Listening to and as Contemporaries: W.E.B. Du Bois & Sigmund Freud

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

It has been an abundant decade-plus (!!!) since Alexander Weheliye’s Phonographies “link[ed] the formal structure of W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk to the contemporary mixing practices of DJs” (13) and we want to know how folks have thought about and listened with Du Bois in their work in the intervening years. How does Du Bois as DJ remix both the historiography and the contemporary praxis of sound studies? How does attention to Du Bois’s theories of race and sound encourage us to challenge the ways in which white supremacy has historically shaped American institutions, sensory orientations, and fields of study? What new futures emerge when we listen to Du Bois as a thinker and agent of sound?

Over the next two months, we will be sharing work that reimagines sound studies with Du Bois at the center. Pieces by Phillip Luke Sinitiere, Kristin Moriah, Aaron Carter-Ényì, Austin Richey, Julie Beth Napolin, and Vanessa Valdés, move us toward a decolonized understanding and history of sound studies, showing us how has Du Bois been urging us to attune ourselves to it. To start the series from the beginning, click here.

Readers, today’s post (the first of an interwoven trilogy of essays) by Julie Beth Napolin explores Du Bois and Freud as lived contemporaries exploring entangled notions of melancholic listening across the Veil.

–Jennifer Lynn Stoever and Liana Silva, Eds.

When W.E.B. Du Bois began the first essay of The Souls of Black Folk (1903) with a bar of melody from “Nobody Knows the Trouble I See,” he paired it with an epigraph taken from a poem by Arthur Symons, “The Crying of Water”:

O water, voice of my heart, crying in the sand,

All night long crying with a mournful cry,

As I lie and listen, and cannot understand

The voice of my heart in my side or the voice of the sea,

O water, crying for rest, is it I, is it I?

All night long the water is crying to me.

A listener, the poem’s speaker can’t be sure of the source of the sound, whether it is inward or outward. Something of its sound is exiled and resonates with Symons’ biographical position as a Welshman writing in English, an imperial tongue. At the heart of the poem is a meditation on language, communication, and listening. Personified, the water longs to be understood and sounds out the listener’s own interiority that struggles to be communicated. The poem’s speaker hears himself in the water, but he is nonetheless divided from it. If he could understand the source of the sound in a suppressed or otherwise unavailable memory, the speaker might be put back together. But listening all night long, that understanding does not come.

Démontée, Image by Flickr User Alain Bachellier

Together, the poem and song serve as a circuitous opening to Du Bois’ “Of Our Spiritual Strivings,” an essay that grounds itself in Du Bois’ training as a sociologist to detail “the color line,” which Du Bois takes to be the defining problem of 20th century America. The color line is not simply a social and economic problem of the failed projects of Emancipation and Reconstruction, but a psychological problem playing out in what Du Bois is quick to name “consciousness.” As the first African American to receive a PhD from Harvard in 1895, Du Bois had studied with psychologist William James, famous for coining the phrase “the stream of thought” in his modernist opus, The Principles of Psychology (1890). In her study of pragmatism and politics in Du Bois, Mary Zamberlin describes how James encouraged his students to listen to lectures in the way that one “receives a song” (qtd. 81). In his techniques of writing, Du Bois adopts and reinforces the paramount place of intuition and receptivity in James’ thought to conjoin otherwise opposed concepts. Demonstrated by the opening epigraphs themselves, Du Bois’ techniques often trade in a lyricism that stimulates the reader’s multiple senses.

I argue that Du Bois surpasses James by thinking through listening consciousness in its relationship to what we now call trauma. While I will remark upon the specific place of the melody in Du Bois’ propositions, I want to focus on the more generalized opening of his book in the sounds of suffering, crying, and what Jeff T. Johnson might call “trouble.” The contemporary understanding of trauma, as a belated series of memories attached to experiences that could not be fully grasped in their first instance, comes to us not from the scientific discipline of psychology, but rather psychoanalysis.

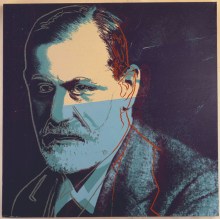

Among the field’s first progenitors, Sigmund Freud, was a contemporary of Du Bois. Though trained as a medical doctor, Freud sought to free the concept of the psyche from its anatomical moorings, focusing in particular on what in the human subject is irrational, unconscious, and least available to intellectual mastery. His thinking of trauma became most pronounced in the years following WWI, when he observed the consequences of shell-shock. Freud discovered a more generalizable tendency in the subject to go over and repeat painful experiences in nightmares. Traumatic repetition, he noted, is a subject struggling to remember and to understand something incredibly difficult to put into words. At the heart of Freud’s methods, of course, was listening and the observations it afforded, grounding his famous notion of the “talking cure.” Because trauma is so often without clear expression, Freud listened to language beyond meaning, beyond what can be offered up for scientific understanding.

Image by Flicker User Khuroshvili Ilya

The beginning of Souls, along with its final chapter on “sorrow songs,” slave song or spirituals, tells us that Du Bois’ project shared that same auditory core. Du Bois was listening to consciousness, that is, developing a theory of a listening (to) consciousness in an attempt to understand the trauma of racism and the long, drawn-out historical repercussions of slavery. Importantly, however, Du Bois’ meditation on trauma precedes Freud’s. But Du Bois’ thinking also surpasses Freud in beginning from the premise that trauma is the sine qua non of theorizing racism, which makes itself felt not only outwardly in social and economic structures, but inwardly in consciousness and memory.

Du Bois claimed that he hadn’t been sufficiently Freudian in diagnosing white racism as a problem of irrationality. He didn’t mean by this that Freud himself made such a diagnosis, but rather that Freud was correct in refusing to underestimate what is least understandable about people. Freud’s thinking, however, remained mired in racist thinking of Africa. Though he claimed to discover a universal subject in the structure of the psyche—no one is free from the unconscious—racist thinking provided the language for the so-called “primitive” part of the human being in drives. This primitivism shaped Freud’s myopic thinking of female sexuality, famously remarking that female sexuality is the “Dark Continent,” i.e. unavailable to theory. Freud drew the phrase from the imperialist travelogues of Henry Morton Stanley in the same moment that Du Bois was turning to Africa to find what he called, both with and against Hegel, a “world-historical people.” As I argue, Du Bois found in the music descended from the slave trade not only a “gift” and “message” to the world, but the ur-site for theorizing trauma.

Ranjana Khanna has shown how colonial thinking was the precondition for Freudian psychoanalysis. Anti-colonial psychiatrist Frantz Fanon, for example, both took up and resisted Freud when he elaborated the effects of racism as the origin of black psychopathology, i.e. feelings of being split or divided. Du Bois, like Fanon after him, was hearing trauma politically as a structural event. The complex intellectual biography of Du Bois, which includes a time of studying (in German) at Berlin’s Humboldt University, mandated that he took from European philosophical interlocutors what he needed, creating a hybrid yet decidedly new theory of listening consciousness. That hybridity is exemplified by the opening of his book, an antiphony between two disparate sources bound to each other across the Atlantic through what I will call hearing without understanding. In this post, I ask what Du Bois can tell us about psychoanalytic listening and its ongoing potential for sound studies and why Freud had difficultly listening for race.

***

“Before the Storm,” Image by Flickr User Marina S.

“Psychoanalysis . . . , more than any twentieth-century movement,” writes Eli Zaretsky in Political Freud, “placed memory at the center of all human strivings toward freedom” (41). He continues, “By memory I mean no so much objective knowledge of the past or history but rather the subjective process of mastering the past so that it becomes part of one’s identity.” In 1919, Freud gave a name to the experience resounding for Du Bois in Symons’ poem “The Crying of Water:” “melancholia.” Unlike mourning after the death of a loved one, whose aching and cries pass with time, melancholia is an ongoing, integral part of subjects who have lost more inchoate things, such as nation or an ideal. This loss, Freud contended, could in fact be constitutive of identity, or the “ego,” Latin for “I” (“is it I? Is it I?” Symons asks). In mourning, one knows what has been lost; in melancholia, one can’t totally circumscribe its contours.

Zaretsky details the way that Freudianism, particularly after its rapid expansion in the US after WWI, became a resource for the transformation of African American political and cultural consciousness, playing a pronounced role in the Harlem Renaissance, the Popular Front, and anti-imperialist struggles. Zaretsky rightly positions Du Bois and his 1903 text as the beginning of a political and cultural transformation, but it is an anachronism to suggest that Freudianism contributed to Du Bois’ early work. Not only does Du Bois’ analysis of “The Crying of Water” predate Freud’s “Mourning and Melancholia” by nearly two decades, the two thinkers were contemporaries. In the years that Freud was writing his letters to Wilhelm Fliess, which became the body of his first book, The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), Du Bois was compiling his previous publications for The Souls of Black Folk, along with writing a new essay to conclude it, “The Sorrow Songs,” a sustained reflection on melancholia and its cultural reverberations in song. 1903 is the year of Souls compilation, not composition.

Du Bois’ thinking of a racialized listening consciousness is not only contemporary to Freud, but also fulfills and outstrips him. To approach Du Bois and Freud as contemporaries involves positioning them as listeners on different, but not opposing sides of what Du Bois calls the “Veil.” It is the psychological barrier traumatically instantiated by racialization, which Du Bois famously describes in the first chapter of Souls. The Veil, Jennifer Stoever describes, is both a visual and auditory figure, the barrier through which one both sees and hears others.

To better define the Veil, Du Bois—like Frederick Douglass before him—returns to a painful childhood scene that inscribed in his memory the violence of racial difference and social hierarchy. Early works of African American literature often turn to memoir, writing their elided subjectivity into history. But we miss something if we don’t recognize there a proto-psychoanalytic gesture. In the middle of a sociological, political essay, Du Bois writes of the painful memory of a little white girl rejecting his card, a gift. In this, we can recognize the essential psychoanalytic gesture of returning to the traumatic past of the individual as a forge for self-actualization in the present.

“Storm Coming Our Way” by Flickr User John

As Paul Gilroy has described, Du Bois’ absorption of Hegel’s thought while at Humboldt cannot be underestimated, particularly in terms of the famous master-slave dialectic. In this dialectic, the slave-consciousness emerges as victorious because the master depends on him for his own identity, a struggle that Hegel described as taking place within consciousness. Like Hegel, Zaretsky notes, Du Bois understood outward political struggle to be bound to “internal struggle against . . . psychic masters” (39). I would state this point differently to note that Du Bois’ traumatic experience as a raced being had already taught him the Hegelian maxim: the smallest unit of being is not one, but two. For Hegel, the slave knows something the master doesn’t: I am only complete to the extent that I recognize the other in myself and that the other recognizes me in herself. That is the essential lesson that an adult Du Bois gleans from the memory of the little girl who will not listen to him. He recognizes that she, too, is incomplete.

The essential difference between psychoanalysis and the Hegelian thrust of Du Bois’ essay, however, is that while a traditional analysand seeks individual re-making of the past—not only childhood, but a historical past that shapes an ongoing political present– Du Bois emphasizes the collective and in ways that cannot be reduced to what Freud later calls the “group ego.” If we restore the place of Du Bois at the beginnings of psychoanalysis and its ways of listening to ego formation, then we find that race, rather than being an addendum to its project, is at its core.

We can begin by turning to a paradigmatic scene for psychoanalytic listening, the one that has most often been taken up by sound studies: the so-called “primal scene.” In among the most famous dreams analyzed by Freud, Sergei Pankejeff (a.k.a. the “Wolf Man”) recalls once dreaming that he was lying in bed at night near a window that slowly opened to reveal a tree of white wolves. Silent and staring, they sat with ears “pricked” (aufgestellt). Pricked towards what? The young boy couldn’t hear, but he sensed the wolves must have been responding to some sound in the distance, perhaps a cry.

“The Wolf Man’s Dream” by Sergei Pankejeff, Freud Museum, London

In “The Dream and the Primal Scene” section of “From the History of An Infantile Neurosis” (1914/1918), Freud concluded that the dream was grounded in the young boy’s traumatic experience of witnessing his parents having sex. Calling this the “primal scene,” Freud conjectured that there must have been an event of overhearing sounds the young boy could not understand. In the letters he exchanged with Fliess, Freud had begun to attend to the strange things heard in childhood as the basis for fantasy life and with it, sexuality.

The primal scene is therefore crucial for Mladen Dolar’s theory in A Voice and Nothing More when he pursues the implications of an unclosed gap between hearing and understanding. In the Wolf Man’s case, it is impossible, Freud writes, for “a deferred revision of the impressions…to penetrate the understanding.” In Dolar’s estimation, the deferred relation between hearing and understanding defines sexuality and is the origin of all fantasy life. This gap in impressions cannot be closed or healed, and, for Jacques Lacan it also orients the failure of the symbolic order to bring the imaginary order to language. From this moment forward, psychoanalytic theory argues the subject is “split,” listening in a dual posture for the threat of danger and the promise of pleasure. Following Lacan, Dolar, Michel Chion, and Slavoj Žižek return to the domain of infantile listening—listening that occurs before a person has fully entered into speech and language—to explain the effects of the “acousmatic,” or hearing without seeing.

After Freud, the phrase “primal scene” has taken on larger significance as a traumatic event that, while difficult to compass, nonetheless originates a new subject position that makes itself available to a collective identity and identification. The original meaning of hearing sexual and libidinal signals without understanding them, I would suggest, holds sway. Psychoanalytic modes of listening, particularly if restored to its political origins in racism, offer resources for what it means to listen beyond understanding, but such thinking of race immediately folds into intersectional thinking of gender and sexuality. Consider the place of the traumatic memory of the little girl who rejects the card. In The Sovereignty of Quiet, Kevin Quashie returns to Du Bois’ primal scene to note how the scene takes place in silence, for she rejects it, in Du Bois’ terms, “with a glance.” I want to expand upon this point to note that where there is silence, there is nonetheless listening. Du Bois is listening for someone who will not speak to him; he desires to be listened to and the card—a calling card—figures a kind of address.

Vintage Calling Card, Image by Flickr User Suzanne Duda

It has gone largely unnoticed that, to the extent that the scene is structured by the master-slave dialectic, it is also structured by desire. This scene of trauma is shattering for both boy and girl. The desire coursing through the scene is suppressed in Du Bois’ adult memory in favor of its meaning for him as a political subject. What would it mean to recollect, on both sides, the trace of sexual (and interracial) desire? In “Resounding Souls: Du Bois and the African American Literary Tradition,” Cheryl Wall notes the scant place for black women in the political imaginary of this text. This suppression, I would argue, already begins in the memory of the girl who appears under the sign of the feminine more generally. The fact that she is white, however, casts a greater taboo over the scene and therefore allows more for a suppression of sexuality in his memory. Du Bois emerges as a political agent disentangled from black women—with one notable exception, the maternal, and this exception demands that we listen with ears pricked to “The Sorrow Songs,” as Du Bois’ early contribution to the psychoanalytic theory of melancholia.

Next week, part two will further explore The Souls of Black Folk as a “displaced beginning of psychoanalytic modes of listening,” emphasizing the African melodies once sung by his grandfather’s grandmother that Du Bois’s hears as a child, as “a partial memory and a mode of overhearing.”

—

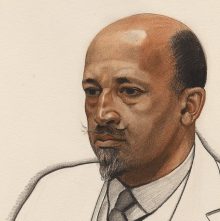

Featured Images: “Nobody Knowns the Trouble I See” from The Souls of Black Folk, Chapter 1, “W.E.B. Du Bois” by Winold Reiss (1925), “Sigmund Freud” by Andy Warhol (1962)

—

Julie Beth Napolin is Assistant Professor of Literary Studies at The New School, a musician, and radio producer. She received a PhD in Rhetoric from the University of California, Berkeley. Her work participates in the fields of sound studies, literary modernism and aesthetic philosophy, asking what practices and philosophies of listening can tell us about the novel as form. She served as Associate Editor of Digital Yoknapatawpha and is writing a book manuscript on listening, race, and memory in the works of Conrad, Du Bois, and Faulkner titled The Fact of Resonance. Her work has appeared in qui parle, Fifty Years After Faulkner (ed. Jay Watson and Ann Abadie), and Vibratory Modernism (ed. Shelley Trower and Anthony Enns).

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“A Sinister Resonance”: Joseph Conrad’s Malay Ear and Auditory Cultural Studies–Julie Beth Napolin

“Scenes of Subjection: Women’s Voices Narrating Black Death“–Julie Beth Napolin

Unsettled Listening: Integrating Film and Place — Randolph Jordan

Scenes of Subjection: Women’s Voices Narrating Black Death

This past summer 2016, U.S. President Barack Obama arrived in Warsaw and delivered an unplanned statement on the brutal police shooting deaths of two black men that had just occurred within one day of each other, Philando Castile in Minnesota and Alton Sterling in Louisiana. Obama was speaking from afar on the structural relationship between two events that should trouble “all of us Americans.” Obama spoke pointedly to the fact of “racial disparity” in police shootings and in the justice system more broadly.

Since November 2016, it has felt as though a space of sanctioned public discourse—still in the making since Reconstruction—has once again become smaller and, in a manner of speaking, unhearing. Quite simply, Obama’s statement meant that identification could not compass the ground of an imagined community. A white listener could not say, as with gun violence in general, “he speaks of someone who could have been me, therefore I am troubled.” Again, identification with white experience asserts itself as the ground of “we.”

The death of Sterling had been captured on cellphone video that showed the police holding him down before shooting him. The video was taken by a store owner who was friendly with Sterling. The ground of a white viewer’s identification is here easily acceded. That viewer might say to him or herself, “I too could know someone who I don’t believe is violent or dangerous; I too might wish to protest or prevent his or her unjust murder.”

still from cell phone video of the police shooting of Alton Sterling, cropping/blurring by JS, SO!

The shooting of Castile by police officer Jeronimo Yanez was not captured on video; there is no visual evidence of the event made by a bystander. Instead, Castile’s dying moments were captured on live video stream by his girlfriend, a black woman, Diamond Reynolds, who orally narrated the immediate aftermath of the event while it was happening. There was no rescue that could have been attempted by Reynolds. Even though Castile was alive and Reynolds’s daughter sat in the back seat, the effort immediately—and of necessity—turned to testimony. The camera—but also narration, putting into words the event that was still unfolding—afforded Reynolds and her daughter some measure of protection against the officer’s gun still aimed in the car. Reynolds no doubt imagined the recording would be used as evidence in a court of law. If she herself did not survive the event, the recording would have already been seen by a public and archived by live stream; her voice would still testify within it.

What does it mean, on an ethical level, for a black woman to narrate the spectacle of a black death? What does it mean for me, a white woman, to listen to that narrative or read a transcription, knowing that I will never be called upon to narrate the death of my loved one while it is happening, and then to write of it, to narrate it to you?

To feel emotionally impacted by an image of another person, Kaja Silverman argues, is to imaginatively project oneself into the visual field. This identification for Silverman can be fractured, multiplied and redirected in ways that richly expand the parameters of ethical life; but at base, one must be able to project oneself into the image.

still image from Diamond Reynold’s live video feed of Jeronimo Yanez’s shooting of her boyfriend, Philando Castile, Cropping/blurring by JS, SO!

In contrast, testimony is to assert that some juridical order has been perverted for an individual and to seek adjudication. But it is also to critique the boundaries of public life: it is to insist that to listen to or receive a narrative is to recognize an another who is not—and could never be—you. To recognize another is to affirm the singularity of the other’s life, a life that has been or can be lost or brutalized. Identification cannot be the sole ground of political action around unjust death: one must be able to say to oneself, “that was not me; that could not have been me; someone singular has been lost; I am troubled nonetheless.”

In Scenes of Subjection, Saidiya Hartman shows how 19th century white abolitionist sentiment was first organized by the spectacle of the black body in pain. White abolitionists often recounted the feeling of “what if that were me?” or “what if that were my family?” Hartman shows how the black body in American life takes on what she calls “fungible” form. If as a commodity, that body must be exchanged, then as spectacle, that body must also be a projective screen for identification where the white viewer emplaces him or herself in order to feel sympathy or outrage. Such sentiment, Hartman insists, is merely feeling for oneself.

Much of the recent discourse surrounding viral videos of black death has concerned looking or “not looking,” or what Alexandra Juhasz calls in a recent essay on her decision not to watch Reynolds’s video, “surfeit images.” But these are not simply images—they are narratives and testimonies. Later in this post, I return to what it means to speak of a “voices” in this context—some of them written and some of them mediated by retelling.

***

Diamond Reynolds narrating after her camera falls, Instagram screen capture by author

A long history of black women’s acts of testimony is occluded in the emphasis on the newness of the new media event and the “convergence” it affords. As Juhasz notes, new media scholar Henry Jenkins describes convergence as the spreading of media events across mediums and formats. Juhasz felt “compelled to join the fray of discourse that surrounds, reproduces and amplifies the video I have not yet seen.” She describes the sense of “knowing” the video without watching because of its convergence across platforms as well as its historical repetition. But convergence is, in the term long afforded by literary discourse, a narrative. Reynolds told the story in real time; one person may have watched the video, in full or in fragments, and told the story of the event in a status update, in conversation, or in a text message. The convergence relates Reynolds’s live stream to a long history of testimony, testifyin’(g), and unofficial or counter-history that has long been held by both oral and print culture across the black diaspora. It is how one “knows” in advance that Castile’s death is “like” so many others before him.

But this advance sense of “knowing” overleaps the singular voice that mediated the video of a singular death. To feel oneself to know in advance is to have internalized, but then occluded, the other. I say this because convergence is premised upon fungibility. Reynolds’s narrating voice is “like” many voices before hers; she occupies a place in a long historical field. At the same time, the singular always interrupts fungibility as an untenable ground of ethical life. Quite simply, the choice is as follows: you can avert your gaze and still participate in public outrage, but you’re missing something important if you don’t listen or attend to narrative, if you don’t amplify its particular domain.

When Reynolds narrated what was happening in the car at that moment—when that narrative is again repeated by people who watched or read of it, as I am now—an alternate and urgent relation is demanded by the narrating voice: neither projection nor identification, but recognition. In this post, I want to explore how this is the case. I will bring to the discussion my understanding of what has long been a concern in American literary studies, one that corresponds to the entry of black women into American literature and public discourse: testimony. Under what conditions have black women been called upon to testify and how does this kind of testimony get mediated?

Image by Flickr User Johnny Silvercloud, Taken 15 November 2015, (CC BY-SA 2.0)

***

On September 24, 2016, the New York Times released a cellphone video of the death of Keith Lamont Scott in Charlotte, North Carolina. Police shot Lamont outside of his car. The police claimed–and continue to claim–that he was holding a gun. Several videos from different vantage points have emerged since Lamont’s death. The presentation of videos mainly confirms a contemporary epistemic and ethical relationship to the visual, a new twist on an old sensory formation that continues to organize American social and political life. Repeatedly, people express a hope, or the belief, that some angle or some vantage correctly adjoined to another angle alone will answer the questions of “what happened?”

President Obama has called for more body cams for police, the underlying logic being that, if recorded, police brutality will become more preventable as it becomes more officially visible. However, the issue remains that the relationship to visual evidence always-already concerns the racist optic that organizes the black male body for a white gaze in advance as “threat.” Judith Butler, writing in 1993 of the Rodney King trial in the essay “Endangered/Endangering: Schematic Racism and White Paranoia” in the Reading Rodney King/Reading Urban Uprising anthology, reminds us that “The visual field is not neutral to the question of race; it is itself a racial formation, an episteme” (17).

This post does not focus on the urgent question of how white supremacy has historically marshaled the black male body within the racialized regime of the visible. Ta-Nehisi Coates and Jackie Wang are among those who have provided recent and pivotal accounts that orient me as I write.

Instead, I want to shift our contemporary conversation about white supremacy, racist policing, and black life and death by addressing the ethical place of black women’s voices as they narrate the spectacle of black death. The question is not, can black death be seen within a white optic? I think the answer is no, it cannot. Time and again, the amassment of images insists that no amount of video footage can or will change the optic. Race is no doubt a visible artifact.

Can hearing differently augment and change its regime?

Jennifer Stoever has recently asked after “the sonic color line” as a rejoinder to W.E.B. Du Bois’s 1903 insistence in The Souls of Black Folk that the “problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line” (3). The problem of a line or threshold suggests the possibility of crossing and, with it, amalgamation. For Du Bois, the need and demand for crossing moves in one direction: the white consciousness should experience, not what it is to live as a black consciousness, but that her own consciousness, indeed very life, is inextricably bound to the other it repudiates. For Du Bois, this transformation–even in the act of writing—was intimately linked to song and narrative. Stoever reminds us that, though writing, he implored his reader to “hear” him.

As I sifted through the news in the weeks following Scott’s death, I kept returning to this question: what does it mean for the voices of black women to become politically audible and intelligible as narrators in a society that still insists on identification as the only ground for ethical life? At the same time, what does it mean for a black woman to become a voice for another, to survive a death and tell the story where another cannot?

NYC action in solidarity with Ferguson. Mo, encouraging a boycott of Black Friday Consumerism. Image by Flickr User The All Nite Images, (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The majority of the police brutality that has received widespread public scrutiny is the visible violence against black males. As the #sayhername hashtag was meant to illustrate, black women are more invisible as subjects of racist violence. When Castile was bleeding out in silence, Reynolds took the camera and became his voice for him. The ground was suddenly shifted away from the visibility, toward audibility. I include within its matrix the significance of Sandra Bland who, using her phone’s video camera, orally narrated her own arrest in her own voice.

In the U.S., white supremacy has attempted to make black voices historically inaudible as historical agents: slaves (not being citizens) were not originally allowed to testify in court, and even after Emancipation, black litigants could not testify against whites in some states. The demand for extra-juridical testimony has remained constant since slavery and Emancipation and it was the first point of entry for black writers into American literature. But the task of testimony—and making it “heard” in a manner of speaking—has long fallen disproportionally on black women, but this task brings to black women, as I will describe, an important power and ethical charge.

Ida B. Wells, 1893, Courtesy of the US National Portrait Gallery

In 1895, Ida B. Wells wrote A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States. The pamphlet provides statistics (the number of lynchings listed under year and purported crimes), but also narratives of specific events. In the Preface by Frederick Douglass, he writes, “I have spoken, but my word is feeble in comparison. You give us what you know and testify from actual knowledge.” She tells one story of a lynch mob coming to a house where a black man accused of a crime was being held while still with his family. As you read, I want to ask “where” Wells is as a speaker is and by what authority:

…that night, about 8 o’clock, a party of perhaps twelve or fifteen men, a number of whom were known to the guards, came to the house and told the Negro guards they would take care of the prisoners now, and for them to leave; as they did not obey at once they were persuaded to leave with words that did not admit of delay.

The woman began to cry and said, “You intend to kill us to get our money.” They told her to hush (she was heavy with child and had a child at her breast) as they intended to give her a nice present. The guards heard no more, but hastened to a Negro church near by and urged the preacher to go up and stop the mob. A few minutes after, the shooting began, perhaps about forty shots being fired. The white men then left rapidly and the Negroes went to the house. Hamp Biscoe and his wife were killed, the baby had a slight wound across the upper lip; the boy was still alive and lived until after midnight, talking rationally and telling who did the shooting.

He said when they came in and shot his father, he attempted to run out of doors and a young man shot him in the bowels and that he fell. He saw another man shoot his mother and a taller young man, whom he did not know, shoot his father. After they had killed them, the young man who had shot his mother pulled off her stockings and took $220 in currency that she had hid there. The men then came to the door where the boy was lying and one of them turned him over and put his pistol to his breast and shot him again. This is the story the dying boy told as near as I can get it.

Here, testimony is not to tell what happened to Wells herself, but to tell the story where the young boy cannot.

Is this narrative’s ethical stance premised upon identification and fungibility? No, I think not. But it is premised upon self-absencing. Using the strategies of direct discourse and shifts in narrative voice (or the subject of the verb’s mode of action), she absents herself as an “I” or first-person to mediate the story—until the very end: “This is the story the dying boy told as near as I can get to it.” Her written tactics are vivid, and a reader perhaps imagines a scene. But the culmination of the image insistently returns to a voice: the dying boy’s. It is only at the end of the synthetic narrative that she attributes the narrative to him as its witness. She writes in the third-person of an event she did not witness: she has allowed her voice to move around in space – from the site where the warrant was made, to the threshold of the family’s cabin door, on the other side of the door, to the anonymous spaces of rumor, then away from the scene to the church, and back.

I’m reminded of a recently audio performance, The Numbers Station [Red Record], where sound artists Mendi + Keith Obadike sonifed Wells’s statistics, using them as numbers to generate audio frequencies (some of the numbers being below 20 hz, the lowest threshold of human hearing).

In a measured and restrained, yet breathy and resonant tone of voice, Mendi Obadike reads the statistics as Keith Obadike generates and oscillates corresponding tones. It is a study in repetition, as is Wells’s pamphlet (racist crime, Douglass writes, “has power to reproduce itself”). And yet, both the pamphlet and the Obadikes’ performance are a study in the singular: one female voice carries each of the numbers in their signification.

Numbers Station is depleted or exhausted narrative space that asks that no images be conjured. The vocal style is impersonal, to be sure—the performer does not passionately react to the numbers. And yet, it is style that moves the voice into that region of the throat where Roland Barthes found the “grain,” where timbre most resonates. It burrows in the human capacity for timbre as the singularity of every voice that says, “here I am.”

When Roland Barthes asked the famous question, “who speaks?” in “The Death of the Author,” he delighted in the impersonal domain of the literary, wherein writing becomes “an oblique space” no longer tied to the physical voice of the body writing. We can say that a physical guarantee of white life, its freedom of continuation underwrites the death of the author. In other words, one can die into text, relinquish the tie that binds the first-person to the body writing, and survive those deaths. It was not important for Barthes to ask, “who may die?,” as in who might have the freedom of impersonality, and “who hears?”, as in who has the right to determine the meaning of the utterances. I want to address these questions.

***

Video technology means that one can record sound and image simultaneously–video having built in mics–yet cell technology makes video, as sound and image, even more accessible and disseminable. Often, the voices of those holding the cell phone at a distance are also captured, remarking upon what they are witnessing or trying to cognize, or they are simply breathing; these voices become a part of the narrative scene. Cell phone technology enables a new mode of witnessing, one connected to older antecedent technologies: the written word as a form of “voice” for black writers. Yet, there is something even more importantly material that gets lost when one focuses on the image of brutality rather than the narrative agency that can be harnessed by the act of recording. In the case of Reynolds’s video, this narrating is explicit. She puts into words what she is seeing. But this narrating can also be more implicit.

Facebook picture of Rakeyia Scott and Keith Lamont Scott

The video released by the New York Times of the police shooting of Keith Lamont Scott included the subtitle, as an introductory slide, that “It was recorded by his wife, Rakeyia Scott.” I pressed pause and, like Juhasz, felt myself unable to watch, stopped in my tracks by this matter-of-fact annotation. Scott had had to videotape the murder of her husband. It took some time before I could return to the video itself, but immediately my thoughts return to Reynolds—again, a black woman had been thrust into the position of narrating black death at the hands of a white police officer, while it was unfolding. But I want to insist that the fungible quality is ethically augmented by narrating itself.

In what follows, New York Times reporters Richard Fausset and Yamiche Alcindor transcribe Scott’s audio and summarize the visuals of the video rather than calling upon readers to view or re-view the video itself. I am choosing to provide the summary report—a narrative—in order to underscore the types of social and sensory positions that get taken up when one tells a story (in this case, it is a narrative of a narrative, since Rakeyia Scott is already positioned in the video as its participant-narrator). This account is not “what happened”—it is a narrative that tries to synthesize audio-visual information into a narrative form. If I also choose to repeat the narrative, rather than the video, it is in alignment with Hartman’s ethical insistence that to repeat the spectacle of death is to reify it, as when she choose not to quote Douglass’ narrative of witnessing the beating of his Aunt Hester in the introduction to Scenes of Subjection. Fred Moten, in In the Break, rightly suggests in response that to turn away from an image is still to be caught up in its imaginary reproduction.

I want the reader to focus on how the Times’s narrative conjures the scene while also involving certain decisions about what sensory data to include as internal to the logical order of events, harnessing adjectives, adverbs, and certain sensorial details. It is one platform of convergence:

Immediately, Ms. Scott said, “Don’t shoot him,” and began walking closer to the officers and Mr. Scott’s vehicle. “Don’t shoot him. He has no weapon. He has no weapon. Don’t shoot him.”

An officer can then be heard yelling: “Gun. Gun. Drop the gun.” A police S.U.V. with lights flashing arrived, partly obscuring Ms. Scott’s view, and a uniformed officer got out. From that point, there are five officers, most of whom appeared to be wearing body armor over plain clothes, around Mr. Scott.

“Don’t shoot him, don’t shoot him,” Ms. Scott pleaded, her voice becoming louder and more anxious. “He didn’t do anything.”

Officers continued to yell “drop the gun” or some variation of it — at least 12 times in 38 seconds.

“He doesn’t have a gun,” Ms. Scott said. “He has a T.B.I.” — an abbreviation for a traumatic brain injury the lawyers said Mr. Scott sustained in a motorcycle accident in November. “He’s not going to do anything to you guys. He just took his medicine.”

“Drop the gun,” an officer screamed again as Ms. Scott tried to explain her husband’s condition. The officer then said he needed to get a baton.

“Keith don’t let them break the windows. Come on out the car,” Ms. Scott said, as the video showed an officer approaching Mr. Scott’s vehicle.

“Drop the gun,” an officer shouted again.

Ms. Scott yelled several times for her husband to “get out the car,” but on the video, he cannot be seen through the window of the S.U.V.

still image from Rakeyia Scott’s video of the police shooting of her husband, Keith Lamont Scott. Cropping/blurring by JS, SO!

The above summary reproduces on the page how Scott’s speaking voice suddenly thrust her into a position of addressing several auditors. In listening to the video, I can hear that she modifies her tone of voice to communicate to each addressee, speaking alternately in an imitate imploring tone to her husband and with sharper emphasis to the police. The tone of voice is also linguistic—the diction changes as the addressee changes (“Come on out the car” is so intimate and familiar to my ear somehow, a private grammar and tone suddenly thrown into the public space). She calls the police, “you guys,” which strikes me as an attempt to tone them down, as it were, to bring them back into a human sphere from which they’d removed themselves. “Ms. Scott tried to explain her husband’s condition”—I add this emphasis, because I think the journalist is channeling here the ways in which Rakeyia Scott is not being heard.

In narrating the scene of her husband’s death, Rakeyia Scott becomes the absolute tie between that past of the image and the present of watching; I use the present tense, because it happens again, with each telling. Scott speaks, more silently and spectrally, to the audiences that will later watch and listen to the video she is recording, or read the transcript as synthesized by journalists or other viewers. In holding the camera, she imputes to herself a third voice as narrator, as did Wells in narrating the scene in A Red Record. This third voice, I am suggesting, is inaudible. It hovers next to her words with new force because, in the act of recording itself, she is testifying, offering a synthetic view as to reality. She creates a hearing space even though it is being foreclosed around her.

She is the only party in the scene who speaks to all addressees at once: her husband, the police, and “us.” The police do not respond to her directly, as if she not there. Indeed, she is standing somewhere outside of the scene as would a narrator. Because Rakeyia Scott holds a camera–outside of the frame–while also speaking, something of testimony gets activated. She has one foot outside of the event in the future after the video. She courageously separates herself from what is unfolding in order to constitute a narrative of the event; she mediates the scene. She not only puts into words facts that are not visible to the police, she issues pleas, commands, and words that carry the explanatory force of narrative, but also testimonial force because she holds the recording device.

still from the NYT‘s publication of Rakeyia Scott’s video of the police murder of her husband, Keith Lamont Scott

By holding a camera, Scott directs her words not only to police, but toward a yet-to-be constituted audience. The recording device also activates the presence of a juridical gaze. She anticipates having to bring this event, not yet fully unfolded, before a court of law. But at the same time, her use of the recording device reveals the juridical sensorium as white. The device’s presence indicates that, were Scott to remember and tell the story later in a court of law, her words on their own would not be enough to guarantee their explanatory power. The spectacle of black death cannot, on its own, announce its own truth within a racist optic. She says what the police (and a spectral jurist) refuse to see. She is forced to narrate because her voice is negated by the police, but also for those unknown viewers who will see this later.

still from the NYT’s publication of Rakeyia Scott’s video of the police murder of her husband, Keith Lamont Scott

There is hope, no doubt, that sometime after this scene has come to end, the video will find a place in the civic as a force of enacting law and justice, and above all, change.

At the turn of the last century, Du Bois wrote of “double consciousness” in The Souls of Black Folk, or the split incumbent upon black American consciousness to see oneself and then, to see oneself as the other sees you, “measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” However, in narrating her husband’s death at the hands of American police in 2016, Rakeyia Scott was split in ways that are not fully compassed by double consciousness. This split into three (or more) not only marks the mediating place of black women in the spectacle of black death, but marks another ethical horizon where at issue is not only seeing differently, but hearing differently. As I’ve tried to describe, these ways of hearing are not an identification with (like me), but a recognition of (you are singular).

This is not yet to speak to the collapse of Scott’s voice after her husband’s murder. Continually occupying this position of testifying, Scott bravely maintains her hold on the camera, even when it means capturing her own screams when Charlotte police begin to shoot. She is both forms. Even then, in screaming, her voice retains its narrative power. Horrifyingly, she cannot change the sequence of events. But her voice continues to exist in belated relation to the scene and to the political afterlife of the murder as image.

With the digital, it becomes possible to reduce the space and time of testimony. With Reynolds, many watched on Facebook Live an event they were powerless to change in its unfolding. With Scott, the police gun shots had not yet taken place. I think the question is, were Rakeyia Scott white, would her words have been pro-active testimony of a not-yet determined event? Her words would have been lent a different power, a power to change events in their unfolding. In America, white testimony and black testimony bear fundamentally different ontological weight.

still from the NYT‘s publication of Rakeyia Scott’s video of the police murder of her husband, Keith Lamont Scott

In repeatedly trying to answer the question whose recurrence haunts me–What does it mean for Scott to have narrated the murder and death of her loved one as it was taking place?–I am thrust up against the sense that we are in a new ethical moment and relation to history when it becomes possible—and necessary—for black women to narrate death to an unknown public as it is unfolding. This includes the moments before their own deaths, such as Korryn Gaines, who was killed by the Baltimore County Police Department in August 2016, in her own apartment while holding her five year old son, who watched and himself suffered a gunshot wound. Like Reynolds, she broadcast her recordings via Facebook live.

Testimony is usually reserved for some time after the scene, and its hallmark is that it is belated. It must reconstitute a scene we can no longer see. The burden is on the narrating voice to conjure, with persuasion and conviction, the truth of the missing image, so that the story can in fact stand in place of the scene, merging with it on an ontological level. The live streamed video fundamentally reduces that distance in time, where the narrative now overlays the image, not from outside of it, but within it. They refuse the false juridical narratives that will, in the future, attempt to reframe the image in the name of “fact.”

In the differentiation of the senses, there is the order of the visible and the order of narrating voice that accompanies the image to give it sense, to retell its meaning somehow after. Scott insists on being there to narrate. That is not to suggest that somehow, because Scott speaks, she is more “present.” While the video is meant as future evidence, it also lends a voice of recognition in this ethical sense I have been trying to describe. Scott’s voice is split by the camera. Even if she herself were not to have survived the event, in narrating and taping, she becomes the medium for history (the persistent and unchanging fact of unjust black death). And yet, she is the vehicle for this death that matters in its singularity. She speaks as both, as history and particularity.

In watching and listening, I finally understand something of Hannah Arendt’s argument in The Human Condition that speech and action form a fundamental unit. For Arendt, great deeds cannot happen in silence: they must be narrated and accompanied by speech. And yet the scenes Arendt describes couldn’t be more different. This raises the issue of the conditions of narration: it is one thing to be speaking to your fellow citizens in a sanctioned forum. It is another to hold a camera as an officer holds a gun that might very well shoot you too.

Alicia Garza, one of the three co-founders of the national #blacklivesmatter movement in 2013, along with Opal Tometi and Patrisse Cullors.

What I’d like to preserve about Arendt’s analytic is the union of speech and action. It is related to the role of the right to speak in the ancient polis, where one had to take responsibility for the possibility that one’s speech might lead to the deeds of the community. But speech, for Arendt, is the function of action that makes it for others, that commits that action to the memories of others who can narrate it. In Arendt’s view, the story does not end there. The fact is, one might not survive one’s greatest deed. If one does survive, it would be in highly transformed terms. It is for others to tell the story.

In part, the ethical bond means our lives are in each other’s hands, that the other is responsible for narrating where you cannot. We are always-already ethically bound as “witnesses and participants,” as Frederick Douglass once described himself in his 1851 Narrative. He remembers himself as a six year old child not only watching, but listening to the scene of brutality against his Aunt Hester that he later recalls and transmutes into a narrative.

My hope is that this power of narrative is in the midst of opening another political horizon. It refutes identification as the untenable ground of ethics and action. We must act—or hold on to a sense of acting, even if its meaning and parameters remain unclear. As I reach the end of this essay, I can’t shake the sense that that it is not enough to have provided an analytic for understanding these videos and their voices in their long resonance with history. Nor does it feel right to say that these videos “do” something for us– they, and their narrators, demand that we do something for them. This mode of action begins in the attitude of hearing. Hearing testimony, Jill Stauffer describes in Ethical Loneliness: The Injustice of Not Being Heard, means allowing the unchangeable past to resound in the present. Only then can one “author conditions where repair is possible” (4).

It might be, then, that hearing itself is a mode of action, even if that action be much delayed. Hearing becomes action when formal power structures have denied its event as a source of repair. As listeners to the present and the past, we are neither projecting ourselves in the images nor imagining ourselves uninvolved in their scenes of subjection. We were all already there. And yet, to be “there” means to allow oneself to be exposed to another’s singular experience, rather than favor a collectively conditioned idea of what is known in advance. Who and where will we be afterward, is what remains. These videos and their not-yet determined afterlives become louder than the optic, if not in the word than in the sounds.

—

I’d like to thank Jennifer Stoever, Erica Levin, Jay Bernstein, and Ben Williams for their thoughtful voices and contributions that resound throughout this essay.

—

Julie Beth Napolin is Assistant Professor of Literary Studies at The New School, a musician, and radio producer. She received a PhD in Rhetoric from the University of California, Berkeley. Her work participates in the fields of sound studies, literary modernism and aesthetic philosophy, asking what practices and philosophies of listening can tell us about the novel as form. She served as Associate Editor of Digital Yoknapatawpha and is writing a book manuscript on listening, race, and memory in the works of Conrad, Du Bois, and Faulkner titled The Fact of Resonance. Her work has appeared in qui parle, Fifty Years After Faulkner (ed. Jay Watson and Ann Abadie), and Vibratory Modernism (ed. Shelley Trower and Anthony Enns).

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“A Sinister Resonance”: Joseph Conrad’s Malay Ear and Auditory Cultural Studies–Julie Beth Napolin

SANDRA BLAND: #SayHerName Loud or Not at All–Regina Bradley

On Whiteness and Sound Studies–Gus Stadler

Spaces of Sounds: The Peoples of the African Diaspora and Protest in the United States–Vanessa K. Valdés

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- SO! Reads: Alexis McGee’s From Blues To Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics

- SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

- Impaulsive: Bro-casting Trump, Part I

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments