Gendered Voices and Social Harmony

Editor’s Note: Our forum on gender and voice comes to a close today—and what a forum it has been! Last week AO Roberts talked about speech synthesis and why the robotic voices are so often female. That post followed Art Blake’s, where he talked about how his experience shifting his voice from feminine to masculine as a transgender man intersects with his work on John Cage. Before that, Regina Bradley put the soundtrack of Scandal in conversation with race and gender. The week before I talked about what it meant to have people call me, a woman of color, “loud.” The post that started it all? Christine Ehrick‘s selections from her forthcoming book, on the gendered soundscape.

Editor’s Note: Our forum on gender and voice comes to a close today—and what a forum it has been! Last week AO Roberts talked about speech synthesis and why the robotic voices are so often female. That post followed Art Blake’s, where he talked about how his experience shifting his voice from feminine to masculine as a transgender man intersects with his work on John Cage. Before that, Regina Bradley put the soundtrack of Scandal in conversation with race and gender. The week before I talked about what it meant to have people call me, a woman of color, “loud.” The post that started it all? Christine Ehrick‘s selections from her forthcoming book, on the gendered soundscape.

This week Robin James returns to SO! to round out our forum with an analysis of how ideas of what women should sound like have roots in Greek philosophy. So, lean in, close your eyes, and let the voices take you back in time. –Liana M. Silva, Managing Editor

—

Dove and Twitter’s #SpeakBeautiful tries to market its brand by getting Twitter users to rally behind the hashtag. The idea is to encourage women to talk about their bodies and other women’s bodies only in positive terms–and to encourage interaction on Twitter. But why is tweeting, which is entirely text-based, called “speaking”? And what does it mean to speak beautifully, since beauty is usually an issue of body image? In other words, why give this campaign that specific name?

Their promotional video has a clue. As on Twitter, there is no voice, only text; however, there is an instrumental soundtrack throughout. It begins in a minor mode, traditionally associated with negative emotions. Then, around the 0:19 mark, once the blue Dove domino has started knocking down all the white dominoes with negative comments printed on them, the soundtrack shifts to major mode, which is traditionally associated with positive emotions. The video equates social media performance with musical harmony: negative comments are dissonant, positive ones are consonant.

“Speaking beautifully” means adopting the tone or attunement expected of the social media performance. But this still doesn’t tell us why it makes sense for Dove to describe women’s ability to follow social (media) norms as speaking, as making a particular kind of sound. #SpeakBeautiful is just the latest example of a convention that dates back thousands of years: patriarchy moderates women’s literal and metaphoric voices to control their participation in and affect on society, ensuring that these voices don’t disrupt a so-called harmoniously-ordered society. In what follows, I look to the origin of that convention in so we can better understand how it works today.

***

Anne Carson’s essay “The Gender of Sound” focuses mainly on ancient Greek literature and philosophy. “In general,” she argues, “the women of classical literature are a species given to disorderly and uncontrolled outflow of sound” (126). Unless carefully managed by husbands and the law, women’s loose lips (in both senses of the term) will upset overall “harmonious” order of the city. That’s why the ancient Greeks thought women’s disharmonious sounds acted “as political disease” (127).

Emphasizing the relationship the Greeks drew between sonic harmony and social harmony, Carson’s analysis hinges on the concept of sophrosyne; often translated as “moderation,” the ancient Greeks understood sophrosyne as a type of harmony, and often explicitly connected it to musical harmony. Understanding the connection between sophrosyne and ancient Greek theories of musical harmony (which are very different than contemporary European ones) makes it easy to update Carson’s analysis to account for contemporary appraisals of women’s voices, such as the view that some feminist voices on social media are “toxic.”

According to Carson, the ancient Greeks thought women’s voices were immoderate when they exhibited excessive frequency: they could talk either at too high a pitch, or just talk too much. As Carson explains,

verbal continence is an essential feature of the masculine virtue of sophrosyne…[A]ncient discussions of the virtue of sophrosyne demonstrate clearly that, where it is applied to women, this word has a different definition than for men. Female sophrosyne is coextensive with female obedience to male direction and rarely means more than chastity. When it does mean more, the allusion is often to sound. A husband exhorting his wife or concubine to sophrosyne is likely to mean ‘Be quiet!’ (126).

So, (certain kinds of) men were thought to be capable of embodying (masculine) sophrosyne, that is, of comporting their bodies in accord with the order of the city, so that when they did speak, their speech contributed to social harmony and orderliness. The practice of sophrosyne aligns one’s body with the logos of a properly-ordered society, and, indeed, a properly-ordered cosmos. As Judith Periano puts it, moderation “tunes the soul to the cosmic scale (rather than the physical body)” (33). Women (and slaves, and some other kinds of men) were thought to be incapable of embodying this logos, of transforming their bodies into microcosms of the well-ordered city and harmonious cosmos. Their speech would disrupt social and cosmic harmony with dissonant, disorganized material. Silence, then, is how women contributed to social and cosmic harmony: their verbal and sexual chastity preserved the optimal, most well-balanced political and metaphysical order.

“Sanzio 01 Plato Aristotle” by Raphael – Web Gallery of Art: Image Info about artwork. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Women couldn’t embody the logos because they had “the wrong kind of flesh and the wrong alignment of pores for the production of low vocal pitches, no matter how hard they exercised” (Carson 120). Women’s disproportional “alignment of pores” matters, and Ancient Greek music theory is key to understanding why. Though there was widespread disagreement as to the specific ratios that were the most consonant and harmonious, there was a general consensus among music theorists and philosophers that musical harmony was a matter of geometric proportion. For example, Plato says in Timaeus 32c that the cosmos “was harmonized by proportion.” Proportion, for the ancient Greeks is both a ratio and a hierarchical ordering, a relational distribution that is also a series. Plato’s myth of the metals, for example, is both proportional (the “gold” get the most responsibility) and hierarchical (the gold are on the top). There is a right place for everything, and harmony is the effect of everything being in its right, appropriately proportionate place.

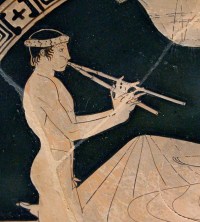

Harmonious sounds are side-effects of harmoniously proportioned material bodies–or rather, sonic harmony occurs when the relationship between an instrument’s internal structure and external emission (e.g., between body and speech) is itself proportionate. For example, on a pipe organ, a pipe’s size is directly and consistently proportional to the pitch it emits, such that the geometric relationships among pipes are directly and consistently proportional to the relationships among pitches. Woodwinds, on the other hand, exhibit no such direct, consistent relationship between material configuration and emitted pitch. On an oboe, the geometric relationship between the instrument as it plays a middle C and a high C does not mirror to the acoustic relationship between those pitches. As Plato puts it “in the case of flute-playing, the harmonies are found not by measurement but by the hit and miss of training, and quite generally music tries to find the measure by observing vibrating strings. So there is a lot of imprecision mixed up in it and very little reliability” (Philebus 56a). Here, he expresses the then-typical view that musical harmony ought to be a mathematically consistent effect of geometric relationships among the instrument’s parts (e.g., vibrating strings). The problem with the flute is that the relationships among its pitches is merely sonic, and cannot be inferred from the geometric relationships among its parts. Its sounds do not exhibit a consistent, proportional, moderate relationship to its material structure.

This is the same problem Carson identifies with women: the orderliness of their vocal emissions cannot be reliably inferred from the visible arrangement of their body and its constitutent parts. Like the flute, a feminine body cannot emit a moderate sound because the proportions of women’s bodies are out of whack; they don’t exhibit the proper ratio between parts, or between inner constitution and outer expression.

“Banquet Euaion Louvre G467 n2” by English: Euaion Painter – Jastrow (2008). Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Women’s voices are “bad to hear or make men uncomfortable” (Carson, 129) not just because the voices themselves are disharmoniously feminine, but because they upset the social and cosmic order, specifically, the balance between inside and outside (129), intelligible and visible. Just as the aulos (an ancient Greek double-reeded instrument, somewhat like a modern oboe) upsets the proper, ideal relationship between an instrument’s physical structure (the part that commands, the mathematical logos of proportionality) and acoustic tuning (the part that obeys, pitches), women’s emissions mess up the proper, logical relationship between “the part that commands and the part that obeys” (Foucault, The History of Sexuality Vol. 2, 87), that is, between inner and outer, soul and body, private and public. Carson says, “By projections and leakages of all kinds–somatic, vocal, emotional, sexual–females expose or expend what should be kept in” (129). Sophrosyne is what keeps things in their right place as they get outwardly expressed.

When men practice “masculine” sophrosyne, they shape their bodies, their resonating innards, so to speak, into a form that will lend itself to rational, proportional outer expression, i.e., speech. Women’s feminine sophrosyne, public silence, keeps their irrational bodies from outwardly expressing disharmonious, disproportionate phenomena that would knock everything out of balance. Masculine sophrosyne is a technique for embodying the logos at the individual, social, and cosmic levels; feminine sophrosyne is a technique for keeping the cosmic/social logos from being disturbed.

Nowadays, though, we don’t expect “good” women to be seen and not heard–we praise (some) women for making the right noises in the right contexts. For example, Rebecca Solnit wrote that 2014 was, for women, “a year of mounting refusal to be silent…It was loud, discordant, and maybe transformative, because important things were said…and heard as never before.” Proclamations of women’s envoicement–of women’s full inclusion and participation in society–are central to post-feminist patriarchy, which functions best when there is a little bit of “feminist” noise mixed in with its signal. The audibility of some women’s “feminist” voices serves as (misleading) evidence that patriarchy is over (or on the way there), and lets patriarchy and the intersectional work it does pass unnoticed. Whereas the ancient Greeks thought women’s voices were absent from a harmonious society, contemporary (neo)liberal democracies think a harmonious society includes a certain amount of feminist noise.

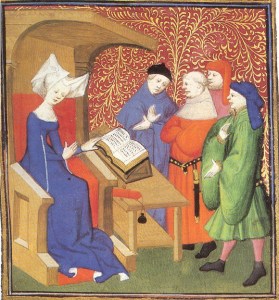

“Christine de Pisan – cathedra” by From compendium of Christine de Pizan’s works, 1413. Produced in her scriptorium in Paris – http://bcm.bc.edu/issues/winter_2010/endnotes/an-educated-lady.html. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

But not too much feminist noise: feminist noise must be moderate. Moderation still matters–it’s just measured differently than it was in ancient Greece. It isn’t a matter of geometric proportion, but of dynamic range. From a post-feminist perspective, feminist voices that call attention to ongoing patriarchy and misogyny feel too loud. Sara Ahmed explains, “words like “racism” and “sexism” are heard as abrasive because they name what has receded from view.” Voices that speak of ongoing racism and sexism are charged with the same flaws attributed to artificially loudened, overcompressed music: inflexibility, lack of variability, and ineffectiveness. Just as overcompressed music is thought to, as Suhas Sreedhar describes “sacrifice…the natural ebb and flow of music,” feminist activists are thought to to sacrifice the natural ebb and flow of social harmony.

In a post-feminist, post-race society, people who continually insist on the existence of sexism and racism appear to be similarly stuck on an irrelevant issue and lacking in expressive range. Similarly, in music lacking dynamic range, “the sound becomes analogous to someone constantly shouting everything he or she says. Not only is all impact lost, but the constant level of the sound is fatiguing to the ear (Sreedhar).” Because it stays more or less fixed at the same amplitude of sound, loud music is thought to be both ineffective and unhealthy for those subjected to it. Similarly, liberal critics of women of color activists often characterize them as hostile, uncivil, or overly aggressive in tone, which supposedly diminishes the impact of their work and both upsets the healthy process of social change and fatigues the public. They are, in Michelle Goldberg’s terms, “toxic.”

This “ebb and flow” is not a geometric proportion, but a frequency or statistical distribution that can be represented as a sine wave. As I have argued here, contemporary concepts of social harmony aren’t based in ancient Greek music theory, but on acoustics. For example, Alex Pentland’s theory of “social physics” or, “the reliable, mathematical connections between information and idea flow…and people’s behavior” (2), treats individual and group behavior as predictable patterns that emerge, as signal, from noisy data streams, just as harmonics and partials emerge from interacting sound frequencies.

In this context, “loud” feminist voices feel like they’re upsetting the ebb and flow, the dynamic range and variability, of information and idea flow. But the thing is, they aren’t upsetting the flow, but intensifying it: their perceived loudness incites others to respond with trolling, harassing, and other kinds of policing speech, often in massive scale. When philosopher Cheryl Abbate told her students that it was unacceptable to express homophobic views in class, John McAdams, a tenured faculty member in the department where Abbate is a doctoral student, wrote a blog post accusing her of inhibiting the free expression of a diverse range of opinions. Her “loud” feminism masked the “healthy diversity” of opinions. McAdams’s post led Abbate to be targeted by a tsunami of harassment, from individuals emailing her, to social media attacks, to attacks from mainstream media and political organizations. When feminist voices make noise, patriarchy amps up its own frequencies to bring the mix back in proper balance so that patriarchy is what emerges from feminist noise. In this context, voices are harmonious when, together, their ebb and flow predictably transmits patriarchal signal into the future. Sophrosyne is a feature of voices that interact so that patriarchal power relations emerge from them: they might actually have an extremely high volume, but they feel moderate because they restore the “normal” ebb and flow of society.

In this context, “loud” feminist voices feel like they’re upsetting the ebb and flow, the dynamic range and variability, of information and idea flow. But the thing is, they aren’t upsetting the flow, but intensifying it: their perceived loudness incites others to respond with trolling, harassing, and other kinds of policing speech, often in massive scale. When philosopher Cheryl Abbate told her students that it was unacceptable to express homophobic views in class, John McAdams, a tenured faculty member in the department where Abbate is a doctoral student, wrote a blog post accusing her of inhibiting the free expression of a diverse range of opinions. Her “loud” feminism masked the “healthy diversity” of opinions. McAdams’s post led Abbate to be targeted by a tsunami of harassment, from individuals emailing her, to social media attacks, to attacks from mainstream media and political organizations. When feminist voices make noise, patriarchy amps up its own frequencies to bring the mix back in proper balance so that patriarchy is what emerges from feminist noise. In this context, voices are harmonious when, together, their ebb and flow predictably transmits patriarchal signal into the future. Sophrosyne is a feature of voices that interact so that patriarchal power relations emerge from them: they might actually have an extremely high volume, but they feel moderate because they restore the “normal” ebb and flow of society.

When Dove and Twitter urge women to “speak beautifully,” they’re really demanding that women practice sophrosyne: that they make just enough ‘feminist’ noise without being too loud–i.e., loud enough to distort the brand image of Unilever and Twitter. So, even though ancient Greek concepts of musical harmony and patriarchy are vastly different than contemporary (neo)liberal democratic ones, each era uses its own version of sophrosyne to shape women’s voices into something consonant with a social order that privileges men and masculinity.

—

Featured image: “” by Flickr user Ed Lynch-Bell, CC BY-NC 2.0

—

Robin James is Associate Professor of Philosophy at UNC Charlotte. She is author of two books: Resilience & Melancholy: pop music, feminism, and neoliberalism, published by Zer0 books last year, and The Conjectural Body: gender, race and the philosophy of music was published by Lexington Books in 2010. Her work on feminism, race, contemporary continental philosophy, pop music, and sound studies has appeared in The New Inquiry, Hypatia, differences, Contemporary Aesthetics, and the Journal of Popular Music Studies. She is also a digital sound artist and musician. She blogs at its-her-factory.com and is a regular contributor to Cyborgology.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

Top 40 Democracy: Taylor Swift’s Election Day Victory—Eric Weisbard

Vocal Gender and the Gendered Soundscape: At the Intersection of Gender Studies and Sound Studies—Christine Ehrick

On Sound and Pleasure: Meditations on the Human Voice– Yvon Bonefant

As Loud As I Want To Be: Gender, Loudness, and Respectability Politics

Editor’s Note: Here’s installment #2 of Sounding Out!‘s blog forum on gender and voice! Last week we hosted Christine Ehrick‘s selections from her forthcoming book; she introduced us to the idea of the gendered soundscape, which she uses in her analysis on women’s radio speech from the 1930s to the 1950s. In the next few weeks we’ll have SO regular writer Regina Bradley, with a look at how music is gendered in Shonda Rhimes’ hit show Scandal, A.O. Roberts with synthesized voices and gender, Art Blake with his reflections on how his experience shifting his voice from feminine to masculine as a transgender man intersects with his work on John Cage, and lastly Robin James with an analysis of how ideas of what women should sound like have roots in Greek philosophy.

Editor’s Note: Here’s installment #2 of Sounding Out!‘s blog forum on gender and voice! Last week we hosted Christine Ehrick‘s selections from her forthcoming book; she introduced us to the idea of the gendered soundscape, which she uses in her analysis on women’s radio speech from the 1930s to the 1950s. In the next few weeks we’ll have SO regular writer Regina Bradley, with a look at how music is gendered in Shonda Rhimes’ hit show Scandal, A.O. Roberts with synthesized voices and gender, Art Blake with his reflections on how his experience shifting his voice from feminine to masculine as a transgender man intersects with his work on John Cage, and lastly Robin James with an analysis of how ideas of what women should sound like have roots in Greek philosophy.

As I planned for SO!’s February forum, I wondered about my own connection to the topic: how is the loudness of a voice gendered? Does it matter who we call “loud”? As a Latina, I’m familiar with the stereotypes of the loud Latina, and as a Puerto Rican I faced them at every gathering. So for this week I decided to reflect upon my experiences in a personal essay. Lean in, close your eyes, and don’t let the voices startle you.–Liana M. Silva, Managing Editor

—

I was 22 years old when someone called me deaf. I was finishing my bachelor’s degree at the University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras campus. After four years of living in San Juan, I still hadn’t gotten used to the class and race microaggressions I encountered regularly because I was a brown girl who grew up in the country and was going to school in the urban capital, el área metropolitana. These microaggressions were usually assumptions about who I was based on how I talked: I called pots a certain way, I referred to nickels in another way, and I couldn’t keep my voice down–all indications, according to my “urban” friends, that I grew up in the country. But being called “deaf” was a new one.

My boyfriend at the time had no cellphone, and his mother would call me regularly to see if he was on his way home from a gig or to ask him to run an errand. She and I were not close, but we were cordial. I always felt we didn’t click on some level. This particular weekend day, she had called to ask if he had left San Juan already to come visit her, and I told her I had just seen him that morning before he left. Somehow she and I went from small talk into a conversation.

In my head, I thought I was making headway with her and that this was a huge step forward in our relationship. We talked about his gig the night before, about how my family was doing, things like that. Then she asked me if my family had a medical history of people losing their hearing. “No? I don’t think so. Why do you ask?” I said in Spanish.

“Because you talk so loud, and so do your father and your sister. Your mom isn’t loud.”

That was over 10 years ago, but the comment still stings. I am certain that wasn’t the only time someone called me “loud” or pointed out the tone of my voice, but it’s the one time that still rings in my ears when I think about the intersection of gender and sound. It wasn’t just that I spoke at a high volume, it was that I was a woman who spoke at a high volume. I was the girlfriend who was loud.

Of course we’re not born loud- or soft-speakers – we learn to use the volume level that prevails in our culture, and then turn it up or lower it depending on our subculture and peer group.

-Anne Karpf, The Human Voice

What does “loud” mean, anyway? Denotations fade into connotations. As I write this, I struggle to think of how to describe loud in a way that doesn’t feel negative. Because every time I think of “loud” its negative connotations float up to the surface. Just take this Merriam-Webster online dictionary entry for “loud.” Aside from the reference to volume, “loud” also means sounds that are offensive, obtrusive—annoying.

To be fair, I’ve always been self-conscious of my voice, and not in the way most people hate the sound of their voice. I always felt my voice was not girly enough. I always felt as a teenager and a young adult not “pretty” enough, not thin enough, not “feminine” enough, so my insecurities also extended to my voice.

Growing up, I heard people tell me time and time again to keep my voice down, that I was talking too loud, that people next door could hear me, et cetera. Grandparents, cousins, parents, friends: I got it from every corner. Shush. But I don’t recall anybody saying that about the boys/men I hung out with. Add to that the comments I got about my appearance: “you’re too fat,” “your hair is too frizzy,” ‘you’re ugly.” I associated being loud with being unattractive. Just another flaw.

It’s no coincidence then that describing a woman as loud is almost never said as a compliment. Although a man can be loud—he might even be expected to have a deep, booming, commanding voice, as the above video describes—when a woman is described as loud, it’s almost never in a good light. Karpf mentions in The Human Voice: The Story of a Remarkable Talent that “Loudness certainly seems to be judged differently depending on the sex of the speaker. Talking loudly is considered an act of aggression in women, but in men as no more than they’re entitled to.” In other words, society deems men to be allowed to be loud, and by extension loudness comes off as a masculine feature. So loudness, something that at its base means high volume, ends up being constructed as more than just decibels. Women who are “loud” become noisy, rude, unapologetic, unbridled.

Mija pero que duro tu hablas.

In Puerto Rico, the word for “loud” was alto (high) but also duro (hard). I knew early on that when someone told me that I spoke duro they didn’t mean it in a kind way. The voice was described as hard, harsh, shards of glass. It hurt to be called loud. It hurt to be called hard. Especially when you understand that society accepts only certain ways of being a woman: soft, delicate, fragile, dainty. It was never meant as a compliment to have someone call your voice “hard.”

If I was listening to my mother and my aunts or cousins speaking, and then chimed in, I would get the “shhhh” or if they wanted to be discreet they would make a gesture with their hands to indicate to me that I should bring my voice down. I learned early on that a lower voice was more appealing than the loud voice hiding in my vocal box.

I am Puerto Rican, and even though I was born in New York City, I was raised in a small town on the western side of Puerto Rico. I was already well-aware of stereotypes and digs about my being born in New York, even at a young age. My cousins would tell me I was stuck up, I thought I was better than other people because I had cable, I only listened to music in English (I guess that was a bad thing to them). When I moved to San Juan, I was no longer a displaced Nuyorican but a country bumpkin. Peers, friends, and new acquaintances would not classify me as a Nuyorican but, because I was living in San Juan at the time, would categorize me as an islander, de la isla, which basically meant I was not from el “area metro.” I was, in short, a country bumpkin to them.

The loudness of my voice was not just a marker of where I came from (the country, with all of the classicism that the phrase entails) but for me became conflated with gender. I knew that even when I wasn’t living in the city, I had been called loud. It’s just that when my peers asked me to lower my voice or to not speak so “duro” it was also because they thought of me as jíbara, country.

Sometimes I would get carried away when I was telling a joke among my female roommates, or I’d be excited to share some news, and eventually someone would tell me to tone it down. Baja la voz. As I reflect upon my college years living with roommates in a crowded apartment in a crowded city, I remember that we often got together and laughed, talked over each other, shouted across the apartment. But I would get carried away and then someone would say something about it. Mira que nos van a mandar a callar. Someone’s gonna tell us to shut up.

It was in college, however, that I learned to modulate my voice. I am physically capable of whispering, but when I spoke in English in a classroom setting (I was an English major in a school whose language of instruction was Spanish) I felt even louder in English. So I made the effort to tone down my voice, literally. I equated English with career, and by extension with my professional persona.

Ultimately, English would be the language I spoke (and still speak) in academic circles; with the language came also the tone and the volume. Men in my classes seemed more often to initiate conversations in my classes, and sometimes even in the ones where they were a minority. Meanwhile, the driven graduate student that I was, I wanted to step in but not stand out because of my voice. I didn’t want to give them (or the professor for that matter) a chance to discount me because I was a loud Puerto Rican woman at an American school. Eventually I learned how to switch back and forth. So did my fellow female classmates.

I remember as a teacher modulating my voice so I would be less loud and less abrasive in a college classroom. I wanted to assert my authority. If some women resort to vocal fry in order to be taken seriously, as this 2014 article in The Atlantic (online) suggests, I resorted to modulating my voice. That was my way of passing: passing for creative elite, passing for feminine, passing for authoritative. I tried to assert my credibility as a burgeoning scholar and professor by tweaking my voice. I laughed a little softer, I spoke a little slower, I sounded a little lower. I teetered between trying to sound feminine and trying to downplay my femininity through my voice.

Was I trying to sound more like the stereotype of a woman so I could be more credible in the classroom? Was this my own version of respectability politics? “Don’t be so loud and they’ll listen to you”?

“White supremacy grants white people the ability to be understood as expressing a dynamic range; whites can legitimately shout because we hear them/ourselves as mainly normalized. At the same time, white supremacy paints black people as always-already too loud.”

-Robin James, “Some philosophical implications of the “loudness war” and its criticisms”

The negative rhetoric about women and loudness is also connected to respectability politics. Take for example the stereotype of the angry black woman (which is in the vicinity of the loud Latina). If women must be delicate and feminine, being loud would be unattractive, unseemly. Loud also means “not being silent,” in other words, speaking when not spoken to. Robin James touches upon “loudness” in contemporary music, and how the turn toward less loud tracks also has to do with racialized ideas about who can speak and who can be loud–in other words, what counts as noise and what counts as harmonious sound. She cites Goldie Taylor’s piece in The Daily Beast about how, regardless of how angry she felt about the racial injustices in the United States, she would never be able to scream and shout without consequences. Loudness is something racialized people cannot afford.

The stereotype of the angry woman points to how the notion of who is loud and what tone of voice is considered loud are constructed. Although there are studies that point out that the sound of one’s voice indicates to others that one is in a position of authority or that one’s voice can make or break one’s career, there is yet to be a study that shows how the biology of the body that produces the voice affects what one can or cannot do. In other words, the connection between voice and our abilities, or our social class, is constructed—in our heads.

Assertive, aggressive, leader: these descriptions benefit men, for the most part. Aggressiveness is seen as a masculine trait, and along with that a loud tone of voice is also seen as masculine. (This idea is also problematic, for it sets anything that isn’t aggressive and assertive as female, and therefore negative.) The opposite applies to women; the same way our society associates fragile delicate things with femininity, a fragile, soft, low tone of voice is the acceptable range for a woman. And James and Taylor’s comments point to how race also changes the equation. Damned if we speak, damned if we don’t.

***

Over the years, I’ve become more comfortable with the way I sound. I’ve also become more comfortable switching between my aural codes, like I do with English, Spanish, and Spanglish. I know that there’s a volume that I use in certain spaces. I also know that in other spaces I don’t have to watch over how loud I am. If I am in a familiar space, with people I am close to, I feel less inclined to watch myself. I feel safe, not judged. I can be as loud as I want to be. But loudness is also an accepted way of speaking around my family. If I spoke in a low tone, I’d probably be picked on for that. My father, for one, has a booming, deep, loud voice, and so do many of my family members.

For me, embracing my voice is also a kind of body acceptance. My body, plus-sized and all, takes up space. My voice takes up space too. As a teenager and an adult I was constantly shamed for the way I look (skin too brown, voice too loud, face too painted, hair too short), and for a time tweaking my voice became a way to try to fit in. But I later learned how to respond to the remarks. I learned to be sarcastic. I learned to make jokes. I learned to talk back. I didn’t find my voice; I embraced my voice.

Dear readers, let us know in the comments: have you been chastised for being loud? Or for not speaking loudly enough?

—

Featured image: property of the author.

—

Liana M. Silva is co-founder and Managing Editor of Sounding Out!.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

I Been On: BaddieBey and Beyoncé’s Sonic Masculinity–Regina Bradley

Learning to Listen Beyond Our Ears: Reflecting Upon World Listening Day—Owen Marshall

An Ear-splitting Cry: Gender, Performance, and Representations of Zaghareet in the U.S.–Meghan Drury

Recent Comments