The Sound of Hippiesomething, or Drum Circles at #OccupyWallStreet

Last week’s news was been full of alarming stories of real and threatened violence at various #Occupy sites around America. But also disturbing were the reports that complaints about the continuous drumming at the Occupy Wall Street site in Lower Manhattan were threatening to shut the entire operation down. According to stories in N + 1, slate.com, Mother Jones, and New York, the ten hour marathon drum circles at Zuccotti Park have been a focal point of mounting tensions, both between the occupiers and the drummers, and between the occupiers and the community at large. Last week, community members asked that the drummers limit their drumming to 2 hours a day, a request backed by actual OWS protesters. The drummers, loosely organized in a group called PULSE, initially resisted the restriction, claiming that such requests mimicked those of the government they were protesting against. Since then, a compromise has been worked out, but the situation gives rise to a host of questions about race, sound, drums, and protest.

Community organizers both inside and outside OWS said they were distressed by the continuous noise that these protesters are making, and certainly they had reason: as Jon Stewart put it in his episode of talking points, “it’s a public space, it’s for everyone, including people who don’t consider drum circles to be sleepy time music.”

Writer and singer Henry Rollins agrees, telling LA Weekly that he dreams of an #Occupy Music festival, because “So far [he has] heard people playing drums and other percussion instruments” but still wonders “if there will be a band or bands who will be a musical voice to this rapidly growing gathering of citizens.” Rage Against the Machine guitarist and frequent #Occupier Tom Morello also seems to concur, telling Rolling Stone, “Normally protests of this nature are furtive things, It’ll be 12 people with a small drum circle and a couple of red flags. But this has become something that people feel part of.” Stewart, Rollins, and Morello all have a point: not everyone likes drum circles, in fact some people feel quite strongly about them, which has the potential to be divisive for a movement famously representing “the 99%.”

But over and above the questions of musical taste, the very audible presence of snare drums, cymbals, and entire drum sets at OWS—more often found in marching bands or suburban garage band practice spaces than the usual drum circle staple, the conga—raises a different set of questions, both sonic and social, around the interrelated issues of “noise,” public space, and privilege.

That a drum circle populated by a large number of bad, mostly white drummers is being touted as “the sound” of occupation isn’t that surprising, at least not for alumni of UC Berkeley.

In my day, a more conga-oriented drum circle sprouted up on Sproul Plaza every Sunday; today, a similar one occupies a green space in Golden Gate Park right across from Hippie Hill, pretty much 24/7. (I walk by it every Thursday on my way to the gourmet food trucks: happily, the delicious smell of garlic noodles and duck taco obliviates all other senses.)

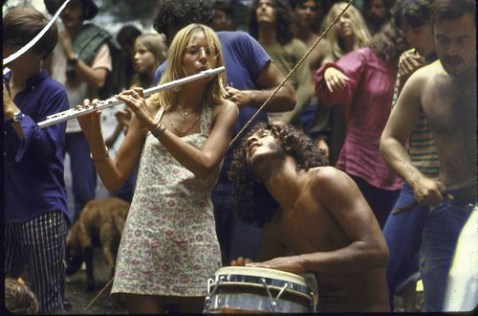

These kinds of regular, yet impromptu, circles abound in California and elsewhere: indeed, the sound of drum circles à la OWS has characterized certain types of social spaces for the last forty years. But what exactly does the sound of drum circles characterize? What meaning is being made by them, and why?

In the Americas, drum circles go back hundreds of years– many indigenous peoples have drumming traditions, for example, and, in Congo Square in New Orleans, slaves of African ancestry gathered weekly to dance to the rhythms they played on the bamboula, a bamboo drum with African origins, beginning in the early 1700s. The notion of the “circle” was a fundamental part of the dancing and music making at Congo Square—according to Gary Donaldson, the circles represented the memories of African nationalities and various reunited tribes people—and was echoed in various types of “ring shouts” across the West Indies and the Southern U.S. The contemporary drum circle stand-by, the conga, also came to the Americas via the forced migration of slaves; it is of Cuban origin but with antecedents in Africa, like the bamboula. The black power movements of the 1960s drew on this history—and sound—to good effect, reigniting semi-permanent drum circles in many U.S. neighborhoods– like the formal gathering that meets in Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem on Saturdays that is currently also under fire from a nearby condo association –audibly announcing their presence and enacting new community formations.

Given this history–and without erasing the presence of drummers of color at OWS--it can seem puzzling how the drum circle has come to occupy such a curiously whitened position in America’s cultural zeitgeist. Furthermore, one of the more problematic aspects of the OWS drum circle debate is the racialized implications of the instrumentation there—implications borne out by videos of OWS that show an overabundance of snares, some of the loudest drums available. According to percussionist Joe Taglieri, “no conga is louder than a fiberglass drum with a synthetic head.” If snares are louder than congas, then noise – actual decibel level — is probably not the sole issue when community groups attempt to control or oust drummers like those in Marcus Garvey Park. It does seem to be a key point of contention at OWS, however.

While there is also a history of African American marching bands, especially in the South, snare drums speak to a different set of American cultural traditions. Drum kits themselves evolved from Vaudeville, when theater space restrictions (and tight pay rolls) precluded inviting a large marching band inside. Mainstream associations with snares include but are not limited to army parades, high school marching bands, and of course hard rock music. Sometimes, like in the case of Tommy Lee, it is an unholy alliance of several of these contexts.

In other words, outside of OWS, snares are hardly the sound of social upheaval.

How the drum circle became associated with political protest in the first place is interesting. Although people sometimes associate drum circles with beatniks rather than hippies, a case could be made that they actually connect more strongly to an electrified Woodstock rather than an acoustic Bleecker Street, thanks in part to Michael Shrieve’s widely mediated turn during Santana’s performance of “Soul Sacrifice” at the 1969 festival.

It is important to note that Shrieve is playing the traps in this sequence, not the conga, which is one reason I’d like to suggest that something about that scene – the hands on the congas, the grins of the other guys, the ecstatic face of a 20-year-old as he slams his kit, and the fetishistic gaze of the camera on the sticks, the skins and the cymbals – caught the imagination of a particular segment of American society. Santana’s band – two Mexican Americans (Carlos Santana and Mike Carabello), a Nicaraguan (Chepito Areas), two whites (Shrieve and Gregg Rolie, who later plagued the world in Journey) and an African American (bassist David Brown)—was truly multi-racial, creating a “small world” visual that furthered Woodstock’s utopian rhetoric in ways that were surely not borne out by the demographics of its audience. More importantly perhaps, the Woodstock movie showed a white suburban hippie guy as an equal participant in a multi-ethnic rhythmic stew, a powerful image in the 1960s. Indeed, the Santana performance may be precisely the moment when the idea of the drum circle was lifted from the context of “black power” and moved into the hippie mainstream.

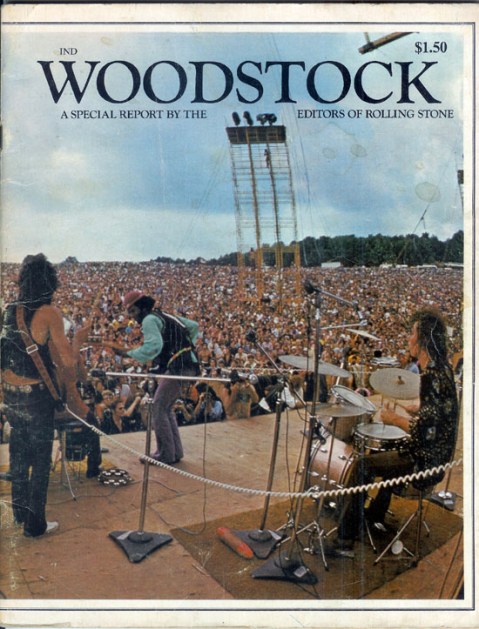

When's the last time you've seen a drummer on a magazine cover?: Santana on Rolling Stone's Woodstock special issue

Woodstock made congas hip to the mass of America—not just in Santana’s set but also in the performances of Richie Havens and Jimi Hendrix—and Woodstock helped define what the drum circle meant, in part by encapsulating certain discursive tropes that were very particular to those times. For example, drum circles epitomize the ’60s idea that political action is simultaneously self-expressive and collective. If a crowd of people sing “We Shall Overcome” or chant “Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh/The NLF is going to win,” it is a a collective act. It’s collective even if the crowd is singing “Yellow Submarine” and it’s not overtly political. By contrast, drum circles are about improvisation, so each drummer can “do his own thing” while participating in the groupthink. (The “his” is implied: video of drum circles show few women participants. Apparently Janet Weiss, Meg White, and Sheila E.’s “own thing” can actually be done on their own.)

In terms of sound, drum circles also project well beyond their immediate location, compared to singing and chanting (in fact, OWS has had problems with the drum circles drowning out its “human microphone”). Plus, since the drummers can take breaks and change out, the actual drumming never stops, unlike a performing musician. Thus, drum circles are celebrations of self expression that are actively imposed on an audience that is well beyond eyesight. This summarizes a modern view of personality rooted in the 1960s: that it’s not enough to participate, you’ve also got to “be yourself.” I think these two notions account for the enduring idea of the drum circle as a supposedly political sound, even when it’s not. Drumming in a drum circle allows for a public display of self-expression that simultaneously allows the participant to belong to a group. The appeal of that is obvious, especially in our contemporary iCulture. However, the politicization of the sound of drum circles only makes sense when you add in the lingering sonic traces of black protest, modulated through a hippie lens. You can see this clearly in New York magazine’s “Bangin’: A Drum Circle Primer” (10.30.11), whose visual imagery prominently features a West African djembe drum and describes only the “hippie-era use of traditional African instruments” rather than their actual, snare-heavy configuration at OWS. Despite the snares and in spite of the oft-commented on lack of black faces at OWS—see Greg Tate’s piece in the Village Voice—drum circles still carry enough connotations of militant blackness to annoy the bourgeoisie.

One key thing differentiates OWS’s drummers from the demonstrations of yore, however: in the 60s and early 70s, there was a notion that drum circles were for drummers. Santana’s band, though young, was made up of world class musicians from the San Francisco scene. But to a certain type of viewer – young, white and male—the drum circle must have seemed so doable. Compared to the singular virtuosity of Jimi Hendrix or sheer talent of Pete Townshend, Santana’s music was the sonic equivalent of socialism. No wonder the drum circle scene has had more of a half-life in the hearts and minds of would-be Woodstockians than just about any other: it is a visceral depiction of music as communal, ecstatic, and accessible. Today, thanks to the far-reaching waves of the movie Woodstock: 3 Days of Peace & Music (1970), the percussive noise such a circle makes creates a particular sonic backdrop that clearly—and nostalgically—says hippiesomething.

And yet, politically speaking, nostalgia is, as theorists like Antonio Gramsci, Guy Debord, Jacques Attali and Theodor Adorno have frequently reminded us, invariably associated with Fascism. From Mussolini to Hitler to Reagan to Glenn Beck, it’s a tactic that has been explicitly invoked to thwart social progress. The nostalgia conundrum seems to have escaped both mainstream news media—which uses the drum circle to signify to viewers that OWS is a radical leftist plot—as well as the drummers themselves. For the drummers are hippies, and hippies young and old really believe in drum circles. Hippies take part in them, hippies enjoy them. It’s fair to say, however, that few others do, just as no one ever really enjoyed the 45- minute drum solos on live records by Cream, Led Zeppelin, and Iron Butterfly. (I’m thinking about Ginger Baker’s “Toad,” John Bonham’s “Moby Dick,” and “In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida,” respectively. Also about the time I went to the bathroom and bought popcorn at the LA Forum during a drum solo by some band I know forget, and still had to sit through ten more minutes.) .

However, that fact does not seem to bother those involved in drum circles, and herein lies the great problem with the whole equation drum + hippie = activism. To any members of the mainstream media who hears and records them, a drum circle instantly conjures up a chaotic, possibly even violent, scene: Chicago ‘68, Seattle 2000, Oakland 2011. But the truth is that, outside Fox News, the noun “hippie” no longer means “liberal,” or possibly even politically engaged. The curious thing about drum circles, then, is that while they sound progressive, they can actually mean conservative. A 2006 piece from NPR, for example, describes how drum circles have been adapted as teambuilding exercises for corporations like Apple, Microsoft, and McDonald’s.

The OWS situation illustrates such conservatism in different ways. In another recent article in New York Magazine, a 19 year old drummer from New Jersey is quoted as saying, “Drumming is the heartbeat of this movement. Look around: This is dead, you need a pulse to keep something alive.” This is said in the face of opposition from the movement’s own management, who fear a shutdown due to severe problems with neighborhood groups and restrictions on the General Assembly’s call-and-response “mic checks” that have been so galvanizing. His words are instructive as well as ominous, illustrating that young hippies like him believe that the sound of drums is a suitable replacement for protest or action itself.

The idea that sound alone can energize a movement is not just wrong, it also showcases a willful misunderstanding within the ranks of OWS. In Oakland last week, a small band of anarchists threw bottles at the police, whose wrath rained down in the form of tear gas canisters and a fusillade of dowels: one protester, an Iraq veteran, has been seriously injured.

The incident highlights a kind of cognitive dissonance that is hindering the ability of OWS to achieve political progress. The drumming problems at Zuccotti Park highlight the way that history can repeat itself as farce, as the distance between nostalgia and action — and between sound and meaning — disturbs the peace in more ways than one. Just as drummers in Sproul Plaza refuse to acknowledge that UC Berkeley is now mainly host to computer science and business majors, and drummers in Golden Gate Park refuse to deal with a Haight Ashbury that is gentrifying in front of their eyes, so too do the drummers at OWS refuse to acknowledge that their sound is no longer the sound of social activism. Indeed, the sound of a drum circle is reminiscent of the ring of a telephone, the scratch of a needle dropped on a record, or the clip clop of horse hoofs on hay-covered streets. No wonder it sounds out of place at OWS.

—

Gina Arnold recently received her Ph.D. in the program of Modern Thought & Literature at Stanford University, where she is currently a post doctoral scholar. Prior to beginning graduate work, she was a rock critic. Her dissertation, which draws on historical archives, literature, and films about counter cultural rock festivals of the 1960s and 1970 as well as on her own experience covering the less counter cultural rock festivals of the 1990s, is called Rock Crowds & Power. It is about rock crowds and power.

‘Corn-ing’ the Suburbs on Halloween, a Sonic Trick and Treat

It was a crisp Saturday night in late-October. I was probably seven or eight. My brother and I were sitting on the couch watching “It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown” for the zillionth time.

And then we heard it.

To our stunned ears, it seemed as though my parents’ bay window, situated directly behind us, had shattered to pieces. But, mysteriously, it was still there, in tact.

Our tiny nervous systems were not prepared for this sonic assault, especially because it didn’t make sense. We stared in disbelief at the window for a minute, waiting for it to spill its shards. When we got enough courage to get up and peer out the front door, we saw the lanky silhouettes of teenagers running away into the dark of the trees. Piles of dried out corn kernels were scattered all over the porch like empty shells. We had been corned.

“Corn-ing,” a longstanding Halloween tradition in the suburbs of western Pennsylvania, is a popular prank in which kids sneak up to houses after dark and throw pre-hardened corn kernels at their windows, producing a truly startling sound effect. Corn-ing’s treat lies in the sonic trick—corn is able to convincingly sound like something else entirely. Thinking back on my experiences as both a victim of and participant in corn-ing, it occurs to me that this prank is sonic through and through—from listening for farmers in the corn fields before snatching husks from their crops, to locating one’s corn-ing partners in pitch black environments by the sound of the kernels bouncing rhythmically in their backpacks.

When early October rolled around each year, it was like an alarm went off in the heads of the kids that lived in my neighborhood. October meant it was time to procure ears of corn from the farms located on the outskirts of our Wonder-Years-ish suburb. In the days before we had our drivers’ licenses, this was an arduous task. We’d have to ride our bikes on the hilly back roads in mid-day (night time was too scary after we’d seen Children of the Corn), ditch them in the woods near the fields, and listen carefully for any signs of life in the corn—farmers, animals, blood-thirsty fundamentalist Christian children named Malachi, etc.

We couldn’t rely on our sight in these instances because the corn was so tall. We had to stop filling our backpacks every so often and listen for sounds of danger—for the rustles and crunches of stalks.

After our backpacks were filled to the brim, the preparation process began. The corn would sit for weeks in our garage, getting harder and harder. Once it became pebble-like in consistency, we’d shuck it back into our backpacks, listening to the pinging sound as it accumulated. On Friday afternoons, anxiously waiting for the sun to go down, we’d talk strategy. We decided that corning old people was out of the question. Even in our pseudo-delinquent state, we realized that sound had consequences—that spooking someone could give them a heart attack. So we mostly stuck to mean neighbors like old man Haybee, who was notorious for the unsightly cursive green “H” that was bolted to his chimney like a garish fast food sign. He never gave out candy to trick or treaters, so he was basically asking for it. Once a plan of attack was developed, it was time to suit up in all-black clothing and put on our packs. As soon as the streetlights came on, we were off.

My memories of these adolescent adventures are predominately sonic—the crunch of the fallen leaves, pounding hearts and nervous breathing, barely muffled laughter, and of course the sound of corn making contact with glass. Indeed, the success of the prank was measured in sound. The louder the sound the corn produced, the louder the aftermath tended to be. It was a true victory if dogs barked, or if people came out of their houses to yell. “You damn kids better run!” they would scream, sometimes only half seriously. And we did. We ran for our lives, despite the oppressive weight of the corn on our backs.

Click for the sound of sorn-ing: corn-ing

I wanted to capture the sounds of a real corn-ing experience to include here, but I quickly realized what an incredibly stupid idea that would be (what you heard, by the way, was the sound of me and my neighbor corning our own apartment building). As an almost 30-year-old Pittsburgher living in a fairly rough neighborhood, sneaking up to people’s houses at night in order to produce startling noises would most likely result in an encounter with police or violence of some kind. In the suburban environment of my adolescence, the sound of corn-ing was associated with a silly prank. Neighbors came to expect (and even get a kick out of) this Halloween tradition. In an urban environment in which the corn-ers are no longer in their teens, however, the sound of corn-ing would most almost certainly be interpreted as an aggressive or threatening act.

This just goes to show that different configurations of sound, spaces, and bodies (particularly raced and classed bodies) can result in vastly different understandings about what it means to share sound in a community. In Pittsburgh, I find myself constantly bombarded with the sounds of emergency and panic—police and ambulance sirens, firetrucks, helicopters. In my community’s soundscape, loud, startling noises are definitely not associated with fun and folly. Rather, they are a constant reminder of the looming danger that apparently surrounds me, as well as the incessant surveillance and policing of the city. This does not leave much room for sonic play.

This is not to say that there was no danger in corn-ing the burbs. For instance, this recent tragedy, in which a corn-er accidentally was hit by a car, happened in a suburb not far from the one where I grew up. Back when I was pitching corn, my best friend Courtney was once tackled by a man who thought she was slashing the tires of his truck (she was really just hiding behind a tire with a fistful of corn). And my brother Matt and I often found ourselves taking cover in the neighbors’ shrubbery waiting for the town patrolman to finish his watch. But I’d imagine that these war stories would not even come close to the dangers of corn-ing in the city. It is clear that the effectiveness of corn-ing as a prank is contingent upon the specific time, season, location, and culture in which its sounds occur.

Perhaps the real trick of sound, then, is that the context of its sounding can completely transform its effects and affects. But if you can get the sounds in sync with the right context, well, then you’ve got yourself a real treat.

—–

Steph Ceraso is a 4th year Ph.D. student in English (Cultural/ Critical Studies) at the University of Pittsburgh specializing in rhetoric and composition. Her primary research areas include sound and listening, digital media, and affect. Ceraso is currently writing a dissertation that attempts to revise and expand conventional notions of listening, which tend to emphasize the ears while ignoring the rest of the body. She is most interested in understanding how more fully embodied modes of listening might deepen our knowledge of multimodal engagement and production. Ceraso is also a 2011-12 HASTAC [Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Advanced Collaboratory] Scholar and a DM@P [Digital Media at Pitt] Fellow. She regularly blogs for HASTAC.

Recent Comments