Critical bandwidths: hearing #metoo and the construction of a listening public on the web

“A focus on listening [with technology] shifts the idea of freedom of speech from having a platform of expression to having the possibility of communication” (K. Lacey)

One of the biggest social media event of the past decade, #metoo stands out as a pivotal shift in the future of gender relations. Despite its persistence since October 2017, #metoo is still under-theorized, and since its permutations generate countless hashtag sub-categories each passing week, making sense of it presents a conceptual quagmire. Tracing its history, identifying key moments, mapping its pro- and counter-currents present equally tough challenges to both data science and feminist scholars.

Meta-communication about #metoo abounds. Infographics and visualizations attempt to contain its organic growth into perceivable maps and charts; pop news media constantly report on its evolution in likes, counts, and retweets, as well as—and increasingly—in number of convictions, lawsuits, and reports. At the same time, #metoo has arguably created a discernible listening public in the way that Kate Lacey (2013) argues emerged with national radio: women’s stories have never been listened to with such wide reach and rapt attention.

The project I discuss here takes ‘hearing’ #metoo a step further into the auditory realm in the form of data sonification so as to to re-imagine an audience compelled to earwitness not just the scope but the emotional impact of women’s stories. Data sonification is a growing field, which from its inception has crossed between art and science. It involves a conceptual or semantic translation of data into relevant sonic parameters in a way that utilizes perceptual gestalts to convey information through sound.

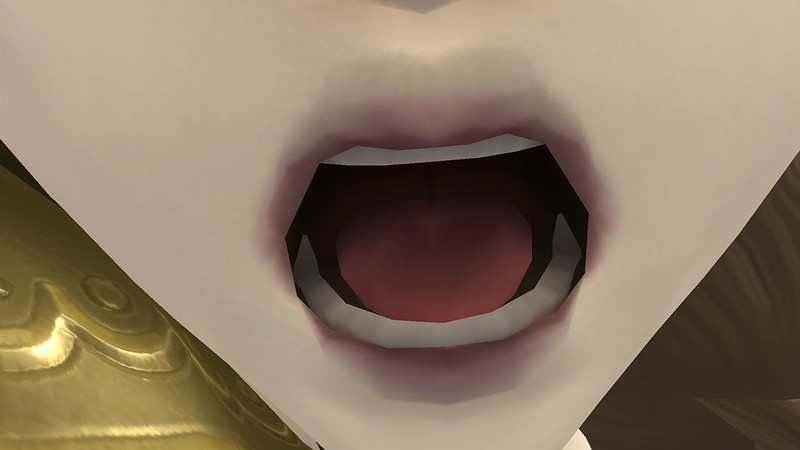

Brady Marks and I created the #metoo sonification you’ll hear below by drawing from a public dataset spanning October 2017 to the early Spring of 2018 obtained from data.world. Individual tweets using the hashtag are sonified using female battle cries from video games; the number of retweets and followers forms a sort of swelling and contracting background vocal texture to represent the reach of each message. The dataset is then sped up anywhere between 10x to 1000x in order to represent perceivable ebbs and flows of the hashtag’s life over time. The deliberate aim in this design was to convey a different sensibility of social media content, one that demands emotional and intellectual attention over a duration of time. Given Twitter’s visual zeitgeist whereby individual tweets are perceived at a glance and quickly become lost in the noise of the platform the affective attitude towards “contagious” events becomes arguably impersonal. A sonification such as this asks the listener to spend 30 minutes listening to 1 month of #metoo: something impossible to achieve on the actual platform, or in a single visualization. The aim, then, is to interrupt social media’s habitual and disposable engagements with pressing civic debates.

A critique of big data visualization

To date, there have been more than 19 million #MeToo tweets from over 85 countries; on Facebook more than 24 million people participated in the conversation by posting, reacting, and commenting over 77 million times since October 15, 2017. In a global information society ‘big data’ is translated into creative infographics in order to simultaneously educate an overwhelmed public and elicit urgency and accord for political action. Yet ideological and political considerations around the design of visual information have lagged behind enthusiasm for making data ‘easy to understand’. At the other end of the spectrum, social media delivers personalized micro-trends directly and in real time to always-mobile users, reinforcing their information silos (Rambukkana 2015). Between these extremes, the mechanisms by which relevant local, marginalized or emergent issues come to be communicated to the wider public are constrained.

With this big idea in mind, the question we ask here is what would it mean to hear data? Emergent work in sonification suggests that sound may afford a unique way to experience large-scale data suitable for raising public awareness of important current issues (Winters & Weinberg 2015). The uptake of sonification by the artistic community (see Rory Viner, Robert Alexander, among many others) signals its strengths in producing affective associations to data for non-specialized audiences, despite its shortcomings as a scientific analysis tool (Supper, 2018). Some of the more esoteric uses of sonification have been in the service of capturing what Supper calls ‘the sublime’ – as in Margaret Schedel’s “Sounds of Science: The Mystique of Sonification.”

Who’s listening on social media?

Within the Western canon of sound studies “constitutive technicities” (Gallope 2011) or what Sterne calls “perceptual technics” embody historically situated ways of listening that center technology as a co-defining factor in our relationship with sound. Within this frame, media sociologist Kate Lacey traces the emergence of the modern listening public through the history of radio. Using the metaphor of ‘listening in” and “listening out,” Lacey reframes media citizenship by pointing out that listening is a cultural as well as a perceptual act with defined political dimensions:

Listening out is the practice of being open to the multiplicity of texts and voices and thinking of texts in the context of and in relation to a difference and how they resonate across time and in different spaces. But at the same time, it is the practice and experience of living in a media age that produces and heightens the requirement, the context, the responsibilities and the possibilities of listening out (198)

According to Lacey, a focus on listening instead of spectatorship challenges the implicit active/passive dualism of civic participation in Western contexts. More importantly, she argues, we need to move away from the notion of “giving voice” and instead create meaningful possibilities to listen, in a political sense. Data sonification doesn’t so much ‘give voice to the voiceless’ but creates a novel relationship to perceiving larger patterns and movements.

Our interactions with media, therefore, are always already presumptive of particular dialogical relations. Every speech act, every message implies a listening audience that will resonate understanding. In other words, how are we already listening in to #metoo? How and why might data sonification enable us to “listen out” for it instead? In order to get a different hearing, what should #metoo sound like?

Sonifying #metoo: the battle cries of gender-based violence

It is unrealistic to expect that your everyday person will read large archives of testimony on sexual harassment and gender-based violence. Because of their massive scale, archives of #metoo testimony pose a significant challenge to the possibility for meaningful communication around this issue. Essentially drowning each other out, individual voices remain unheard in the zeitgeist of media platforms that automates quantification while speeding up engagement with individual contributions. To reaffirm the importance of voice would mean to reaffirm inter-subjectivity and to recognize polyphony as an “existential position of humanity” (Ihde 2007, 178). This was the problem to sonify here: how to retain individual voices while creating the possibility for listening to the whole issue at hand. Inspired by the idea of listening out, myself and artist collaborator Brady Marks set out to sonify #metoo as a way of eliciting the possibility for a new listening public.

The #metoo sonification project intersected deeply with my work on the female voice in videogames. My choice to use a mixed selection of battle cry samples from Soul Calibur, an arcade fighting game, was intuitive. Battle cries are pre-recorded banks of combat sounds that video game characters perform in the course of the story. Instances of #metoo on Twitter presumably represent the experiences of individual women, pumping a virtual fist in the air, no longer silent about the realities of gender-based violence. So hearing #metoo posts as battle cries of powerful game heroines made sense to me. But it’s the meta layers of meaning that are even more intuitive: as I’ve discussed elsewhere, female battle cries are notoriously gendered and sexualized. Listening to a reel of sampled battle cries is almost indistinguishable from listening to a pornographic soundscape. Abstracted in this sonification, away from the cartoonish hyper-reality of a game world, these voices are even more eerie, giving almost physical substance to the subject matter of #metoo. Just as the female voice in media secretly fulfils the furtive desires of the “neglected erogenous zone” of the ear (Pettman 2017, 17), #metoo is an embodiment of the conflation of sex with consent: the basis of what we now call ‘rape culture.’

Sonifying real-time data such as Twitter presents not only semantic (how should it sound like) but also time-scale challenges. If we are to sonify a month – e.g. the month of November 2017 (just weeks after the explosion of #metoo) – but we don’t want to spend a month listening, then that involves some conceptual time-scaling. Time-scaling means speeding up instances that already happen multiple times a second on a platform as instantaneous and global as Twitter. Below are samples of three different sonifications of #metoo data, following different moments in the initial explosion of the hashtag and rendered at different time compressions. Listen to them one at a time and note your sensual and emotive experience of tweets closer to real-time playback, compared to the audible patterns that emerge from compressing longer periods of time inside the same length audio file. You might find that the density is different. Closer to real-time the battle cries are more distinctive, while at higher time compressions what emerges instead is an expanding and contracting polyphonic texture.

Vocalizations of female pleasure/affect, video game battle cries already have a special relationship to technologies of audio sampling and digital reproduction as Corbett & Kapsalis describe in “Aural sex: the female orgasm in popular sound.” This means that the perceptual technics involved in listening to recorded female voices are already coded with sexual connotations. Battle cries in games are purposely exaggerated so as to carry the bulk of emotional content in the game’s experiential matrix. Roland Barthes’ notion of the “grain of the voice”—the presence of the body in (singing) voice—is frequently evoked in describing the substantive role that game voices play in the construction of game world immersion and realism. In the #metoo sonification, I decontextualize the grain of the voice—there are no visual images, narrative, or gameplay; the battle cries are also acousmatic, in that there are no bodies visually represented from which these sounds emanate.

The battle cry in this #metoo sonification is the ultimate disembodied voice, resisting what Kaja Silverman (1988) calls the “norm of synchronization” with a female body in The Acoustic Mirror (83). As acousmatic voices, these battle cries could be said to exist on a different conceptual and perceptual plane, “disturbing the taxonomies upon which patriarchy depends,” to quote Dominic Pettman in Sonic Intimacy. (22). In other words, the sounds exist in a boundary space between combat sounds and orgasmic sounds highlighting for the listener the dissonance between the supposed empowerment of ‘speaking out’ within a culture that remains staunchly set up to sexualize women; something one can hardly ignore given the media’s reserved treatment of #metoo.

Liberated from the game world these voices now speak for themselves in the #metoo sonification, their sensuality all the more hyper-real. The player has no control here, as the battle cries are not linked to specific game actions, rather they are synchronized autonomously to instances of #metoo confessionals. In fact, the density of the sonification as time speeds up will overwhelm listeners with its boundlessness; echoing how contemporary media treats the sounds of the female orgasm as a renewable and inexhaustible resource, even as reports of sexual harassment and gender-based violence continue to pile on in 2021. Yet we intend that the subject matter resists pleasure, rendering the sonic experience traumatic as the chilling realization sets in that listeners are hailed to accountability by #metoo. The experience should instead be unsettling, impactful, grotesque, and deeply embodied.

Concluding remarks

Listening both metaphorically and literally goes to the very heart of questions to do with the politics and experience of living and communicating in the media age. In her paper on the sonic geographies of the voice, AM Kanngieser notes in “A Sonic Geography of Voice“: “The voice, in its expression of affective and ethico-political forces, creates worlds” (337). It is not just in the grain but in the enunciation that battle cries find their political significance in this sonification. As the hyper-real gasps and moans of game heroines animate individual moments of #metoo the codification of cartoonish voices resists being subconsciously “absorbed into the dialogic exchange” (342) of habitual media consumption. Listening to the sonification is instead an experience of re-coding the voice, reconfiguring the embedded meanings of game sound to a new and contradictory context: a space that challenges neoliberal appropriations of radical communication and discourse (348). This is not data sonification that delights the listener or simply grants them access to ‘information’ in a different format; rather it calls on the listener to de-normalize their received technicity and perceptions and to connect to the emotional inter-subjectivity of this call to action.

Most importantly, the #metoo sonification invites the auditeur to listen in, to take an active role in the reconfiguration of meanings and absorb their political dimensions. These are the stories of #metoo; these are the voices of women, of men, of marginalized peoples, emerging from the zeitgeist of Twitter to ask us to earwitness gender-based violence. We are a new listening public, wanting and needing to create new worlds. A critical bandwidth is the smallest perceivable unit of auditory change, in psychology terms. This sonification begs the question, how many battle cries will it take for us to end gender-based violence by fostering equitable worlds?

—

Featured Image: “Listen to What You See” by Flickr User Hernán Piñera (CC BY-SA 2.0)

—

Milena Droumeva is an Assistant Professor and the Glenfraser Endowed Professor in Sound Studies at Simon Fraser University specializing in mobile media, sound studies, gender, and sensory ethnography. Milena has worked extensively in educational research on game-based learning and computational literacy, formerly as a post-doctoral fellow at the Institute for Research on Digital Learning at York University. Milena has a background in acoustic ecology and works across the fields of urban soundscape research, sonification for public engagement, as well as gender and sound in video games. Current research projects include sound ethnographies of the city (livable soundscapes), mobile curation, critical soundmapping, and sensory ethnography. Check out Milena’s Story Map, “Soundscapes of Productivity” about coffee shop soundscapes as the office ambience of the creative economy freelance workers.

Milena is a former board member of the International Community on Auditory Displays, an alumni of the Institute for Research on Digital Learning at York University, and former Research Think-Tank and Academic Advisor in learning innovation for the social enterprise InWithForward. More recently, Milena serves on the board for the Hush City Mobile Project founded by Dr. Antonella Radicchi, as well as WISWOS, founded by Dr. Linda O Keeffe.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“One Scream is All it Takes: Voice Activated Personal Safety, Audio Surveillance, and Gender Violence“—María Edurne Zuazu

Gendered Sonic Violence, from the Waiting Room to the Locker Room–Rebecca Lentjes

SO! Amplifies: Mendi+Keith Obadike and Sounding Race in America

detritus 1 & 2 and V.F(i)n_1&2 : The Sounds and Images of Postnational Violence in Mexico–Luz María Sánchez

Hearing Eugenics—Vibrant Lives

SO! Podcast #79: Behind the Podcast: deconstructing scenes from AFRI0550, African American Health Activism

Welcome to Next Gen sound studies! In the month of November, you will be treated to the future. . . today! In this series, we will share excellent work from undergraduates, along with the pedagogy that inspired them. You’ll read voice biographies (Kaitlyn Liu’s “My Voice, or On Not Staying Quiet,”) check out blog assignments (David Lee’s “Mukbang Cooks, Chews, and Heals”), listen to podcasts, and read detailed histories that will inspire and invigorate. Bet. –JS

We are thrilled to bring you today’s utter gift from Dr. Nic John Ramos (Drexel University) and Laura Garbes (Brown University) who team taught this tremendous course in the Department of Africana Studies at Brown University called African American Health Activism from Colonialism to AIDS that used podcasting as a critical venue of knowledge production and a pedagogical tool. The introductory paragraph of their syllabus explains the class as follows:

Welcome to Next Gen sound studies! In the month of November, you will be treated to the future. . . today! In this series, we will share excellent work from undergraduates, along with the pedagogy that inspired them. You’ll read voice biographies (Kaitlyn Liu’s “My Voice, or On Not Staying Quiet,”) check out blog assignments (David Lee’s “Mukbang Cooks, Chews, and Heals”), listen to podcasts, and read detailed histories that will inspire and invigorate. Bet. –JS

We are thrilled to bring you today’s utter gift from Dr. Nic John Ramos (Drexel University) and Laura Garbes (Brown University) who team taught this tremendous course in the Department of Africana Studies at Brown University called African American Health Activism from Colonialism to AIDS that used podcasting as a critical venue of knowledge production and a pedagogical tool. The introductory paragraph of their syllabus explains the class as follows:

In other words– theirs wasn’t a radio or a podcasting themed course, but instead, Professors Ramos and Garbes introduced podcasting to students as a mode of critical thought and expression. As they reflect:This historical survey course examines African American activism and social movements from Colonialism and Emancipation to the contemporary period through the lens of African American access to health resources. The course also explores how marginalized peoples and communities are using new digital technologies, such as podcasting, to represent and intervene on historical inequalities. Thus, the course aims to produce public historians who are well versed in the history of medicine from the perspective of African descended peoples AND can produce social justice-oriented digital content based on their knowledge of history and marginalized communities.

Like many educators, we see podcasting as an opportunity to enter students on the ground floor of an increasingly popular social medium that many conceive of as a potentially more democratic sound space. We firmly believe spaces of sound, such as podcasting, however, cannot truly be democratic unless more people have the knowledge and know-how to enter their voices and the voices of their communities into the fray. In these troubling times, we especially see podcasting as an opportunity to share and tell stories often misheard, untold, and unheard in history and on the radio. It was important to us that our students recognize that the voices of the communities they come from and/or the histories rarely hear elsewhere have a legitimate place in the academy and on the airwaves.Today, via the form of a podcast, Ramos and Garbes go fantastically meta- on us, introducing one of the final projects from their course–an audio story entitled “Shadows in Harriet’s Dawn” by Brown Undergraduates Mali Dandridge, Sterling Stiger, and Amber Parson— giving us rare insight and commentary on the process. The student work understands Harriet Jacobs (activist and author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl) in the context of enslavement and childhood trauma. The full transcript of their “Behind the Podcast” podcast follows this introduction. Here’s the students’ podcast description:

Through the re-telling of American author and former slave Harriet Jacobs’s girlhood from her autobiography Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl there is an opportunity to learn about the adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) of children of American slavery. Harriet’s 19th-century trials of navigating complicated family dynamics, emotional abuse, and sexual harassment at a young age are analyzed in the lens of the modern science supporting the clinical ACEs questionnaire tool. This podcast will hopefully mark the beginning of creating more discussions that uncover the social determinants of well-being and trauma in a way that could be helpful even for the struggles of modern day youth.You may also download the syllabus for their course (African American Health Activism Syllabus 1.25.2018 ), along with their Podcast Pitching Assignment (AFRI 0550 Pitching Assignment for Webpage), a process assignment they named the “fieldwork summary prompt” (AFRI0550 Fieldwork Summary Prompt), and the grading rubric for this assignment (AFRI0550 Podcast Grading Rubric). In addition, Ramos and Garbes have also generously documented this experience via their collaborative website: Case Study: Afri 0550, A PEDAGOGICAL APPROACH TO STORYTELLING AND TECHNOLOGY that you absolutely MUST check out. We all have so much to learn! CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD: SO! Podcast 79: Behind the Podcast: deconstructing scenes from AFRI0550, African American Health Activism SUBSCRIBE TO THE SERIES VIA APPLE PODCASTS FOR TRANSCRIPT: SCROLL BELOW or ACCESS EPISODE THROUGH APPLE PODCASTS , locate the episode and click on the three dots to the far right. Click on “view transcript.”

Behind the Podcast: deconstructing scenes from AFRI0550, African American Health Activism In this podcast, Dr. Nic John Ramos and Laura Garbes introduce Shadows in Harriet’s Dawn, a final audio project by Mali Dandridge, Sterling Stiger, and Amber Parson. They analyze the project in the context of the course, African American Health Activism, taught at Brown University in spring 2019. The two reflect on how beginner technical and ethical training come together within in the audio story. Resources mentioned within this podcast provided at the end of this transcript. Listeners are highly encouraged to listen to this as a piece of the larger course blog, written by Laura and Nic, and developed as a webpage by Leo Selvaggio, Instructional Media Specialist at the Brown MML. Nic Ramos: Hi, this is Nic John Ramos. Laura Garbes: Hi, this is Laura Garbes, NR: and this is, Behind the Podcast… LG: …deconstructing scenes from African American Health Activism. NR: Laura, what are we doing in this podcast? LG: Right, So first of all, we’re trying to display a really awesome audio story that our students made. That’s first and foremost. But we’re also using it as a teaching tool, right? NR: Yeah, that’s right. For our class called African American Health Activism from Colonialism to AIDS, which is taught in the Department of Africana Studies here at Brown University. This historical survey course examines African American activism and social movements from colonialism and emancipation to the contemporary period, through the lens of African American access to health resources. The course also explores how marginalized people and communities are using new digital technologies such as podcasting to represent and intervene on historical inequalities. The course aims to produce public historians who are well versed in the history of medicine from the perspective of African-descended peoples and can produce social justice oriented digital content based on their knowledge of history and marginalized communities. LG: Yeah. So part of this is really giving space to show the great work on this audio story on Harriet Jacobs and childhood trauma. Through doing so, we want to touch on a few things behind the process that will be good for educators looking to implement similar projects in their own classrooms. NR: If you’re interested in learning more about podcasting as a pedagogical tool, check out our webpage. LG: Well, check out our webpage, which will put it in the show notes later. Always with the show notes.. [laughs] Right, because there were going to put in a bunch of sound clips of this and sort of a step by step guide of how to replicate the process assigning a podcast. And, you know, there are other sources out there and we linked them at the end of that guide. But what we really wanted to emphasize was like… Okay, cool there is a lot of stuff on the technical recording and the technical interviewing pieces. And then there’s some scholarship, notably Dr. Jenny Lynn Stoever on the sonic color line, and the cultural politics of listening and how our listening ear has been conditioned. We weren’t really finding something that kind of weaves those two together, and we really think it’s important that when we’re teaching the technique, it not be divorced from that theory. NR: The podcast we’re showcasing today is called Shadows in Harriet’s Dawn, on the childhood trauma of American slavery, through the retelling of American author and former slave Harriet Jacobs’ girlhood from her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. There’s this opportunity that our students saw to learn about the adverse childhood experiences of children of American slavery. This podcast will hopefully mark the beginning of creating more discussions that uncover the social determinants of well-being and trauma in a way that could be helpful even for the struggles of modern-day youth. LG: Yes, okay, so this podcast was created by three students in your class. Amber, Sterling and Molly. So, let’s take a listen. Upbeat, childlike music Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl Archive #1: I was born a slave; but I never knew it till six years of happy childhood had passed away. (Chapter I) Children’s music box mixed in with the sound of children laughing Archive #1: My father was a carpenter, and considered so intelligent and skilful in his trade, that, when buildings out of the common line were to be erected, he was sent for from long distances, to be head workman. On condition of paying his mistress two hundred dollars a year, and supporting himself, he was allowed to work at his trade, and manage his own affairs. His strongest wish was to purchase his children; but, though he several times offered his hard earnings for that purpose, he never succeeded. In complexion my parents were a light shade of brownish yellow, and were termed mulattoes. They lived together in a comfortable home; and, though we were all slaves, I was so fondly shielded that I never dreamed I was a piece of merchandise, trusted to them for safe keeping, and liable to be demanded of them at any moment. (Chapter I) Loud thump Silence Mali: But, almost inevitably, the fond shielding around Harriet would cease to exist, profoundly changing her life for the worse. Sterling: For Harriet, the context in which that happy childhood took place would be revealed to be one filled with abuse and trauma. Amber: Trauma works to stay hidden and unexposed. It knows how and when to enter into the crawl space, and it is always on the run to move from generation to generation. Amber: My name is Amber and I am here alongside my other fellow classmates Pauses Sterling: Hello, I’m Sterling. Pauses Mali: Hi, I’m Mali. Amber: And we’re here today to explore Harriet Jacobs’ story in relation to childhood trauma. LG: Ok Nic. I’m going to stop this right here, just to say two and a half minutes have passed. That’s it. And there’s already a collection here of kind of really rich sound clips. You hear from the archive an approximation of Harriet Jacobs’s voice straight from the very beginning. You hear different types of music. You hear their own voices that have to be cut out of different sound clips. It’s already getting pretty complex. And as we’ll kind of see as we go into it, they’ll go on to cut in all of the interviewees’ voices and introductions so that you’ve got a sort of sense of where we’re going. NR: Yeah, what I really love about this is that they’ve really set the tone and mood, but also have given us a clue about where they want to take this podcast, what direction they want to take this podcast. What I really love about this is that we get already a very historical context, that they’re drawing out how they want to connect it to really present-day issues. LG: And I think two things really made those possible. So first is the fact that we have trainings at the MML at Brown, which in that digital resource guide we mentioned there’s the stuff that is going to be available on arranging tracks. When you specifically focus on arranging tracks, it makes it possible for first-time podcasters to think a little bit more creatively instead of saying: we’re going to put the entire chunk of what we recorded from person A, the entire chunk from person B, and we’ll do our analysis in the end. You can see that they’re being creative. They’re interspersing these things like quotes in an academic essay or a historical essay. NR: Yeah. What I love is that we’re going to hear in the next couple minutes all the people that they’re going to interview as experts to craft an argument and perspective on Harriet Jacobs. LG: Let’s listen. Sterling: Through the re-telling of this American author and former slave’s girlhood from her autobiography Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, there is an opportunity to learn about the adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, of children in American slavery. Mali: Harriet’s 19th-century trials of navigating slavery, complicated family dynamics, emotional abuse, and sexual harassment at a young age have a lot to reveal about trauma and the different ways it is able to manifest itself. We hope to offer both a lens of social and scientific understanding of these complexities using knowledge from the following expert sources, starting with our guest Anna Thomas. Cheeky, academic music Enter: Montage of guest speakers Anna: I am a PhD candidate in the English Department at Brown. I am graduating this year, and I work on African American literature alongside Caribbean literature. I study the relationship between ethics and form in nineteenth and twentieth century African and Caribbean literature. Ramos: I’m Nic John Ramos I’m the Mellon postdoctoral fellow in Race and Science and Medicine at Brown University. Dima: My name is Dima Amso, and I am a professor in the Cognitive Linguistic and Psychological Sciences Department. I study brain and cognitive development. Kevin: My name is Kevin Bath. I am a professor in Cognitive Linguistic and Psychological Sciences. My research focuses on using animal models to understand how real life adversity, especially during early post-neonatal, impact the development of the brain and may drive risk for negative outcomes. Amber: Through the collective perspectives of us, our guests, and several archival sources, we now present to you the story of Harriet…that is a story that beautifully and remarkably demonstrates resilience towards the mobility of trauma. 19th century music Archive #1: When I was six years old, my mother died; and then, for the first time, I learned, by the talk around me, that I was a slave. My mother’s mistress was the daughter of my grandmother’s mistress. She was the foster sister of my mother; they were both nourished at my grandmother’s breast. In fact, my mother had been weaned at three months old, that the babe of the mistress might obtain sufficient food. They played together as children; and, when they became women, my mother was a most faithful servant to her whiter foster sister. On her death-bed her mistress promised that her children should never suffer for anything; and during her lifetime she kept her word. They all spoke kindly of my dead mother, who had been a slave merely in name, but in nature was noble and womanly. I grieved for her, and my young mind was troubled with the thought who would now take care of me and my little brother. I was told that my home was now to be with her mistress; and I found it a happy one. No toilsome or disagreeable duties were imposed upon me. My mistress was so kind to me that I was always glad to do her bidding, and proud to labor for her as much as my young years would permit. (Chapter I) I would sit by her side for hours, sewing diligently, with a heart as free from care as that of any free-born white child. When she thought I was tired, she would send me out to run and jump; and away I bounded, to gather berries or flowers to decorate her room. Those were happy days—too happy to last. (Chapter I) The slave child had no thought for the morrow; but there came that blight, which too surely waits on every human being born to be a chattel. (Chapter I) Science music Dima: So, in general, some basic principles of brain development are that there’s tremendous amounts of change that happens very early on in postnatal life. So after like about three or four, the brain is sort of fine-tuning rather than showing huge amounts of organization. Even still, the way that the brain develops is that continually tries to adapt to its environment so both positive experiences are highly shaping and negative experiences are highly shaping, um and stress in particular has received a lot of attention in the developmental science community, both with respect to human stressors and animal models that try to recapitulate those and try to understand what’s under the hood so to speak and the idea is that what’s happening with stress and trauma especially early on in postnatal life is that it’s um shaping the system and ways that then get sort of set that sort of set up their brains to have long-term consequences of that stressor. NR: So that was Dima Amso, one of the interviewees of this podcast. And what I like what the students are doing here is that they’re setting up an expert voice to provide context to what we just heard and we’re going to hear in the future. But as you can tell, they’re going to set up these experts in a way in which they’re able to speak for themselves, and the listener is going to be able to hopefully differentiate the different positions that some experts say without them having to directly say the differences between these experts… if that makes sense. LG: Yeah, this was a conversation we had in that Q&A discussion. We went in and we talked through techniques with the students. But then we moved on to OK, actually, you’ll have to do a little field work log and then we’ll talk again, because there’s only so much you can do before you actually go out there and interview. So I think what was great was building in time to actually discuss the interviews, because there were a few instances and a few groups were saying, OK, there some discrepancies here between either different interviewees’ perspectives. Or there were discrepancies between the interviewees’ perspectives and perhaps the main argument trying to be made. Allowing for those differences to kind of breathe, while weaving a cohesive narrative that’s fit for a podcast, is an art, and they sort of have to walk this tightrope. And that was definitely one of the skills of argumentation that could definitely be transferred over for them when they’re writing essays in the future. NR: You know, the students had to edit, and they had to figure out what story they wanted to tell You can tell that some of these experts are giving a story that conflate animal studies with human behavior in a way that’s really popular in making comparisons today within science. But the students also had to make a decision about whether or not they wanted to go down the road of talking about the history of scientific racism and the conflation of some humans as animals. And while there’s room here is that I know that they had a lot of work to do around just talking about Harriet’s story alone. You’ll find later that they’ve just left some of these opportunities to delve deeper, where it’s on the listener to think about, make their own conclusions about that. Let me say a note on ethical interviewing is that when we say ethical interviewing, we’re allowing the experts to speak on their terms. And allowing them, allowing their positions and their thoughts to manifest through the other voices that you’re going to hear right? In the contrast of the comparisons that listeners are going to be able to hear in the different voices and positions they take. LG: Right and coming up next, as we’ll see, they definitely contextualize all of the different interviewees’ comments, like Sterling here. Sterling: According to Harriet from her narrative, she had an early childhood with “unusually fortunate circumstances” in comparison to other children of American slavery. Mali: This understanding of her background is important to truly capture understanding of how events that would impact her later in life would vastly change herself perception regarding her quality of life. In particular, these events would occur after the death of her described “kind mistress” when the mistress’s sister and new husband Dr. Flint claimed ownership of Harriet. Dima: You know, childhood development isn’t happening in a vacuum, it’s happening in a broader context and a good part of early child development is about the caregiving, no matter how. It’s really interesting to think about the animal models. I do these examples, so we study socioeconomic status in a lab and what they try to do is recapitulate what happens when a great parent gets their resources taken away, so for animals and the mouse studies, you can take away the bedding and make it really hard for them to keep their babies warm and they are just like working so hard to replace that to take care of that and that then stresses them out, which turns out to have consequences on the growing pup later, and then if you add an additional stressor you kind of see how this sort of balloons into multiple now stressors and formative times. Loud thump Archive #1: During the first years of my service in Dr. Flint’s family, I was accustomed to share some indulgences with the children of my mistress. Though this seemed to me no more than right, I was grateful for it, and tried to merit the kindness by the faithful discharge of my duties. (Chapter V) Sound: opening of door…. assertive, domineering footsteps… heartbeat But I now entered on my fifteenth year—a sad epoch in the life of a slave girl. My master began to whisper foul words in my ear. (Chapter V) Enter old, southern man whispering LG: So something I’m hearing here that is fantastic are the sound effects: something to keep our interest, that loud thump you hear before you hear Harriet Jacobs’s voice again. NR: Just this science music they used… LG: It’s so on point, right? NR: Yeah, the science music, the loud thump, opening the door, footsteps, heartbeat, they’re really layering a lot of stuff to keep the listener interested, and many people wouldn’t think about doing that. You could imagine that if they didn’t have these elements in here, you would just be hearing one long monologue, that quite frankly you’d be just bored.

Figure 1: Final Audition Software File for “Shadows in Harriet’s Dawn”

- “P-Pops And Other Plosives.” Transom, April 27, 2016. https://transom.org/2016/p-pops-plosives/.

- Workshop I: Intro to Audio Editing Multimedia Lab at Brown. https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1xNoz4xO50AYJyEahLLuAOXx_TfPWdP_iBke7j7jTXcI/edit?usp=sharing

- AFRI0550: Hearing a Story Structure https://drive.google.com/file/d/10F0EcgIApO1Nw0W3ZB4edFliWroR31bA/view?usp=sharing

Nic John Ramos is an Assistant Professor in the Department of History at Drexel University and held a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellowship of Race in Medicine and Science at Brown University from 2017-2019. His article “Poor Influences and Criminal Locations: Los Angeles’s Skid Row, Multicultural Identities, and Normal Homosexuality” was recently published in American Quarterly.

Laura Garbes is a PhD student in sociology at Brown University, where she studies racism, whiteness, and cultural organizations. Her research explores the racialization of sound in public broadcasting. She is also a fellow at Brown University’s Swearer Center for Public Service, and a member of the Du Boisian Scholar Network. — REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

SO! Podcast #78: Ethical Storytelling in Podcasting

A Manifesto, or Sounding Out!’s 51st Podcast!!! – Aaron Trammell

Deep Listening as Philogynoir: Playlists, Black Girl Idiom, and Love–Shakira Holt

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

SO! Podcast #78: Ethical Storytelling in Podcasting

A Manifesto, or Sounding Out!’s 51st Podcast!!! – Aaron Trammell

Deep Listening as Philogynoir: Playlists, Black Girl Idiom, and Love–Shakira Holt ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- SO! Reads: Alexis McGee’s From Blues To Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics

- SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

- Impaulsive: Bro-casting Trump, Part I

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments