SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests (Penn State University Press) is a book “about the sounds made by those seeking change” (5). It situates these sounds within a broader inquiry into rhetoric as sonic event and sonic action—forms of practice that are collective, embodied, and necessarily relational. It also addresses a long-standing question shared by many of us in rhetorical studies: Where did the sound go? And specifically, in a field that had centered at least half of its disciplinary identity around the oral/aural phenomena of speech, why did the study of sound and rhetoric require the rise of sound studies as a distinct field before it could regain traction?

Eckstein confronts this silence with urgency and clarity, offering a compelling case for how sound operates not just as a sensory experience but as a rhetorical force in public life. By analyzing protest environments where sound is both a tactic and a terrain of struggle, Sound Tactics reinvigorates our understanding of rhetoric’s embodied, affective, and spatial dimensions. What’s more, it serves as an important reminder that sound has always played an important role in studies of speech communication.

Rhetoric emerged in the Western tradition as the study and practice of persuasive speech. From Aristotle through his Greek predecessors and Roman successors, theorists recognized that democratic life required not just the ability to speak, but the ability to persuade. They developed taxonomies of effective strategies—structures, tropes, stylistic devices, and techniques—that citizens were expected to master if they hoped to argue convincingly in court, deliberate in the assembly, or perform in ceremonial life.

We’ve inherited this rhetorical tradition, though, as Eckstein notes early in Sound Tactics, in the academy it eventually splintered into two fields: one that continued to study rhetoric as speech, and another that focused on rhetoric as a writing practice. But somewhere along the way, even rhetoricians with a primary interest in speech moved toward textual representation of speech, rather than the embodied, oral/aural, sonic event that make up speech acts (see pgs 49-50).

Sound Tactics corrects this oversight first by broadening what counts as a “speech act”—not only individual enunciations, but also collective, coordinated noise. Eckstein then offers updated terminology and analytical tools for studying a wide range of sonic rhetorics. The book presents three chapter-length case studies that demonstrate these tools in action.

The first examines the digital soundbite or “cut-out” from X González’s protest speech following the school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. The second focuses on the rhythmic, call-and-response “heckling” by HU Resist during their occupation of a Howard University building in protest of a financial aid scandal. The third analyzes the noisy “Casseroles” retaliatory protests in Québec, where demonstrators banged pots and pans in response to Bill 78’s attempts to curtail public protest.

A full recounting of the book’s case studies isn’t possible here, but they are worth highlighting—not only for the issues Eckstein brings to light, but for how clearly they showcase his analytical tools and methods in action. These methods, in my estimation, are the book’s most significant contribution to rhetorical studies and to scholars more broadly interested in sound analysis.

Eckstein’s analytical focus is on what he calls the “sound tactic,” which is “the sound (adjective) use of sound (noun) in the act of demanding” (2). Soundness in this double sense is both effective and affective at the sensory level. It is rhetoric that both does and is sound work—and soundness can only be so within a particular social context. For Eckstein, soundness is “a holistic assessment of whether an argument is good or good for something” (14). Sound tactics, then, utilize a carefully curated set of rhetorical tools to accomplish specific argumentative ends within a particular social collective or audience capable of phronesis or sound practical judgement (16). Unsound tactics occur when sound ceases to resonate due to social disconnection and breakage within a sonic pathway (see Eckstein’s conclusion, where he analyzes Canadian COVID-19 protests that began with long-haul truck drivers, but lost soundness once it was detached from its original context and co-opted by the far right).

Just as rhetorical studies has benefitted from the influence of sound studies, Eckstein brings rhetorical methods to sound studies. He argues that rhetoric offers a grounding corrective to what he calls “the universalization of technical reason” or “the tendency to focus on the what for so long that we forget to attend to the why” (29). Following Robin James’s The Sonic Episteme: Acoustic Resonance, Neoliberalism, and Biopolitics, he argues that sound studies work can objectify and thus reify sound qua sound, whereas rhetoric’s speaker/audience orientation instead foregrounds sound as crafted composition—shaped by circumstance, structured by power, and animated by human agency. Eckstein finds in sound studies the terminology for such work, drawing together terms such as acousmatics, waveform, immediacy, immersion, and intensity to aid his rhetorical approach. Each name an aspect of the sonic ecology.

Rhetoricians often speak of the “rhetorical situation” or the circumstances that create the opportunity or exigence for rhetorical action and help to define the relationship between rhetor and audience. While the rhetorical action itself is typically concrete and recognizable, the situation itself—which is always in motion—is more difficult to pin down. “Acousmatics” names a similar phenomenon within a sonic landscape. Noise becomes signal as auditors recognize and respond to particular kinds of sound—a process that requires cultural knowledge, attention, and the proverbial ear to hear. A sound’s origins within that situation may be difficult to parse. Acousmastics accounts for sound’s situatedness (or situation-ness) within a diffuse media landscape where listeners discern signal-through-noise, and bring it together causally as a sound body, giving it shape, direction, and purchase. As such a “sound body” has a presence and power that a single auditor may not possess.

Eckstein defines “sound body” as “our imaginative response to auditory cues, painting vivid, often meaningful narratives when the source remains unseen or unknown” (10). And while the sound body is “unbounded,” it “conveys the immediacy, proximity, and urgency typically associated with a physical presence (12). Thus, a sound body (unlike the human bodies it contains) is unseen, but nonetheless contained within rhetorical situations, constitutive of the ways that power, agency, and constraint are distributed within a given rhetorical context. Eckstein’s sound body is thus distinct from recent work exploring the “vocal body” by Dolores Inés Casillas, Sebastian Ferrada, and Sara Hinojos in “The ‘Accent’ on Modern Family: Listening to Vocal Representations of the Latina Body” (2018, 63), though it might be nuanced and extended through engagement with the latter. A focus on the vocal body brings renewed attention to the materialities of the voice—“a person’s speech, such as perceived accent(s), intonation, speaking volume, and word choice” and thus to sonic elements of race, gender, and sexuality. These elements might have been more explicitly addressed and explored in Eckstein’s case studies.

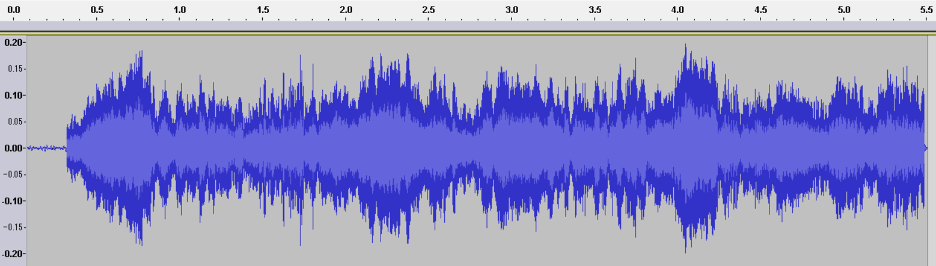

Eckstein uses these terms to help us understand the rhetorical complexities of social movements in our contemporary, digital world—movements that extend beyond the traditional public square into the diverse forms of activism made possible by the digital’s multiplicities. In that framework he offers the “waveform” as a guiding theoretical concept, useful for discerning the sound tactics of social movements. A waveform—the digital, visual representation of a sonic artifact—provides a model for understanding how sound takes shape, circulates, and exerts force. Waveforms also obscure a sound’s originating source and thus act acousmastically.

“[A] waveform is a visual representation of sound that measures vibration along three coordinates: amplitude, frequency, and time” (50). Eckstein draws on the waveform’s “crystallization” of a sonic moment as a metaphor to show sound’s transportability, reproducibility, and flexibility as a media object, and then develops a set of analytical tools for rhetorical analysis that match these coordinates: immediacy, immersion, and intensity. As he describes:

Immediacy involves the relationship between the time of a vibration’s start and end. In any perception of sound, there can be many different sounds starting and stopping, giving the potential for many other points of identification. Immersion encompasses vibration’s capacity to reverberate in space and impart a temporal signature that helps locate someone in an area; think of the difference between an echo in a canyon and the roar of a crowd when you’re in a stadium. Finally, intensity describes the pressure put on a listener to act. Intensity provides the feelings that underwrite the force to compel another to act. Each of these features and the corresponding impact of this experience offer rhetorical intervention potential for social movements. (51)

This toolset is, in my estimation, the book’s most cogent contribution for those working with or interested in sonic rhetorics. Eckstein’s case studies—which elucidate moments of resistance to both broad and incidental social problems—offer clear examples of how these interrelated aspects of the waveform might be brought to bear in the analysis of sound when utilized in both individual and collective acts of social resistance.

To highlight just one example from Eckstein’s three detailed case studies, consider the rhetorical use of immediacy in the chapter titled “The Cut-Out and the Parkland Kid.” The analysis centers on a speech delivered by X González, a survivor of the February 14, 2018, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida. Speaking at a gun control rally in Ft. Lauderdale six weeks after the tragedy, González employed the “cut-out,” a sound tactic that punctuated their testimony with silence.

Embed from Getty Images.

As the final speaker, González reflected on the students lost that day—students who would no longer know the day-to-day pleasures of friendship, education, and the promise of adulthood. The “cut-out” came directly after these remembrances: an extended silence that unsettled the expectations of a live audience disrupting the immediacy of such an event. As the crowd sat waiting, González remained resolute until finally breaking the silence: “Since the time that I came out here, it has been six minutes and twenty seconds […] The shooter has ceased shooting and will soon abandon his rifle, blend in with the students as they escape, and walk free for an hour before arrest” (69–70).

As Eckstein explains, González “needed a way to express how terrifying it was to hide while not knowing what was happening to their friends during a school shooting” (61). By timing the silence to match the duration of the shooting, the focus shifted from the speech itself to an embodied sense of time—an imaginary waveform of sorts that placed the audience inside the terror through what Eckstein calls “durational immediacy.” In this way, silence operated as a medium of memory, binding audience and victims together through shared exposure to the horrors wrought over a short period of time.

…

Sound Tactics is a must-read for those interested in a better understanding of sound’s rhetorical power—and especially how sonic means aid social movements. In conclusion, I would mention one minor limitation of Eckstein’s approach. As much as I appreciated his acknowledgement of sound’s absence from the Communication side of rhetoric, such a proclamation might have benefited from a more careful accounting of sound-related works in rhetorical studies writ large over the last few decades. Without that fuller context, readers may conclude that rhetorical studies has—with a few exceptions—not been engaged with sound. To be fair, the space and focus of Sound Tactics likely did not permit an extended literature review. There is thus an opportunity here to connect Eckstein’s important intervention with the work of other rhetoricians who have also been advancing sound studies.

I am including here a link to a robust (if incomplete) bibliography of sound-related scholarship that I and several colleagues have been compiling, one that reaches across Communication and Writing disciplines and beyond.

—

Featured Image: Family at the CLASSE (Coalition large de l’ASSÉ ) Demonstration in Montreal, Day 111 in 2012 by Flicker User scottmontreal CC BY-NC 2.0

—

Jonathan W. Stone is Associate Professor of Writing and Rhetoric at the University of Utah, where he also serves as Director of First-Year Writing. Stone studies writing and rhetoric as emergent from—and constitutive of—the mythologies that accompany notions of technological advance, with particular attention to sensory experience. His current research examines how the persisting mythos of the American Southwest shapes contemporary and historical efforts related to environmental protection, Indigenous sovereignty, and racial justice, with a focus on how these dynamics are felt, heard, and lived. This work informs a book project in progress, tentatively titled A Sense of Home.

Stone has long been engaged in research that theorizes the rhetorical affordances of sound. He has published on recorded sound’s influence in historical, cultural, and vernacular contexts, including folksongs, popular music, religious podcasts, and radio programs. His open-source, NEH-supported book, Listening to the Lomax Archive, was published in 2021 by the University of Michigan Press and investigates the sonic archive John and Alan Lomax created for the Library of Congress during the Great Depression. Stone is also co-editor, with Steph Ceraso, of the forthcoming collection Sensory Rhetorics: Sensation, Persuasion, and the Politics of Feeling (Penn State U Press), to be published in January 2026.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings –Vanessa Valdés

Quebec’s #casseroles: on participation, percussion and protest–-Jonathan Sterne

SO! Reads: Steph Ceraso’s Sounding Composition: Multimodal Pedagogies for Embodied Listening-–Airek Beauchamp

Faithful Listening: Notes Toward a Latinx Listening Methodology––Wanda Alarcón, Dolores Inés Casillas, Esther Díaz Martín, Sara Veronica Hinojos, and Cloe Gentile Reyes

The Sounds of Equality: Reciting Resilience, Singing Revolutions–Mukesh Kulriya

SO! Reads: Todd Craig’s “K for the Way”: DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies—DeVaughn Harris

Faithful Listening: Notes Toward a Latinx Listening Methodology

**This piece is co-authored by Wanda Alarcón, Dolores Inés Casillas, Esther Díaz Martín, Sara Veronica Hinojos, and Cloe Gentile Reyes

For weeks, we have been inundated with executive orders (220 at last count), alarming budget cuts (from science and the arts to our national parks), stupendous tariff hikes, the defunding of DEI-anything, the banning of transgender troops, a Congressional renaming of the Gulf of Mexico, terrifying ICE raids, and sadly, a refreshed MAGA constituency with a reinvigorated anti-immigrant public sentiment. Worse, the handlers for the White House’s social media publish sinister MAGA-directed memes, GIFs across their social channels. These reputed Public Service Announcements (PSAs), under President Trump’s second term, ruthlessly go after immigrants.

It’s difficult to refuse to listen despite our best attempts.

“The ASMR video was true.”

On February 18, 2025, the official White House social media account, @WhiteHouse, shared a 40-second video showing a group of detained immigrants boarding a military aircraft for deportation. The video was captioned: “ASMR: Illegal Alien Deportation Flight.” ASMR, or autonomous sensory meridian response, features gentle, soothing sounds—such as whispering, tapping, or brushing—which can evoke pleasurable tingling sensations. In this satirical ASMR-style post, however, the sounds include the clinking of metal shackles on concrete floors, the jangle of handcuffs against bodies, and the grating of metal on metal as detainees slowly ascend the aircraft’s steps. By framing these distressing noises within the ASMR genre, the video invites listeners to consume them as aesthetically pleasing; encouraging a visceral embodiment where the sounds of violence toward migrants elicit an uncontrollable physical pleasure that seeps through the body. This effectively turns state violence into an unsettling sonic spectacle. Cruelty towards migrants, according to Cristina Beltrán, is not a failure of democracy but an expression of it. The (sonic) spectacle of migrant cruelty functions as a political practice meant to sustain white democracy as both a racial and political category.

Framed within ASMR, Trump’s official message is unmistakably “saying the quiet part out loud.” But not all that well. A closer listen reveals that the roar of the jet engine drowns out more intimate, human sounds: footsteps on the tarmac, the rustle of police pat-downs, and the deep, rhythmic breaths—proof of life—condemned. Listening to this disturbing post, we become attuned to our own internal pleads; our refusal to believe until the unsettling truth confirms: this isn’t a parody or a hoax—it’s real.

How does a sonic social media trend—built around such sounds as the crinkling of chip bags, the crunches of eating, the tap-tap of acrylic nails, the gentle clinks of typing or espresso-making—become a soundboard for the forced removal of immigrants? Indeed, the video has amassed nearly 105 million views on X alone. Clearly, the post broadcasts a pedagogy of cruelty—a lesson in how to aestheticize suffering—and we are left questioning just how far that message both travels and resonates. For many, the video is neither entertaining nor soothing, but rather shocking, offensive, and deeply disturbing.

Written comments show more revulsion than support, with many users openly challenging the video. In doing so, their protest, contained in the comments, starts to dismantle the ASMR aesthetic, undercutting its intended sense of calm. After all, the video isn’t particularly convincing as ASMR to begin with! These are echoes of dissent, outrage, and refusal, that accompany the in-person collective actions that have taken place across the nation rallying against Trump’s broader white-supremacist and anti-democratic agenda.

“What was louder was the screaming and cursing inside my head.”

History shows us that abolitionist efforts often relied on the sounds and images of chains to evoke empathy for enslaved Africans—making their suffering and humanity visible to a broader public. Yet, as Saidiya Hartman’s Scenes of Subjection makes clear, such representations can easily devolve into a spectacle of suffering, where the emphasis shifts from the enslaved person to the emotional response of the white witness. Today, that same auditory imagery—clinking metal, mechanical restraints—resurfaces, but in a profoundly different register. No longer stirring empathy, they risk desensitizing listeners to the pain and struggle of Latinx migrants. This ASMR instance, directed at MAGA-listeners, prioritizes a cruel-yet-gleeful response without any compassion whatsoever towards immigrants.

The word “Illegal” in the caption further amplifies the discourse of criminality, evoking a long legacy of racialized policies and media portrayals that cast mexicanos and Chicanos as perpetually deportable. Note the hypocrisy in naming the people as illegal, when their forced removal without legal due process, is itself illegal. U.S. immigration policy—think Operation Wetback and the Bracero Program, have long simultaneously expelled and depended on Mexican labor. The enduring power of these tropes lies not just in law, but in sentiment—in the way migrants are imagined, portrayed, and ultimately policed in the public eye. Just as Hartman argues that the end of slavery did not mean the arrival of true freedom for Black Americans, so too have U.S. immigration policies failed to fully embrace immigrants as residents or neighbors and much less citizens. In both cases, legal status did not equate to genuine belonging or liberation.

What is notable in the current deployment of “illegality” in the @WhiteHouse post is its expanded scope: whereas earlier rhetoric primarily targeted Mexicans and Mexicanness this framing now extends to encompass all Latinx peoples, which always includes Black, Indigenous, Trans and Queer. This further intensifies prior waves of anti-Mexican sentiment while broadening the reach of criminalizing discourse. In doing so, it reinforces a racialized logic of illegality that casts an ever-widening net of suspicion and exclusion.

The MAGA White House’s broader propaganda – from the self-deport ads on Spanish-language media and Kristi Noem’s pinche photo-ops from CECOT (El Salvador’s infamous mega-prison) to SCOTUS attempts to revoke birthright citizenship – raises the stakes of listening, rendering our response—and our work as Latinx sound studies scholars—urgent.

Like it or not, this video reshapes the contours of our field in real time. Using the ASMR video as a point of departure, we offer a mode of listening on the side of resistance—a practice that affirms our solidarity with migrants and their right to move, work, and live with dignity. Drawing on the work of the late María Lugones, we advocate for a practice of faithful witnessing—a listening attuned not only to sound, but to histories, structures, and acts of refusal that resist dehumanization.

Ofrenda

From Lugones’s book Pilgrimages/Peregrinajes: Theorizing Coalition Against Multiple Oppressions, she teaches that a collaborator witnesses from the side of power; a faithful witness stands with resistance even when it entails risk. And, to witness faithfully is to recognize and honor acts of resistance—even when doing so defies common sense of what we recognize as political acts/sounds. In Decolonizing Diasporas, Yomaira Figueroa-Vásquez reminds us of the important coalitional sociality Lugones envisions in practicing faithful witnessing. For Figueroa, “the practice of faithful witnessing is one that oppressed and colonized peoples have deployed since time immemorial as a method of bearing witness to each other’s humanity even as they faced myriad forms of violence” (156).

Faithful witnessing entails centering the plight of all MAGA political scapegoats, migrants in precarity, pro-Palestinian student activists, the still separated children, trans youth, women, and who ever is next on the Project 2025 agenda. Faithful witnessing is not about centering our own emotional response, but about coming together to listen, to bear witness, and to protect. In response to these distorted public signals, we present a suite of countersonics, shared in a lo-fi listening mode that enacts faithful witnessing and affirms our roles as co-resisters to sonic oppression. We conclude with a noise-filled, healing artifact: a sonic limpia for deep listening and a playlist to sustain the good fight.

FOR THE FULL PLAYLIST CLICK THIS LINK, OR START BELOW!

—

Featured Image: Philly Immigrant May 1st, 2025 march for Justicia. Migrant workers and supporters rallied at 4th & Washington and marched in the streets to the AFL-CIO Mayday rally and march. Image by Joe Piette, cropped by SO! CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

—

Wanda Alarcón is an Assistant Professor of Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Arizona. Her research takes up sound as a generative site and method for hearing and amplifying resistant grammars in Chicana narratives. She is currently working on her first book manuscript, Chicana Soundscapes, which listens closely to sound, noise, language, songs, echoes, and silences, and proposes decolonial feminist ways of hearing Chicana and queer Chicana worlds.

Dolores Inés Casillas (she/her/ella) is Director of the Chicano Studies Institute (CSI) and Professor of Chicana and Chicano Studies at UC Santa Barbara. Her research focuses on immigrant engagement with U.S. Spanish-language and bilingual media. She is the author of Sounds of Belonging: U.S. Spanish-language Radio and Public Advocacy (NYU Press, 2014), co-editor of The Companion to Latina/o Media Studies (Routledge Press, 2016) and Feeling It: Language, Race and Affect in Latinx Youth Learning (Routledge Press, 2018).

Esther Díaz Martín (she/her/ella) is an Assistant Professor of Latin American and Latino Studies and Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Illinois Chicago. Her book, Radiophonic Feminisms: Latina Voices in the Digital Age of Broadcasting, (UT Press, 2025) theorizes Chicana feminist listening and attends to the political work of Latina voices in contemporary sound media.

Sara Veronica Hinojos (she/her/ella) is an Assistant Professor of Media Studies at Queens College, CUNY. Her research critically engages popular representations of Chicanxs and Latinxs as racialized, “accented” speakers. Her current book project, The Racial Politics of Chicana and Chicano Linguistic Scripts in Media (1925-2014), intentionally brings together language politics, digital media, humor studies and sound studies.

Cloe Gentile Reyes (she/her/ella) is a queer Boricua scholar, poet, and perreo profa from Miami Beach. She is a Faculty Fellow in NYU’s Department of Music and has a PhD in Musicology from UC Santa Barbara. Her writing focuses on how Indigenous Caribbean femmes navigate intergenerational trauma and healing through decolonial sound, fashion, and dance. Her pieces have been featured in Sounding Out!, Intervenxions, and the womanist magazine, Brown Sugar Lit.

—

Thank you to Daimys Ester García for care in the form of editorial labor.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“Oh how so East L.A.”: The Sound of 80s Flashbacks in Chicana Literature–Wanda Alarcón

Echoes in Transit: Loudly Waiting at the Paso del Norte Border Region–José Manuel Flores & Dolores Inés Casillas

Xicanacimiento, Life-giving Sonics of Critical Consciousness–Esther Díaz Martín and Kristian E. Vasquez

Listening to Digitized “Ratatas” or “No Sabo Kids”–Sara Veronica Hinojos and Eliana Buenrostro

Ronca Realness: Voices that Sound the Sucia Body–Cloe Gentile Reyes

Latinx Soundwave Series–Edited by Dolores Inés Casillas

Recent Comments