A Conversation With Themselves: On Clayton Cubitt’s Hysterical Literature

Welcome to our second installment of Hysterical Sound. Last week I discussed silence and hysteria in relation to Sam Taylor-Johnson’s silent film Hysteria, suggesting that the hysteric’s vocalizations go unheard because we have tuned them out. In upcoming weeks Veronica Fitzpatrick will explore how the soundtrack of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre can be considered hysterical in its rejection of language and meaning and John Corbett, Terri Kapsalis and Danny Thompson share an excerpt from their performance of The Hysterical Alphabet.

Welcome to our second installment of Hysterical Sound. Last week I discussed silence and hysteria in relation to Sam Taylor-Johnson’s silent film Hysteria, suggesting that the hysteric’s vocalizations go unheard because we have tuned them out. In upcoming weeks Veronica Fitzpatrick will explore how the soundtrack of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre can be considered hysterical in its rejection of language and meaning and John Corbett, Terri Kapsalis and Danny Thompson share an excerpt from their performance of The Hysterical Alphabet.

Today, Gordon Sullivan, considers the video art series Hysterical Literature in relation to a long history of women’s vocalizations serving as aural fetishes for the pleasure of male listeners. In doing so he troubles the dichotomies raised by the project, dichotomies between masculine visual pleasure and feminine aurality, between language and bliss.

— Guest Editor Karly-Lynne Scott

—

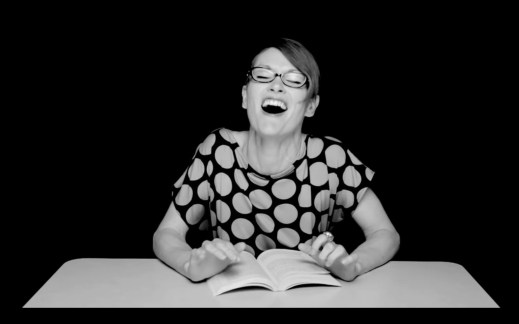

Each video in filmmaker and photographer Clayton Cubitt’s Hysterical Literature series (2012-) – which consists of 11 “sessions” so far – appears deceptively simple. We see a black and white frame with a clothed woman seated at a table, visible from the sternum up, holding a book of her choosing. She announces her name and the title of the book before beginning to read. While reading, the subject generally begins to stumble, the speeding of reading slowing down or speeding up, changes in pitch and emphasis growing more pronounced. Eventually, she is able to read no more and gives in to sighs, groans, or silent, eye-closing paroxysms. When she returns to herself, she announces again her name and the title of the book before the “session” ends.

Despite the consistency of the concept, the 11 “sessions” have been viewed a combined 45 million times, and perhaps much of the appeal of the series is in what it doesn’t show. What we do not see – and indeed do not hear – is the “assistant” beneath the table with an Hitachi Magic Wand physically stimulating the subject. What might have been errors or difficulties in the reading are retroactively understood as evidence of the difficulty of “performing” under the attention of the vibrator.

According to Cubitt, the series’ title and conceit nod at the Victorian-era propensity for naming “unruly” female behavior as “hysterical,” where the cure was often the application of a vibrating device to produce “release.” Female sexuality is therefore the absent center of Hysterical Literature – it is there, but can be disavowed (at least visually), a trend that places it firmly in a culture that has an ambiguous relationship to female pleasure and its sounds.

As John Corbett and Terri Kapsalis note in “Aural Pleasure: The Female Orgasm in Popular Sound,” the sounds of female pleasure are “more viable, less prohibited, and therefore more publically available form of representation than, for instance, the less ambiguous, more easily recognized money shot” that characterizes “hard core” pornography (104). Certainly Hysterical Literature’s home on YouTube would seem to confirm Corbett and Kapsalis’ claim that sounds of female pleasure “occur in places…that would otherwise ban visual pornography” (104).

Indeed, the question of pornography looms over Hysterical Literature, as Cubitt seeks to push on YouTube’s “Community Guidelines” by exhibiting female pleasure sonically (See also Joshua Hudelson for a discussion of sexual fetish and the ASMR community on Youtube). Here the sound of the subject’s voice echoes Linda Williams’s description in Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and “The Frenzy of the Visible,” where the female voice “may stand as the most prominent signifier of female pleasure” that can stand in for the pleasure we are denied access to visually (123). In this way, the sound of female pleasure is, as Corbett and Kapsalis suggest, always evidentiary (104). For them, a woman’s pleasure may/must be corroborated by her sounds (For an alternative view of gender and sound as it relates to women, see Robin James’ “Gendered Voice and Social Harmony”).

This pleasure calls to mind Roland Barthes, who saw the possibility of bliss and representation as fundamentally incompatible. For Barthes, the “grain” of the voice is a bodily phenomenon, not one of language and signification. For him, “the cinema capture[s] the sound of speech close up…and make[s] us here in their materiality, their sensuality, the breath, the gutturals, the fleshiness of the lips, a whole presence of the human muzzle” (67). This “materiality” has a single purpose: bliss. This bliss doesn’t reside in language, with its representational aims, but in those aspects of the voice that are not ruled the signifier/signified dynamic.

What draws me to these discussions – and their relation to Hysterical Literature – is the almost overwhelming insistence on dichotomy. The visual “evidence” of hard core pornography is juxtaposed to the aural “evidence” of female pleasure. Male pleasure (on the side of the visible) is opposed to female pleasure (on the side of the invisible). Representation is incompatible with “bliss.”

This logic is not confined to discussions of sound, but is echoed in some of the writing on Hysterical Literature as well. In her profile (which included her own “session”), dancer and writer Toni Bentley argues that the series “juxtaposes the realm of words literally atop the realm of the erotic.” In her view, this immediately becomes a conflict: “Who would win the inevitable war? Upper body or lower? Logic or lust? Prefrontal cortex or hypothalamus?” Though her list of oppositions may seem idiosyncratic, she still insists on division before suggesting that what might emerge instead is that they “meld together.”

Bentley is not alone in understanding the videos this way, as other subjects find a clean break between “I am reading” and “I am orgasming” that would suggest a strict dichotomy between, as Barthes would put it, representation and bliss. For Bentley, this is a “literate, and literal, clitoral monologue that renders the Vagina Monologues merely aspirational.” I’m not sure that “monologue” captures the depth of what is happening in each Hysterical Literature session. Cubitt’s goal is to reveal something about his subjects, to use “distraction” as a means for revelation that ultimately removes him from the scene. Indeed, the participation of the vibrator-wielding “assistant” and Cubitt’s status as filmmaker argue that instead of a monologue, the series facilitates what Cubitt calls “a conversation with themselves.”

Though Cubitt and his subjects seek to maintain the division between the subject and her distraction, the series is far more interesting than that dichotomy would suggest. Hysterical Literature is interesting not because it juxtaposes “reading” and “orgasm,” but rather because of the rigor with which it is willing to dwell in between these two (apparently) opposed states. There is no cut, no switch in which a subject goes from reading to not-reading. Every video begins and ends the same way – we open on a woman telling us her name and her book, and end the same way, orgasm over with. In between, however, we have a combination of the book chosen by the subject and her augmented reading. Rather than the sighs and groans that supposedly evidence the subject’s pleasure, the more interesting elements are the sounds of the book transformed. The cadence that slows down, speeds up, gets lost, and must repeat. The drawn out vowels that teeter between a gracefully pronounced word and the abyss of unintelligibility. That the “struggle” will end in orgasms and the loss of speech is less significant than the attempt to maintain a voice in the face of what cannot be denied.

If we grant a gulf between “representation” and “bliss,” Hysterical Literature suggests that such a gulf is a productive place to be.

—

Gordon Sullivan is a PhD candidate at the University of Pittsburgh, currently writing a dissertation on questions of sensation and the political in exploitation films.

—

Featured image taken from “Hysterical Literature: Session Four: Stormy“.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Echo and the Chorus of Female Machines — AO Roberts

This Is How You Listen: Reading Critically Junot Díaz’s Audiobook — Liana M. Silva

Standing Up, For Jose — Mandie O’Connell

On Whiteness and Sound Studies

This is the first post in Sounding Out!’s 4th annual July forum on listening in observation of World Listening Day on July 18th, 2015. World Listening Day is a time to think about the impacts we have on our auditory environments and, in turn, their effects on us. For Sounding Out! World Listening Day necessitates discussions of the politics of listening and listening as a political act, beginning this year with Gustavus Stadler’s timely provocation. –Editor-in-Chief JS

This is the first post in Sounding Out!’s 4th annual July forum on listening in observation of World Listening Day on July 18th, 2015. World Listening Day is a time to think about the impacts we have on our auditory environments and, in turn, their effects on us. For Sounding Out! World Listening Day necessitates discussions of the politics of listening and listening as a political act, beginning this year with Gustavus Stadler’s timely provocation. –Editor-in-Chief JS

—

Many amusing incidents attend the exhibition of the Edison phonograph and graphophone, especially in the South, where a negro can be frightened to death almost by a ‘talking machine.’ Western Electrician May 11, 1889, (255).

What does an ever-nearer, ever-louder police siren sound like in an urban neighborhood, depending on the listener’s racial identity? Rescue or invasion? Impending succor or potential violence? These dichotomies are perhaps overly neat, divorced as they are from context. Nonetheless, contemplating them offers one charged example of how race shapes listening—and hence, some would say, sound itself—in American cities and all over the world. Indeed, in the past year, what Jennifer Stoever calls the “sonic color line” has become newly audible to many white Americans with the attention the #blacklivesmatter movement has drawn to police violence perpetrated routinely against people of color.

Racialized differences in listening have a history, of course. Consider the early decades of the phonograph, which coincided with the collapse of Reconstruction and the consolidation of Jim Crow laws (with the Supreme Court’s stamp of approval). At first, these historical phenomena might seem wholly discrete. But in fact, white supremacy provided the fuel for many early commercial phonographic recordings, including not only ethnic humor and “coon songs” but a form of “descriptive specialty”—the period name for spoken-word recordings about news events and slices of life—that reenacted the lynchings of black men. These lynching recordings, as I argued in “Never Heard Such a Thing,” an essay published in Social Text five years ago, appear to have been part of the same overall entertainment market as the ones lampooning foreign accents and “negro dialect”; that is, they were all meant to exhibit the wonders of the new sound reproduction to Americans on street corners, at country fairs, and in other public venues.

Thus, experiencing modernity as wondrous, by means of such world-rattling phenomena as the disembodiment of the voice, was an implicitly white experience. In early encounters with the phonograph, black listeners were frequently reminded that the marvels of modernity were not designed for them, and in certain cases were expressly designed to announce this exclusion, as the epigraph to this post makes brutally evident. For those who heard the lynching recordings, this new technology became another site at which they were reminded of the potential price of challenging the racist presumptions that underwrote this modernity. Of course, not all black (or white) listeners heard the same sounds or heard them the same way. But the overarching context coloring these early encounters with the mechanical reproduction of sound was that of deeply entrenched, aggressive, white supremacist racism.

The recent Sonic Shadows symposium at The New School offered me an opportunity to come back to “Never Heard Such a Thing” at a time when the field of sound studies has grown more prominent and coherent—arguably, more of an institutionally recognizable “field” than ever before. In the past three years, at least three major reference/textbook-style publications have appeared containing both “classic” essays and newer writing from the recent flowering of work on sound, all of them formidable and erudite, all of great benefit for those of us who teach classes about sound: The Oxford Handbook of Sound Studies (2012), edited by Karen Bijsterveld and Trevor Pinch; The Sound Studies Reader (2013), edited by Jonathan Sterne; and Keywords in Sound (2015), edited by David Novak and Matt Sakakeeny. From a variety of disciplinary perspectives, these collections bring new heft to the analysis of sound and sound culture.

I’m struck, however, by the relative absence of a certain strain of work in these volumes—an approach that is difficult to characterize but that is probably best approximated by the term “American Studies.” Over the past two decades, this field has emerged as an especially vibrant site for the sustained, nuanced exploration of forms of social difference, race in particular. Some of the most exciting sound-focused work that I know of arising from this general direction includes: Stoever’s trailblazing account of sound’s role in racial formation in the U.S.; Fred Moten’s enormously influential remix of radical black aesthetics, largely focused on music but including broader sonic phenomena like the scream of Frederick Douglass’s Aunt Hester; Bryan Wagner’s work on the role of racial violence in the “coon songs” written and recorded by George W. Johnson, widely considered the first black phonographic artist; Dolores Inés Casillas’s explication of Spanish-language radio’s tactical sonic coding at the Mexican border; Derek Vaillant’s work on racial formation and Chicago radio in the 1920s and 30s. I was surprised to see none of these authors included in any of the new reference works; indeed, with the exception of one reference in The Sound Studies Reader to Moten’s work (in an essay not concerned with race), none is cited. The new(ish) American Studies provided the bedrock of two sound-focused special issues of journals: American Quarterly’s “Sound Clash: Listening to American Studies,” edited by Kara Keeling and Josh Kun, and Social Text’s “The Politics of Recorded Sound,” edited by me. Many of the authors of the essays in these special issues hold expertise in the history and politics of difference, and scholarship on those issues drives their work on sound. None of them, other than Mara Mills, is among the contributors to the new reference works. Aside from Mills’s contributions and a couple of bibliographic nods in the introduction, these journal issues play no role in the analytical work collected in the volumes.

The three new collections address the relationship between sound, listening, and specific forms of social difference to varying degrees. All three of the books contain excerpts from Mara Mills’ excellent work on the centrality of deafness to the development of sound technology. The Sound Studies Reader, in particular, contains a small array of pieces that focus on disability, gender and race; in attending to race, specifically, Sterne shrewdly includes an excerpt from Franz Fanon’s A Dying Colonialism, as well as essays on black music by authors likely unfamiliar to many American readers. The Oxford Handbook’s sole piece addressing race is a contribution on racial authenticity in hip-hop. It’s a strong essay in itself. But appearing in this time and space of field-articulation, its strength is undermined by its isolation, and its distance from any deeper analysis of race’s role in sound than what seems to be, across all three volumes, at best, a liberal politics of representation or “inclusion.” Encountering the three books at once, I found it hard not to hear the implicit message that no sound-related topics other than black music have anything to do with race. At the same time, the mere inclusion of work on black music in these books, without any larger theory of race and sound or wider critical framing, risks reproducing the dubious politics of white Euro-Americans’ long historical fascination with black voices.

What I would like to hear more audibly in our field—what I want all of us to work to make more prominent and more possible—is scholarship that explicitly confronts, and broadcasts, the underlying whiteness of the field, and of the generic terms that provide so much currency in it: terms like “the listener,” “the body,” “the ear,” and so on. This work does exist. I believe it should be aggressively encouraged and pursued by the most influential figures in sound studies, regardless of their disciplinary background. Yes, work in these volumes is useful for this project; Novak and Sakakeeny seem to be making this point in their Keywords introduction when they write:

While many keyword entries productively reference sonic identities linked to socially constructed categories of gender, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, citizenship, and personhood, our project does not explicitly foreground those modalities of social difference. Rather, in curating a conceptual lexicon for a particular field, we have kept sound at the center of analysis, arriving at other points from the terminologies of sound, and not the reverse. (8)

I would agree there are important ways of exploring sound and listening that need to be sharpened in ways that extended discussion of race, gender, class, or sexuality will not help with. But this doesn’t mean that work that doesn’t consider such categories is somehow really about sound in a way that the work does take them up isn’t, any more than a white middle-class person who hears a police siren can really hear what it sounds like while a black person’s perception of the sound is inaccurate because burdened (read: biased) by the weight of history and politics.

In a recent Twitter conversation with me, the philosopher Robin James made the canny point that whiteness, masquerading as lack of bias, can operate to guarantee the coherence and legibility of a field in formation. James’s trenchant insight reminds me of cultural theorist Kandice Chuh’s recent work on “aboutness” in “It’s Not About Anything,” from Social Text (Winter 2014) and knowledge formation in the contemporary academy. Focus on what the object of analysis in a field is, on what work in a field is about, Chuh argues, is “often conducted as a way of avoiding engagement with ‘difference,’ and especially with racialized difference.”

I would like us to explore alternatives to the assumption that we have to figure out how to talk about sound before we can talk about how race is indelibly shaping how we think about sound; I want more avenues opened, by the most powerful voices in the field, for work acknowledging that our understanding of sound is always conducted, and has always been conducted, from within history, as lived through categories like race.

The cultivation of such openings also requires that we acknowledge the overwhelming whiteness of scholars in the field, especially outside of work on music. If you’re concerned by this situation, and have the opportunity to do editorial work, one way to work to change it is by making a broader range of work in the field more inviting to people who make the stakes of racial politics critical to their scholarship and careers. As I’ve noted, there are people out there doing such work; indeed, Sounding Out! has continually cultivated and hosted it, with far more editorial care and advisement than one generally encounters in blogs (at least in my experience), over the course of its five years. But if the field remains fixated on sound as a category that exists in itself, outside of its perception by specifically marked subjects and bodies within history, no such change is likely to occur. Perhaps we will simply resign ourselves to having two (or more) isolated tracks of sound studies, or perhaps some of us will have to reevaluate whether we’re able to teach what we think is important to teach while working under its rubric.

—

Thanks to Robin James, Julie Beth Napolin, Jennifer Stoever, and David Suisman for their ideas and feedback.

—

Gustavus Stadler teaches English and American Studies at Haverford College. He is the author of Troubling Minds: The Cultural Politics of Genius in the U. S.1840-1890 (U of Minn Press, 2006). His 2010 edited special issue of Social Text on “The Politics of Recorded Sound” was named a finalist for a prize in the category of “General History” by the Association of Recorded Sound Collections. He is the recipient of the 10th Annual Woody Guthrie fellowship! This fellowship will support research for his book-in-progress, Woody Guthrie and the Intimate Life of the Left.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Reading the Politics of Recorded Sound — Jennifer Stoever

Hearing the Tenor of the Vendler/Dove Conversation: Race, Listening, and the “Noise” of Texts — Christina Sharpe

Listening to the Border: “‘2487’: Giving Voice in Diaspora” and the Sound Art of Luz María Sánchez — Dolores Inés Casillas

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- SO! Reads: Alexis McGee’s From Blues To Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics

- SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

- Impaulsive: Bro-casting Trump, Part I

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments