Youth, Reverberations, and Detroit’s Most Charismatic Rapper

“Type in Sada Baby on the computer and let them hear the difference.”

Devante gives me this advice in the midst of an escalating back-and-forth among his peers about the difference between singing and rapping. Eighteen middle schoolers lounge around two picnic tables inside our local community center for this six-week summer program. We’re still in the first week, and each day they’ve name-checked Sada Baby, a charismatic rapper from the eastside of Detroit. I’m too occupied at the moment—trying to keep the conversation from spilling into an argument—to heed Devante’s advice, so he takes matters into his own voice.

“Rapping is like this,” he tells the group while starting to nod his head to an ear-magined beat. “Oh boy, I ain’t playing no games!” Devante raps the first half-bar of “Oh Boy,” Sada Baby’s 2017 track that narrates his street exploits and threatens his rivals — often with violence to the women they might or might not love. Devante not only raps this opening line but approximates the grain of Sada Baby’s voice, at least as much as he can since his adolescent tone hasn’t yet caught up to his linebacker build. My own ear—from over 20 years as hip-hop DJ, turntablist, and vinyl enthusiast—is more Sadat X than Sada Baby. But Sada’s playful allure is audible even to me, like while bending his cadence into indecipherable sounds over the track’s intro. And he covered “Return of the Mack” into a shirtless gunplay revenge track. So there’s that, too. I can understand the affective draw he has on the young people in the room. And even if couldn’t, this wouldn’t be the last I would hear of him in Yaktown Sounds that summer.

Yaktown Sounds is an emergent space of sound making I curate in and around Pontiac, Michigan. (Pon-ti-Yak = Yaktown, get it?) A postindustrial city halfway between Detroit and Flint, Pontiac is the home of jazz drummer Elvin Jones, hip-hop group Binary Star, and perhaps the most respected battle rapper on the national scene today: JC. Since 2015, I’ve organized an evolving network of artists—usually DJs and beat makers—to make space for youth and community members to play with sound. Of course, play and sound go well together. In Yaktown Sounds, sometimes it’s elementary-age youth at the public library hitting pads and twisting knobs on MIDI controllers until they like what they hear. Other times it’s daddies and daughters scratching a record under the needle to see what comes out. The summer of 2017, I lined up a different musical artist each week from Pontiac and Detroit to visit and share their skills.

My curatory approach to this space takes inspiration from Saving Our Lives Hear Our Truths (SOLHOT), a creative, visionary, performative Black girlhood practice. In part, SOLHOT generates from a particular stance on Black girlhood sound. In Hear Our Truths (2013), SOLHOT visionary Ruth Nicole Brown theorizes Black girlhood sound and the ways it resists and improvises around neoliberal youth programming constraints that are intended to “fix” youth. Riffing off Tricia Rose in Black Noise, Brown theorizes Black girlhood as a sound nobody can organize. It bounces off adult listenings that would compress it into binary identity positions like sass/silence or into white mainstream notions of politeness and civility. What follows from this stance are not constrained, prescribed “learning environments” for youth but open, performative, imaginative spaces not always under adults’ control. This is the type of environment I try to facilitate in Yaktown Sounds.

This stance toward space and environment means vulnerability to reverberations and their affects. Reverberation, of course, is a phenomenon and technique that plays a prominent role in Black diasporic sonic expression. As Michael E. Veal writes, its affect/effect is most pronounced through Jamaican dub music: the collisions among sounds through echo, delay, and reverb. Veal’s engagement with dub and reverberation is also conceptual. In Dub (2013), he considers its echoes and ruptures “a sonic metaphor for the condition of diaspora” (197). In Sound Curriculum (2018), Walter Gershon thinks with sound to make a similar argument for reverberation and other physical, metaphysical, and aural phenomena: “Because sounds are already in motion, they are always reverberating, bouncing off of objects from sinus cavities to walls to coral to brush to air to water to stone” (56). In these instances, Veal and Gershon take up reverberation in both aural and environmental settings. Yet these ideas also apply to the spaces where youth and adults co-create together. What collides, bounces, and stays in motion? What counts as a reverberation?

In that summer of Yaktown Sounds, I understand Sada Baby’s aural presence as a kind of reverberation. He stayed in motion, colliding with youth judgments about what counted as rap, how a rapper’s voice should sound, and even my own aspirations for the space. These collisions were most apparent while preparing each week for our visiting artist.

Before a visit from Mahogany Jones, we watched the video for her song “Blue Collar Logic.” Landon was the first to respond while leaning back against the table, feet kicked out in front of him, and retwisting his short bronze locks:

“Can we see another one? That one wasn’t good. I didn’t think it was good. Not as good as I thought it would be. It was too much of that, uh, old time. I just think she didn’t rap enough.”

For Landon, the standard for rapping enough and not sounding “old time” was—you guessed it—Sada Baby. “He actually raps,” Landon noted while explaining. If we consider music and song not only as art but as different organizations of sound (another point from Gershon), Landon has a point. To get specific, some of Sada Baby’s songs are continuous bars of rapping — no hooks, no chorus, no rest. In “Oh Boy,” Sada Baby raps for two minutes and 20 seconds of the song, and guest artist FMB DZ raps a 40 second verse. Straight bars over a trap beat. By comparison, “Blue Collar Logic” is also roughly 3-minutes long but has a fuller song structure. Mahogany Jones raps for 1 minute and 20 seconds across two verses. In the golden era template of DJ Premier, cuts from DJ Los make up the 30-second intro, the two choruses, and the instrumental outro that lasts approximately one minute. If we do the math, Sada Baby’s track has more than double the rapping compared to Mahogany’s.

My point here isn’t to judge which organization of sound is better; there is no wrong way to organize sound. Rather, these details illustrate two very different organizations and how Sada Baby’s made up the basis for Landon’s judgment.

If Landon’s directness that “she didn’t rap enough” rings a bit harsh to our polite adult listenings, then hear Kareem slice through the group conversation after listening to hometown artist Kodac aka M80, who had just returned from a European tour:

“He don’t know how to rap.”

Kareem’s judgment was based upon what he heard as singing and rapping happening in the same song, an organization of sound he classified as “old.” When I asked Kareem what Kodac needed to do to be a better rapper — “in your opinion,” the recommendation was equally direct: “Be more like Sada Baby.”

These responses from Landon and Kareem show us something else about the movement of reverberations through this space. Sada Baby’s aural presence not only collided with youth preferences and claims about rap. As a reverberation, he was used to berate other artists whose sounds and configurations of sound were heard as “old” through youths’ generationally tuned ears.

Despite the youth-centric stance I take on spaces like Yaktown Sounds, I’m not gonna lie: the strikes and blows of these reverberations hit me too because of the relational ties I hold with these artists. They are part of my own creative community. I’ve DJed on stage for Kodac. I go to all of Mahogany’s shows. As a result, I remain vulnerable to the force of these reverberations. Owning up to that point, I am reminded of what Shakira Holt teaches us about adults and how we listen, particularly in education settings: sometimes we are not as open-eared to youth as we imagine ourselves to be — especially given the ways we have been socialized to censor and silence Black youth, even ones who live through our own cities, schools, and community centers. Though I’m two years removed from this particular iteration of Yaktown Sounds, Sada Baby continues to reverberate with/against me. He stays in motion even now, echoing through my writing as I toggle over to his Soundcloud page, press play on his songs, and wonder if I will hear something that makes me tune in differently to the young people around me.

—

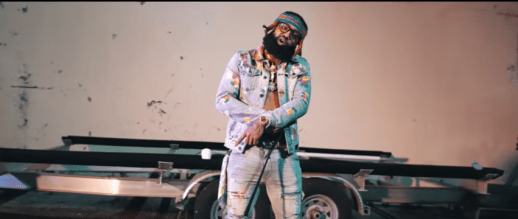

Featured image: Screenshot from “Sada Baby–On Gang”

—

Emery Marc Petchauer makes beats and DJs with kids in and around Pontiac, MI. A former high school English teacher, he works as an associate professor of English and Teacher Education at Michigan State University. His scholarship has addressed the aesthetic practices of hip-hop culture and their connections to teaching, learning, and living. He also studies the high stakes test educators must pass to become certified teachers. He is online at empetch.com and on Twitter at @emerypetchauer.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Deep Listening as Philogynoir: Playlists, Black Girl Idiom, and Love–Shakira Holt

The Sounds of Anti-Anti-Essentialism: Listening to Black Consciousness in the Classroom–Carter Mathes

Can’t Nobody Tell Me Nothin: Respectability and The Produced Voice in Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road”–Justin Burton

SO! Reads: Steph Ceraso’s Sounding Composition: Multimodal Pedagogies for Embodied Listening

Pedagogy at the convergence of sound studies and rhetoric/composition seems to exist in a quantum state—both everywhere and nowhere at the same time. This realization simultaneously enlightens and frustrates. The first page of Google results for “sound studies” and “writing instruction” turns up tons of pedagogy; almost all of it is aimed at instructors, pedagogues, and theorists, or contextualized in the form of specific syllabi. The same is true for similar searches—such as “sound studies” + “rhetoric and composition”—but one thing that remains constant is that Steph Ceraso, and her new book Sounding Composition (University of Pittsburgh Press: 2018) are always the first responses. This is because Ceraso’s book is largely the first to look directly into the deep territorial expanses of both sound studies and rhet/comp, which in themselves are more of a set of lenses for ever-expanding knowledges than deeply codified practices, and she dares to bring them together, rather than just talking about it. This alone is an act of academic bravery, and it works well.

Pedagogy at the convergence of sound studies and rhetoric/composition seems to exist in a quantum state—both everywhere and nowhere at the same time. This realization simultaneously enlightens and frustrates. The first page of Google results for “sound studies” and “writing instruction” turns up tons of pedagogy; almost all of it is aimed at instructors, pedagogues, and theorists, or contextualized in the form of specific syllabi. The same is true for similar searches—such as “sound studies” + “rhetoric and composition”—but one thing that remains constant is that Steph Ceraso, and her new book Sounding Composition (University of Pittsburgh Press: 2018) are always the first responses. This is because Ceraso’s book is largely the first to look directly into the deep territorial expanses of both sound studies and rhet/comp, which in themselves are more of a set of lenses for ever-expanding knowledges than deeply codified practices, and she dares to bring them together, rather than just talking about it. This alone is an act of academic bravery, and it works well.

Ceraso established her name early in the academic discourse surrounding digital and multimodal literacy and composition, and her work has been nothing short of groundbreaking. Because of her scholarly endeavors and her absolute passion for the subject, it is no surprise that some of us have waited for her first book with anticipation. Sounding Composition is a multivalent, ambitious work informs the discipline on many fronts. It is an act of ongoing scholarship that summarizes the state of the fields of digital composition and sonic rhetorics, as well as a pedagogical guide for teachers and students alike.

Through rigorous scholarship and carefully considered writing, Ceraso manages to take many of the often-nervewracking buzzwords in the fields of digital composition and sonic rhetorics and breathe poetic life into them. Ceraso engages in the scholarship of her field by demystifying the its jargon, making accessible to a wide variety of audiences the scholar-specific language and concepts she sets forth and expands from previous scholarship (though it does occasionally feel trapped in the traditional alphabetic prison of academic communication).. Her passion as an educator and scholar infuses her work, and Ceraso’s ontology re-centers all experience–and thus the rhetoric and praxis of communicating that experience–back into the whole body. Furthermore, Ceraso’s writing makes the artificial distinctions between theory and practice dissolve into a mode of thought that is simultaneously conscious and affective, a difficult feat given her genre and medium of publication. Academic writing, especially in the form of a university press book, demands a sense of linearity and fixity that lacks the affordances of some digital formats in terms of envisioning a more organic flow between ideas. However, while the structure of her book broadly follows a standard academic structure, within that structure lies a carefully considered and deftly-organized substructure.

Through rigorous scholarship and carefully considered writing, Ceraso manages to take many of the often-nervewracking buzzwords in the fields of digital composition and sonic rhetorics and breathe poetic life into them. Ceraso engages in the scholarship of her field by demystifying the its jargon, making accessible to a wide variety of audiences the scholar-specific language and concepts she sets forth and expands from previous scholarship (though it does occasionally feel trapped in the traditional alphabetic prison of academic communication).. Her passion as an educator and scholar infuses her work, and Ceraso’s ontology re-centers all experience–and thus the rhetoric and praxis of communicating that experience–back into the whole body. Furthermore, Ceraso’s writing makes the artificial distinctions between theory and practice dissolve into a mode of thought that is simultaneously conscious and affective, a difficult feat given her genre and medium of publication. Academic writing, especially in the form of a university press book, demands a sense of linearity and fixity that lacks the affordances of some digital formats in terms of envisioning a more organic flow between ideas. However, while the structure of her book broadly follows a standard academic structure, within that structure lies a carefully considered and deftly-organized substructure.

Sounding Composition begins with a theory-based introduction in which Ceraso lays the book’s framework in terms of theory and structure. Then proceeds the chapter on the affective relationship between sound and the whole body. The next chapter investigates the relation of sonic environments and the body, followed by a chapter on our affective relationship with consumer products, in particular the automobile, perhaps the most American of factory-engineered soundscapes. Nested in these chapters is a rhetorical structure that portrays a sense of movement, but rather than moving from the personal out into spatial and consumer rhetorics, Sounding Composition’s chapter structure moves from an illustrative example that clearly explains the point Ceraso makes, into the theories she espouses, into a “reverberation” or a pedagogical discussion of an assignment that helps students better grasp and respond to the concepts providing the basis for her theory. This practice affords Ceraso meditation on her own practices as well as her students’ responses to them, perfectly demonstrating the metacognitive reflection that so thoroughly informs rhet/comp theory and praxis.

Chapter one, “Sounding Bodies, Sounding Experience: (Re)Educating the Senses,” decenters the ears as the sole site of bodily interaction with sound. Ceraso focuses on Dame Evelyn Glennie, a deaf percussionist, who Ceraso claims can “provide a valuable model for understanding listening as a multimodal event” (29) because these practices expand listening to faculties that many, especially the auditorially able, often ignore. Dame Glennie theorizes, and lives, sound from the tactile ways its vibrations work on the whole body. From the new, more comprehensive understanding of sound Dame Glennie’s deafness affords, we can then do the work of “unlearning” our ableist auditory and listening practices, allowing all a more thorough reckoning with the way sound enables us to understand our environments.

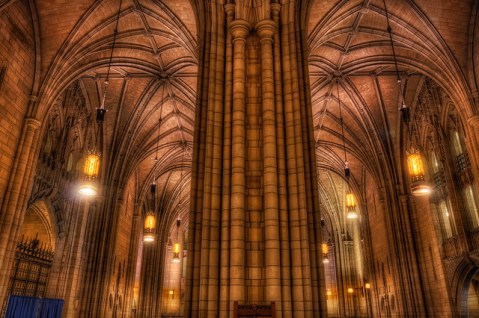

The ability to transmit, disrupt, and alter the vibrational aspects of sound are key to understanding how we interact with sound in the world, the focus of the second chapter in Sounding Composition. In “Sounding Space, Composing Experience: The Ecological Practice of Sound Composition,” Ceraso situates her discussion in the interior of the building where she actually composed the chapter. The Common Room in the Cathedral of Learning, on the University of Pittsburgh’s main campus, is vast, ornate, and possessed of a sense of quiet which “seems odd for a bustling university space”(69). As Ceraso discovered, the room itself was designed to be both vast and quiet, as the goal was to produce a space that both aesthetically and physically represented the solemnity of education.

Cathedral of Learning Ceiling and Columns, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Image by Flickr User Matthew Paulson (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

To ensure a taciturn sense of stillness, the building was constructed with acoustic tiles disguised as stones. These tiles serve to not only hearken back to solemn architecture but also to absorb sound and lend a reverent air of stillness, despite the commotion. The deeply intertwined ways in which we interact with sound in our environment is crucial to further developing Ceraso’s affective sonic philosophy. This lens enables Ceraso to draw together the multisensory ways sound is part of an ecology of the material aspects of the environment with the affective ways we interact with these characteristics. Ceraso focuses on the practices of acoustic designers to illustrate that sound can be manipulated and revised, that sound itself is a composition, a key to the pedagogy she later develops.

Framing the discussion of sound as designable—a media manipulated for a desired impact and to a desired audience–serves well in introducing the fourth chapter, which examines products designed to enhance consumer experience. “Sounding Cars, Selling Experience: Sound Design in Consumer Products,” moves on to discuss the in-car experience as a technologically designed site of multisensory listening. Ceraso chose the automobile as the subject of this chapter because of the expansive popularity of the automobile, but also because the ecology of sound inside the car is the product of intensive engineering that is then open to further manipulation by the consumer. Whereas environmental sonic ecologies can be designed for a desired effect, car audio is subject to a range of intentional manipulations on the listener. Investigating and theorizing the consumer realm not only opens the possibilities for further theorization, but also enhances the possibility that we might be more informed in our consumer interactions. Understanding the material aspects of multimodal sound also further informs and shapes disciplinary knowledge at the academic level, framing the rhetorical aspect of sonic design as product design so that it focuses on, and caters to, particular audiences for desired effects.

Heading Up the Mountain, Image by Flickr User Macfarland Maclean,(CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Sounding Composition is a useful and important book because it describes a new rhetoric and because of how it frames all sound as part of an affective ontology. Ceraso is not the first to envision this ontology, but she is the first to provide carefully considered composition pedagogy that addresses what this ontology looks like in the classroom, which are expressed in the sections in Sounding Composition marked as “Reverberations.” To underscore the body as the site of lived experience following chapter two, Ceraso’s “reverberation” ask students to think of an experience in which sound had a noticeable effect on their bodies and to design a multimodal composition that translates this experience to an audience of varying abledness. Along with the assignment, students must write an artist statement describing the project, reflecting on the composition process, and explaining each composer’s choices.

To encourage students to think of sound and space and the affective relationship between the two following chapter three, Ceraso developed a digital soundmap on soundcities.com and had students upload sounds to it, while also producing an artist statement similar to the assignment in the preceding chapter. Finally, in considering the consumer-ready object in composition after the automobile chapter, students worked in groups to play with and analyze a sound object, and to report back on the object’s influence on them physically and emotionally. After they performed this analysis, students are then tasked with thinking of a particular audience and creating a new sonic object or making an existing sonic object better, and to prototype the product and present it to the class. Ceraso follows each of these assignment descriptions with careful metacognitive reflection and revision.

Steph Ceraso interviewed by Eric Detweiler in April 2016, host of Rhetoricity podcast. They talked sound, pedagogy, accessibility, food, senses, design, space, earbuds, and more. You can also read a transcript of this episode.

While Sounding Composition contributes to scholarship on many levels, it’s praxis feels the most compelling to me. Ceraso’s love for the theory and pedagogy is clear–and contagious—but when she describes the growth and evolution of her assignments in practice, we are able to see the care that she has for students and their individual growth via sound rhetoric. To Ceraso, the sonic realm is not easily separated from any of the other sensory realms, and it is an overlooked though vitally important part of the way we experience, navigate, and make sense of the world. Ceraso’s aim to decenter the primacy of alphabetic text in creating, presenting, and formulating knowledge might initially appear somewhat contradictory, but the old guard will not die without a fight. It could be argued that this work and the knowledge it uncovers might be better represented outside of an academic text, but that might actually be the point. Multimodal composition is not the rule of the day and though the digital is our current realm, text is still the lingua franca. Though it may seem like it will never arrive, Ceraso is preparing us for the many different attunements the future will require.

—

Featured Image: Dame Evelyn Glennie Performing in London in 2011, image by Flickr User PowderPhotography (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

—

Airek Beauchampis an Assistant Professor of English at Arkansas State University and Editor-at Large for Sounding Out! His research interests include sound and the AIDS crisis, as well as swift and brutal punishment for any of the ghouls responsible for the escalation of the crisis in favor of political or financial profit. He fell in love in Arkansas, which he feels lends undue credence to a certain Rhianna song.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Queer Timbres, Queered Elegy: Diamanda Galás’s The Plague Mass and the First Wave of the AIDS Crisis– Airek Beauchamp

Botanical Rhythms: A Field Guide to Plant Music -Carlo Patrão

Sounding Our Utopia: An Interview With Mileece–Maile Colbert

Recent Comments