Technologies of Communal Listening: Resonance at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

In both sound studies and the sonic arts, the concept of “resonance” has increasingly played a central role in attuning listeners to the politics of sound. The term itself is borrowed from acoustics, where resonance simply refers to the transfer of energy between two neighboring objects. For example, plucking a note on one guitar string will cause the other strings to vibrate at a similar frequency. When someone or something makes a sound, everything in the immediate environs—objects, people, the room itself—will respond with sympathetic vibrations. Simply put, in acoustics, resonance describes a sonic connection between sounding objects and their environment. In the arts, the concept of resonance emphasizes the situated existence of sound as a transformative encounter between bodies in a particular time and place. Resonance has become a key term to think through how sound creates a listening community, a transitory assemblage whose reverberations may be felt beyond a single moment of encounter.

For its recent performance series, simply called Resonance, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago drew on this generative concept by bringing together four artists who explore sound as an “introspective force for greater understanding, compassion, and change.” Curated by Tara Aisha Willis and Laura Paige Kyber, the series builds on theories of resonance as an affective relationship between sounding bodies developed by writers and artists like Sonia Louis Davis, Karen Christopher, and Birgit Abels. Crucially, the curators cite composer Juliana Hodkinson’s definition of resonance as an action occurring “when the space between subject and object starts to be reduced, without them fusing into one.” Sound has the capacity for creating a moment of connection, but resonance doesn’t efface difference. As Willis notes in the series program, the artists in the series largely identify as women of color, occupying a position “where distinction and difference are most ingrained in lived experience, and where practice of creating resonance across them are most honed.”

Although the artists in the series, Anita Martine Whitehead, Samita Sinha, Laura Ortman, and 7NMS, are at least partially working within musical traditions, the curators’ framing of the series in terms of sound rather than music speaks to a broader aural turn that has animated both sonic art and scholarship. The essential conceptual move underlying the growth of sound art in the museum and sound studies in the academy is the identification of sound as a medium of expression not fully contained by the history of music. Abstracting from the realm of music to the broader terrain of sound allows these artists to reconsider the materiality of sound and practices of listening—in short, to explore the resonant relations between bodies coexisting in time and space. Yet these pieces do not search for an ahistorical sonic ontology, but instead use sound as a situated tool to forge new social realities in the present. As the artist Samita Sinha puts it, her piece “offers technologies of listening and being together.” Thinking of listening in terms of resonance, we can hear these works as technologies of communal listening.

The series kicked off with the world premiere of Anna Martine Whitehead’s FORCE! an opera in three acts. I attended the evening of March 28, the first of three scheduled performances. Each performance in the series began at 7:30pm at the MCA’s Edlis Neeson Theater. The experimental musical work is an oneiric meditation on the US carceral state centered on the experience of trio of Black femmes passing time in a prison waiting room, ruminating on their dreams, living with state violence, and the unceasing passage of time. Choreographed and co-written by Whitehead, this particular performance of FORCE began with the audience congregated outside the museum’s Edlis Neeson Theater in the transitional space of the lobby, appropriately waiting for the show to start. The opera’s first act took in this space, as a group of performers entered and sat on the grand spiral stairs of the MCA, patiently biding their time. After a few minutes, a mass of four dancers joined them, slowly making their way down the long lobby corridor towards the group on the stairs; their bodies rhythmically moved as one, limbs interlinked and breathing heavy as if burdened by an invisible weight.

The choreography of FORCE continued this motif, as weary bodies became enmeshed, leaning and relying on each other for support. When this phalanx reached the stairwell and laboriously climbed as a unit, the first song began and their voices resonated through the halls of the museum. From there, the audience members were led to the stage not through the theater’s main doors, but through the innards of the museum. Laying the institution bare, the performers led us downstairs through hallways of lockers, then backstage, before we finally took our seats on stage.

The majority of FORCE is then performed on a bare theater stage, the audience in rows encircling the singers and dancers accompanied by a small ensemble of bass, drums, and keys. Just as the audience surrounds the stage, an array of speakers arranged along the edges of the room faces inward to create a shared soundscape inhabited by both the spectators and performers. As an opera, FORCE presents less a linear narrative than a series of songs swirling with reoccurring motifs that, through their repetition, suggest the temporality of waiting. One of the most powerful of these lyrical motifs introduced early in the show is that of fungal growth, of lichens felt on the body, in the nose, and on the eyes. This bivalent image of fungus both points towards an omnipresent carceral power felt on the body, while also recognizing the strategic possibilities of rhizomatic forms. The major theme of the work is of course waiting and time itself, with the singers repeatedly asking how long they have been here—the waiting room, the prison system, the police state—and how much longer they may have yet to go.

While addressing these weighty themes, the work still makes space for the possibility of joy and alternative futures. The performance ends with the singers repeating lines about freedom in a song that never concludes. As we exited, again through the bowels of the MCA, the song reverberated from the theater into the lobby. If FORCE’s first act took place before the audience entered the space of the theater, then the third act likewise continued beyond these four walls as our temporary listening community dispersed into the streets of Chicago. Even after the show, the song did not end.

The second work in the series, Samita Sinha’s Tremor built on these themes of power, space, and sonic connections between resonating bodies. I attended the first of three performances at the MCA on the evening of April 18. Performed on a minimal stage set designed by architect Sunil Bald consisting of three dramatic red sashes suspended from the ceiling, Tremor is an hour-long piece centered on Sinha’s “unraveling” of Indian vocal traditions. Of the artists in this performance series, Sinha perhaps most explicitly explored the theme of resonance, describing her work as “the practice of attuning oneself to the raw material of vibration and its emergence in space, as well as unfolding the possibilities that arise from encounters between this sonic material and other individuals.” In Tremor, the artist is accompanied by the dancer Darrell Jones, vocalist Sunder Ganglani, and an electronic soundscape created live by Ash Fure. As in FORCE, the audience was seated on the stage around the performers, with the shared sonic environment emphasizing the coexistence of our bodies in space.

In broad strokes, Tremor demonstrates the power of sonic community in the face of entropy, presenting a pair of singers competing with a barrage of electronic sound, finding solace in each other’s voice, and ultimately emerging together after an overwhelming onslaught of noise. Accompanied by a low rumble of barely audible sound, the piece begans with the four performers entering the stage and walking in an ever-widening circle, a starting point of social dispersal. Sinha, Ganglani, and Fuhre then took their places at opposing corners of the stage, on cushions placed under the suspended sashes. Jones moved around the center of the stage in ways alternately suggesting ecstasy and pain. The vocalists tentatively began singing wordless vocalizations that tended to resolve to a single note, sometimes accompanied by Sinha’s droning ektara.

As the performance continued, the lights dim and Fure’s electronic sound become increasingly loud and abrasive, a heavily delayed electronic whirring alternately suggesting buzzsaws or heavy machinery. When this noise reached a sustained roaring climax, the dancer and singers moved to the center of the stage, forming a circle with their bodies. Finally, the electronic sound subsides, and the vocalists, led by Sinha, begin singing again—this time with a more supple melody, no longer abrasive vocalizations centered on a single note. This circle of bodies—the performers and we, the audience—have outlasted the assault of noise, co-existing in space, transformed and fortified by this resonant encounter.`

White Mountain Apache sound artist and musician Laura Ortman’s performance marked the release of her latest album, Smoke Rings Shimmers Endless Blur and it provocatively reframes the spatiality of resonance in temporal terms. Ortman performed twice at the MCA, and I attended the first night on April 26. White Mountain Apache sound artist and musician Laura Ortman’s performance marked the release of her latest album, Smoke Rings Shimmers Endless Blur and it provocatively reframes the spatiality of resonance in temporal terms. Where the idea of resonance largely has spatial connotations of synchronic coexistence, Ortman challenges us to think of resonance in terms of time and history through her use of looping sound. Curator Laura Paige Kyber points to this aspect of the artist’s practice, drawing on the work of writers Joseph M. Pierce and Mark Rifkin to argue against the linear time of settler history in favor of “many distinct and self-determined notions of time.” As Kyber suggests, while past histories may resonate through her work, Ortman’s vital sound-making confronts us forcefully in the present.

For her hour-long set, Ortman employed a minimal—but powerful—toolkit for her practice of “sculpting sound”: a single electrified violin run through a pedal board, occasionally supplemented by her voice, a whistle, and a small bell. Throughout the show, the violin was heavily augmented by distortion, delay, and a looping pedal run through a Fender amplifier. Ortman used the loop to build repeating layers of shoegaze-like fuzz over which she improvised on her violin, her bowing veering ecstatically between melodic phrases and rhythmic noise. For most of the performance, she was alone in front of the bare black wall of the Edlis Neeson Theater, with heavy fog machine haze dramatically lit by spotlights and two lines of fluorescent lights on the floor receding into a vanishing point at the back of the stage. She was also accompanied by two short films for the first half: footage of dramatic New Mexico landscapes shot in collaboration with Daniel Hyde and Echota Killsnight, and a video directed by Razelle Benally of Ortman performing in Prospect Park near her home in Brooklyn.

Like Ortman’s music, Benally’s film plays with time, freely shifting between slow motion and double time footage of her performance. Likewise, Ortman’s use of the loop inherently emphasized temporality; with each decaying loop, the past continues to noisily repeat in the present—yet remains with us even as it becomes harder to discern. But amidst the resonance of the past, we are confronted with the artist meeting us in the here and now. We continue to hear the past resonating with is its own distinct temporality and it becomes the basis for Ortman’s vital artistic practice in the present. At the end of her performance, the loops fade away and we are ultimately faced with the artist standing before us sculpting sound with the violin.

The final work in the series, Prophet: The Order of the Lyricist by 7NMS, a collaboration between Marjani Forté-Saunders and Everett Saunders, centered on the figure of the Emcee and the tradition of hip-hop as powerful forces in the Black radical imagination. I attended the May 9 performance. Charting the creative journey of an aspiring lyricist, the piece mixes choreography by Forté-Saunders, an extended spoken-word monologue by Saunders, and a collage of music and sound partially drawn from the Sun Ra Collection at Chicago’s Experimental Sound Studio. Putting the communal ideals of resonance into practice, the artists developed this work in collaboration with the Chicago artistic community, finding inspiration from visits to the city’s South Side Community Arts Center, Stony Island Arts Bank, and Miyagi Records.

The performance begins with a choreographed prelude with Forté-Saunders and dancer Marcella Lewis moving together on a bare stage. Upon Saunders’s entrance onto the stage as the titular lyricist, Forté-Saunders and Lewis largely recede, becoming silent specters, moving through, and occasionally entering the ensuing narrative. In the first section, the lyricist recounted his youth training to be an emcee, adopting an increasingly martial cadence as he described his hard work developing breath control, free-styling, and rhyme-writing skills. This artistic intensity is followed by the most powerful part of the show: a long audio montage of interviews with other lyricists, their voices emanating from speakers surrounding Saunders. As their words ping-ponged from speaker to speaker, the narrator began flinging his body across the stage, before finally collapsing in a roar of white noise and projected static. From there, the lyricist described his further spiritual and political education under the tutelage of “three kings,” wise men he met on the streets of Philadelphia. In the show’s final moments, we watched the emcee frantically writing his lyrics on the stage floor, his words projected, resonating through the auditorium.

The diversity of performances in the series speaks to the capacious power of the concept of resonance, and the continued vitality of sound as a medium of expression. Through the series, sound was employed as a situated tool of connection, convening audience and performer in a communal space without eliding difference.

In her piece, Samita Sinha draws on the thinking of Caribbean philosopher’s Éduoard Glissant’s notion of trembling. Trembling thinking “is the instinctual feeling that we must refuse all categories of fixed and imperial thought … We need trembling thinking – because the world trembles, and our sensibility, our affect trembles … even when I am fighting for my identity, I consider my identity not as the only possible identity in the world.” Airek Beauchamp suggests a similar connection between sound and trembling, writing about the potential for sonic connection between marginalized queer bodies. Beauchamp argues that strategically deployed noise “communicates in trembles, resonating in both the psyche and the actual body,” coalescing disparate identities into a powerful social form. Trembling then, like resonance, doesn’t offer a single solution to global crises—likewise these artists do not treat sound as an inherently revelatory tool of political liberation. But through resonance, understood as a technology of communal listening, the artists invite us to hope for transformative encounters, for new ways of hearing the world.

—

Featured Image: Photo: Rachel Keane on https://mcachicago.org/

—

Harry Burson holds a PhD in Film & Media from the University of California, Berkeley. He researches and teaches on the theory and history of sonic media, exploring the intersection of digital and aural cultures, with particular focus on immersive media, sound art, and VR. His work examines how sound technologies have shaped both our understanding of and embodied relationship to digital media. He is currently a Lecturer at the University of Illinois Chicago (hburson@uic.edu)

—

This article also benefitted from the editorial review of Dahlia Bekong. Thank you!

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig this:

SO! Amplifies: Wu Tsang’s Anthem (2021)—Freddie Cruz Nowell

Freedom Back: Sounding Black Feminist History, Courtesy the Artists–Tavia Nyong’o

My Time in the Bush of Drones: or, 24 Hours at Basilica Hudson–Robert Ryan

The Sound of What Becomes Possible: Language Politics and Jesse Chun’s 술래 SULLAE (2020)—Casey Mecija

Your Voice is (Not) Your Passport

In summer 2021, sound artist, engineer, musician, and educator Johann Diedrick convened a panel at the intersection of racial bias, listening, and AI technology at Pioneerworks in Brooklyn, NY. Diedrick, 2021 Mozilla Creative Media award recipient and creator of such works as Dark Matters, is currently working on identifying the origins of racial bias in voice interface systems. Dark Matters, according to Squeaky Wheel, “exposes the absence of Black speech in the datasets used to train voice interface systems in consumer artificial intelligence products such as Alexa and Siri. Utilizing 3D modeling, sound, and storytelling, the project challenges our communities to grapple with racism and inequity through speech and the spoken word, and how AI systems underserve Black communities.” And now, he’s working with SO! as guest editor for this series (along with ed-in-chief JS!). It kicked off with Amina Abbas-Nazari’s post, helping us to understand how Speech AI systems operate from a very limiting set of assumptions about the human voice. Last week, Golden Owens took a deep historical dive into the racialized sound of servitude in America and how this impacts Intelligent Virtual Assistants. Today, Michelle Pfeifer explores how some nations are attempting to draw sonic borders, despite the fact that voices are not passports.–JS

—

In the 1992 Hollywood film Sneakers, depicting a group of hackers led by Robert Redford performing a heist, one of the central security architectures the group needs to get around is a voice verification system. A computer screen asks for verification by voice and Robert Redford uses a “faked” tape recording that says “Hi, my name is Werner Brandes. My voice is my passport. Verify me.” The hack is successful and Redford can pass through the securely locked door to continue the heist. Looking back at the scene today it is a striking early representation of the phenomenon we now call a “deep fake” but also, to get directly at the topic of this post, the utter ubiquity of voice ID for security purposes in this 30-year-old imagined future.

In 2018, The Intercept reported that Amazon filed a patent to analyze and recognize user’s accents to determine their ethnic origin, raising suspicion that this data could be accessed and used by police and immigration enforcement. While Amazon seemed most interested in using voice data for targeting users for discriminatory advertising, the jump to increasing surveillance seemed frighteningly close, especially because people’s affective and emotional states are already being used for the development of voice profiling and voice prints that expand surveillance and discrimination. For example, voice prints of incarcerated people are collected and extracted to build databases of calls that include the voices of people on the other end of the line.

“Collect Calls From Prison” by Flickr User Cobalt123 (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

What strikes me most about these vocal identification and recognition technologies is how their appeal seems to lie, for advertisers, surveillers, and policers alike that voice is an attractive method to access someone’s identity. Supposedly there are less possibilities to evade or obfuscate identification when it is performed via the voice. It “is seen as a solution that makes it nearly impossible for people to hide their feelings or evade their identities.” The voice here works as an identification document, as a passport. While passports can be lost or forged, accent supposedly gives access to the identity of a person that is innate, unchanging, and tied to the body. But passports are not only identification documents. They are also media of mobility, globally unequally distributed, that allow or inhibit movement across borders. States want to know who crosses their borders, who enters and leaves their territory, increasingly so in the name of security.

What, then, when the voice becomes a passport? Voice recognition systems used in asylum administration in the Global North show what is at stake when the voice, and more specifically language and dialect, come to stand in for a person’s official national identity. Several states including Denmark, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Sweden, as well as Australia and Canada have been experimenting with establishing the voice, or more precisely language and dialect, to take on the passport’s role of identifying and excluding people.

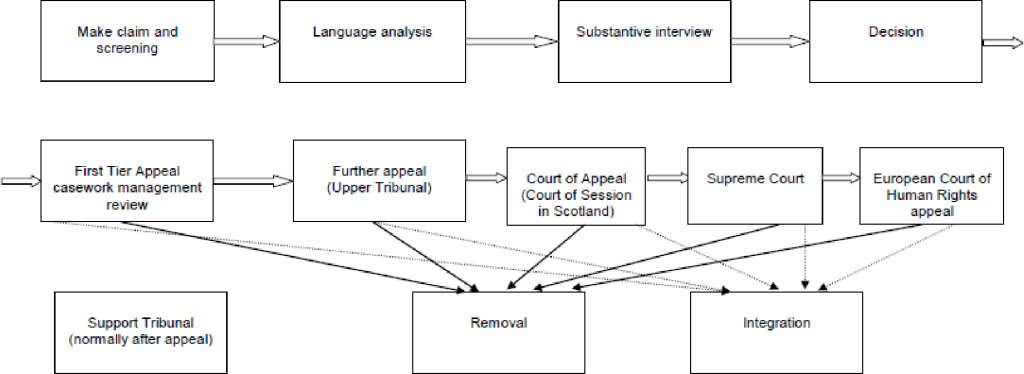

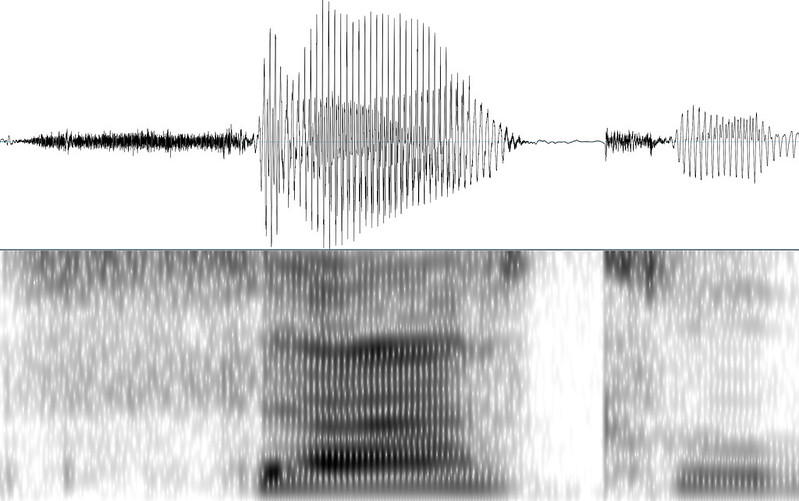

In the 1990s—not too far from the time of Sneakers release—they started to use a crude form of linguistic analysis, later termed Language Analysis for the Determination of Origin (LADO), as part of the administration of claims to asylum. In cases where people could not provide a form of identity documentation or when those documents would be considered fraudulent or inauthentic, caseworkers would look for this national identity in the languages and dialects of people. LADO analyzes acoustic and phonetic features of recorded speech samples in relation to phonetics, morphology, syntax, and lexicon, as well as intonation and pronunciation.

The problems and assumptions of this linguistic analysis are multiple as pointed out and critiqued by linguists. 1) it falsely ties language to territorial and geopolitical boundaries and assumes that language is intimately tied to a place of origin according to a language ideology that maps linguistic boundaries onto geographical boundaries. Nation-state borders on the African continent and in the Middle East were drawn by colonial powers without considerations of linguistic communities. 2) LADO thinks of language and dialect as static, monoglossic and a stable index of identity. These assumptions produce the idea of a linguistic passport in which language is supposed to function as a form of official state identification that distributes possibilities and impossibilities of movement and mobility. As a result, the voice becomes a passport and it simultaneously functions as a border, by inscribing language into territoriality. As Lawrence Abu Hamdan has written and shown through his sound art work The Freedom of Speech itself, LADO functions to control territory, produce national space, and attempts to establish a correlation between voice and citizenship.

I’ll add that the very idea of a passport has a history rooted in forms of colonial governance and population control and the modern nation-state and territorial borders. The body is intimately tied to the history of passports and biometrics. For example, German colonial administrators in South-West Africa, present day Namibia, and German overseas colony from 1884 to 1919 instituted a pass batch system to control the mobility of Indigenous people, create an exploitable labor force, and institute and reinforce white supremacy and colonial exploitation. Media and Black Studies scholar Simone Browne describes biometrics as “digital epidermalization,” to describe how surveillance becomes inscribed and encoded on the skin. Now, it’s coming for the voice too.

In 2016 the German government took LADO a step further and started to use what they call a voice biometric software that supposedly identifies the place of origin of people who are seeking asylum. Someone’s spoken dialect is supposedly recognized and verified on the basis of speech recordings with an average lengths of 25,7 seconds by a software employed by the German Ministry for Migration and Refugees (in German abbreviated as BAMF). The now used dialect recognition software used by German asylum administrators distinguishes between 4 large Arabic dialect groups: Levantine, Maghreb, Iraqi, Egyptian, and Gulf dialect. Just recently this was expanded with language models for Farsi, Dari and Pashto. There are plans to expand this software usage to other European countries, evidenced by BAMF traveling to other countries to demonstrate their software.

This “branding” of BAMF’s software stands in stark contradiction to its functionality. The software’s error rate is 20 percent. It is based on a speech sample as short as 26 seconds. People are asked to describe pictures while their speech is recorded, the software then indicates a percentage of probability of the spoken dialect and produces a score sheet that could indicate the following: 74% Egyptian, 13% Levantine, 8% Gulf Arabic, 5 % Other. The interpretation of results is left to the caseworkers without clear instructions on how to weigh those percentages against each other. The discretion left to caseworkers makes it more difficult to appeal asylum decisions. According to the Ministry, the results are supposed to give indications and clues about someone’s origin and are not a decision-making tool. However, as I have argued elsewhere, algorithmic or so-called “intelligent” bordering practices assume neutrality and objectivity and thereby conceal forms of discrimination embedded in technologies. In the case of dialect recognition the score sheet’s indicated probabilities produce a seeming objectivity that might sway case-workers in one direction or another. Moreover, the software encodes distinctions between who is deserving of protection and who is not; a feature of asylum and refugee protection regimes critiqued by many working in the field.

The functionality and operations of the software are also intentionally obscured. Research and sound artist Pedro Oliveira addresses the many black-boxed assumptions entering the dialect recognition technology. For instance, in his work Das hätte nicht passieren dürfen he engages with the labor involved in producing sound archives and speech corpora and challenges “ the idea that it might be feasible, for the purposes of biometric assessment, to divorce a sound’s materiality from its constitution as a cultural phenomenon.” Oliveira’s work counters the lack of transparency and accountability of the BAMF software. Information about its functionality is scarce. Freedom of information requests and parliamentary inquiries about the technical and algorithmic properties and training data of the software were denied as the information was classified because “the information can be used to prepare conscious acts of deception in the asylum proceeding and misuse language recognition for manipulation,” the German government argued. While it is not necessarily deepfakes like the one Brandes produced to forego a security system that the German authorities are worried about, the specter of manipulation of the software looms large.

The consequences of the software’s poor functionality can have drastic consequences for asylum decisions. Vice reported in 2018 the story of Hajar, whose name was changed to protect his identity. Hajar’s asylum application in Germany was denied on the basis of a dialect recognition software that supposedly indicated that he was a Turkish speaker and, thus, could not be from the Autonomous Region Kurdistan as he claimed. Hajar who speaks the Kurdish dialect Sorani had been instructed by BAMF to speak into a telephone receiver and describe an image in his first language. The software’s results indicated a 63% probability that Hajar speaks Turkish and the caseworker concluded that Hajar had lied in his asylum hearings about his origin and his reasons to seek asylum in Germany who continued to appeal the asylum decision. The software is not equipped to verify Sorani and should not have been used on Hajar in the first place.

Why the voice? It seems that bureaucrats and caseworkers saw it as a way to identify people with ease and scale language analysis more easily. It is also important to consider the context in which this so-called voice biometry is used. Many people who seek asylum in Germany cannot provide identity documents like passports, birth certificates, or identification cards. This is the case because people cannot take them with them as they flee, they are lost or stolen on people’s journeys, or they are confiscated by traffickers. Many forms of documentation are also not accepted as legitimate by state authorities. Generally, language analysis is used in a hostile political context in which claims to asylum are increasingly treated with suspicion.

The voice as a part of the body was supposed to provide an answer to this administrative problem of states. In response to the long summer of migration in 2015 Germany hired McKinsey to overhaul their administrative processes, save money, accelerate asylum procedures, and make them more “efficient.” In July 2017, the head of the Department for Infrastructure and Information Technology of the German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees hailed the office’s new voice and dialect recognition software as “unrivaled world-wide” in its capacity to determine the region of origin of asylum seekers and to “detect inconsistencies” in narratives about their need for protection. More than identification documents, personal narratives, or other features of the body, the voice, the BAMF expert suggests is the medium that allows for the indisputable verification of migrants’ claims to asylum, ostensibly pinpointing their place of origin.

Voice and dialect recognition technology are established by policy makers and security industries as particularly successful tools to produce authentic evidence about the origin of asylum seekers. Asylum seekers have to sound like being from a region that warrants their claims to asylum: requiring the translation of voices into geographical locations. As a result, automated dialect recognition becomes more valuable than someone’s testimony. In other words, the voice, abstracted into a percentage, becomes the testimony. Here, the software, similarly to other biometric security systems, is framed as more objective, neutral, and efficient way of identifying the country of origin of people as compared to human decision-makers. As the German Migration agency argued in 2017: “The IT supported, automated voice biometric analysis provides an independent, objective and large-scale method for the verification of the indicated origin.”

The use of dialect recognition puts forth an understanding of the voice and language that pinpoints someone’s origin to a certain place, without a doubt and without considering how someone’s movement or history. In this sense, the software inscribes a vision of a sedentary, ahistorical, static, fixed, and abstracted human into its operations. As a result, geographical borders become reinforced and policed as fixed boundaries of territorial sovereignty. This vision of the voice ignores multiple mobilities and (post)colonial histories and reinscribes the borders of nation-states that reproduce racial violence globally. Dialect recognition reproduces precarity for people seeking asylum. As I have shown elsewhere, in the absence of other forms of identification and the presence of generalized suspicion of asylum claims, accent accumulates value while the content of testimony becomes devalued. Asylum applicants are placed in a double bind, simultaneously being incited to speak during asylum procedures and having their testimony scrutinized and placed under general suspicion.

Similar to conventional passports, the linguistic passport also represents a structurally unequal and discriminatory regime that needs to be abolished. The software was framed as providing a technical solution to a political problem that intensifies the violence of borders. We need to shift to pose other questions as well. What do we want to listen to? How could we listen differently? How could we build a world in which nation-states and passports are abolished and the voice is not a passport but can be appreciated in its multiplicity, heteroglossia, and malleability? How do we want to live together on a planet increasingly becoming uninhabitable?

—

Featured Image: Voice Print Sample–Image from US NIST

—

Michelle Pfeifer is postdoctoral fellow in Artificial Intelligence, Emerging Technologies, and Social Change at Technische Universität Dresden in the Chair of Digital Cultures and Societal Change. Their research is located at the intersections of (digital) media technology, migration and border studies, and gender and sexuality studies and explores the role of media technology in the production of legal and political knowledge amidst struggles over mobility and movement(s) in postcolonial Europe. Michelle is writing a book titled Data on the Move Voice, Algorithms, and Asylum in Digital Borderlands that analyses how state classifications of race, origin, and population are reformulated through the digital policing of constant global displacement.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“Hey Google, Talk Like Issa”: Black Voiced Digital Assistants and the Reshaping of Racial Labor–Golden Owens

Beyond the Every Day: Vocal Potential in AI Mediated Communication –Amina Abbas-Nazari

Voice as Ecology: Voice Donation, Materiality, Identity–Steph Ceraso

The Sound of What Becomes Possible: Language Politics and Jesse Chun’s 술래 SULLAE (2020)—Casey Mecija

The Sonic Roots of Surveillance Society: Intimacy, Mobility, and Radio–Kathleen Battles

Acousmatic Surveillance and Big Data–Robin James

Recent Comments