Listening to #Occupy in the Classroom

Yes, it’s that time again, readers. You are going to have to stop pretending the “Back to School” aisles haven’t been appearing in stores for the past few weeks. We at SO! are here to ease your transition from summer work schedules to the business of teaching and student-ing with our fall forum on “Sound and Pedagogy.” Developed to explore the relationship between sound and learning, this forum blends the thinking of our editors (Liana Silva), recruited guests (D. Travers Scott), and one of the winners of our recent Call For Posts (Jentery Sayers) to explore how listening impacts the writing process, the teachable moment, and the syllabus (and vice versa). We hope to inspire your fall planning–whether or not you teach a course on “sound studies”–and encourage teachers and students of any subjects to reconsider the classroom as a sensory space. We also encourage you to share your feedback, tips, and experiences in comments to these posts and on our Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit sites. As I said in the Call for Posts for this Forum: “because teaching is so crucial—yet so frequently ignored at conferences and on campus—Sounding Out! wants to wants to provide a virtual space for this vital discussion.” This conversation will be ongoing: we will also bring you a “Spring Break Brush-Up” edition in 2013 featuring several more excellent posts by writers selected from our open call. Right now, the bell’s about to ring–so take a seat, open those ears, and enjoy this shiny auditory apple of an offering from D. Travers Scott in which he discusses how the sounds of #Occupy invigorated his classroom. And, yes, it will be on the test. —JSA, Editor-in-Chief

Yes, it’s that time again, readers. You are going to have to stop pretending the “Back to School” aisles haven’t been appearing in stores for the past few weeks. We at SO! are here to ease your transition from summer work schedules to the business of teaching and student-ing with our fall forum on “Sound and Pedagogy.” Developed to explore the relationship between sound and learning, this forum blends the thinking of our editors (Liana Silva), recruited guests (D. Travers Scott), and one of the winners of our recent Call For Posts (Jentery Sayers) to explore how listening impacts the writing process, the teachable moment, and the syllabus (and vice versa). We hope to inspire your fall planning–whether or not you teach a course on “sound studies”–and encourage teachers and students of any subjects to reconsider the classroom as a sensory space. We also encourage you to share your feedback, tips, and experiences in comments to these posts and on our Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit sites. As I said in the Call for Posts for this Forum: “because teaching is so crucial—yet so frequently ignored at conferences and on campus—Sounding Out! wants to wants to provide a virtual space for this vital discussion.” This conversation will be ongoing: we will also bring you a “Spring Break Brush-Up” edition in 2013 featuring several more excellent posts by writers selected from our open call. Right now, the bell’s about to ring–so take a seat, open those ears, and enjoy this shiny auditory apple of an offering from D. Travers Scott in which he discusses how the sounds of #Occupy invigorated his classroom. And, yes, it will be on the test. —JSA, Editor-in-Chief

—

In the late fall of 2011, I was teaching a class on cultural studies of advertising. I presented the Occupy Student Debt campaign, a subcategory or spinoff of the larger Occupy movement, while we were examining ways people challenged consumer culture. We discussed education as a commodity and students as consumers. Unsurprisingly, my seniors were dissatisfied consumers. They expressed that what had been advertised to them was a product that guaranteed or at least would strongly increase their chances for quality employment (of course, it was also a product they had worked for years in creating, and one they couldn’t return.) If higher education really did land you the lucrative job it had been advertised as guaranteeing, in theory, then, you would be able to more easily pay off student loan debt. To address this dissatisfaction, I showed them two artifacts: a video from the launch in New York City on November 12, 2011, and the OSD debtors’ pledge*.

In the video, OSD founder Pamela Brown reads the pledge one line at a time, with each line chanted back by others. I played the video in a dark classroom. I also projected it on the room’s main screen, but I didn’t use the room’s amplification system because it sounds too much like an authoritarian public address and disperses the audio in a dominating way. External speakers connected to my laptop made the sound feel, to me, more localized and objectified, something we could focus on rather than an institutional part of the room. The students’ first reaction was, not to the words, but the sound: the verbal relay used at the public demonstration. Brows furrowed and heads cocked quizzically, they asked, “Why are they all repeating the speaker like that?” I explained how this provides additional amplification, but the students’ listening experience was instructive to me. Their unfamiliarity with a sonic practice of vocalization indicated their unfamiliarity with larger practices of collective, public social action.

Listening to OSD, and paying attention to how my students listened to it, informed me of larger contexts they needed to understand and discuss it, in ways that the object of the text did not suggest to me. It made me think about the experience and process of my students’ encountering OSD. I immediately noticed its ambient sounds of city life, which I no longer hear. These sounds of traffic, the acoustics of being surrounded by buildings, etc. gave several urban dimensions to the movement the pledge text did not. From the perspective of Upstate South Carolina, “urban” is not a simple thing, an identity or geography category, but intersectional: our largest city, Greenville, has a population under 60,000. City noises feel not merely urban, but un-Southern, and thereby alien. (I say un-Southern rather than Northern or Yankee because another thing I’ve learned here is the inadequacy of that binary: Los Angeles, for example, is not a Northern city but most certainly is as un-Southern as New York. Cities also carry a class dimension.) Even though my school is one of the elite institutions in this area, this region is still worse off economically than the rest of the country and has a generally lower cost of living. Cities require money to live in. In spatial, class, and urban dimensions, OSD felt alien.

Opening of the Occupy Student Debt Campaign, Image by Flickr User JohannaClear

The experience of listening to the ODS rally illustrates how a sound studies perspective foregrounds experiential processes over exclusive categories of things and ideas. For example, when I read the OSD Debtors’ Pledge aloud to my students—vocalizing the text and sounds and listening to them— it brought the text into my body, making it an action. It also made students uncomfortable. Even just a round-robin reading of theory seems to make then anxious and fidgety. While I try to understand and accommodate anxieties around public speaking, I think the way sound makes a text enter the body can be a powerful affective experience. And no one ever said the classroom always had to be comfortable. For me, reading the text aloud personalized the OSD pledge. It evoked sensory memories: “Pledge of” evoked saying the pledge of allegiance in public school; saying “We believe” took me to attending Lutheran church services with my husband at the time where they collectively recite the Apostles’ Creed. These associations evoked emotional disidentifications from organized religion and mandatory collective professions of patriotism. It also temporalized and spatialized OSD for me, positioning it in relations to Dallas, Texas in the 1970s and Greenville, SC today.

Overall, the reading aloud of the pledge staged a tension or dialectic of identification and disidentifications. Although I agreed and identified with the sentiments of the movement, several alienating and unsettling aspects of the pledge came through as I read aloud: the blithe collapsings of “we” and “as members of the most indebted generations” made me wary (collectives always do, but so do easy historical assertions. Really? Are we more indebted than indentured servants who came to America, or people born into slavery?), and the sudden shift to first person singular at the very end seemed jarring: (After saying “we” six times, suddenly it’s ‘I’ now – what happened?). Lastly, the numerous alliterations also had an alienating effect, making the text seem sophistic and manipulative, artificial, composed.

The auditory experience of OSD can also provide insight into how we create texts. A video of Andrew Ross shows him presenting the first, “very rough draft” weeks earlier at an OWS event. Listening to him read this different, earlier version underscores the text as process. The pledge is something that developed. While his flat tone and straight male voice do not appeal to me, they do complexify and dimensionalize Brown’s reading, giving it depth. They also show that some things that bothered me in the final version – the collectivity and alliterations – were not there. This intertextual, diachronic listening does not erase troublesome aspects of the ‘final’ text, but it mediates them. I am moved closer to it by listening to its different origin.

Arguably, any of these points could have been arrived at by good ole’ textual analysis. My point is not that listening always should supplant visual modes; sound studies tries to break that false dichotomy by not denigrating or replacing the visual but by elevating the sonic to complementary – not superseding – status. I argue that reading aloud should be a fundamental, basic component of sound studies methodology, as it allows anyone to hear, voice, embody, and experience a text. I not only noticed these aspects sooner through listening – my first time speaking it aloud, despite having read it at least a dozen times before. Moreover, I didn’t just notice them: I felt them on a personal, emotional, level, which spurs thinking and analysis that is, if not completely new and unique, definitely qualitatively different in its potency and urgency.

Listening to OWS, and the OSD in particular, brings insights affective and personal. Yes, I can read a statistic from a survey stating that a certain percentage of participants in OWS feel angry or betrayed. That doesn’t mean anything to me in a specific, personal, and empathetic way – and empathy is crucial for a social movement to garner support. Listening to both Ross and Brown, I am reflective and conflicted over my professional role – no longer a grad student, but certainly not an established scholar like Ross. I feel connected to OSD in ways beyond the literal facts of my debt. Listening draws me into a contemplative, reflexive space beyond a sticky note on my office desk saying “OWS: teachable moment.” I can see a map with big, red OWS circles over Washington D.C. and New York, but I don’t feel the distance from myself and my students in the same way—and this is crucial for my teaching and engaging them in dialogue about what could be the most significant social movements of their lifetimes.

Share this:

“Ain’t Got the Same Soul”

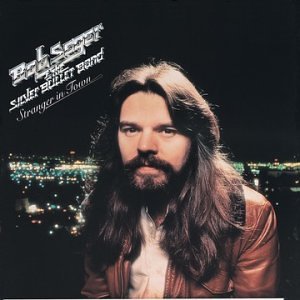

Bob Seger’s “Old Time Rock n’ Roll” has bothered me for a long time. I first heard it in Risky Business in 1983, four years after its initial release, as the soundtrack to a young Tom Cruise frolicking in his tightie-whities to his father’s sacrosanct (and expensive) hi-fi, expressing his repressed white suburban middle-class masculinity and sexuality. It was the song’s vague appeal that got me wondering even back then, how Cruise’s character was even old enough to remember the “old times” that Seger sang of. Hearing it on a “classic rock” station on a recent drive, it suddenly hit me – for many young people the song is a representation of what it clearly isn’t: “old time” rock n’ roll itself.

Bob Seger’s “Old Time Rock n’ Roll” has bothered me for a long time. I first heard it in Risky Business in 1983, four years after its initial release, as the soundtrack to a young Tom Cruise frolicking in his tightie-whities to his father’s sacrosanct (and expensive) hi-fi, expressing his repressed white suburban middle-class masculinity and sexuality. It was the song’s vague appeal that got me wondering even back then, how Cruise’s character was even old enough to remember the “old times” that Seger sang of. Hearing it on a “classic rock” station on a recent drive, it suddenly hit me – for many young people the song is a representation of what it clearly isn’t: “old time” rock n’ roll itself.

The song performs a form of hyper-nostalgia, not only eliding all potentially negative aspects of the “old times”—such as the racial erasure at rock n’ roll’s emergence into the mainstream—but eschewing any kind of specificity about “old time rock n’ roll” altogether. The song’s lyrical and sonic vagueness, punctuated by bland guitar solos and cheesy piano rolls, hearkens to an undefined sense of authenticity that casts doubt on other musical forms and implicitly marks itself as legitimate and authentic – laying a kind of homogeneous claim on rock itself.

The key phrase to Seger’s song, “Today’s music ain’t got the same soul / I like that old time rock n’ roll,” is leavened with irony, because it could be used as an example of “today’s music” itself – at least contemporary to the release of the song in 1979. And let’s face it, “Old Time Rock ‘n Roll” itself seems to be lacking in the soul department. Now, “soul” is a shibboleth. It is a call to a form of racial authenticity that many assume blacks have a natural, essential access to. When whites allegedly have it–it is something worthy of a NY Times article. However, when used by Seger, “soul” becomes a way of defining authentic music as having an unchanging “feel” anchored in a particular vision of the past. So distant it seems, that the lyrics can give us no real hint as to what constitutes “soul”; listeners are just supposed to know it when they feel it.

And yet, “Old Time Rock n’ Roll” arguably lacks that feel; leaving aside the happy accident of the repeated piano intro and the grain of Bob Seger’s voice, I’d make the argument that any close listening to the musical portions themselves makes the lack of “feeling” in the song evident. The song’s music can only be described as an attempt to present a generic portrait of rock n’ roll sounds, with Chuck Berry guitar licks deprived of all gusto and a sax so filtered it may have come from a late seventies synth. This could be attributable to the fact that Seger is singing over a demo meant as a model for his band to record its own version, but the fact remains that is the cut that was kept and that we all know.

The questions then arise: why so generic? Why the lack of specificity in sound and content?

The answer, I feel, can be found in the two listening practices described in the song and the preference of one over the other. The speaker’s unwillingness to be taken “to a disco / you’ll never even get [him] out on the floor” seems to be putting down a genre of music that emerges from a line of descent in the development of popular music in America that can be traced from the “blues and funky old soul” he claims he’d rather hear – Black American music. “Old Time Rock n’ Roll” can be seen as a kind of anthem of the disco wars, where rock fans violently objected to disco.

The rejection of disco then becomes part of a conflict at the time between “rock” as a dominant mainstream white musical form and disco, which Alice Echols has described in her recent book, Hot Stuff: The Remaking of American Culture, as a heterogeneous site that was black, queer, women-friendly and social and that eschewed the centrality of a ineffable “authenticity” that rock n’ roll always strove for. In order for Bob Seger’s “Old Time Rock n’ Roll” to establish its authenticity, it must contrast itself to disco, accomplishing this not only by pulling rock n’ roll into a personal listening sphere, but by eliding the sexual energy present in early rock n’ roll and still evident in the disco of the 70s. To heap upon this irony, the fact the high-hat cymbal moves into a disco off-time beat at several points in the song provides “Old Time Rock n’ Roll” with what catchy-rhythm it does have.

Leaving the disco after 10 minutes along with the opening lines of the song “Just take those old records off the shelf / I sit and listen to them by myself” one gets a sense of an anti-social listening practice that divorces the music he claims to love from its cultural context and transform it into a solitary act. Like nearly all forms of nostalgia, Seger’s view of the past of the music is problematic in its glossing over the complexities and specificities of the time he is ostensibly singing about.

Another one of Seger’s hits may claim that “rock n’ roll never forgets,” but it seems like forgetting might be what it does best. Looking at Bob Seger’s professed influences— Little Richard and Elvis — we can see some of that forgetting in action. If the former suggests that the shifting, slippery, and flamboyant sexuality of disco has been present from rock’s very beginning, then the crowning of the latter as the “King of Rock n’ Roll” highlights just the kind of erasure that allows for a song like “Old Time Rock n’ Roll” to make sense as an anthem of whitewashed “heartland” rock. Seger’s clarion call to old timey-ness strips it of its sex even as he evokes a particular kind of “blackness” through the grain of his voice – a throaty howl full of a representation of sonic authenticity profiting of a vague sense of racial marking. In other words, Seger’s voice performs soulfulness through a growly working-class sound (typified in his “Like a Rock” Chevy commercials), itself a placeholder for race which is verboten in this construction of rock n’ roll. This kind of rock star class passing functions because of the racial erasure the songs enacts by means of white privilege.

Another one of Seger’s hits may claim that “rock n’ roll never forgets,” but it seems like forgetting might be what it does best. Looking at Bob Seger’s professed influences— Little Richard and Elvis — we can see some of that forgetting in action. If the former suggests that the shifting, slippery, and flamboyant sexuality of disco has been present from rock’s very beginning, then the crowning of the latter as the “King of Rock n’ Roll” highlights just the kind of erasure that allows for a song like “Old Time Rock n’ Roll” to make sense as an anthem of whitewashed “heartland” rock. Seger’s clarion call to old timey-ness strips it of its sex even as he evokes a particular kind of “blackness” through the grain of his voice – a throaty howl full of a representation of sonic authenticity profiting of a vague sense of racial marking. In other words, Seger’s voice performs soulfulness through a growly working-class sound (typified in his “Like a Rock” Chevy commercials), itself a placeholder for race which is verboten in this construction of rock n’ roll. This kind of rock star class passing functions because of the racial erasure the songs enacts by means of white privilege.

Richard’s slippery sexuality and the way in which his most famous songs, like “Tutti Frutti” emphasize dance–and dancing as a euphemism for sex: “she rocks it to the east/she rocks it to the west/but she’s the girl that I know best”–brings me back to Seger’s denial of dance and the solitude of his idealized rock n’ roll, and thus back to Tom Cruise in his tightie-whities dancing around by himself in his parents’ fancy suburban Chicago house.

It makes sense that the scene in Risky Business is so isolated, middle-class and white – idealized rock n’ roll has been hijacked out of the heterogeneity of urban centers, and into the mythic American Heartland where white masculine sexuality can be extolled without threat. Seger’s reactionary song makes a world where it is safe for a teen-aged Cruise to enact his youthful rebellion by unproblematically participating in a form of class-passing of his own – lest we forget, the plot of Risky Business has his character playing the part of pimp to earn his way into Princeton – and yet retain his privileged position insulated from further influence of Black America on his music and on his life.

Addendum: Read Aaron Trammell’s 12.6.10 response, “Bob Seger, Champion of Misfits” at https://soundstudiesblog.com/2010/12/06/bob-seger-champion-of-misfits/

Share this:

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- Rhetoric After Sound: Stories of Encountering “The Hum” Phenomenon

- Echoes of the Latent Present: Listening to Lags, Delays, and Other Temporal Disjunctions

- Wingsong: Restricting Sound Access to Spotted Owl Recordings

- Listening Together/Apart: Intimacy and Affective World-Building in Pandemic Digital Archival Sound Projects

- The Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2023!

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments