Listening in Plain Sight: The Enduring Influence of U.S. Air Guitar

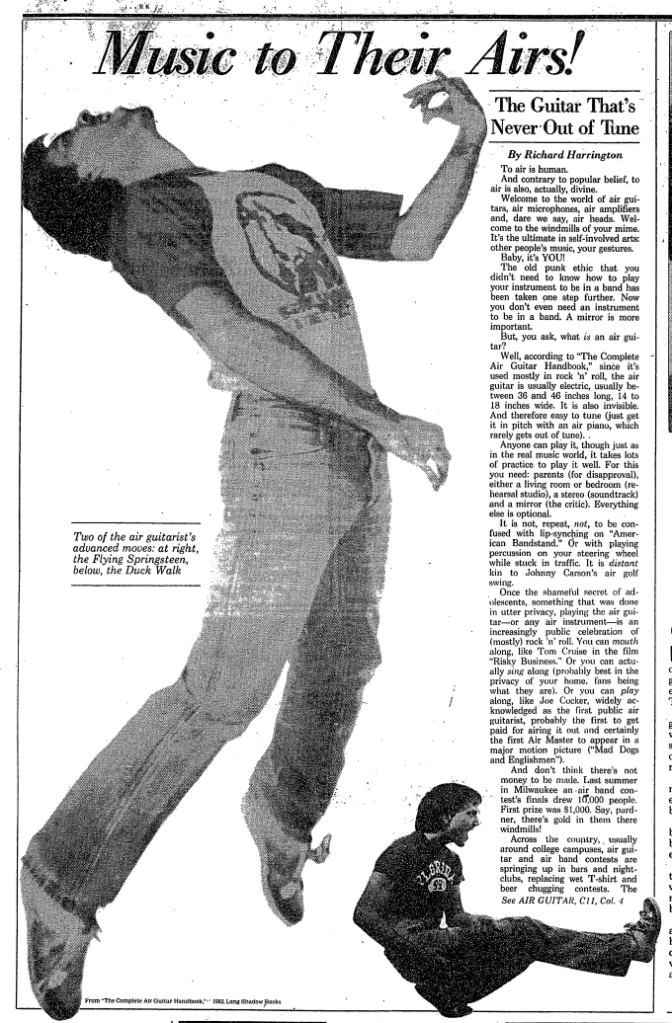

The mention of “air guitar” might conjure images of the Bill and Ted series. Or Risky Business. Or maybe even Joe Cocker at Woodstock. You might think of air guitar as an embarrassing fan gesture. So when you hear there’s an annual U.S. Air Guitar competition, you might imagine an entirely superficial practice without any artistic merit. Maybe you just think of it as gimmicky. Or a celebration of the worst aspects of classic rock fandom and the white male guitar heroes that often populate its pantheon. In all honesty, I thought all of these things at first, until I began to take the competition seriously.

I did not realize, for example, that air guitar competitions have an enduring history since the late 1970s, existing as an incredibly influential popular music pantomime practice that informs platforms like TikTok. I did not realize how invested contemporary competitors could be—dedicating years to learning the craft. And I did not realize how these reconstructions of guitar solos could creatively rupture the relationship between guitar virtuosity and privileged identities in popular music’s past.

The U.S. Air Guitar Championships began in 2003 as the national branch of the Air Guitar World Championships, which began in 1996 in Oulu, Finland. The competition emerged as a bit of a joke alongside the Oulu Music Video Festival. Eventually, two people—Cedric Devitt and Kriston Rucker—founded U.S. Air Guitar, which expanded across the country (thanks, in part, to the influential documentary Air Guitar Nation). Today, folks compete in order to advance from local to regional to the national competition, ultimately hoping to be crowned the best air guitarist in the nation and sent to Finland to represent the United States (think: Eurovision but air guitar). United States air guitarists do incredibly well in the international competition, although they face formidable air guitarists from Japan, France, Canada, Australia, Russia, and Germany (as well as less-formidable air guitarists from elsewhere).

In each competition, competitors perform as personas, such as Rockness Monster, AIRistotle, Agnes Young, and Mom Jeans Jeanie. They don elaborate costumes. They painstakingly practice elaborate choreographies and compete in some of the most famous musical venues in the country—from Bowery Ballroom to the Black Cat. Competitors stage routines that bring a particular 60-second rock solo to life, using their bodies to simulate playing the real guitar (what air guitarists call “there guitar”). Think of these as gestural interpretations of the affective power of guitar solos, rather than a mechanical reproduction of particular chords, frets, and licks. They use their bodies to draw out timbre, rhythm, and pitch, and they also play with the juxtaposition of their own identities and those of the original artists. Judges evaluate performances based on three criteria:

· Technical merit (does the pantomime more or less correspond to the guitar playing in the music?)

· Stage presence (is it entertaining?)

· ‘Airness’ (does the performance transcend the imitation of the real guitar to become an art form in and of itself?)

Scores are given on a figure skating scale, from 4 to 6. So a perfect score is 666 from the three judges. Winners in the first round advance to the second round, where they must improvise an air guitar routine to a surprise song selection.

As part of my ethnographic work on air guitar, I competed in a local competition, where I was crowned third best air guitarist in Boston in the year 2017 (a distinction that will likely never appear on my CV). I have also conducted fieldwork in Finland twice and attended countless competitions in the U.S. I judged the 2019 U.S. Air Guitar Championships in Nashville alongside Edward Snowden’s lawyer, which resulted in a three-way air off to crown a winner.

Competitions depend on recruiting new competitors, celebrity judges, and large crowds, all of which can be at odds with creating an inclusive community. Organizers have worked hard to eliminate racist, sexist, ableist, and other forms of discriminatory language from judges’ comments. Women within U.S. air guitar have formed advocacy groups. The proceeds of the most recent competitions have been donated to Alabama Appleseed Center for Law and Justice, which took up the case of a disabled Black veteran named Sean Worsley who was incarcerated for playing air guitar to music at a gas station. Both organizing bodies at the national and international level emphasize world peace as central to their mission.

Air guitar routines are themselves political statements too. These acts of musical interpretation enable women, BIPOC, and disabled performers to author sounds credited to guitar idols, like Eddie Van Halen or Slash. Performers make arguments about their access to popular music, using only their bodies. Sydney Hutchinson’s work examines how air guitar can challenge Asian American stereotypes and gendered conceptions of dance.

My current work revolves around disabled air guitarists. Andres SevogiAIR drew me in, as a result of his expressive flamenco-inspired seated style he called “chair guitar.” He passed away but left me with an enduring appreciation for air guitar’s ability to challenge conventional virtuosity, a term that can often reproduce an ableist link between physical ability and musical virtue. I came to appreciate how air guitarists could invent imaginary instruments that serve their particular bodies. I witnessed competitors coupling chronic illness and impairments with air guitar routines, as well as competitors using air guitar to fully amplify their struggles with cancer.

I also came to appreciate how air guitarists embrace stigma (e.g., madness, craziness, and gendered forms of listening), turning taboo into a source of creativity. This led to academic writing that traces the history of madness in relation to air guitar, showing how imaginary instrument playing has often been pathologized, and yet contemporary disabled air guitarists reclaim these accusations of insanity as a source of power.

* * *

A few weeks ago, I received a request from Lieutenant Facemelter to judge the Midwestern Online Regional U.S. Air Guitar Competition. I accepted. As with many things these days, the contemporary competition has morphed into a Twitch-hosted online spectacle, featuring combinations of live and pre-recorded elements. One woman gave birth between first- and second-round performances (made possible by a multi-day filming period for an asynchronous part of the online competition). One man’s air guitar performance evoked an exorcism in his basement. Another middle-aged competitor competed while suffering the side effects of his second shot of coronavirus vaccine, ultimately winning the competition with a pro-vaccination message. His parents appeared in the livestream when he accepted the award, and the host of the show–the Master of Airimonies–jokingly said to them: “You two must be so proud.”

I think of U.S. Air Guitar as a stained-glass window, through which prisms of popular music history shine through. The competition can bring troubling facets of that history to light, but the competition can also revise that history (or, at least, reimagine how that history can influence the future). Either way, performers celebrate the idea that rock solos live most powerfully in the embodied listening practices of everyday people. Listening becomes the subject of these performances–the source material for these persuasive displays of music reception. Indeed, air guitar can be one of the strangest things you’ll never see.

The competition continues this summer.

—

Featured Image: US Air Guitar National Finals, The Midland Theater, Kansas City, MO, August 9, 2014, by Flickr user Amber, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

—

Byrd McDaniel | Byrd is a scholar who researches disability, digital cultures, and popular music. He currently works as a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry at Emory University. His forthcoming book–Spectacular Listening— traces the rise of contemporary practices that treat listening as a performance, including air guitar, podcasts, reaction videos, and lip syncing apps. Byrd is enthusiastic about work that addresses any facet of air guitar, including global and historical approaches. He welcomes outreach from those who want to research these topics.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

SO! Reads: Steph Ceraso’s Sounding Composition: Multimodal Pedagogies for Embodied Listening–Airek Beauchamp

Digital Analogies: Techniques of Sonic Play–Roger Moseley

Experiments in Aural Resistance: Nordic Role-Playing, Community, and Sound—Aaron Trammell

Recent Comments