Listening to the Beautiful Game: The Sounds of the 2018 World Cup

I heard them before I saw them. Walking to my apartment in Moscow’s Tverskoy District, I noticed a pulsating mass of sound in the distance. Turning the corner, I found a huge swath of light blue and white and—no longer separated by tall Stalinist architecture—was able to clearly make out the sounds of Spanish. Flanked by the Izvestiia building (the former mouthpiece for the Soviet government), Argentinian soccer fans had taken over nearly an entire city block with their revelry. The police, who have thus far during the tournament been noticeably lax in enforcing traffic and pedestrian laws, formed a boundary to keep fans from spilling out into the street. Policing the urban space, the bodies of officers were able to contain the bodies of reveling fans, but the sounds and voices spread freely throughout the neighborhood.

Moscow is one of eleven host cities throughout Russia for the 2018 FIFA World Cup, which runs from June 14 to July 15. Over one million foreign fans are expected to enter the country over the course of the tournament, and it is an important moment in Vladimir Putin’s attempt to reassert Russia’s power on the global stage. Already, it has been called “the most political tournament ever,” and discussions of hooliganism, safety concerns, and corruption have occupied many foreign journalists in the months leading up to the start. So gloomy have these preambles been that writers are now releasing opinion pieces expressing their surprise at Moscow’s jubilant and exciting atmosphere. Indeed, it seems as though the whole world is not only watching the games, but also listening attentively to try to discern Russia’s place in the world.

Police officers during World Cup 2018 in Russia, Image by Flickr User Marco Verch (CC BY 2.0)

Thus it comes as no surprise that the politics of sound surrounding the tournament have the potential to highlight the successes, pitfalls, and contradictions of the “beautiful game.” Be it vuvuzelas or corporate advertising, sound and music has shaped the lived experience of the World Cup in recent years. And this tournament is no exception: after their team’s 2-1 win over Tunisia on June 18, three England fans were filmed singing anti-semitic songs and making Nazi salutes in a bar in Volgograd. That their racist celebrations took place in Volgograd, formerly known as Stalingrad and the site of one of the bloodiest battles of World War II, added historical insult and even more political significance. The incident has shaped reception of England fans and their sounds across the country. As journalist Alec Luhn recently tweeted, police cordoned off singing England supporters in Nizhny Novgorod after their victory over Panama, ostensibly keeping the risk of hooliganism at bay. The incident stands in stark contrast with the police barrier around the Argentina fans, who were being protected not from supporters of other nationalities, but rather from oncoming traffic.

England fans in Russia sing songs…behind a line of police. Part of the reason there hasn’t been any hooligan violence pic.twitter.com/RwXz8XtLHf

— Alec Luhn (@ASLuhn) June 23, 2018

More than anything, however, sound has facilitated cultural exchange between fans and spectators. In recent years, historians and musicologists have paid more attention to the multivalent ways musical exchanges produce meaningful political and social understandings. Be it through festivals, diplomatic programs, or compositional techniques, music plays a powerful role in the soft power of nations and can cultivate relationships between individuals around the globe. More broadly, sound—be it organized or not—shapes our identity and is one of the ways by which we make meaning in the world. Sound, then, has the potential to vividly structure the experience of the World Cup—a moment at which sound, bodies, individuals, and symbolic nations collide.

At the epicenter of all of this has been Red Square, Moscow’s—and perhaps Russia’s—most iconic urban space. The site of many fan celebrations throughout the World Cup, Red Square’s soundscape brings together a wide variety of national identities, socio-economic considerations, and historical moments. To walk through Red Square in June 2018 is to walk through over five-hundred years of Russian history, emblematized by the ringing bells and rust-colored walls of the Kremlin; through nearly eighty years of Soviet rule, with the bustle and chatter of curious tourists waiting to enter Lenin’s tomb; and through Russia’s (at times precarious) global present, where fans from Poland join with those from Mexico in chants of “olé” and Moroccan supporters dance and sing with their South Korean counterparts. The past, present, and an uncertain future merge on Red Square, and the sonic community formed in this public space becomes a site for the negotiation of all three.

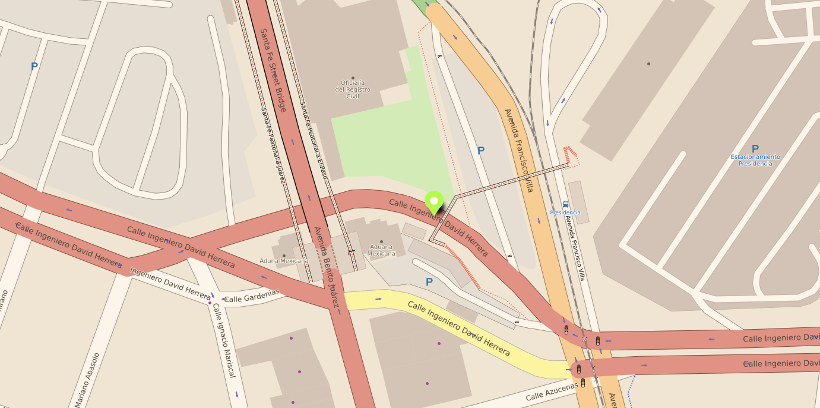

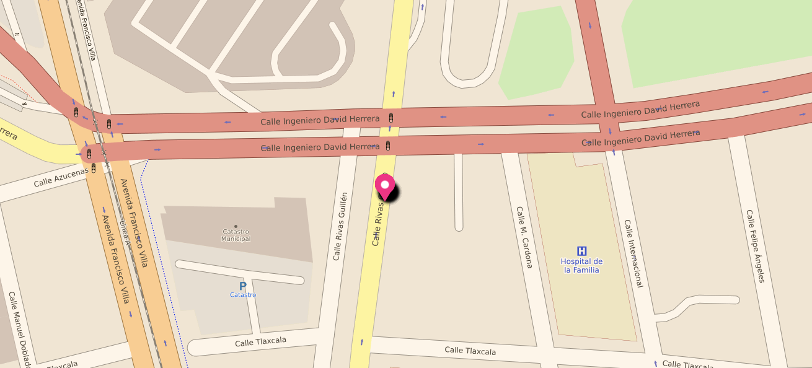

Map of Red Square

In the afternoon of June 19, I walked through Red Square to listen to the sounds of the World Cup outside the stadium. At the entrance to Red Square stands a monument to Grigory Zhukov, the Soviet General widely credited with victory over the Nazis in World War II. Mounted upon a rearing horse, Zhukov’s guise looms large over the square. In anticipation of that evening’s match between Poland and Senegal at Moscow’s Spartak Stadium, Polish fans were gathered at the base of Zhukov’s monument and tried to summon victory through chants and songs (Poland would end up losing the match 2-1.) Extolling the virtues of their star player, Robert Lewandowski, the fans played with dynamics and vocal timbres to assert their dominance. Led by a shirtless man wearing a police peaked cap, the group’s spirit juxtaposed with Zhukov’s figure reiterated the combative military symbolism of sporting events. Their performance also spoke to the highly gendered elements of World Cup spectatorship: male voices far outnumbered female, and the deeper frequencies traveled farther across space and architectural barriers. The chants and songs, especially those that were more militaristic like this one, reasserted the perception of soccer as a “man’s sport.” Their voices resonated with much broader social inequalities and organizational biases between the Women’s and Men’s World Cups.

From there, I walked through the gates onto Red Square and was greeted by a sea of colors and hundreds of bustling fans. Flanked by the tall walls of the Kremlin on one side and the imposing façade of GUM (a department store) on the other, the open square quickly became cacophonous. Traversing the crowds, however, the “white noise” of chatter ceded to pockets of organized sound and groups of fans. Making a lap of the square, I walked from the iconic onion domes of St. Basil’s cathedral past a group of chanting fans from Poland, who brought a man wearing a Brazil jersey and woman with a South Korean barrette into the fold. Unable to understand Polish, the newcomers were able to join in on the chant’s onomatopoeic chorus. Continuing on, I encountered a group of Morocco supporters who, armed with a hand drum, sang together in Arabic. Eventually, their song morphed into the quintessential cheer of “olé,” at which point the entire crowd joined in. I went from there past a group of Mexico fans, who were posing for an interview while nearby stragglers sang. The pattern continued for much of my journey, as white noise and chatter ceded to music and chants, which in turn dissipated either as I continued onward or fans became tired.

Despite their upcoming match, Senegalese fans were surprisingly absent. Compared to 2014 statistics, Poland had seen a modest growth of 1.5% in fans attending the 2018 World Cup—unsurprising, given the country’s proximity to Russia and shared (sometimes begrudgingly) history. Meanwhile, Senegal was not among the top fifty countries in spectator increases. That’s not to say, of course, that Senegalese supporters were not there; they were praised after the match for cleaning up garbage from the stands. Rather, geography and, perhaps, socio-economic barriers delimited the access fans have to attending matches live as opposed to watching them from home. With the day’s match looming large, their sounds were noticeably missing from the soundscape of Red Square.

Later that evening, I stopped to watch a trio of Mexico fans dancing to some inaudible music coming from an iPhone. Standing next to me was a man in a Poland jersey. I started chatting with him in (my admittedly not great) Polish to ask where he was from, if he was enjoying the World Cup so far, and so on. Curious, I asked what he thought of all the music and songs that fans were using in celebrations. “I don’t know,” he demurred. “They’re soccer songs. They’re good to sing together, good for the spirit.”

Nodding, I turned back toward the dancing trio.

“You are Russian, yes?” The man’s question surprised me.

“No,” I responded. “I’m from America.”

“Oh,” he paused. “You sound Russian. You don’t look Russian, but you sound Russian.”

I’d been told before that I speak Polish with a thick Russian accent, and it was not the first time I’d heard that I did not look Russian. In that moment, the visual and sonic elements of my identity, at least in the eyes and ears of this Polish man, collided with one another. At the World Cup, jerseys could be taken off and traded, sombreros and ushankas passed around, and flags draped around the shoulders of groups of people. Sounds—and voices in particular—however, seemed equal parts universal and unique. Emanating from the individual and resonating throughout the collective, voices bridged a sort of epistemological divide between truth and fiction, authenticity and cultural voyeurism. In that moment, as jubilant soccer fans and busy pedestrians mingled, sonic markers of identity fluctuated with every passerby.

I nodded a silent goodbye to my Polish acquaintance and, joining the crowd, set off into the Moscow evening.

—

Featured Image: “World Cup 2018” Taken by Flickr User Ded Pihto, taken on June 13, 2018.

—

Gabrielle Cornish is a PhD candidate in Musicology at the Eastman School of Music. Her research broadly considers music, sound, and everyday life in the Soviet Union. In particular, her dissertation traces the intersections between music, technology, and the politics of “socialist modernity” after Stalinism. Her research in Russia has been supported by the Fulbright Program, the Glenn Watkins Traveling Fellowship, and the Cohen-Tucker Dissertation Research Fellowship from the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies. Other projects include Russian-to-English translation as well as a digital project that maps the sounds and music of the Space Race.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Cauldrons of Noise: Stadium Cheers and Boos at the 2012 London Olympics–David Hendy

Goalball: Sport, Silence, and Spectatorship— Melissa Helquist

Sounding Out! Podcast #20: The Sound of Rio’s Favelas: Echoes of Social Inequality in an Olympic City–Andrea Medrado

Recent Comments