The Braids, The Bars, and the Blackness: Ruminations on Hip Hop’s World War III – Drake versus Kendrick (Part One)

A Conversation by Todd Craig and LeBrandon Smith

By now, it’s safe to say very few people have not caught wind of the biggest Hip-Hop battle of the 21st century: the clash between Kendrick Lamar and Drake. Whether you’ve seen the videos, the memes or even smacked a bunch of owls around playing the video game, this battle grew beyond Hip Hop, with various facets of global popular culture tapped in, counting down minutes for responses and getting whiplash with the speed of song drops. There are multiple ways to approach this event. We’ve seen inciteful arguments about how these two young Black males at the pinnacle of success are tearing one another down. We also acknowledge Hip Hop’s long legacy of battling; the culture has always been a “competitive sport” that includes “lyrical sparring.”

This three-part article for Sounding Out!’s Hip Hop History Month edition stems from a longer conversation with two co-authors and friends, Hip Hop listeners and aficionados, trying to make sense of all the songs and various aspects of the visuals. This intergenerational conversation involving two different sets of Hip Hop listening ears, both heavily steeped in Hip Hop’s sonic culture, is important. Our goal here is to think through this battle by highlighting quotes from songs that resonated with us as we chronicled this moment. We hope this article serves as a responsible sonic assessment of this monumental Hip Hop episode.

First things first: what’s so intergenerational about our viewpoints? This information provides some perspective on how this most recent battle resonated with two avid Hip Hop listeners and cultural participants.

LeBrandon is a 33 year old Black male raised in Brooklyn and Queens, New York. He is an innovative curator and social impact leader. When asked about the first Hip Hop beef that impacted him, LeBrandon said:

The first Hip-Hop battle I remember is Jay x Nas and mainly because Jay was my favorite rapper at the time. I was young but mature enough to feel the burn of “Ether.” It’s embarrassing to say now, but truthfully I was hurt—as if “Ether” had been pointed at me. “Ether” is a masterclass in Hip Hop disrespect but the stanza that I remember feeling terrible about was “I’ll still whip your ass/ you 36 in a karate class?/ you Tae-bo hoe/ tryna work it out/ you tryna get brolic/ Ask me if I’m tryna kick knowledge/ Nah I’m tryna kick the shit you need to learn though/ that ether, that shit that make your soul burn slow.” MAN. I remember thinking, is Jay old?! Is 36 old?! Is my favorite rapper old?! Why did Nas say that about him? I should reiterate I am older now and don’t think 36 is old, related or unrelated to Hip Hop. Nas’s gloves off approach shocked me and genuinely concerned me. But I’m thankful for the exposure “Ether” gave me to the understanding that anything goes in a Hip-Hop battle.

Todd is a Black male who grew up in Ravenswood and Queensbridge Houses in Long Island City, New York. Todd is about 15 years older than LeBrandon, and is an associate professor of African American Studies and English. Todd stated:

The first battle that engaged my Hip Hop senses was the BDP vs. Juice Crew battle –specifically “The Bridge” and “The Bridge is Over.” The stakes were high, the messages were clear-cut, and the battle lines were drawn. I lived in Ravenswood but I had family and friends in QB. And “The Bridge” was like a borough anthem. Even though MC Shan was repping the Bridge, that song motivated and galvanized our whole area in Long Island City. This was the first time in Hip Hop that I recall needing to choose a side. And because I had seen Shan and Marley and Shante in real life in QB, the choice was a no-brainer. That battle led me to start recording Mr. Magic and Marley Marl’s show on 107.5 WBLS, before even checking out what Chuck Chillout or Red Alert was doing. As I got older, it would sting when I heard “The Bridge is Over” at a club or a party. And when I would DJ, I’d always play “The Bridge is Over” first, and follow it up with either “The Bridge” or another QB anthem, like a “Shook Ones Pt. 2” or something.

We both enter this conversation agreeing this battle has been brewing for about ten years, however it really came to a head in the Drake and J. Cole song, “First Person Shooter.” Evident in the song is J. Cole’s consistent references to the “Big Three” (meaning Kendrick Lamar, Drake and J. Cole atop Hip-Hop’s food chain), while Drake was very much focused on himself and Cole. It is rumored that Kendrick was asked to be on the song; his absence without some lyrical revision by Cole and Drake, seems to have led to Kendrick feeling snubbed or slighted in some way. This song gets Hip Hop listeners to Kendrick’s verse on the Future and Metro Boomin’ song “Like That” where Kendrick sets Hip Hop ablaze with the simple response: “Muthafuck the Big Three, nigguh, it’s just Big Me” – a moment where he “takes flight” and avoids the “sneak dissing” that he asserts Drake has consistently done.

We both agreed that Drake’s initial full-length entry into this battle, “Push Ups,” was the typical diss record we’d expect from him. Whether in his battle with Meek Mill or Pusha T, Drake’s entry follows the typical guidelines for diss records: it comes with a series of jabs at an opponent, which starts the war of words. The goal in a battle is always to disrespect your opponent to the fullest extent, so we find Drake aiming to do just that. We both noticed those jabs, most memorably is “how you big steppin’ with some size 7 men’s on.” We also noticed Drake’s misstep by citing the wrong label for Kendrick when he says “you’re in the scope right now” – alluding to Kendrick Lamar being signed to Interscope – even though neither Top Dog Entertainment (TDE) nor PGLang are signed to Interscope Records. Drake’s lack of focus on just Kendrick would prove a mistake: he disses Metro Boomin, The Weeknd, Rick Ross, and basketball player Ja Morant in “Push Ups.”

While we agree that in a rap battle, the goal is to disrespect your opponent at the highest level, we had differing perspectives on Drake’s second diss track “Taylor Made Freestyle.” LeBrandon felt this song landed because it took a “no fucks” approach to the battle. Regardless of how one may feel about Drake’s method of disrespect (by using AI), the message was loud and inescapable. LeBrandon highlighted the moment when AI Tupac says “Kendrick we need ya!”; outside of how hilarious this line is, Drake dissing Kendrick by using Tupac’s voice – a person with a legacy that Kendrick holds in the highest esteem – further established that this would be no friendly sparring match. Not only did Drake disrespect a Hip Hop legend with this line and its delivery, but an entire coast. The track invokes the spirit of a deceased rapper, specifically one whose murder was so closely connected to Hip Hop and authentic street beef. This moment was a step too far for Todd, who lived through the moment when both 2Pac and Biggie were murdered over fabricated beef.

Furthermore, LeBrandon pointed to the ever controversial usage of AI in Hip Hop, something Drake’s boss, Sir Lucian Grainge, recently condemned (especially when Drake, himself, condemns the AI usage of his own voice). By blatantly ignoring the issues and respectability codes the Hip Hop community should and does have with these ideas, Drake’s method of poking fun at his opponent was glorious. It was uncomfortable, condescending and straight-up gangsta. It also showcased Drake’s everlasting creative ability and willingness to take a risk. Todd acknowledged a generationally tinged viewpoint: this might also be a misstep for Drake because he used Snoop Dogg’s voice as well. Not only is Snoop alive, but Snoop was instrumental in passing the West Coast torch and crown to Kendrick. So when Drake uses an AI Snoop voice to spit “right now it’s looking like you writin’ out the game plan on how to lose/ how to bark up the wrong tree and then get your head popped in a crowded room,” it strikes at the heart of the AI controversy in music. This was not Snoop’s commentary at all. We both agree, however, that the “bark up the wrong tree” and “Kendrick we need ya” lines came back to haunt Drake. We also agree that dropping “Push Ups” and “Taylor Made Freestyle” is Drake’s battle format, hoping that he can overwhelm an opponent with multiple songs in rapid fire.

Todd and LeBrandon’s Hip Hop History Month play-by-play continues on November 11th with the release of Part 2! Return for “Euphoria” and stay until “6:16 in LA.”

—

Our Icon for this series is a mash up of “Kendrick Lamar (Sziget Festival 2018)” taken by Flickr User Peter Ohnacker (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) and “Drake, Telenor Arena 2017” taken by Flickr User Kim Erlandsen, NRK P3 (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

—

Todd Craig (he/him) is a writer, educator and DJ whose career meshes his love of writing, teaching and music. His research inhabits the intersection of writing and rhetoric, sound studies and Hip Hop studies. He is the author of “K for the Way”: DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies (Utah State University Press) which examines the Hip Hop DJ as twenty-first century new media reader, writer, and creator of the discursive elements of DJ rhetoric and literacy. Craig’s publications include the multimodal novel tor’cha (pronounced “torture”), and essays in various edited collections and scholarly journals including The Bloomsbury Handbook of Hip Hop Pedagogy, Amplifying Soundwriting, Methods and Methodologies for Research in Digital Writing and Rhetoric, Fiction International, Radical Teacher, Modern Language Studies, Changing English, Kairos, Composition Studies and Sounding Out! Dr. Craig teaches courses on writing, rhetoric, African American and Hip Hop Studies, and is the co-host of the podcast Stuck off the Realness with multi-platinum recording artist Havoc of Mobb Deep. Presently, Craig is an Associate Professor of African American Studies at New York City College of Technology and English at the CUNY Graduate Center.

LeBrandon Smith (he/him) is a cultural curator and social impact leader born and raised in Brooklyn and Queens, respectively. Coming from New York City, his efforts to bridge gaps, and build community have been central to his work, but most notably his passion for music has fueled his career. His programming has been seen throughout the Metropolitan area, including historical venues like Carnegie Hall, The Museum of the City of NY (MCNY) and Brooklyn Public Library.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“Heavy Airplay, All Day with No Chorus”: Classroom Sonic Consciousness in the Playlist Project—Todd Craig

SO! Reads: “K for the Way”: DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies—DeVaughn (Dev) Harris

Caterpillars and Concrete Roses in a Mad City: Kendrick Lamar’s “Mortal Man” Interview with Tupac Shakur–Regina Bradley

Caterpillars and Concrete Roses in a Mad City: Kendrick Lamar’s “Mortal Man” Interview with Tupac Shakur

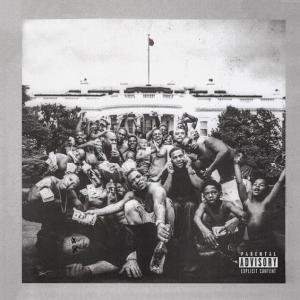

I’ve been hesitant to write about Kendrick Lamar’s 2015 album To Pimp a Butterfly (TPAB) because there are layers to the shit. Sonic, cultural, and political layers that need time to breathe and manifest. Some of those layers are pedagogical. For example, Brian Mooney brilliantly paired the album with Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye to help students work through themes of Black consciousness and self-love. Mooney’s lesson plan garnered Lamar’s attention and a recent visit with Mooney students. Lamar’s open grappling with art and blackness throw him into heavy debates about his worth as a cultural and even literary icon. Yet Lamar’s formula of introspective angst – the use of battling his own demons to shed light on broader American society – pulls me to think about how Lamar and TPAB fit into a long standing trajectory of Black folks’ self-examination in art as a frame for larger critiques of racial politics in American society.

I’m drawn to TPAB’s outro of the final track of the album “Mortal Man.” “Mortal Man” sonically invokes Lamar’s struggle to assume a position as a gatekeeper of a branch of hip hop that focuses on Black community and self-actualization. The track includes a sample from a 1994 Tupac Shakur interview with Swedish music journalist Mats Nileskär. Lamar positions himself as the interviewer, asking a different set of questions that engages Shakur about walking the fault lines of fame, fortune, and Black consciousness in this current cycle of hip hop. The construction and execution of the interview revisits the lines between hip hop’s collective and generational responsibilities via Lamar and Shakur’s interaction. Their conversation moves from creative (and creating) political protest to larger philosophical questions within hip hop: self-consciousness, mortality, and death. Lamar parallels his angst with Tupac using his voice, with Tupac himself heralded as hip hop’s martyred t.h.u.g. with a conscience. In this contemporary moment where Black men’s mortality and worth is attached to being a thug and a problem, Lamar poses Shakur in “Mortal Man” as a keystone for connecting popular scripts with cultural expectations of Black masculinity and agency in the United States.

The song “Mortal Man” launches the interview. The track can be considered a double sample – it uses Houston Person’s cover of Fela Kuti’s song “I No Get Eye for Back.” Lamar’s voice is clear but the background track soft and subdued, forcing the listener to pay full attention to Lamar’s voice, which interrogates what it takes for one to be loyal or respected in mainstream America. Percussion (bass kicks, acoustic drums, soft piano chords) and bass guitar chords annotate Lamar’s solemn lyrical delivery. A horn and woodwind medley – lead by Houston’s tenor sax playing – punctuate Lamar’s chorus:

When the shit hit the fan, is you still a fan?

When the shit his the fan, is you still a fan?

Want you to look to your left and right, make sure you ask your friends

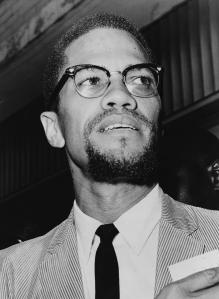

The instrumental accompaniment is soft and steady, suggesting Lamar’s question is a continuous negotiation or checklist for one’s proclamation of loyalty and respect. Lamar’s repetition of “when the shit hit the fan is you still a fan” addresses his fanbase and the followers of other notable Black cultural and creative leaders. They, like Lamar, are usefully flawed – whether by accusation or self-proclamation – and use their flaws to further their cause. Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Moses, Malcolm X, and Michael Jackson all exhibited social-cultural and political agency for (Black) folks. Yet they also suffered scrutiny and disregard because of their personal lives or less-than-respectable experiences.

Malcolm X at Queens Court. Source=Library of Congress. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c11166 Author=Herman Hiller, World Telegram staff photographer

I am especially intrigued by Lamar’s reference to Malcolm X as “Detroit Red,” a nickname X had as a young hellraiser before his conversion to Islam. Lamar’s reference to X in his youth here speaks to larger questions of respectability, Black youth, and protest. Detroit Red is young, flawed but influential, similar to Lamar and other young Black folks leading protests in this contemporary moment. Lamar’s roll call suggests a struggle with the question of authority, both as a creator of Black culture and how his music implies a larger struggle of contemporary Black agency and angst. Interviewing Tupac brings Lamar’s struggle to a head, evoking Shakur’s voice as a culturally recognizable authority of hip hop’s commercial progress and cultural process. The trope of a flawed nature as a departure point for creative expression and agency is a theme that runs throughout TPAB and the rest of Lamar’s musical catalogue.

The musical accompaniment to the “Mortal Man” song fades out and against a backdrop of silence Lamar begins to recite what he states is an unfinished piece. He begins, “I remember when you was conflicted,” which implies he is talking to himself or talking to someone else. The background silence that leads to Lamar and Shakur’s conversation is as telling as the conversation itself, sonically alluding both to Lamar’s ‘quiet’ struggles of self-affirmation and the possibility that someone other than the audience is listening. The quiet is Lamar’s moment of clarity; the listeners are with him at his most vulnerable moment. He uses the silence to focus attention on himself and without the ‘outside noise’ of others’ beliefs and impressions of his music and purpose.

Although the interview takes place over 20 years earlier, Tupac’s answers are clear and ‘live.’ Shakur’s initial voice is pensive and calculating – he sounds like he is thinking through his responses as he speaks – but later sounds more relaxed, laughing and talking louder and faster. The decreasing formality of Shakur’s answers suggests his increasing comfort with the interviewer as well as confidence in his own answers (and ultimately in sharing his beliefs). Lamar’s use of Shakur’s voice serves as the ultimate form of crate digging, using an obscure (or rare) radio interview sample to create his own voice in hip hop. Lamar’s engagement with Shakur serves memory as a cultural archive and as a cultural production. He not only preserves Shakur’s legacy in his own words but uses Shakur as a departure point for how to blur acts of listening for hip hop fans in a digital age.

The act of listening takes center stage for the interview. The interview is presented as an informal sitdown, reminiscent of what takes place during studio sessions: artists share new material and garner advice from veteran artists. Both rookies and veteran artist listen for new perspectives and listening for suggestions to approach a topic or track. Listening here shows Lamar’s awe and respect of Shakur’s perspective and artistry but also hints at how his conversation with Shakur is ultimately a conversation with himself. Lamar starts the conversation with an unfinished piece about his angsts regarding commercial success and how it conflicts with his creative process. He then moves on to asking Shakur about how he grapples with his creative and political consciousness. The listening work taking place here is critical and archival: without Lamar’s (and Lamar’s audience) interest in Shakur’s creative process his voice loses authority and ultimately its power.

Tupac’s sonic ‘resurrection’ signifies his lasting effect in hip hop while serving as a springboard for Lamar’s own pondering about the purpose of his music and the burden of its success. Unlike the visual representation of Shakur via hologram at the 2012 Coachella Music Festival, Lamar’s use of Tupac’s sonic likeness offers an alternative entry point for engaging Tupac’s work outside of his rapping. For example, much of Shakur’s social-political work takes place in his poetry i.e. his collection of poetry The Rose that Grew from Concrete. Further, the ‘thingness’ of the hologram, a physical and technological manifestation of hip hop fans’ and artists’ revering of Tupac’s image and death, makes me think about the type of work the hologram was expected to perform as compared to the sonic ‘ghostliness’ of Tupac’s voice on Lamar’s track. If, as John Jennings suggests, the hologram manifested Tupac as a “ghost in the machine,” how does Tupac’s voice work as a ghost in the machine? On a visceral level hearing Tupac’s voice in conversation with Kendrick Lamar stirs feelings about whether or not he is dead or alive and his immortality as a hip hop icon.

Where the Coachella hologram visualized Tupac Shakur spirit, “Mortal Man” sonically evokes his spirit and the connection between his (im)mortality and storytelling. Lamar says: “Sometimes I be like. . .get behind a mic and I don’t what type of energy I’ma push out or where it comes from.” Shakur responds “because the spirits, we ain’t really even rappin’, we just letting our dead homies tell stories for us.” Listening to Shakur’s use of “we” out of historical context – the interview took place in 1994, 21 years before “Mortal Man” – suggests that Tupac himself is among the dead. He is a “dead homie” and telling a story that Lamar himself is trying to relay to his audience and himself. Yet the lingering possibility of Tupac’s mortality – most embodied in Tupac’s silence after Lamar’s discussion of the significance of a caterpillar to the album – is a powerful moment of protest. Shakur’s quiet and Lamar’s attempt to “call him back,” signifies a period in the conversation. Lamar is left to fend for himself, fighting a “fight he can’t win.” There is also the possibility that his exchange with Shakur is “just some shit he wrote,” an unfinished idea and story that he is still figuring out. Lamar’s rendering of Tupac’s voice makes me think about the DJ Spooky statement “the voice you speak with may not be your own.” Tupac’s ghostly voice and Lamar’s search for his own voice blend to present Tupac as a mouthpiece for not only himself but Lamar.

At surface level Lamar resurrects and interviews Tupac Shakur because of regional ties to West Coast hip hop and a nearly standard declaration in rap of Shakur’s influence and fandom. He is arguably the most celebrated and iconic figure in hip hop. Shakur’s untimely death and open struggles with seeking balance between fame and personal responsibility mold him as hip hop’s shining prince. Shakur’s family ties with the Black Panther Party – a member of the Panthers once called him an “eternal cub” – positioned him to use hip hop as a mouthpiece for contemporary Black protest. But Shakur’s branding of protest and hip hop was messy, in part because of a working understanding and maneuvering of his image as controversial and commercially successful.

The “Mortal Man” interview signifies sound’s ability to usefully bridge past and present social, cultural, and political moments. Lamar’s sonic evoking of Tupac Shakur demonstrates hip hop as a space of Black youth political protest. Lamar uses sound to render hip hop temporality and re-emphasize Black popular culture as a departure point for recognizing contemporary Black angst. The shrinking mediums of spaces available to indicate why and how #BlackLivesMatter position the sonic as a work bench for engaging race relations in a deemed post-racial era. The “Mortal Man” interview serves as a blueprint for connecting hip hop to longstanding conversations about Black protest as a (messy) cultural product.

—

Featured image: “Shot by Drew: Kendrick Lamar” by Flickr user The Come Up Show, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

—

Regina Bradley recently completed her PhD at Florida State University in African American Literature. Her dissertation is titled “Race to Post: White Hegemonic Capitalism and Black Empowerment in 21st Century Black Popular Culture and Literature.” She is a regular writer for Sounding Out!

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

I Been On: BaddieBey and Beyoncé’s Sonic Masculinity — Regina Bradley

Saving Sound, Sounding Black, Voicing America: John Lomax and the Creation of the “American Voice”— Toniesha Taylor

Como Now? Marketing “Authentic” Black Music— Jennifer Stoever

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- SO! Reads: Alexis McGee’s From Blues To Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics

- SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

- Impaulsive: Bro-casting Trump, Part I

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments