“This AI will heat up any club”: Reggaetón and the Rise of the Cyborg Genre

This series listens to the political, gendered, queer(ed), racial engagements and class entanglements involved in proclaiming out loud: La-TIN-x. ChI-ca-NA. La-TI-ne. ChI-ca-n-@. Xi-can-x. Funded by an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation as part of the Crossing Latinidades Humanities Research Initiative, the Latinx Sound Cultures Studies Working Group critically considers the role of sound and listening in our formation as political subjects. Through both a comparative and cross-regional lens, we invite Latinx Sound Scholars to join us as we dialogue about our place within the larger fields of Chicanx/Latinx Studies and Sound Studies. We are delighted to publish our initial musings with Sounding Out!, a forum that has long prioritized sound from a queered, racial, working-class and “always-from-below” epistemological standpoint. —Ed. Dolores Inés Casillas

—

Busco la colaboración universal donde todos los Benitos puedan llegar a ser Bad Bunny. –FlowGPT, TikTok

In November of 2023, the reggaetón song “DEMO #5: NostalgIA” went viral on various digital platforms, particularly TikTok. The track, posted by user FlowGPT, makes use of artificial intelligence (Inteligencia Artificial) to imitate the voices of Justin Bieber, Bad Bunny, and Daddy Yankee. The song begins with a melody reminiscent of Justin Bieber’s 2015 pop hit “Sorry.” Soon, reggaetón’s characteristic boom-ch-boom-chick drumbeat drops, and the voices of the three artists come together to form a carefully crafted, unprecedented crossover.

Bad Bunny’s catchy verse “sal que te paso a buscar” quickly inundated TikTok feeds as users began to post videos of themselves dancing or lip-syncing to the song. The song was not only very good but it also successfully replicated these artists– their voices, their style, their vibe. Soon, the song exited the bounds of the digital and began to be played in clubs across Latin America, marking a thought-provoking novelty in the usual repertoire of reggaetón hits. In line with the current anxieties around generative AI, the song quickly generated public controversy. Only a few weeks after its release, ‘nostalgIA’ was taken down from most digital platforms.

The mind behind FlowGPT is Chilean producer Maury Senpai, who in a series of TikTok responses explained his mission of creative democratization in a genre that has been historically exclusive of certain creators. In one video, FlowGPT encourages listeners to contemplate the potential of this “algorithm” to allow songs by lesser-known artists and producers to reach the ears of many listeners, by replicating the voices of well-known singers. Maury Senpai’s production process involved lyric writing, extensive study of the singers’ vocals, and the Kits.ai tool.

Therefore, contrary to FlowGPT’s robotic brand, ‘nostalgIA’ was the product of careful collaboration between human and machine– or, what Ross Cole calls “cyborg creativity.” This hybridization enmeshes the artist and the listener, allowing diverse creators their creative desires. Cyborg creativity, of course, is not an inherent result of GenAI’s advent. Instead, I argue that reggaetón has long been embedded in a tradition of musical imitation and a deep reliance on technological tools, which in turn challenges popular concerns about machine-human artistic collaboration.

Many creators worry that GenAI will co-opt a practice that for a long time has been regarded as strictly human. GenAI’s reliance on pre-existing data threatens to hide the labor of artists who contributed to the model’s output. We may also add the inherent biases present in training data. Pasquinelli and Joler propose that the question “Can AI be creative?” be reformulated as “Is machine learning able to create works that are not imitations of the past?” Machine learning models detect patterns and styles in training data and then generate “random improvisation” within this data. Therefore, GenAI tools are not autonomous creative actors but often operate with generous human intervention that trains, monitors, and disseminates the products of these models.

The inability to define GenAI tools as inherently creative on their own does not mean they can’t be valuable for artists seeking to experiment in their work. Hearkening back to Donna Haraway’s concept of the cyborg, Ross Cole argues that

Such [AI] music is in fact a species of hybrid creativity predicated on the enmeshing of people and computers (…) We might, then, begin to see AI not as a threat to subjective expression, but another facet of music’s inherent sociality.

Many authors agree that unoriginal content—works that are essentially reshufflings of existing material—cannot be considered legitimate art. However, an examination of the history of the reggaetón genre invites us to question this idea. In “From Música Negra to Reggaetón Latino,” Wayne Marshall explains how the genre emerged from simultaneous and mutually-reinforcing processes in Panamá, Puerto Rico, and New York, where artists brought together elements of dancehall, reggae, and American hip hop. Towards the turn of the millennium, the genre’s incorporation of diverse musical elements and the availability of digital tools for production favored its commercialization across Latin America and the United States.

The imitation of previous artists has been embedded in the fabric of reggaetón from a very early stage. Some of the earliest examples of reggaetón were in fact Spanish lyrics placed over Jamaican dancehall riddims— instrumental tracks with characteristic melodies. When Spanish-speaking artists began to draw from dancehall, they used these same riddims in their songs, and continue to do so today. A notable example of this pattern is the Bam Bam riddim, which is famously used in the song “Murder She Wrote” by Chaka Demus & Pliers (1992).

This riddim made its way into several reggaetón hits, such as “El Taxi” by Osmani García, Pitbull, and Sensato (2015).

We may also observe reggaetón’s tradition of imitation in frequent references to “old school” artists by the “new school,” through beat sampling, remixes, and features. We see this in Karol G’s recent hit “GATÚBELA,” where she collaborates with Maldy, former member of the iconic Plan B duo.

Reggaetón’s deeply rooted tradition of “tribute-paying” also ties into its differentiation from other genres. As the genre grew in commercial value, perhaps to avoid copyright issues, producers cut down on their direct references to dancehall and instead favored synthesized backings. Marshall quotes DJ El Niño in saying that around the mid-90s, people began to use the term reggaetón to refer to “original beats” that did not solely rely on riddims but also employed synthesizer and sequencer software. In particular, the program Fruity Loops, initially launched in 1997, with “preset” sounds and effects provided producers with a wider set of possibilities for sonic innovation in the genre.

The influence of technology on music does not stop at its production but also seeps into its socialization. Today, listeners increasingly engage with music through AI-generated content. Ironically, following the release of Bad Bunny’s latest album, listeners expressed their discontent through AI-generated memes of his voice. One of the most viral ones consisted of Bad Bunny’s voice singing “en el McDonald’s no venden donas.”

The clip, originally sung by user Don Pollo, was modified using AI to sound like Bad Bunny, and then combined with reggaetón beats and the Bam Bam riddim. Many users referred to this sound as a representation of the light-heartedness they saw lacking in the artist’s new album. While Un Verano Sin Ti (2022) stood out as an upbeat summer album that addressed social issues such as U.S. imperialism and machismo, Nadie Sabe lo que va a Pasar Mañana (2023) consisted mostly of tiraderas or disses against other artists and left some listeners disappointed. In a 2018 post for SO!, Michael S. O’Brien speaks of this sonic meme phenomenon, where a sound and its repetition come to encapsulate collective discontent.

Another notorious case of AI-generated covers targets recent phenomenon Young Miko. As one of the first openly queer artists to break into the urban Latin mainstream, Young Miko filled a long-standing gap in the genre—the need for lyrics sung by a woman to another woman. Her distinctive voice has also been used in viral AI covers of songs such as “La Jeepeta,” and “LALA,” originally sung by male artists. To map Young Miko’s voice over reggaetón songs that advance hypermasculinity– through either a love for Jeeps or not-so-subtle oral sex– represents a creative reclamation of desire where the agent is no longer a man, but a woman. Jay Jolles writes of TikTok’s modifications to music production, namely the prioritization of viral success. The case of AI-generated reggaetón covers demonstrates how catchy reinterpretations of an artist’s work can offer listeners a chance to influence the music they enjoy, allowing them to shape it to their own tastes.

Examining the history of musical imitation and digital innovation in reggaetón expands the bounds of artistry as defined by GenAI theorists. In the conventions of the TikTok platform, listeners have found a way to participate in the artistry of imitation that has long defined the genre. The case of FlowGPT, along with the overwhelmingly positive reception of “nostalgIA,” point towards a future where the boundaries between the listener and the artist are blurred, and where technology and digital spaces are the platforms that allow for an enhanced cyborg creativity to take place.

—

Featured Image: Screenshot from ““en el McDonald’s no venden donas.” Taken by SO!

—

Laurisa Sastoque is a Colombian scholar of digital humanities, history, and storytelling. She works as a Digital Preservation Training Officer at the University of Southampton, where she collaborates with the Digital Humanities Team to promote best practices in digital preservation across Galleries/Gardens, Libraries, Archives, and Museums (GLAM), and other sectors. She completed an MPhil in Digital Humanities from the University of Cambridge as a Gates Cambridge scholar. She holds a B.A. in History, Creative Writing, and Data Science (Minor) from Northwestern University.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Boom! Boom! Boom!: Banda, Dissident Vibrations, and Sonic Gentrification in Mazatlán—Kristie Valdez-Guillen

Listening to MAGA Politics within US/Mexico’s Lucha Libre –Esther Díaz Martín and Rebeca Rivas

Ronca Realness: Voices that Sound the Sucia Body—Cloe Gentile Reyes

Echoes in Transit: Loudly Waiting at the Paso del Norte Border Region—José Manuel Flores & Dolores Inés Casillas

Experiments in Agent-based Sonic Composition—Andreas Pape

Echo and the Chorus of Female Machines

Editor’s Note: February may be over, but our forum is still on! Today I bring you installment #5 of Sounding Out!‘s blog forum on gender and voice. Last week Art Blake talked about how his experience shifting his voice from feminine to masculine as a transgender man intersects with his work on John Cage. Before that, Regina Bradley put the soundtrack of Scandal in conversation with race and gender. The week before I talked about what it meant to have people call me, a woman of color, “loud.” That post was preceded by Christine Ehrick‘s selections from her forthcoming book, on the gendered soundscape. We have one more left! Robin James will round out our forum with an analysis of how ideas of what women should sound like have roots in Greek philosophy.

Editor’s Note: February may be over, but our forum is still on! Today I bring you installment #5 of Sounding Out!‘s blog forum on gender and voice. Last week Art Blake talked about how his experience shifting his voice from feminine to masculine as a transgender man intersects with his work on John Cage. Before that, Regina Bradley put the soundtrack of Scandal in conversation with race and gender. The week before I talked about what it meant to have people call me, a woman of color, “loud.” That post was preceded by Christine Ehrick‘s selections from her forthcoming book, on the gendered soundscape. We have one more left! Robin James will round out our forum with an analysis of how ideas of what women should sound like have roots in Greek philosophy.

This week Canadian artist and writer AO Roberts takes us into the arena of speech synthesis and makes us wonder about what it means that the voices are so often female. So, lean in, close your eyes, and don’t be afraid of the robots’ voices. –Liana M. Silva, Managing Editor

—

I used Apple’s SIRI for the first time on an iPhone 4S. After hundreds of miles in a van full of people on a cross-country tour, all of the music had been played and the comedy mp3s entirely depleted. So, like so many first time SIRI users, we killed time by asking questions that went from the obscure to the absurd. Passive, awaiting command, prone to glitches: there was something both comedic and insidious about SIRI as female-gendered program, something that seemed to bind up the technology with stereotypical ideas of femininity.

Speech synthesis is the artificial simulation of the human voice through hardware or software, and SIRI is but one incarnation of the historical chorus of machines speaking what we code to be female. Starting from the early 20th century Voder, to the Cold-War era Silvia and Audrey, up to Amazon’s newly released Echo, researchers have by and large developed these applications as female personae. Each program articulates an individual timbre and character, soothing soft spoken or matter of fact; this is your mother, sister, or lover, here to affirm your interests while reminding you about that missed birthday. She is easy to call up in memory, tones rounded at the edges, like Scarlett Johansson’s smoky conviviality as Samantha in Spike Jonze’s Her, a bodiless purr. Simulated speech articulates a series of assumptions about what neutral articulation is, what a female voice is, and whose voice technology can ventriloquize.

The ways computers hear and speak the human voice are as complex as they are rapidly expanding. But in robotics gender is charted down to actual wavelength, actively policed around 100-150 HZ (male) and 200-250 HZ (female). Now prevalent in entertainment, navigation, law enforcement, surveillance, security, and communications, speech synthesis and recognition hold up an acoustic mirror to the dominant cultures from which they materialize. While they might provide useful tools for everything from time management to self-improvement, they also reinforce cisheteronormative definitions of personhood. Like the binary code that now gives it form, the development of speech recognition separated the entire spectrum of vocal expression into rigid biologically based categories. Ideas of a real voice vs. fake voice, in all their resonances with passing or failing one’s gender performance, have through this process been designed into the technology itself.

A SERIES OF MISERABLE GRUNTS

“Kempelen Speakingmachine” by Fabian Brackhane (Quintatoen), Saarbrücken – Own work. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons –

The first voice to be synthesized was a reed and bellows box invented by Wolfgang Von Kempelen in 1791 and shown off in the courts of the Hapsburg Empire. Von Kempelen had gained renown for his chess-playing Turk, a racist cartoon of an automaton that made waves amongst the nobles until it was revealed that underneath the tabletop was a small man secretly moving the chess player’s limbs. Von Kempelen’s second work, the speaking machine, wowed its audiences thoroughly. The player wheedled and squeezed the contraption, pushing air through its reed larynx to replicate simple words like mama and papa.

Synthesizing the voice has always required some level of making strange, of phonemic abstraction. Bell Laboratories originally developed The Voder, the earliest incarnation of the vocoder, as a cryptographic device for WWII military communications. The machine split the human voice into a spectral representation, fragmenting the source into number of different frequencies that were then recombined into synthetic speech. Noise and unintelligibility shielded the Allies’ phone calls from Nazi interception. The Vocoder’s developer, Ralph Miller, bemoaned the atrocities the machine performed on language, reducing it to a “series of miserable grunts.”

From website Binary Heap-

In his history of the The Vocoder, How to Wreck a Nice Beach, Dave Tompkins tells how the apparatus originally took up an entire wall and was played solely by female phone operators, but the pitch of the female voice was said to be too high to be heard by the nascent technology. In fact, when it debuted at the 1939 World’s Fair, only men were chosen to experience the roboticization of their voice. The Voder was, in fact, originally created to only hear pitches in the range of 100-150 HZ, a designed exclusion from the start. So when the Signal Corps of the Army convinced President Eisenhower to call his wife via Voder from North Africa, Miller and the developers panicked for fear she wouldn’t be heard. Entering the Pentagon late at night, Mamie Eisenhower spoke into the telephone and a fragmented version of her words travelled across the Atlantic. Resurfacing in angular vocoded form, her voice urged her husband to come home, and he had no problem hearing her. Instead of giving the developers pause to question their own definitions of gender, this interaction is told as a derisive footnote of in the history of the sound and technology: the punchline being that the first lady’s voice was heard because it was as low as a man’s.

WAKE WORDS

In fall 2014 Amazon launched Echo, their new personal assistant device. Echo is a 12-inch long plain black cone that stands upright on a tabletop, similar in appearance to a telephoto camera lens. Equipped with far field mics, Echo has a female voice, connected to the cloud and always on standby. Users engage Echo with their own chosen ‘wake’ word. The linguistic similarity to a BDSM safe word could have been lost on developers. Although here inverted, the word is used to engage rather than halt action, awakening an instrument that lays dormant awaiting command.

Amazon’s much-parodied promotional video for Echo is narrated by the innocent voice of the youngest daughter in a happy, straight, white, middle-class family. While the son pitches Oedipal jabs at the father for his dubious role as patriarchal translator of technology, each member of the family soon discovers the ways Echo is useful to them. They name it Alexa and move from questions like: “Alexa how many teaspoons in a tablespoon” and “How tall is Mt. Everest?” to commands for dance mixes and cute jokes. Echo enacts a hybrid role as mother, surrogate companion, and nanny of sorts not through any real aspects of labor but through the intangible contribution of information. As a female-voiced oracle in the early pantheon of the Internet of Things, Echo’s use value is squarely placed in the realm of cisheteronormative domestic knowledge production. Gone are the tongue-in-cheek existential questions proffered to SIRI upon its release. The future with Echo is clean, wholesome, and absolutely SFW. But what does it mean for Echo to be accepted into the home, as a female gendered speaking subject?

Concerns over privacy and surveillance quickly followed Echo’s release, alarms mostly sounding over its “always on” function. Amazon banks on the safety and intimacy we culturally associate with the female voice to ease the transition of robots and AI into the home. If the promotional video painted an accurate picture of Echo’s usage, it would appear that Amazon had successfully launched Echo as a bodiless voice over the uncanny valley, the chasm below littered with broken phalanxes of female machines. Masahiro Mori coined the now familiar term uncanny valley in 1970 to describe the dip in empathic response to humanoid robots as they approach realism.

If we listen to the litany of reactions to robot voices through the filters of gender and sexuality it reveals the stark inclines of what we might think of as a queer uncanny valley. Paulina Palmer wrote in The Queer Uncanny about reoccurring tropes in queer film and literature, expanding upon what Freud saw as a prototypical aspect of the uncanny: the doubling and interchanging of the self. In the queer uncanny we see another kind of rift: that between signifier and signified embodied by trans people, the tearing apart of gender from its biological basis. The non-linear algebra of difference posed by queer and trans bodies is akin to the blurring of divisions between human and machine represented by the cyborg. This is the coupling of transphobic and automatonophobic anxieties, defined always in relation to the responses and preoccupations of a white, able bodied, cisgendered male norm. This is the queer uncanny valley. For the synthesized voice to function here, it must ease the chasm, like Echo: sutured by a voice coded as neutral, but premised upon the imagined body of a white, heterosexual, educated middle class woman.

22% Female

My own voice spans a range that would have dismayed someone like Ralph Miller. I sang tenor in Junior High choir until I was found out for straying, and then warned to stay properly in the realms of alto, but preferably soprano range. Around the same time I saw a late night feature of Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady, struggling to lose her crass proletariat inflection. So I, a working class gender ambivalent kid, walked around with books on my head muttering The Rain In Spain Falls Mainly on the Plain for weeks after. I’m generally loud, opinionated and people remember me for my laugh. I have sung in doom metal and grindcore punk bands, using both screeching highs and the growling “cookie monster” vocal technique mostly employed by cismales.

My own voice spans a range that would have dismayed someone like Ralph Miller. I sang tenor in Junior High choir until I was found out for straying, and then warned to stay properly in the realms of alto, but preferably soprano range. Around the same time I saw a late night feature of Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady, struggling to lose her crass proletariat inflection. So I, a working class gender ambivalent kid, walked around with books on my head muttering The Rain In Spain Falls Mainly on the Plain for weeks after. I’m generally loud, opinionated and people remember me for my laugh. I have sung in doom metal and grindcore punk bands, using both screeching highs and the growling “cookie monster” vocal technique mostly employed by cismales.

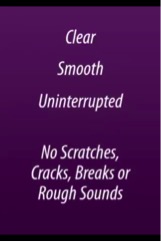

Given my own history of toying with and estrangement from what my voice is supposed to sound like, I was interested to try out a new app on the market, the Exceptional Voice App (EVA ), touted as “The World’s First and Only Transgender Voice Training App.” Functioning as a speech recognition program, EVA analyzes the pitch, respiration, and character of your voice with the stated goal of providing training to sound more like one’s authentic self. Behind EVA is Kathe Perez, a speech pathologist and businesswoman, the developer and provider of code to the circuit. And behind the code is the promise of giving proper form to rough sounds, pitch-perfect prosody, safety, acceptance, and wholeness. Informational and training videos are integrated with tonal mimicry for phrases like hee, haa, and ooh. User progress is rated and logged with options to share goals reached on Twitter and Facebook. Customers can buy EVA for Gals or EVA for Guys. I purchased the app online for my iPhone for $5.97.

Given my own history of toying with and estrangement from what my voice is supposed to sound like, I was interested to try out a new app on the market, the Exceptional Voice App (EVA ), touted as “The World’s First and Only Transgender Voice Training App.” Functioning as a speech recognition program, EVA analyzes the pitch, respiration, and character of your voice with the stated goal of providing training to sound more like one’s authentic self. Behind EVA is Kathe Perez, a speech pathologist and businesswoman, the developer and provider of code to the circuit. And behind the code is the promise of giving proper form to rough sounds, pitch-perfect prosody, safety, acceptance, and wholeness. Informational and training videos are integrated with tonal mimicry for phrases like hee, haa, and ooh. User progress is rated and logged with options to share goals reached on Twitter and Facebook. Customers can buy EVA for Gals or EVA for Guys. I purchased the app online for my iPhone for $5.97.

My initial EVA training scores informed me I was 22% female; a recurring number I receive in interfaces with identity recognition software. Facial recognition programs consistently rate my face at 22% female. If I smile I tend to get a higher female response than my neutral face, coded and read as male. Technology is caught up in these translations of gender: we socialize women to smile more than men, then write code for machines to recognize a woman in a face that smiles.

As for EVA’s usage, it seems to be a helpful pedagogical tool with more people sharing their positive results and reviews on trans forums every day. With violence against trans people persisting—even increasing—at alarming rates, experienced worst by trans women of color, the way one’s voice is heard and perceived is a real issue of safety. Programs like EVA can be employed to increase ease of mobility throughout the world. However, EVA is also out of reach to many, a classed capitalist venture that tautologically defines and creates users with supply. The context for EVA is the systems of legal, medical, and scientific categories inherited from Foucault’s era of discipline; the predetermined hallucination of normal sexuality, the invention of biological criteria to define the sexes and the pathologization of those outside each box, controlled by systems of biopower.

Despite all these tools we’ll never really know how we sound. It is true that the resonant chamber of our own skull provides us with a different acoustic image of our own voice. We hate to hear our voice recorded because suddenly we catch a sonic glimpse of what other people hear: sharper more angular tones, higher pitch, less warmth. Speech recognition and synthesis work upon the same logic, the shifting away from interiority; a just off the mark approximation. So the question remains what would a gender variant voice synthesis and recognition sound like? How much is reliant upon the technology and how much depends upon individual listeners, their culture, and what they project upon the voice? As markets grow, so too have more internationally accented English dialects been added to computer programs with voice synthesis. Thai, Indian, Arabic and Eastern European English were added to Mac OSX Lion in 2011. Can we hope to soon offer our voices to the industry not as a set of data to be mined into caricatures, but as a way to assist in the opening up in gender definitions? We would be better served to resist the urge to chime in and listen to the field in the same way we suddenly hear our recorded voice played back, with a focus on the sour notes of cold translation.

—

Featured image: “Golden People love Gold Jewelry Robots” by Flickr user epSos.de, CC BY 2.0

—

AO Roberts is a Canadian intermedia artist and writer based in Oakland whose work explores gender, technology and embodiment through sound, installation and print. A founding member of Winnipeg’s NGTVSPC feminist artist collective, they have shown their work at galleries and festivals internationally. They have also destroyed their vocal chords, played bass and made terrible sounds in a long line of noise projects and grindcore bands, including VOR, Hoover Death, Kursk and Wolbachia. They hold a BFA from the University of Manitoba and a MFA in Sculpture from California College of the Arts.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Hearing Queerly: NBC’s “The Voice”—Karen Tongson

On Sound and Pleasure: Meditations on the Human Voice—Yvon Bonefant

I Been On: BaddieBey and Beyoncé’s Sonic Masculinity—Regina Bradley

Recent Comments