. This scene of trauma is shattering for both boy and girl. The desire coursing through the scene is suppressed in Du Bois’ adult memory in favor of its meaning for him as a political subject. What would it mean to recollect, on both sides, the trace of sexual (and interracial) desire? In “Resounding Souls: Du Bois and the African American Literary Tradition,” Cheryl Wall notes the scant place for black women in the political imaginary of this text. This suppression, I would argue, already begins in the memory of the girl who appears under the sign of the feminine more generally. The fact that she is white, however, casts a greater taboo over the scene and therefore allows more for a suppression of sexuality in his memory. Du Bois emerges as a political agent disentangled from black women—with one notable exception, the maternal, and this exception demands that we listen with ears pricked to “The Sorrow Songs,” as Du Bois’ early contribution to the psychoanalytic theory of melancholia.

Next week, part two will further explore The Souls of Black Folk as a “displaced beginning of psychoanalytic modes of listening,” emphasizing the African melodies once sung by his grandfather’s grandmother that Du Bois’s hears as a child, as “a partial memory and a mode of overhearing.”

—

Featured Images: “Nobody Knowns the Trouble I See” from The Souls of Black Folk, Chapter 1, “W.E.B. Du Bois” by Winold Reiss (1925), “Sigmund Freud” by Andy Warhol (1962)

—

Julie Beth Napolin is Assistant Professor of Literary Studies at The New School, a musician, and radio producer. She received a PhD in Rhetoric from the University of California, Berkeley. Her work participates in the fields of sound studies, literary modernism and aesthetic philosophy, asking what practices and philosophies of listening can tell us about the novel as form. She served as Associate Editor of Digital Yoknapatawpha and is writing a book manuscript on listening, race, and memory in the works of Conrad, Du Bois, and Faulkner titled The Fact of Resonance. Her work has appeared in qui parle, Fifty Years After Faulkner (ed. Jay Watson and Ann Abadie), and Vibratory Modernism (ed. Shelley Trower and Anthony Enns).

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“A Sinister Resonance”: Joseph Conrad’s Malay Ear and Auditory Cultural Studies–Julie Beth Napolin

“Scenes of Subjection: Women’s Voices Narrating Black Death“–Julie Beth Napolin

Unsettled Listening: Integrating Film and Place — Randolph Jordan

“Music More Ancient than Words”: W.E.B. Du Bois’s Theories on Africana Aurality

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

It has been an abundant decade-plus (!!!) since Alexander Weheliye’s Phonographies “link[ed] the formal structure of W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk to the contemporary mixing practices of DJs” (13) and we want to know how folks have thought about and listened with Du Bois in their work in the intervening years. How does Du Bois as DJ remix both the historiography and the contemporary praxis of sound studies? How does attention to Du Bois’s theories of race and sound encourage us to challenge the ways in which white supremacy has historically shaped American institutions, sensory orientations, and fields of study? What new futures emerge when we listen to Du Bois as a thinker and agent of sound?

Over the next two months, we will be sharing work that reimagines sound studies with Du Bois at the center. Pieces by Phillip Luke Sinitiere, Kristin Moriah, Aaron Carter-Ényì, Austin Richey, Julie Beth Napolin, and Vanessa Valdés, move us toward a decolonized understanding and history of sound studies, showing us how has Du Bois been urging us to attune ourselves to it. To start the series from the beginning, click here.

Readers, today’s post by Aaron Carter-Ényì delineates two central strands in Du Bois’s work that have proven key to what we now call sound studies–the historical and affective meanings that sound carries as well as its ability to travel great distances through time and space.

–Jennifer Lynn Stoever and Liana Silva, Eds.

I know little of music and can say nothing in technical phrase, but I know something of men, and knowing them, I know that these songs are the articulate message of the slave to the world. – W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903, p. 253)

W. E. B. Du Bois claimed to “know little of music,” yet his writings offer profound insights into aurality, foreshadowing the transdisciplinary of sound studies, by connecting language, music, sonic environments and aural communication. Du Bois published the souls of The Souls of Black Folk in 1903, less than a decade after becoming the first African American to receive a PhD from Harvard in 1895. In it, he addresses the color line, reflected in the policy of “separate but equal,” forming arguments that continue in Black Reconstruction in America. He also introduces themes that reappear in his later works including The World and Africa (1947), which formed the seeds of Afropolitanism and many modes of enquiry of Sound Studies. This short essay explores two concepts in Du Bois’s writings: that melodies may last longer than lyrics as cultural retentions; and, that drummed language may travel further than spoken language as communication.

By the time Du Bois published The Souls of Black Folk, what he termed the “Sorrow Songs” (alternatively Slave Songs or Spirituals) had entered the popular canon of American song. As incipits (or epigraphs) for each essay in the book, he entered the songs into a new literary and scholarly canon, ultimately changing the concept of what a book could be by fusing language and music in a new way. Even in a divided society following the U.S. government’s disinvestment in Reconstruction and the sharp uptick in lynching and other forms of racial terror, the “Negro folk-song” could not help but have a profound impact “as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side the seas” (Souls XIV), particularly due to the efforts of Fisk’s Jubilee Singers. Du Bois’s choice to include musical transcriptions without lyrics at the opening of each essay in Souls reflects a view of melodies as having a life–and a value– of their own.

Du Bois paired a quote from “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage ” by Lord Byron with a musical citation from the African American spiritual “The Great Camp Meeting” to open Chapter III, “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others.”

Although Du Bois’s work quite clearly accounts for the development of what has usually been called the African American oral tradition, the concept of an oral tradition is credited to Harvard comparative literature scholars Milman Parry and Albert Lord, who popularized the term in American scholarship by establishing a binary theory of orality and literacy, that not only pitted the two against each other, but implied that they were hierarchical, evolutionary phases of “culture” (1960). This divide both widened and became more nuanced with Walter Ong’s recognition of “secondary orality” (1982), acknowledging that aspects of orality persist in literate societies.

But much earlier than these texts, Du Bois offers an alternate theory of how orality and literacy work, and even concepts similar to secondary orality, in the last essay of Souls, “XIV On the Sorrow Songs.” Notably, he describes his earliest experience with African music via a song that “travelled down” from his “grandfather’s grandmother”:

The songs are indeed the siftings of centuries; the music is far more ancient than the words, and in it we can trace here and there signs of development. My grandfather’s grand-mother was seized by an evil Dutch trader two centuries ago; and coming to the valleys of the Hudson and Housatonic, black, little, and lithe, she shivered and shrank in the harsh north winds, looked longingly at the hills, and often crooned a heathen melody to the child between her knees, thus:

The child sang it to his children and they to their children’s children, and so two hundred years it has travelled down to us and we sing it to our children, knowing as little as our fathers what its words may mean, but knowing well the meaning of its music (254).

Du Bois makes no mention of a spoken oral tradition throughout Souls. In fact, quite the contrary. In this passage, he implicitly argues it is not the meaning of the words, but the meaning of the music that survived the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Instead of an “oral tradition”, Du Bois identifies four steps in the development of American Sorrow Songs: (1) African; (2) “Afro-American”; (3) blending of “Negro and Caucasian” (a creolization); and (4) songs of white America influenced by the Sorrow Songs (256). The search for continuity between African and American culture has been a quest for many, including African-born scholars such as Lazarus Ekwueme. It is clear that melody (both pitch and rhythm) is the most idiosyncratic element of a piece, more so than lyrics, and is the most durable when a people and their culture experience extreme duress. As language (and certainly the meaning of the language) can fade (or be violently submerged) in diaspora, melodies can often hold fast, and be held on to.

At an early date (1903), Du Bois already arrives at a point that is now a consensus: the Gullah-Geechee communities of the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia have closely retained African practices, such as the ring shout.

Gullah-Geechee ring shout performed by McIntosh County Shouters (Carter-Ényì, Hood, Johnson, Jordan and Miller 2018)

Du Bois states that the Sea Island people are “touched and moulded less by the world about them than any others outside the Black Belt” (251–2). The Language You Cry In (1988), traces a Gullah song passed down back to its origins in Sierra Leone. Though separated by 200 years and 5000 miles, the melody was immediately recognizable to Baindu Jabati, a woman of the village, Senehum Ngola, even the lyrics were “strikingly similar.”

Sheet Music, “Old Folks At Home,” A project of the Digital Scriptorium Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, Duke University

The Gullah-Geechee are exceptional because of their linguistic retentions, documented by Lorenzo Dow Turner in his 1949 book. The preservation of linguistic features was possible because of relative isolation, but as Du Bois notes, this source of African music is fundamental to American music in steps (2), (3) and (4), of which he offers famous examples of each. It is the recognition of the crossing of the African and African-American influence across the racial divide into the music of white America, in songs such as Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home” (more popularly known as “Swanee River”) that was the most controversial. Du Bois approaches this matter cautiously: “One might go further and find a fourth step in this development…” (256), but then goes full force: “a mass of music in which the novice may easily lose himself and never find the real Negro melodies” (257).

Racist musicologist George Pullen Jackson (1874-1953) fought hard against the position that white hymnody had been influenced by black spirituals for much of his career. In “White and Negro spirituals, their life span and kinship” (1944), he argued just the opposite, that black spirituals were derivative of white hymnody and conducted an early corpus study to prove it. William H. Tallmadge, in “The Black in Jackson’s White Spirituals” (1981), summarizes Jackson’s findings:

Jackson, after examining 562 white items and 892 black items, found only 116 pairs which he thought demonstrated tune similarities, and of these 116, only 70 pairs actually prove to have had a valid melodic relationship… These seventy items represent slightly less than eight percent of the 892 black spirituals (150).

Jackson could not find the empirical support for his claim to of primacy (perhaps supremacy) of white spirituals, even with some ample confirmation bias. In fact, his findings fit well into Du Bois’s account, particularly his identification of step 3 in the development of the Sorrow Songs: “blending of Negro music with the music heard in the foster land” (256). Essentially, it took a nearly a century for musicology to recognize what Du Bois laid out in 1903.

The aural tradition Du Bois describes, which includes various versions of songs and the steps of sorrow song development, is more sympathetic to Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s concept of “orature” than the Parry/Lord dichotomy. In “Notes towards a Performance Theory of Orature” (2007), Thiong’o points out that:

What is often arrested in writing is a particular version, a particular rendering, … as performed by a particular performers at a particular moment. Nature, then, in orature manifests itself as a web of connections of mutual dependence … in active communications within themselves and with others (5).

For example, the black and white spirituals with similar tunes in Jackson’s corpus both are and are not the same, which challenges the very notion of intellectual property (IP), and the flawed IP debate over spirituals that Jackson pursued. Even in a segregated society, under which racist laws separated the performers, a mutual dependence developed between black and white spirituals. Despite the affinity of the melodies and common heritage in the aural culture (and perhaps even common sources in either Africa or Europe), divisions were articulated in writing, through different hymnbooks and different words, once again supporting the veracity of Du Bois’s claim that the “music is far more ancient than the words.”

Waves on the Ghanaian Shore, Image by Flickr User Yenkassa (CC BY 2.0)

Later in his life, Du Bois’s attention turned more and more toward Africa. In The World and Africa (1947), he confronts colonialism and Eurocentric history, foreshadowing Afrocentrism and to some extent Afropolitanism. He also, very briefly, reprises his discussion of aurality, citing German musicologist and father of organology, Erich von Hornbostel, as affirmation of the virtues of both African and African American music from the 1928 article “African Negro Music”:

The African Negroes are uncommonly gifted for music-probably, on an average, more so, than the white race. This is clear not only from the high development of African music, especially as regards polyphony and rhythm, but a very curious fact, unparalleled, perhaps, in history, makes it even more evident; namely, the fact that the negro slaves in America and their descendants, abandoning their original musical style, have adapted themselves to that of their white masters and produced a new kind of folk-music in that style. Presumably no other people would have accomplished this. (In fact the plantation songs and spirituals, and also the blues and rag-times which have launched or helped to launch our modern dance-music, are the only remarkable kinds of music brought forth in America by immigrants (60).

Du Bois studied in Germany from 1892–94 before attending Harvard. According to Kenneth Barkin (2005), Du Bois’s “affection” for Imperial Germany has “remained a puzzle to historians” (285). Hornbostel too had a complicated relationship to Germany: though celebrated in his home country for much of his life, in 1933 he was forced into exile because his mother was Jewish; he died in 1935. The passage Du Bois cites from Hornbostel echoes some aspects of Souls XIV Sorrow Songs, particularly the centrality of the spirituals in American culture, but not all. In particular, “abandoning their original musical style … to that of their white masters” is incongruent with Du Bois’s earlier perspective. Though Hornbostel is clearly impressed with the musicality of black people(s), Hornbostel’s summary conclusions stated at the beginning of the same article do not mesh with Du Bois’s own (more insightful) work in Souls: “African and (modern) European music are constructed on entirely different principles, and therefore they cannot be fused into one, but only the one or the other can be used without compromise” (30).

Unfortunately, Du Bois does not contest Hornbostel with his narrative of continuity and “steps” of development from Souls. Du Bois recognized both the happenings and possibilities of creolization and syncretism in black culture of which Hornbostel only captures glimpses. Ultimately, despite a generally positive perspective on black music, Hornbostel’s position is one of not only continental, but racial, division, promoting segregation of musical practice as the only way. It is disconcerting that Du Bois cites this article and Hornbostel as a musical expert with its main argument when Du Bois identified the color line as the singular issue of the twentieth century.

In The World and Africa, Du Bois goal is a bit different: in the pursuit of repositioning Africa and moving towards both a corrected history and post-colonial future, there were stranger bedfellows than Hornbostel. A more pristine vision of recasting Africa and Africana aurality is found on the same page (99), in Du Bois’s mention of an astonishing form of music as communication, the talking drum: “The development of the drum language by intricate rhythms enabled the natives not only to lead in dance and ceremony, but to telegraph all over the continent with a swiftness and precision hardly rivaled by the electric telegraph” (99).

The recent intellectual current within African studies, Afropolitanism, is embodied in Du Bois’s juxtaposition of African tradition with modernity. A recent book on West African talking drums by Amanda Villepastour, Ancient Text Messages of the Yorùbá bàtá drum also draws an analogy to telecommunication. While Du Bois’s brief 1947 account is only a single sentence, Villepastour’s lengthy 2010 account confirms Du Bois conjecture was not a metaphor or empty comparison, the talking drum and telegraph share the same utility, and while we are keeping track, the talking drum came first and is a lot more efficient in terms of infrastructure.

Yorùbá talking drummers in Ọ̀yọ́, Nigeria (Carter-Ényì 2013)

For those unfamiliar with them, here are some rough calculations regarding how talking drums work. Singing or shouting is about 80 decibels (dB) at one meter. Drumming is over 100 dB at one meter. This 20 dB differential means that a speech surrogate (like a talking drum) could travel up to 10 times the distance under the same environmental conditions. With those intensities at the source, a loud voice could travel one kilometer before becoming inaudible (at around 20 dB), while a drum could reach 10 km, easily communicating with the next village.

Hausa Talking Drum, Image by African Studies Library BU (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Within a regional network of drummers that “speak” the same language—such as in the Yorùbá-speaking region of southwest Nigeria—long distance communication was possible, and much earlier than the telegraph. A recent study (2018) by Frank Seifert and his colleagues on Amazonian Bora drumming, “Reducing language to rhythm,” finds minute timing variations represent the placement of consonants suggesting there is detail in speech surrogacy, beyond the representation of lexical tone previously documented. Seifert’s findings suggest that the “precision” Du Bois described is exactly what talking drummers have (throughout the Global South). Now the “swiftness” part may have been a bit exaggerated (electric signals travel much faster than sound waves).

Du Bois’s practiced a transdisciplinary study of sound and understood Africa as Afropolitan long before most of the West. In addition to foreshadowing the interdisciplinary moves of sound studies—which also connects sound to speech to music and examines their coexistence—Du Bois’s thinking also prefigures the current intellectual (and urban-cultural) vogue of Afropolitanism, which has to some extent displaced the Pan-African movement that drew Du Bois to Ghana.In a 2016 interview, Achille Mbembe positions Afropolitanism as a way “in which Africans, or people of African origin, understand themselves as being part of the world rather than being apart.” Much like the African cultures he first encountered in melody in the nineteenth century and then heard firsthand as a contemporary when he moved to Ghana in 1961, Du Bois heard beyond Eurocentric disciplinary divides of music and language that served to portray African cultures as somehow always already outside of modernity, yet not the right color of “ancient.” Du Bois wholeheartedly believed music could change the narrative of Black life, history and culture, a message first crooned to him as a child between his grandmother’s knees, to which he never stopped listening.

Housatonic River, Great Barrington Massachusetts, W.E.B. Du Bois’s Home Town. Image by Flickr User Criana, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

—

Featured Image: Brooklyn African Festival Drum, 2010, Image by Flickr User Serge de Gracia (CC BY-NC 2.0)

—

Aaron Carter-Ényì teaches music theory, class piano, and music appreciation in Morehouse’s Department of Music. He holds a PhD from Ohio State University (2016), was a Fulbright Scholar to Nigeria in 2013, and is a 2017 fellow of the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS). Recent scholarship appears in Africa (Journal of the International African Institute), Ethnomusicology, Music Theory Online, Oxford Handbook of Singing and Tonal Aspects of Languages; or is forthcoming in Performance Research and Sounding Out! He is the director of the interdisciplinary Africana Digital Ethnography Project (ADEPt) and is currently developing the Video-EASE Toolbox and ATAVizM. During the summer, he is a STEAM instructor for federally-sponsored student enrichment programs including MSEIPand iSTEM for which he provides workshops and courses in the Morehouse Makerspace.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Music Meant to Make You Move: Considering the Aural Kinesthetic–Imani Kai Johnson

Black Mourning, Black Movement(s): Savion Glover’s Dance for Amiri Baraka –Kristin Moriah

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

- Finding Resonance, Finding María Lugones

- Press Play and Lean Back: Passive Listening and Platform Power on Nintendo’s Music Streaming Service

- “A Long, Strange Trip”: An Engineer’s Journey Through FM College Radio

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments