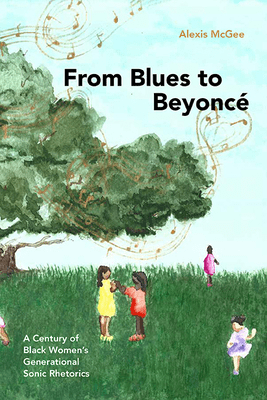

SO! Reads: Alexis McGee’s From Blues To Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics

From Blues To Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics (SUNY Press, 2024) by Alexis McGee explores Black women’s creative labor and cultural production. The book offers a searing critique of both record industry exploitation and sound studies’ white gaze. By focusing on quotidian engagement with sound, McGee speaks simultaneously to linguists, rhetoricians, and ethnomusicologists, demonstrating how each discipline has overlooked Black women’s fundamental contributions to our understanding of language and cultural expression. This is not merely an additive project seeking inclusion within existing frameworks, but rather a fundamental reconceptualization of how we study Black women’s sounds.

McGee, currently Associate Professor at the University of British Columbia’s School of Journalism, Writing, and Media, mobilizes her training in linguistics, rhetoric, and composition to analyze everyday communicative practices and generational knowledge systems passed down between Black women. McGee joins other recent texts such as Earl Brooks’s On Rhetoric and Black Music (2024) in critical conversations around “sonic rhetoric.” In From Blues to Beyoncé, McGee theorizes sonic rhetoric as a collection of cultural technologies for storytelling that “act as methods of communicating knowledge that can be used to persuade or inform (younger) generations about topics like survival, liberation, and care” (6). Examining artists from the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries through personal experience, archival material, biographies, interviews, and popular media, McGee demonstrates the critical necessity of taking seriously the generational cultural knowledge embedded in Black women’s creative practices within an anti-Black and misogynist world.

At its core, the book introduces “sonic sharecropping” as a term that illuminates the lopsided relationship between Black women creatives (tenants), their sonic and musical creations (crops), and wealthier, more powerful recording industry players (landlords, music labels, copyright holders). The sharecropping metaphor reveals how the music industry extracts value from Black women’s cultural labor while denying them ownership and fair compensation. McGee further develops the concept of “audibility of advice” to name the intergenerational mentorship and fugitive pedagogy that Black women practice as they navigate this exploitative system—showing how even the transmission of survival knowledge between generations becomes entangled in the same structures designed to profit from Black women’s creative work.

The book’s chapters traverse an impressive range of cultural moments. Opening with Cardi B’s attempted trademark of “okurrr,” McGee demonstrates how legal and social structures systematically prevent Black women from securing intellectual property rights over cultural innovations that white industry executives appropriate without restriction.

This contemporary case illuminates sonic sharecropping: Black women are expected to create cultural property that record labels then own and sell back to them. McGee then traces these dynamics historically, analyzing business practices of major labels like Atlantic Records. By drawing parallels between sharecropping contracts and recording agreements, the analysis reveals how the music industry has historically relied on discretionary ethical conduct by executives rather than equitable contractual structures, perpetuating exploitative relationships reminiscent of post-Reconstruction economic arrangements.

In what is perhaps the book’s most compelling chapter, McGee examines successive performances of “Strange Fruit,” tracing how Nina Simone and later artists like Missy Elliott and Janelle Monáe have reinterpreted Billie Holiday’s haunting meditation on lynching.

McGee builds on Amiri Baraka’s concept of the “changing same”, to show that antiblackness persists throughout time though it changes form. McGee demonstrates how Black women performers resist being treated as interchangeable vessels for Black cultural expression. Rather than presenting generic renditions, each artist asserts her distinctive voice and perspective that reiterates the enduring violence perpetuated against Black bodies.

Each performance carries its own rhetorical power while participating in “sankofarration,” a neologism from artist, writer, and media studies professor John Jennings that combines “sankofa” (a West African concept symbolizing learning from the past to move forward) with “narration” to describe a rhetorical worldview premised on understanding time as cyclical rather than linear. Sankofarration positions past and future as interconnected forces that actively shape the present. Crucially, McGee connects Lawrence Beitler’s commercial sale of lynching photographs (depicting the hanged bodies of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith) to the visual and sonic rhetorical devices in these musical works. Through this framework, Black women artists transform historical trauma into ongoing political commentary and visions for future liberation. Black women’s creative work, she argues, consistently foregrounds documented histories of racial violence alongside the willful ignorance that upholds white supremacy and patriarchy. By listening critically to Black women’s sonic rhetorics, we can access pathways toward collective liberation.

Despite the book’s title, McGee’s engagement with Beyoncé focuses narrowly on the lemon-to-lemonade metaphor in the album, Lemonade. Her analysis of other Black women artists, however, anticipated critiques later directed at Cowboy Carter, highlighting a double standard: as a Black woman, Beyoncé faces moral scrutiny for engaging with country music—positioned as both capitalist enterprise and white cultural property—while white and male artists have participated in the same commercial structures for centuries without comparable ethical condemnation.

This defense raises the book’s most provocative question, one McGee gestures toward but leaves unresolved: if the inequitable standards applied to Black women artists are symptoms of a fundamentally exploitative system, what would liberation from that system actually entail? Does it require dismantling existing structures of cultural ownership and profit, or can it be achieved through expanded access and recognition within them?

While McGee does not directly engage Matthew Morrison’s recent work Blacksound: Making Race and Popular Music in the United States, her analysis clearly converses with his examination of how Black cultural products have been reproduced for white consumption, particularly through the ongoing afterlives of blackface minstrelsy. McGee’s focus on Black women specifically adds crucial gender analysis to ongoing scholarly conversations about racial capitalism and cultural appropriation.

McGee acknowledges that capitalism itself, rather than Black women’s participation in it, constitutes the fundamental problem. However, the analysis stops short of fully theorizing alternatives to existing structures of Western sound production and commodification. Readers familiar with Sylvia Wynter’s insistence on distinguishing the map from the territory, or Audre Lorde’s warning that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” may desire more sustained engagement with radical alternatives and additional tool building necessary for Black liberation from existing antiblack social and political structures. What might Black women’s sonic practices look like in anticapitalist frameworks of collective ownership and exchange? How might Black femme and queer performances expand or complicate these intergenerational transmissions of knowledge? How might Black women’s intergenerational knowledge systems point toward alternative epistemologies that refuse the terms of racial capitalism altogether?

This theoretical restraint appears strategic rather than accidental. From Blues to Beyoncé navigates carefully between colleagues unfamiliar with Black feminist and womanist theory, who require accessible entry points, and specialists seeking new takes on traversing multiple disciplines at once. In threading this needle, McGee prioritizes disciplinary bridge-building before radical dismantling of capitalist structures and academic knowledge production systems.

These limitations notwithstanding, the book represents an essential contribution to multiple fields. It insists that scholars of sound studies, rhetoric, and Black feminist thought must engage one another—that these conversations can no longer proceed in isolation. Methodologically, it offers both theoretical sophistication and practical analytical tools, making it intellectually substantive for non-specialists while providing specialists a compelling model for interdisciplinary synthesis. Most importantly, McGee demonstrates that we cannot understand American culture, sound, or rhetoric without recognizing Black women’s voices as foundational rather than supplementary.

This book transforms its disciplines by interrogating their foundational assumptions, asking us not simply to include Black women in sound studies, but to recognize how their systematic exclusion has rendered the entire field epistemologically incomplete. In raising these questions, even without fully resolving them, McGee provides both rigorous foundation and invitation to continue the work.

—

Featured Image: Janelle Monae on the Dirty Computer Tour at Madison Square Garden in 2018 by Flickr User Raph_PH. License: CC BY 2.0

—

Joe Zavaan Johnson (he/they) is a multi-instrumentalist, arts educator, and Black music researcher. Currently an Ethnomusicology Ph.D. Candidate at Indiana University-Bloomington, he examines the Black banjo renaissance through Black studies, human geography, folklore, and ethnomusicology. Johnson frequently collaborates with grassroots organizations focused on coalition building, community healing, and cultural reparations, bridging scholarship with community-engaged practice. His forthcoming dissertation, Black Banjo Bodylands: Recovering an African American Instrument, explores the relationship between Black people, lands, and banjos as ancestral technology.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings –Vanessa Valdés

SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests––Jonathan Stone

“I’m on my New York s**t”: Jean Grae’s Sonic Claims on the City--Liana Silva

Love and Hip Hop: (Re)Gendering The Debate Over Hip Hop Studies--Travis Gosa

My Music and My Message is Powerful: It Shouldn’t Be Florence Price or “Nothing”-Samantha Ege

I Been On: BaddieBey and Beyoncé’s Sonic Masculinity — Regina Bradley

Cardi B: Bringing the Cold and Sexy to Hip Hop–Ashley Luthers

Caterpillars and Concrete Roses in a Mad City: Kendrick Lamar’s “Mortal Man” Interview with Tupac Shakur

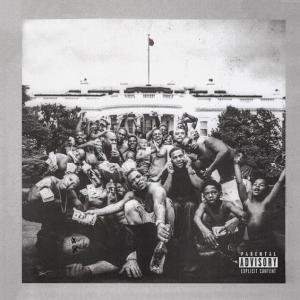

I’ve been hesitant to write about Kendrick Lamar’s 2015 album To Pimp a Butterfly (TPAB) because there are layers to the shit. Sonic, cultural, and political layers that need time to breathe and manifest. Some of those layers are pedagogical. For example, Brian Mooney brilliantly paired the album with Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye to help students work through themes of Black consciousness and self-love. Mooney’s lesson plan garnered Lamar’s attention and a recent visit with Mooney students. Lamar’s open grappling with art and blackness throw him into heavy debates about his worth as a cultural and even literary icon. Yet Lamar’s formula of introspective angst – the use of battling his own demons to shed light on broader American society – pulls me to think about how Lamar and TPAB fit into a long standing trajectory of Black folks’ self-examination in art as a frame for larger critiques of racial politics in American society.

I’m drawn to TPAB’s outro of the final track of the album “Mortal Man.” “Mortal Man” sonically invokes Lamar’s struggle to assume a position as a gatekeeper of a branch of hip hop that focuses on Black community and self-actualization. The track includes a sample from a 1994 Tupac Shakur interview with Swedish music journalist Mats Nileskär. Lamar positions himself as the interviewer, asking a different set of questions that engages Shakur about walking the fault lines of fame, fortune, and Black consciousness in this current cycle of hip hop. The construction and execution of the interview revisits the lines between hip hop’s collective and generational responsibilities via Lamar and Shakur’s interaction. Their conversation moves from creative (and creating) political protest to larger philosophical questions within hip hop: self-consciousness, mortality, and death. Lamar parallels his angst with Tupac using his voice, with Tupac himself heralded as hip hop’s martyred t.h.u.g. with a conscience. In this contemporary moment where Black men’s mortality and worth is attached to being a thug and a problem, Lamar poses Shakur in “Mortal Man” as a keystone for connecting popular scripts with cultural expectations of Black masculinity and agency in the United States.

The song “Mortal Man” launches the interview. The track can be considered a double sample – it uses Houston Person’s cover of Fela Kuti’s song “I No Get Eye for Back.” Lamar’s voice is clear but the background track soft and subdued, forcing the listener to pay full attention to Lamar’s voice, which interrogates what it takes for one to be loyal or respected in mainstream America. Percussion (bass kicks, acoustic drums, soft piano chords) and bass guitar chords annotate Lamar’s solemn lyrical delivery. A horn and woodwind medley – lead by Houston’s tenor sax playing – punctuate Lamar’s chorus:

When the shit hit the fan, is you still a fan?

When the shit his the fan, is you still a fan?

Want you to look to your left and right, make sure you ask your friends

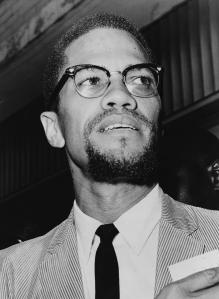

The instrumental accompaniment is soft and steady, suggesting Lamar’s question is a continuous negotiation or checklist for one’s proclamation of loyalty and respect. Lamar’s repetition of “when the shit hit the fan is you still a fan” addresses his fanbase and the followers of other notable Black cultural and creative leaders. They, like Lamar, are usefully flawed – whether by accusation or self-proclamation – and use their flaws to further their cause. Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Moses, Malcolm X, and Michael Jackson all exhibited social-cultural and political agency for (Black) folks. Yet they also suffered scrutiny and disregard because of their personal lives or less-than-respectable experiences.

Malcolm X at Queens Court. Source=Library of Congress. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c11166 Author=Herman Hiller, World Telegram staff photographer

I am especially intrigued by Lamar’s reference to Malcolm X as “Detroit Red,” a nickname X had as a young hellraiser before his conversion to Islam. Lamar’s reference to X in his youth here speaks to larger questions of respectability, Black youth, and protest. Detroit Red is young, flawed but influential, similar to Lamar and other young Black folks leading protests in this contemporary moment. Lamar’s roll call suggests a struggle with the question of authority, both as a creator of Black culture and how his music implies a larger struggle of contemporary Black agency and angst. Interviewing Tupac brings Lamar’s struggle to a head, evoking Shakur’s voice as a culturally recognizable authority of hip hop’s commercial progress and cultural process. The trope of a flawed nature as a departure point for creative expression and agency is a theme that runs throughout TPAB and the rest of Lamar’s musical catalogue.

The musical accompaniment to the “Mortal Man” song fades out and against a backdrop of silence Lamar begins to recite what he states is an unfinished piece. He begins, “I remember when you was conflicted,” which implies he is talking to himself or talking to someone else. The background silence that leads to Lamar and Shakur’s conversation is as telling as the conversation itself, sonically alluding both to Lamar’s ‘quiet’ struggles of self-affirmation and the possibility that someone other than the audience is listening. The quiet is Lamar’s moment of clarity; the listeners are with him at his most vulnerable moment. He uses the silence to focus attention on himself and without the ‘outside noise’ of others’ beliefs and impressions of his music and purpose.

Although the interview takes place over 20 years earlier, Tupac’s answers are clear and ‘live.’ Shakur’s initial voice is pensive and calculating – he sounds like he is thinking through his responses as he speaks – but later sounds more relaxed, laughing and talking louder and faster. The decreasing formality of Shakur’s answers suggests his increasing comfort with the interviewer as well as confidence in his own answers (and ultimately in sharing his beliefs). Lamar’s use of Shakur’s voice serves as the ultimate form of crate digging, using an obscure (or rare) radio interview sample to create his own voice in hip hop. Lamar’s engagement with Shakur serves memory as a cultural archive and as a cultural production. He not only preserves Shakur’s legacy in his own words but uses Shakur as a departure point for how to blur acts of listening for hip hop fans in a digital age.

The act of listening takes center stage for the interview. The interview is presented as an informal sitdown, reminiscent of what takes place during studio sessions: artists share new material and garner advice from veteran artists. Both rookies and veteran artist listen for new perspectives and listening for suggestions to approach a topic or track. Listening here shows Lamar’s awe and respect of Shakur’s perspective and artistry but also hints at how his conversation with Shakur is ultimately a conversation with himself. Lamar starts the conversation with an unfinished piece about his angsts regarding commercial success and how it conflicts with his creative process. He then moves on to asking Shakur about how he grapples with his creative and political consciousness. The listening work taking place here is critical and archival: without Lamar’s (and Lamar’s audience) interest in Shakur’s creative process his voice loses authority and ultimately its power.

Tupac’s sonic ‘resurrection’ signifies his lasting effect in hip hop while serving as a springboard for Lamar’s own pondering about the purpose of his music and the burden of its success. Unlike the visual representation of Shakur via hologram at the 2012 Coachella Music Festival, Lamar’s use of Tupac’s sonic likeness offers an alternative entry point for engaging Tupac’s work outside of his rapping. For example, much of Shakur’s social-political work takes place in his poetry i.e. his collection of poetry The Rose that Grew from Concrete. Further, the ‘thingness’ of the hologram, a physical and technological manifestation of hip hop fans’ and artists’ revering of Tupac’s image and death, makes me think about the type of work the hologram was expected to perform as compared to the sonic ‘ghostliness’ of Tupac’s voice on Lamar’s track. If, as John Jennings suggests, the hologram manifested Tupac as a “ghost in the machine,” how does Tupac’s voice work as a ghost in the machine? On a visceral level hearing Tupac’s voice in conversation with Kendrick Lamar stirs feelings about whether or not he is dead or alive and his immortality as a hip hop icon.

Where the Coachella hologram visualized Tupac Shakur spirit, “Mortal Man” sonically evokes his spirit and the connection between his (im)mortality and storytelling. Lamar says: “Sometimes I be like. . .get behind a mic and I don’t what type of energy I’ma push out or where it comes from.” Shakur responds “because the spirits, we ain’t really even rappin’, we just letting our dead homies tell stories for us.” Listening to Shakur’s use of “we” out of historical context – the interview took place in 1994, 21 years before “Mortal Man” – suggests that Tupac himself is among the dead. He is a “dead homie” and telling a story that Lamar himself is trying to relay to his audience and himself. Yet the lingering possibility of Tupac’s mortality – most embodied in Tupac’s silence after Lamar’s discussion of the significance of a caterpillar to the album – is a powerful moment of protest. Shakur’s quiet and Lamar’s attempt to “call him back,” signifies a period in the conversation. Lamar is left to fend for himself, fighting a “fight he can’t win.” There is also the possibility that his exchange with Shakur is “just some shit he wrote,” an unfinished idea and story that he is still figuring out. Lamar’s rendering of Tupac’s voice makes me think about the DJ Spooky statement “the voice you speak with may not be your own.” Tupac’s ghostly voice and Lamar’s search for his own voice blend to present Tupac as a mouthpiece for not only himself but Lamar.

At surface level Lamar resurrects and interviews Tupac Shakur because of regional ties to West Coast hip hop and a nearly standard declaration in rap of Shakur’s influence and fandom. He is arguably the most celebrated and iconic figure in hip hop. Shakur’s untimely death and open struggles with seeking balance between fame and personal responsibility mold him as hip hop’s shining prince. Shakur’s family ties with the Black Panther Party – a member of the Panthers once called him an “eternal cub” – positioned him to use hip hop as a mouthpiece for contemporary Black protest. But Shakur’s branding of protest and hip hop was messy, in part because of a working understanding and maneuvering of his image as controversial and commercially successful.

The “Mortal Man” interview signifies sound’s ability to usefully bridge past and present social, cultural, and political moments. Lamar’s sonic evoking of Tupac Shakur demonstrates hip hop as a space of Black youth political protest. Lamar uses sound to render hip hop temporality and re-emphasize Black popular culture as a departure point for recognizing contemporary Black angst. The shrinking mediums of spaces available to indicate why and how #BlackLivesMatter position the sonic as a work bench for engaging race relations in a deemed post-racial era. The “Mortal Man” interview serves as a blueprint for connecting hip hop to longstanding conversations about Black protest as a (messy) cultural product.

—

Featured image: “Shot by Drew: Kendrick Lamar” by Flickr user The Come Up Show, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

—

Regina Bradley recently completed her PhD at Florida State University in African American Literature. Her dissertation is titled “Race to Post: White Hegemonic Capitalism and Black Empowerment in 21st Century Black Popular Culture and Literature.” She is a regular writer for Sounding Out!

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

I Been On: BaddieBey and Beyoncé’s Sonic Masculinity — Regina Bradley

Saving Sound, Sounding Black, Voicing America: John Lomax and the Creation of the “American Voice”— Toniesha Taylor

Como Now? Marketing “Authentic” Black Music— Jennifer Stoever

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- SO! Reads: Alexis McGee’s From Blues To Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics

- SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

- Impaulsive: Bro-casting Trump, Part I

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments