Your Voice is (Not) Your Passport

In summer 2021, sound artist, engineer, musician, and educator Johann Diedrick convened a panel at the intersection of racial bias, listening, and AI technology at Pioneerworks in Brooklyn, NY. Diedrick, 2021 Mozilla Creative Media award recipient and creator of such works as Dark Matters, is currently working on identifying the origins of racial bias in voice interface systems. Dark Matters, according to Squeaky Wheel, “exposes the absence of Black speech in the datasets used to train voice interface systems in consumer artificial intelligence products such as Alexa and Siri. Utilizing 3D modeling, sound, and storytelling, the project challenges our communities to grapple with racism and inequity through speech and the spoken word, and how AI systems underserve Black communities.” And now, he’s working with SO! as guest editor for this series (along with ed-in-chief JS!). It kicked off with Amina Abbas-Nazari’s post, helping us to understand how Speech AI systems operate from a very limiting set of assumptions about the human voice. Last week, Golden Owens took a deep historical dive into the racialized sound of servitude in America and how this impacts Intelligent Virtual Assistants. Today, Michelle Pfeifer explores how some nations are attempting to draw sonic borders, despite the fact that voices are not passports.–JS

—

In the 1992 Hollywood film Sneakers, depicting a group of hackers led by Robert Redford performing a heist, one of the central security architectures the group needs to get around is a voice verification system. A computer screen asks for verification by voice and Robert Redford uses a “faked” tape recording that says “Hi, my name is Werner Brandes. My voice is my passport. Verify me.” The hack is successful and Redford can pass through the securely locked door to continue the heist. Looking back at the scene today it is a striking early representation of the phenomenon we now call a “deep fake” but also, to get directly at the topic of this post, the utter ubiquity of voice ID for security purposes in this 30-year-old imagined future.

In 2018, The Intercept reported that Amazon filed a patent to analyze and recognize user’s accents to determine their ethnic origin, raising suspicion that this data could be accessed and used by police and immigration enforcement. While Amazon seemed most interested in using voice data for targeting users for discriminatory advertising, the jump to increasing surveillance seemed frighteningly close, especially because people’s affective and emotional states are already being used for the development of voice profiling and voice prints that expand surveillance and discrimination. For example, voice prints of incarcerated people are collected and extracted to build databases of calls that include the voices of people on the other end of the line.

“Collect Calls From Prison” by Flickr User Cobalt123 (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

What strikes me most about these vocal identification and recognition technologies is how their appeal seems to lie, for advertisers, surveillers, and policers alike that voice is an attractive method to access someone’s identity. Supposedly there are less possibilities to evade or obfuscate identification when it is performed via the voice. It “is seen as a solution that makes it nearly impossible for people to hide their feelings or evade their identities.” The voice here works as an identification document, as a passport. While passports can be lost or forged, accent supposedly gives access to the identity of a person that is innate, unchanging, and tied to the body. But passports are not only identification documents. They are also media of mobility, globally unequally distributed, that allow or inhibit movement across borders. States want to know who crosses their borders, who enters and leaves their territory, increasingly so in the name of security.

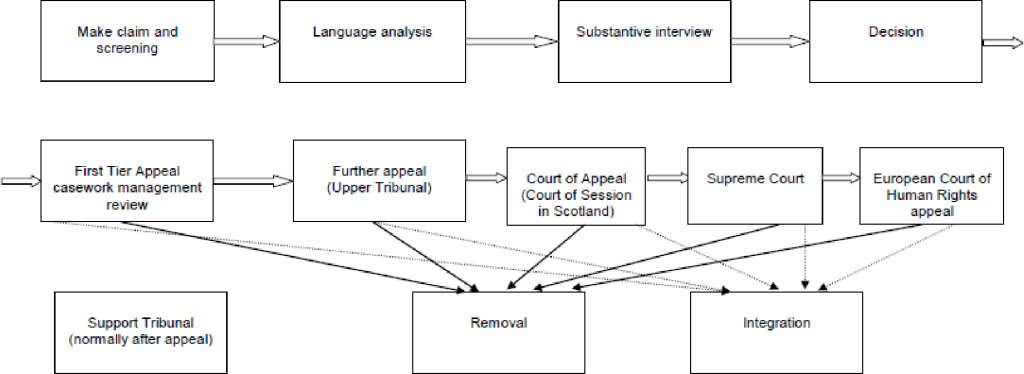

What, then, when the voice becomes a passport? Voice recognition systems used in asylum administration in the Global North show what is at stake when the voice, and more specifically language and dialect, come to stand in for a person’s official national identity. Several states including Denmark, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Sweden, as well as Australia and Canada have been experimenting with establishing the voice, or more precisely language and dialect, to take on the passport’s role of identifying and excluding people.

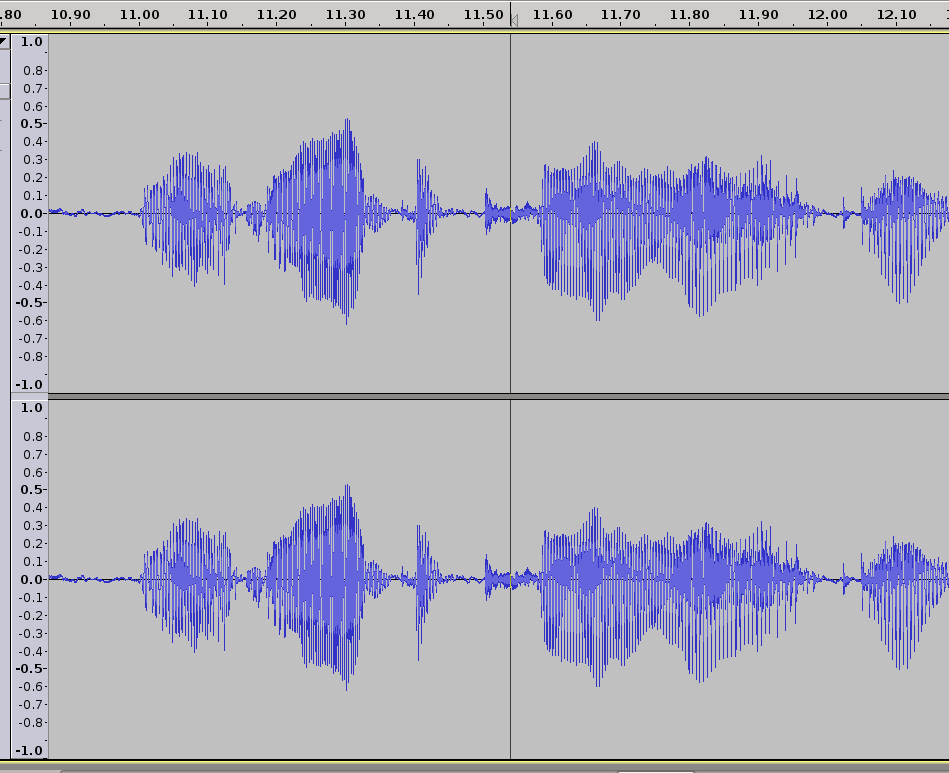

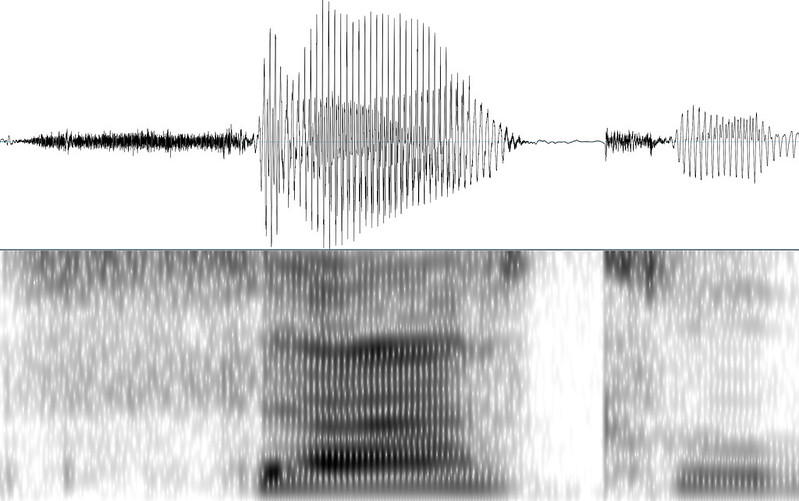

In the 1990s—not too far from the time of Sneakers release—they started to use a crude form of linguistic analysis, later termed Language Analysis for the Determination of Origin (LADO), as part of the administration of claims to asylum. In cases where people could not provide a form of identity documentation or when those documents would be considered fraudulent or inauthentic, caseworkers would look for this national identity in the languages and dialects of people. LADO analyzes acoustic and phonetic features of recorded speech samples in relation to phonetics, morphology, syntax, and lexicon, as well as intonation and pronunciation.

The problems and assumptions of this linguistic analysis are multiple as pointed out and critiqued by linguists. 1) it falsely ties language to territorial and geopolitical boundaries and assumes that language is intimately tied to a place of origin according to a language ideology that maps linguistic boundaries onto geographical boundaries. Nation-state borders on the African continent and in the Middle East were drawn by colonial powers without considerations of linguistic communities. 2) LADO thinks of language and dialect as static, monoglossic and a stable index of identity. These assumptions produce the idea of a linguistic passport in which language is supposed to function as a form of official state identification that distributes possibilities and impossibilities of movement and mobility. As a result, the voice becomes a passport and it simultaneously functions as a border, by inscribing language into territoriality. As Lawrence Abu Hamdan has written and shown through his sound art work The Freedom of Speech itself, LADO functions to control territory, produce national space, and attempts to establish a correlation between voice and citizenship.

I’ll add that the very idea of a passport has a history rooted in forms of colonial governance and population control and the modern nation-state and territorial borders. The body is intimately tied to the history of passports and biometrics. For example, German colonial administrators in South-West Africa, present day Namibia, and German overseas colony from 1884 to 1919 instituted a pass batch system to control the mobility of Indigenous people, create an exploitable labor force, and institute and reinforce white supremacy and colonial exploitation. Media and Black Studies scholar Simone Browne describes biometrics as “digital epidermalization,” to describe how surveillance becomes inscribed and encoded on the skin. Now, it’s coming for the voice too.

In 2016 the German government took LADO a step further and started to use what they call a voice biometric software that supposedly identifies the place of origin of people who are seeking asylum. Someone’s spoken dialect is supposedly recognized and verified on the basis of speech recordings with an average lengths of 25,7 seconds by a software employed by the German Ministry for Migration and Refugees (in German abbreviated as BAMF). The now used dialect recognition software used by German asylum administrators distinguishes between 4 large Arabic dialect groups: Levantine, Maghreb, Iraqi, Egyptian, and Gulf dialect. Just recently this was expanded with language models for Farsi, Dari and Pashto. There are plans to expand this software usage to other European countries, evidenced by BAMF traveling to other countries to demonstrate their software.

This “branding” of BAMF’s software stands in stark contradiction to its functionality. The software’s error rate is 20 percent. It is based on a speech sample as short as 26 seconds. People are asked to describe pictures while their speech is recorded, the software then indicates a percentage of probability of the spoken dialect and produces a score sheet that could indicate the following: 74% Egyptian, 13% Levantine, 8% Gulf Arabic, 5 % Other. The interpretation of results is left to the caseworkers without clear instructions on how to weigh those percentages against each other. The discretion left to caseworkers makes it more difficult to appeal asylum decisions. According to the Ministry, the results are supposed to give indications and clues about someone’s origin and are not a decision-making tool. However, as I have argued elsewhere, algorithmic or so-called “intelligent” bordering practices assume neutrality and objectivity and thereby conceal forms of discrimination embedded in technologies. In the case of dialect recognition the score sheet’s indicated probabilities produce a seeming objectivity that might sway case-workers in one direction or another. Moreover, the software encodes distinctions between who is deserving of protection and who is not; a feature of asylum and refugee protection regimes critiqued by many working in the field.

The functionality and operations of the software are also intentionally obscured. Research and sound artist Pedro Oliveira addresses the many black-boxed assumptions entering the dialect recognition technology. For instance, in his work Das hätte nicht passieren dürfen he engages with the labor involved in producing sound archives and speech corpora and challenges “ the idea that it might be feasible, for the purposes of biometric assessment, to divorce a sound’s materiality from its constitution as a cultural phenomenon.” Oliveira’s work counters the lack of transparency and accountability of the BAMF software. Information about its functionality is scarce. Freedom of information requests and parliamentary inquiries about the technical and algorithmic properties and training data of the software were denied as the information was classified because “the information can be used to prepare conscious acts of deception in the asylum proceeding and misuse language recognition for manipulation,” the German government argued. While it is not necessarily deepfakes like the one Brandes produced to forego a security system that the German authorities are worried about, the specter of manipulation of the software looms large.

The consequences of the software’s poor functionality can have drastic consequences for asylum decisions. Vice reported in 2018 the story of Hajar, whose name was changed to protect his identity. Hajar’s asylum application in Germany was denied on the basis of a dialect recognition software that supposedly indicated that he was a Turkish speaker and, thus, could not be from the Autonomous Region Kurdistan as he claimed. Hajar who speaks the Kurdish dialect Sorani had been instructed by BAMF to speak into a telephone receiver and describe an image in his first language. The software’s results indicated a 63% probability that Hajar speaks Turkish and the caseworker concluded that Hajar had lied in his asylum hearings about his origin and his reasons to seek asylum in Germany who continued to appeal the asylum decision. The software is not equipped to verify Sorani and should not have been used on Hajar in the first place.

Why the voice? It seems that bureaucrats and caseworkers saw it as a way to identify people with ease and scale language analysis more easily. It is also important to consider the context in which this so-called voice biometry is used. Many people who seek asylum in Germany cannot provide identity documents like passports, birth certificates, or identification cards. This is the case because people cannot take them with them as they flee, they are lost or stolen on people’s journeys, or they are confiscated by traffickers. Many forms of documentation are also not accepted as legitimate by state authorities. Generally, language analysis is used in a hostile political context in which claims to asylum are increasingly treated with suspicion.

The voice as a part of the body was supposed to provide an answer to this administrative problem of states. In response to the long summer of migration in 2015 Germany hired McKinsey to overhaul their administrative processes, save money, accelerate asylum procedures, and make them more “efficient.” In July 2017, the head of the Department for Infrastructure and Information Technology of the German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees hailed the office’s new voice and dialect recognition software as “unrivaled world-wide” in its capacity to determine the region of origin of asylum seekers and to “detect inconsistencies” in narratives about their need for protection. More than identification documents, personal narratives, or other features of the body, the voice, the BAMF expert suggests is the medium that allows for the indisputable verification of migrants’ claims to asylum, ostensibly pinpointing their place of origin.

Voice and dialect recognition technology are established by policy makers and security industries as particularly successful tools to produce authentic evidence about the origin of asylum seekers. Asylum seekers have to sound like being from a region that warrants their claims to asylum: requiring the translation of voices into geographical locations. As a result, automated dialect recognition becomes more valuable than someone’s testimony. In other words, the voice, abstracted into a percentage, becomes the testimony. Here, the software, similarly to other biometric security systems, is framed as more objective, neutral, and efficient way of identifying the country of origin of people as compared to human decision-makers. As the German Migration agency argued in 2017: “The IT supported, automated voice biometric analysis provides an independent, objective and large-scale method for the verification of the indicated origin.”

The use of dialect recognition puts forth an understanding of the voice and language that pinpoints someone’s origin to a certain place, without a doubt and without considering how someone’s movement or history. In this sense, the software inscribes a vision of a sedentary, ahistorical, static, fixed, and abstracted human into its operations. As a result, geographical borders become reinforced and policed as fixed boundaries of territorial sovereignty. This vision of the voice ignores multiple mobilities and (post)colonial histories and reinscribes the borders of nation-states that reproduce racial violence globally. Dialect recognition reproduces precarity for people seeking asylum. As I have shown elsewhere, in the absence of other forms of identification and the presence of generalized suspicion of asylum claims, accent accumulates value while the content of testimony becomes devalued. Asylum applicants are placed in a double bind, simultaneously being incited to speak during asylum procedures and having their testimony scrutinized and placed under general suspicion.

Similar to conventional passports, the linguistic passport also represents a structurally unequal and discriminatory regime that needs to be abolished. The software was framed as providing a technical solution to a political problem that intensifies the violence of borders. We need to shift to pose other questions as well. What do we want to listen to? How could we listen differently? How could we build a world in which nation-states and passports are abolished and the voice is not a passport but can be appreciated in its multiplicity, heteroglossia, and malleability? How do we want to live together on a planet increasingly becoming uninhabitable?

—

Featured Image: Voice Print Sample–Image from US NIST

—

Michelle Pfeifer is postdoctoral fellow in Artificial Intelligence, Emerging Technologies, and Social Change at Technische Universität Dresden in the Chair of Digital Cultures and Societal Change. Their research is located at the intersections of (digital) media technology, migration and border studies, and gender and sexuality studies and explores the role of media technology in the production of legal and political knowledge amidst struggles over mobility and movement(s) in postcolonial Europe. Michelle is writing a book titled Data on the Move Voice, Algorithms, and Asylum in Digital Borderlands that analyses how state classifications of race, origin, and population are reformulated through the digital policing of constant global displacement.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“Hey Google, Talk Like Issa”: Black Voiced Digital Assistants and the Reshaping of Racial Labor–Golden Owens

Beyond the Every Day: Vocal Potential in AI Mediated Communication –Amina Abbas-Nazari

Voice as Ecology: Voice Donation, Materiality, Identity–Steph Ceraso

The Sound of What Becomes Possible: Language Politics and Jesse Chun’s 술래 SULLAE (2020)—Casey Mecija

The Sonic Roots of Surveillance Society: Intimacy, Mobility, and Radio–Kathleen Battles

Acousmatic Surveillance and Big Data–Robin James

“Hey Google, Talk Like Issa”: Black Voiced Digital Assistants and the Reshaping of Racial Labor

.

In summer 2021, sound artist, engineer, musician, and educator Johann Diedrick convened a panel at the intersection of racial bias, listening, and AI technology at Pioneerworks in Brooklyn, NY. Diedrick, 2021 Mozilla Creative Media award recipient and creator of such works as Dark Matters, is currently working on identifying the origins of racial bias in voice interface systems. Dark Matters, according to Squeaky Wheel, “exposes the absence of Black speech in the datasets used to train voice interface systems in consumer artificial intelligence products such as Alexa and Siri. Utilizing 3D modeling, sound, and storytelling, the project challenges our communities to grapple with racism and inequity through speech and the spoken word, and how AI systems underserve Black communities.” And now, he’s working with SO! as guest editor for this series (along with ed-in-chief JS!). It kicked off with Amina Abbas-Nazari’s post, helping us to understand how Speech AI systems operate from a very limiting set of assumptions about the human voice. Today Golden Owens explored what happens when companies sell Black voices along with their Intelligent Virtual Assistants. Tune in for a deep historical dive into the racialized sound of servitude in America. Even though corporations aren’t trying to hear this absolutely critical information–or Black users in general–they better listen up. –JS

—

In October 2019, Google released an ad for their Google Assistant (GA), an intelligent virtual assistant (IVA) that initially debuted in 2016. As revealed by onscreen text and the video’s caption, the ad’s announced that the GA would soon have a new celebrity voice. The ten-second promotion includes a soundbite from this unseen celebrity—who states: “You can still call me your Google Assistant. Now I just sound extra fly”— followed by audio of the speaker’s laughter, a white screen, the GA logo, and a written question: “Can you guess who it is?”

Consumers quickly speculated about the person behind the voice, with many posting their guesses on Reddit. The earliest comments named Tiffany Haddish, Lizzo, and Issa Rae as prospects, with other users affirming these guesses. These women were considered the most popular contenders: two articles written about the new GA voice cited the Reddit post, with one calling these women Redditors’ most popular guesses and the other naming only them as users’ desired choices. Those who guessed Rae were proven correct. One day after the ad, Google released a longer promo revealing her as the GA’s new voice, including footage of Rae recording responses for the assistant. The ad ends with Rae repeating the “extra fly” line from the initial promo, smiling into the camera.

Google’s addition of Rae as an IVA voice option is one of several recent examples of Black people’s voices employed in this manner. Importantly, this trend toward Black-voiced IVAs deviates from the pre-established standard of these digital aides. While there are many voice options available, the default voices for IVAs are white female voices with flat dialects. This shift toward Black American voices is notable not only because of conversations about inclusion—with some Black users saying they feel more represented by these new voices—but because this influx of Black voices marks a spiritual return to the historical employment of Black people as service-providing, labor-performing entities in the United States, thus subliminally reinforcing historical biases about Black people as uniquely suited for performing this type of work.

Marketed as labor-saving devices, IVAs are programmed to assist with cooking and grocery shopping, transmit messages and reminders, and provide entertainment, among other tasks. Since the late 2010s they have also been able to operate other technologies within users’ homes: Alexa, for example, can control Roomba robotic vacuums; IVA-compatible smart plugs or smart home devices enable IVAs to control lights, locks, thermostats, and other such apparatuses. Behaviorally, IVAs are designed and expected to be on-call at all times, but not to speak or act out of turn—with programmers often directed to ensure these aides are relatable, reliable, trustworthy, and unobtrusive.

Far from operating in a vacuum, IVAs eerily evoke the presence of and parameters set for enslaved workers and domestic servants in the U.S.—many of whom have historically been Black American women. Like IVAs, Black women servants cooked, cleaned, entertained children, and otherwise served their (predominantly white) employers, themselves operating as labor-saving devices through their performance of these labors. Employers similarly expected these women to be ever-available, occupy specific areas of the home, and obey all requests and demands—and were unsettled if not infuriated when maids did not behave according to their expectations.

White women being the default voices of IVAs has somewhat obfuscated the degree to which these aides have re-embodied and replaced the Black servants who once predominantly executed this work, but incorporating Black voices into these roles removes this veil, symbolically re-implementing Black people as labor-performing entities by having them operate as the virtual assistants who now perform much of the labor Black workers historically performed. Enabling Black people to be used as IVAs thus re-aligns Black beings with the performance of service and labor.

While Black women were far from the only demographic conscripted into domestic labor, by the 1920s they comprised a “permanent pool of servants” throughout the country, due largely to the egress of white American and immigrant women from domestic service into fields that excluded Black women (183). Black women’s prominence in domestic service was heavily reflected in early U.S. media, which overwhelmingly portrayed domestic servants not just as Black women, but as Black Mammies—domestic servant archetypes originally created to promote the myth that Black women “were contented, even happy as slaves.” Characters like Gone with the Wind’s “Mammy” pulled both from then-current associations of Black women with domestic labor and from white nostalgia for the Antebellum era, and specifically for the archetypal Mammy—marking Black women as idealized labor-performing domestics operating in service of white employers. These on-screen servants were “always around when the boss needed them…[and] always ready to lend a helping hand when times were tough” (36). Historian Donald Bogle dubbed this era of Hollywood the “Age of the Negro Servant,” referenced in this reel from the New York Times.

—-

.

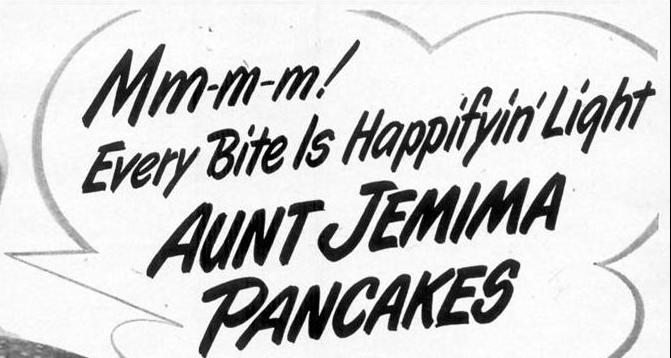

Cinema and television merely built from years of audible racism on the radio—America’s most prominent form of in-home entertainment in the first half of the 20th century—where Black actors also played largely servant and maid roles that demanded they speak in “distorted dialect, exaggerated intonation, rhythmic speech cadences, and particular musical instruments” in order to appear at all (143). This white-contrived portrayal of Black people is known as “Blackvoice,” and essentially functions as “the minstrel show boiled down to pure aurality” (14). These performances allowed familiar ideals of and narratives about Blackness to be communicated and recirculated on a national scale, even without the presence of Black bodies. Labor-performing Black characters like Beulah, Molasses and January, Aunt Jemima, and Amos and Andy were prominent in the Golden Age of Radio, all initially voiced by white actors. In fact, Aunt Jemima’s print advertising was just as dependent on stereotypical representations of her voice as it was on visual “Mammy” imagery.

When Black actors broke through white exclusion on the airwaves, many took over roles once voiced by white men and/or were forced by white radio producers and scriptwriters to “‘talk as white people believed Negroes talked’” so that white audiences could discern them as Black (371). This continuous realignment undoubtedly informs contemporary ideas of labor, labor performance, and laboring bodies, further promoted by the sudden influx of Black voice assistants in 2019.

Specifically, these similarities demonstrate that contemporary IVAs are intrinsically haunted by Black women slaves and servants: built in accordance with and thus inevitably evoking these laborers in their positioning, programming, and task performance. Further facilitating this alignment is the fact that advertisements for Black-voiced IVAs purposefully link well-known Black bodies in conjunction with their Black voices. Excepting Apple’s Black-sounding voice options for Siri, all of the Black IVA voice options since 2019 have belonged to prominent Black American celebrities. Prior to Issa Rae, GA users could employ John Legend as their digital aide (April 2019 until March 2020). Samuel L. Jackson became the first celebrity voice option for Amazon’s Alexa in December 2019, followed by Shaquille O’Neal in July 2021.

The ads for Black-voiced IVAs thus link these disembodied aides not just to Black bodies, but to specific Black bodies as a sales tactic—bodies which signify particular images and embodiments of Blackness. The Samuel L. Jackson Alexa ad utilizes close-ups of Jackson recording lines for the IVA and of Echo speakers with Jackson’s voice emitting from them in response to users. John Legend is physically absent from the ad announcing him as the GA; however, his celebrity wife directs the GA to sing for her instead, after which she states that it is “just like the real John”—thus linking Legend’s body to the GA even without his onscreen presence. Amazon has even explicitly explored the connection between the Black-voiced IVA and the Black body, releasing a 2021 commercial called “Alexa’s Body” that saw Alexa voiced and physically embodied by Michael B. Jordan—with the main character in the commercial insinuating that he is the ideal vessel for Alexa.

By aligning these bodies with, and having them act as, labor-performing devices in service of consumers, these advertisements both re-align Blackness with labor and illuminate how these devices were always already haunted by laboring Black bodies—and especially, given the demographics of the bodies who most performed the types of labors IVAs now execute, laboring Black women’s bodies. That the majority of the Black celebrities employed as Black IVA voices are men suggests some awareness of and attempt to distance from this history and implicit haunting—an effort which itself exposes and illuminates the degree to which this haunting exists.

In some cases, the Black people lending their voices to these IVAs also speak in a way that sonically suggests Blackness: Issa Rae’s “Now I’m just extra fly,” for example, incorporates Black American slang through the use of the word “fly. As part of African American Vernacular English (AAVE), the term “fly” dates back to the 1970s and denotes coolness, attractiveness, and fashionableness. Because of its inclusion in Hip Hop, which has become the dominant music genre in the United States, the term, its meaning, and its racial origins are widely known amongst consumers. By using the word “fly,” Rae nods not only at these qualities but also at her own Blackness in a manner that is recognizable to a mainstream American audience. Due in part to Hip Hop’s popularity, U.S.-based media outlets, corporations, and individuals of varying races and ethnicities regularly appropriate AAVE and Black slang terms, often without regard for the culture that created them or the vernacular they stem from. The ad preceding Issa Rae’s revelation as the GA specifically invited users to align the voice with a celebrity body, and users’ predominant claims that the voice was a Black woman’s suggest that something about the voice conjured Blackness and the Black female body.

This racial marking was also likely facilitated by how people naturally listen and respond to voices. As Nina Sun Eidsheim notes in The Race of Sound, “voices heard are ultimately identified, recognized, and named by listeners at large. In hearing a voice, one also brings forth a series of assumptions about the nature of voice” (12). This series of assumptions, Eidsheim asserts in “The Voice as Action,” is inflected by the “multisensory context” surrounding a given voice, i.e., “a composite of visual, textural, discursive, and other kinds of information” (9). While we imagine our impressions of voices as uniquely meaningful, “we cannot but perceive [them] through filters generated by our own preconceptions” (10). As a result, listening is never a neutral or truly objective practice.

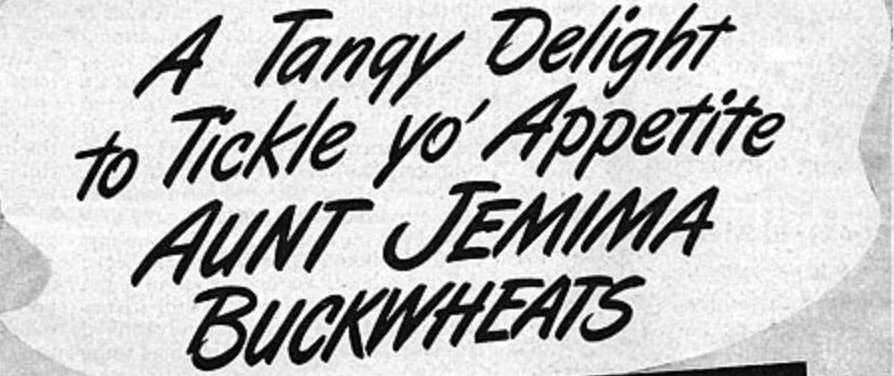

For many consumers, these filters are informed by what Jennifer Lynn Stoever terms the sonic color line, “a socially constructed boundary that racially codes sonic phenomena such as vocal timbre, accents, and musical tones” (11). Where the racial color line allows white people to separate themselves from Black people on the basis of visual and behavioral differences, the sonic color line allows people “to construct and discern racial identities based on voices, sounds, and particular soundscapes” and to assign nonwhite voices with “differential cultural, social, and political value” (11). In the U.S., the sonic color line operates in tandem with the American listening ear, which “normalizes the aural tastes and standards of white elite masculinity as the singular way to interpret sonic information” (13) and therefore marks-as-Other not only the voices and bodies of Black people, but also those of non-males and the non-elite.

Ironically, the very listening practices which make consumers register particular voices and vocal qualities as Black also make Black voices inaccessible to Alexa and other IVAs. Scholarship on Automated Speech Recognition (ASR) systems and Speech AI observes that many Black users find it necessary to code-switch when speaking to IVAs, as the devices fail to comprehend their linguistic specificities. A study by Christina N. Harrington et al. in which Black elders used the Google Home to seek health information discovered that “participants felt that Google Home struggles to understand their communication style (e.g., diction or accent) and language (e.g., dialect) specifically due to the device being based on Standard English” (15). To address these struggles, participants switched to Standard American English (SAE), eliminating informal contractions and changing their tone and verbiage so that the GA would understand them. As one of the study’s participants states,

You do have to change your words. Yes. You do have to change your diction and yes, you have to use… It cannot be an exotic name or a name that’s out of the Caucasian round. …You have to be very clear with the English language. No ebonic (15).

This incomprehension extends to Black Americans of all ages, and to other IVAs. A study by Allison Koenecke et al. on ASR systems produced by Amazon, Google, IBM, Microsoft and Apple discovered that these entities had a harder time accurately transcribing Black speech than white speech, producing “an average word error rate (WER) of 0.35 for black speakers compared with 0.19 for white speakers.” (7684). A study by Zion Mengesha et al. on the impact of these errors on Black Americans—which included participants from different regions with a range of ages, genders, socioeconomic backgrounds and education-levels—discovered that many felt frustrated and othered by these mistakes, and felt further pressure to code-switch so that they would not be misunderstood. Koenecke et al. concluded that ASR systems could not understand the “phonological, phonetic, or prosodic characteristics of” AAVE (7687), and that this ignorance would make the use of these technologies more difficult for Black users—a sentiment that was echoed by participants in the study conducted by Mengesha et al., most of whom marked the technology as working better for white and/or SAE speakers (5).

The speech recognition errors these technologies demonstrate—which also extend to speakers in other racial and ethnic groups—illuminate the reality that despite including Black voices as IVAs, these assistant technologies are not truly built for Black people, or for any person that does not speak Standard American English. And where AAVE is largely associated with Blackness, SAE is predominantly associated with whiteness: as a dialect widely perceived to be “lacking any distinctly regional, ethnic, or socioeconomic characteristics,” it is recognized as being “spoken by the majority group or the socially advantaged group” in the United States—both groups which are solely or primarily composed of white people. SAE is so identified with whiteness that Black people who only speak Standard English are often told that they sound and/or “talk” white, and Black people who deliberately invoke SAE in professional and/or interracial settings (i.e., code switching) are described as “talking white” or using their “white voice” when doing so. That IVAs and other ASR systems have such trouble understanding AAVE and other non-standard English dialects suggests that these technologies were not designed to understand any dialect other than SAE—and thus, given SAE’s strong identification with whiteness, were designed specifically to assist, understand, and speak to white users.

Writing on this phenomena as a woman with a non-standard accent, Sinduja Rangarajan highlights in “Hey Siri—Why Don’t You Understand More People Like Me?” that none of the IVAs currently on the market offer any American dialect that is not SAE. And while users can change their IVA’s accents, they are limited to Standard American, British, Irish, Australian, Indian, and South African—which Rangarajan rightly highlights as revealing who the IVAs think they are talking to, rather than who their user actually is. That most of these accents belong to Western, predominantly white countries (or to countries once colonized by white imperialists) strongly suggests that these devices are programmed to speak to—and perform labor for—white consumers specifically.

When considering the primary imagined and target users of IVAs, the sudden influx of Black-voiced IVAs becomes particularly insidious. Though they may indeed make some Black users feel more represented, cultivating this representation is merely a byproduct of their actual purpose. Because these technologies are not built for Black consumers, Black-voiced IVAs are meant to appeal not to Black users, but to white ones. Rae, Jackson, and the other Black celebrity voices may provide a much-needed variety in the types of voices applied to IVAs, but they primarily operate as “further examples of technology companies using Black voices to entertain white consumers while ignoring Black consumers.” Black-voiced assistants, after all, no better understand Black vernacular English than any of the other voice options for IVAs, a reality marking Black speech patterns as enjoyable but not legitimate.

By excluding Black consumers, the companies behind these IVAs insinuate that Blackness is only acceptable and worthy of consideration when operating in service of whiteness. Where Black people as consumers have been delegitimized and disregarded, Black voices as labor-saving assistants have been welcomed and deemed profitable—a reality which further emphasizes how historical constructions of Black people as labor-performing devices haunts these contemporary technologies. Tech companies reinforce historical positionings of white people as ideal consumers and Black people as consumable products—repeating historical demarcations of Blackness and whiteness in the present.

In imagining the futures of IVAs, the companies behind them would need to reconsider how they interact—or fail to interact—with Black users. Both Samuel L. Jackson and Shaquille O’Neal, the last of the Black-celebrity-voiced IVAs still currently available to users, will be removed as Alexa voice options by September 2023, presenting an opportunity for these companies to divest. Whether or not the brands behind these IVAs take this initiative, consumers themselves can be critical of how AI technologies continue to reestablish hierarchical systems, of their own interactions with these devices, and of who these technologies are truly made for. In being critical, we can perhaps begin to envision alternative, reparative modes of AI technology—modes that serve and support more than one kind of user.

—

Featured Image: Issa Rae gif from the 2017 Golden Globes

—

Golden Marie Owens is a PhD candidate in the Screen Cultures program at Northwestern University. Her research interests include representations of race and gender in American media and popular culture, artificial intelligence, and racialized sounds. Her doctoral dissertation, “Mechanical Maids: Digital Assistants, Domestic Spaces, and the Spectre(s) of Black Women’s

Labor,” examines how intelligent virtual assistants such as Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa evoke and are haunted by Black women slaves, servants, and houseworkers in the United States. In her time at Northwestern, she has had internal fellowships through the Office of Fellowships and the Alice Kaplan Institute for the Humanities. She currently holds an MMUF Dissertation Grant through the Institute for Citizens and Scholars and Ford Dissertation Fellowship through the National Academy for Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Beyond the Every Day: Vocal Potential in AI Mediated Communication –Amina Abbas-Nazari

Voice as Ecology: Voice Donation, Materiality, Identity–Steph Ceraso

Mr. and Mrs. Talking Machine: The Euphonia, the Phonograph, and the Gendering of Nineteenth Century Mechanical Speech – J. Martin Vest

Echo and the Chorus of Female Machines—AO Roberts

Black Excellence on the Airwaves: Nora Holt and the American Negro Artist Program —Chelsea Daniel and Samantha Ege

Spaces of Sounds: The Peoples of the African Diaspora and Protest in the United States–Vanessa Valdes

On Whiteness and Sound Studies–Gus Stadler

Recent Comments