The Braids, The Bars, and the Blackness: Ruminations on Hip Hop’s World War III – Drake versus Kendrick (Part One)

A Conversation by Todd Craig and LeBrandon Smith

By now, it’s safe to say very few people have not caught wind of the biggest Hip-Hop battle of the 21st century: the clash between Kendrick Lamar and Drake. Whether you’ve seen the videos, the memes or even smacked a bunch of owls around playing the video game, this battle grew beyond Hip Hop, with various facets of global popular culture tapped in, counting down minutes for responses and getting whiplash with the speed of song drops. There are multiple ways to approach this event. We’ve seen inciteful arguments about how these two young Black males at the pinnacle of success are tearing one another down. We also acknowledge Hip Hop’s long legacy of battling; the culture has always been a “competitive sport” that includes “lyrical sparring.”

This three-part article for Sounding Out!’s Hip Hop History Month edition stems from a longer conversation with two co-authors and friends, Hip Hop listeners and aficionados, trying to make sense of all the songs and various aspects of the visuals. This intergenerational conversation involving two different sets of Hip Hop listening ears, both heavily steeped in Hip Hop’s sonic culture, is important. Our goal here is to think through this battle by highlighting quotes from songs that resonated with us as we chronicled this moment. We hope this article serves as a responsible sonic assessment of this monumental Hip Hop episode.

First things first: what’s so intergenerational about our viewpoints? This information provides some perspective on how this most recent battle resonated with two avid Hip Hop listeners and cultural participants.

LeBrandon is a 33 year old Black male raised in Brooklyn and Queens, New York. He is an innovative curator and social impact leader. When asked about the first Hip Hop beef that impacted him, LeBrandon said:

The first Hip-Hop battle I remember is Jay x Nas and mainly because Jay was my favorite rapper at the time. I was young but mature enough to feel the burn of “Ether.” It’s embarrassing to say now, but truthfully I was hurt—as if “Ether” had been pointed at me. “Ether” is a masterclass in Hip Hop disrespect but the stanza that I remember feeling terrible about was “I’ll still whip your ass/ you 36 in a karate class?/ you Tae-bo hoe/ tryna work it out/ you tryna get brolic/ Ask me if I’m tryna kick knowledge/ Nah I’m tryna kick the shit you need to learn though/ that ether, that shit that make your soul burn slow.” MAN. I remember thinking, is Jay old?! Is 36 old?! Is my favorite rapper old?! Why did Nas say that about him? I should reiterate I am older now and don’t think 36 is old, related or unrelated to Hip Hop. Nas’s gloves off approach shocked me and genuinely concerned me. But I’m thankful for the exposure “Ether” gave me to the understanding that anything goes in a Hip-Hop battle.

Todd is a Black male who grew up in Ravenswood and Queensbridge Houses in Long Island City, New York. Todd is about 15 years older than LeBrandon, and is an associate professor of African American Studies and English. Todd stated:

The first battle that engaged my Hip Hop senses was the BDP vs. Juice Crew battle –specifically “The Bridge” and “The Bridge is Over.” The stakes were high, the messages were clear-cut, and the battle lines were drawn. I lived in Ravenswood but I had family and friends in QB. And “The Bridge” was like a borough anthem. Even though MC Shan was repping the Bridge, that song motivated and galvanized our whole area in Long Island City. This was the first time in Hip Hop that I recall needing to choose a side. And because I had seen Shan and Marley and Shante in real life in QB, the choice was a no-brainer. That battle led me to start recording Mr. Magic and Marley Marl’s show on 107.5 WBLS, before even checking out what Chuck Chillout or Red Alert was doing. As I got older, it would sting when I heard “The Bridge is Over” at a club or a party. And when I would DJ, I’d always play “The Bridge is Over” first, and follow it up with either “The Bridge” or another QB anthem, like a “Shook Ones Pt. 2” or something.

We both enter this conversation agreeing this battle has been brewing for about ten years, however it really came to a head in the Drake and J. Cole song, “First Person Shooter.” Evident in the song is J. Cole’s consistent references to the “Big Three” (meaning Kendrick Lamar, Drake and J. Cole atop Hip-Hop’s food chain), while Drake was very much focused on himself and Cole. It is rumored that Kendrick was asked to be on the song; his absence without some lyrical revision by Cole and Drake, seems to have led to Kendrick feeling snubbed or slighted in some way. This song gets Hip Hop listeners to Kendrick’s verse on the Future and Metro Boomin’ song “Like That” where Kendrick sets Hip Hop ablaze with the simple response: “Muthafuck the Big Three, nigguh, it’s just Big Me” – a moment where he “takes flight” and avoids the “sneak dissing” that he asserts Drake has consistently done.

We both agreed that Drake’s initial full-length entry into this battle, “Push Ups,” was the typical diss record we’d expect from him. Whether in his battle with Meek Mill or Pusha T, Drake’s entry follows the typical guidelines for diss records: it comes with a series of jabs at an opponent, which starts the war of words. The goal in a battle is always to disrespect your opponent to the fullest extent, so we find Drake aiming to do just that. We both noticed those jabs, most memorably is “how you big steppin’ with some size 7 men’s on.” We also noticed Drake’s misstep by citing the wrong label for Kendrick when he says “you’re in the scope right now” – alluding to Kendrick Lamar being signed to Interscope – even though neither Top Dog Entertainment (TDE) nor PGLang are signed to Interscope Records. Drake’s lack of focus on just Kendrick would prove a mistake: he disses Metro Boomin, The Weeknd, Rick Ross, and basketball player Ja Morant in “Push Ups.”

While we agree that in a rap battle, the goal is to disrespect your opponent at the highest level, we had differing perspectives on Drake’s second diss track “Taylor Made Freestyle.” LeBrandon felt this song landed because it took a “no fucks” approach to the battle. Regardless of how one may feel about Drake’s method of disrespect (by using AI), the message was loud and inescapable. LeBrandon highlighted the moment when AI Tupac says “Kendrick we need ya!”; outside of how hilarious this line is, Drake dissing Kendrick by using Tupac’s voice – a person with a legacy that Kendrick holds in the highest esteem – further established that this would be no friendly sparring match. Not only did Drake disrespect a Hip Hop legend with this line and its delivery, but an entire coast. The track invokes the spirit of a deceased rapper, specifically one whose murder was so closely connected to Hip Hop and authentic street beef. This moment was a step too far for Todd, who lived through the moment when both 2Pac and Biggie were murdered over fabricated beef.

Furthermore, LeBrandon pointed to the ever controversial usage of AI in Hip Hop, something Drake’s boss, Sir Lucian Grainge, recently condemned (especially when Drake, himself, condemns the AI usage of his own voice). By blatantly ignoring the issues and respectability codes the Hip Hop community should and does have with these ideas, Drake’s method of poking fun at his opponent was glorious. It was uncomfortable, condescending and straight-up gangsta. It also showcased Drake’s everlasting creative ability and willingness to take a risk. Todd acknowledged a generationally tinged viewpoint: this might also be a misstep for Drake because he used Snoop Dogg’s voice as well. Not only is Snoop alive, but Snoop was instrumental in passing the West Coast torch and crown to Kendrick. So when Drake uses an AI Snoop voice to spit “right now it’s looking like you writin’ out the game plan on how to lose/ how to bark up the wrong tree and then get your head popped in a crowded room,” it strikes at the heart of the AI controversy in music. This was not Snoop’s commentary at all. We both agree, however, that the “bark up the wrong tree” and “Kendrick we need ya” lines came back to haunt Drake. We also agree that dropping “Push Ups” and “Taylor Made Freestyle” is Drake’s battle format, hoping that he can overwhelm an opponent with multiple songs in rapid fire.

Todd and LeBrandon’s Hip Hop History Month play-by-play continues on November 11th with the release of Part 2! Return for “Euphoria” and stay until “6:16 in LA.”

—

Our Icon for this series is a mash up of “Kendrick Lamar (Sziget Festival 2018)” taken by Flickr User Peter Ohnacker (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) and “Drake, Telenor Arena 2017” taken by Flickr User Kim Erlandsen, NRK P3 (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

—

Todd Craig (he/him) is a writer, educator and DJ whose career meshes his love of writing, teaching and music. His research inhabits the intersection of writing and rhetoric, sound studies and Hip Hop studies. He is the author of “K for the Way”: DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies (Utah State University Press) which examines the Hip Hop DJ as twenty-first century new media reader, writer, and creator of the discursive elements of DJ rhetoric and literacy. Craig’s publications include the multimodal novel tor’cha (pronounced “torture”), and essays in various edited collections and scholarly journals including The Bloomsbury Handbook of Hip Hop Pedagogy, Amplifying Soundwriting, Methods and Methodologies for Research in Digital Writing and Rhetoric, Fiction International, Radical Teacher, Modern Language Studies, Changing English, Kairos, Composition Studies and Sounding Out! Dr. Craig teaches courses on writing, rhetoric, African American and Hip Hop Studies, and is the co-host of the podcast Stuck off the Realness with multi-platinum recording artist Havoc of Mobb Deep. Presently, Craig is an Associate Professor of African American Studies at New York City College of Technology and English at the CUNY Graduate Center.

LeBrandon Smith (he/him) is a cultural curator and social impact leader born and raised in Brooklyn and Queens, respectively. Coming from New York City, his efforts to bridge gaps, and build community have been central to his work, but most notably his passion for music has fueled his career. His programming has been seen throughout the Metropolitan area, including historical venues like Carnegie Hall, The Museum of the City of NY (MCNY) and Brooklyn Public Library.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“Heavy Airplay, All Day with No Chorus”: Classroom Sonic Consciousness in the Playlist Project—Todd Craig

SO! Reads: “K for the Way”: DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies—DeVaughn (Dev) Harris

Caterpillars and Concrete Roses in a Mad City: Kendrick Lamar’s “Mortal Man” Interview with Tupac Shakur–Regina Bradley

In Search of Politics Itself, or What We Mean When We Say Music (and Music Writing) is “Too Political”

Music has become too political—this is what some observers said about the recent Grammy Awards. Following the broadcast last week, some argued that musicians and celebrities used the event as a platform for their own purposes, detracting from the occasion: celebration of music itself. Nikki Haley, the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, tweeted:

I have always loved the Grammys but to have artists read the Fire and Fury book killed it. Don’t ruin great music with trash. Some of us love music without the politics thrown in it.— Nikki Haley (@nikkihaley) January 29, 2018

I don’t know for sure, but I imagine that the daily grind of a U.N. ambassador is filled with routine realities we refer to as “politics”: bureaucracy, budget planning, hectic meetings, and all kinds of disagreements. It makes some sense to me, then, that Haley would demand a realm of life that is untouched by politics—but why music in particular?

The fantasy of a space free from politics resembles other patterns of utopian thought, which often take the form of nostalgia. “There was a time when only a handful of people seemed to write politically about music,” said Chuck Klosterman, a novelist and critic of pop culture, in an interview in June 2017. He continued:

Now everybody does, so it’s never interesting. Now, to see someone only write about the music itself is refreshing. It’s not that I don’t think music writing should have a political aspect to it, but when it just becomes a way that everyone does something, you see a lot of people forcing ideas upon art that actually detracts [sic] from the appreciation of that art. It’s never been worse than it is now.

He closed his interview by saying: “I do wonder if in 15 years people are going to look back at the art from this specific period and almost discover it in a completely new way because they’ll actually be consuming the content as opposed to figuring out how it could be made into a political idea.” Klosterman almost said it: make criticism great again.

Reminiscing about a time when music writing was free from politics, Klosterman suggests that critics can distinguish between pure content and mere politics—which is to say, whatever is incidental to the music, rather than central to it. He offers an example, saying, “My appreciation of [Merle Haggard’s] ‘Workin’ Man Blues’ is not really any kind of extension of my life, or my experience, or even my values. […] I can’t describe why I like this song, I just like it.” If Klosterman, an accomplished critic, tried to describe the experiences that lead him to like this particular song, he probably could—but the point is that he doesn’t make explicit the relationship between personal identity and musical taste.

Screen Capture of Merle Haggard singing “Workin’ Man Blues,” Live from Austin, Texas, 1978

The heart of Klosterman’s concern is that critics project too many of their own problems and interests onto musicians. Musician and music writer Greg Tate recently made a similar suggestion: when reviewing Jay-Z’s album 4:44, Tate focuses on how celebrities become attached to public affects. In his July 2017 review, “The Politicization of Jay-Z,” he writes:

In the rudderless free fall of this post-Obama void […] all eyes being on Bey-Z, Kendrick, and Solange makes perfect agitpop sense. All four have become our default stand-ins until the next grassroots groundswell […] Bey-Z in particular have become the ready-made meme targets of everything our online punditry considers positive or abhorrent about Blackfolk in the 21st century.

Jay and Bey perform live in 2013, by Flickr user sashimomura,(CC BY 2.0)

He suggests that critics politicize musicians, turning them into repositories of various projections about the culture-at-large. Although writing from a very different place than Klosterman, Tate shares the sense that most music criticism is not really about music at all. But whereas Klosterman implies that criticism resembles ideological propaganda too much, Tate implies that criticism is a mere “stand-in” for actual politics, written at the expense of actual political organizing. In other words, music criticism is not political enough.

In 1926, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote about this problem, the status of art as politics. In his essay “Criteria of Negro Art,” he dissects what he perceives to be the hypocrisy of any demand for pure art, abstracted from politics; he defends art that many others would dismiss as propagandistic—a dismissal revealed to be highly racialized. He writes:

Thus all Art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists. I stand in utter shamelessness and say that whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of black folk to love and enjoy. I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda. But I do care when propaganda is confined to one side while the other is stripped and silent.

Du Bois’s ideas would be engaged extensively by later authors, including Amiri Baraka. In his 1963 essay “Jazz and the White Critic,” he addresses politics in terms of “attitude.” Then-contemporary white critics misunderstood black styles, he argued, because they failed to fully apprehend the attitudes that produced them. They were busy trying, and failing, to appreciate the sound of bebop “itself,” but without considering why bebop was made in the first place.

Dizzy Gillespie, one of BeBop’s key players, in Paris, 1952, Image courtesy of Flickr User Kristen, (CC BY 2.0)

As Baraka presents it, white critics were only able to ignore black musicians’ politics and focus on the music because the white critics’ own attitudes had already been assumed to be superior, and therefore rendered irrelevant. Only because their middle-brow identities had been so thoroughly elevated in history could these middle-brow critics get away with defining the object of their appreciation as “pure” music. Interestingly, as Baraka concludes, it was their ignorance of context that ultimately served to “obfuscate what has been happening with the music itself.” It’s not that the music itself doesn’t matter; it’s that music’s context makes it matter.

In response to morerecent concerns about the politicization of popular music, Robin James has analyzed the case of Beyoncé’s Lemonade. She performs a close reading of two reviews, by Carl Wilson and by Kevin Fallon, both of whom expressly seek the album’s “music itself,” writing against the many critical approaches that politicize it. James suggests that these critics can appeal to “music itself” only because their own identities have been falsely universalized and made invisible. They try to divorce music from politics precisely because this approach, in her words, “lets white men pop critics have authority over black feminist music,” a quest for authority that James considers a form of epistemic violence.

That said, James goes on to conclude that the question these critics ask—“what about the music?”—can also be a helpful starting point, from which we can start to make explicit some types of knowledge that have previously remained latent. The mere presence of the desire for a space free from politics and identity, however problematic, tells us something important.

Our contemporary curiosity about identity—identity being our metonym for “politics” more broadly—extends back at least to the 1990s, when music’s political status was widely debated in terms of it. For example, in a 1991 issue of the queercore zine Outpunk, editor Matt Wobensmith describes what he perceived to be limitations of thinking about music within his scene. He laments what he calls “musical purism,” a simplistic mindset by which “you are what you listen to.” Here, he capitalizes his points of tension:

Our contemporary curiosity about identity—identity being our metonym for “politics” more broadly—extends back at least to the 1990s, when music’s political status was widely debated in terms of it. For example, in a 1991 issue of the queercore zine Outpunk, editor Matt Wobensmith describes what he perceived to be limitations of thinking about music within his scene. He laments what he calls “musical purism,” a simplistic mindset by which “you are what you listen to.” Here, he capitalizes his points of tension:

Suddenly, your taste in music equates you with working class politics and a movement of the disenfranchised. Your IDENTITY is based on how music SOUNDS. How odd that people equate musical chops with how tough or revolutionary you may be! Music is a powerful language of its own. But the music-as-identity idea is a complete fiction. It makes no sense and it defies logic. Will someone please debunk this myth?

Wobensmith suggests that a person’s “musical chops,” their technical skills, have little to do with their personal identity. Working from the intersection of Klosterman and Tate, Wobensmith imagines a scenario in which the abstract language of music transcends the identities of the people who make it. Like them, Wobensmith seems worried that musical judgments too often unfold as critiques of a musician’s personality or character, rather than their work. Critics project themselves onto music, and listeners also get defined by the music they like, which he finds unsettling.

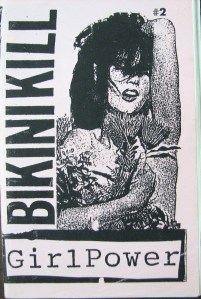

That same year, in an interview published in the 1991 issue of the zine Bikini Kill, musicians Kathleen Hanna and Jean Smith addressed a similar binary as Wobensmith, that of content and technique. But they take a different view: in fact, they emphasize the fallacy of this dualism in the first place. “You just can’t separate it out,” said Hanna, questioning the possibility of distinguishing between content—the “music itself”—and technique on audio recordings.

That same year, in an interview published in the 1991 issue of the zine Bikini Kill, musicians Kathleen Hanna and Jean Smith addressed a similar binary as Wobensmith, that of content and technique. But they take a different view: in fact, they emphasize the fallacy of this dualism in the first place. “You just can’t separate it out,” said Hanna, questioning the possibility of distinguishing between content—the “music itself”—and technique on audio recordings.

Female-fronted bands of this era were sometimes criticized for their lack of technique, even as terrible male punk bands were widely admired for their cavalier disregard of musical rules. Further still, disparagement of women’s poor technique often overlooked the reasons why it suffered: many women had been systematically discouraged from musical participation in these scenes. Either way, as Tamra Lucid has argued, it is the enforcement of “specific canons of theory and technique,” inevitably along the lines of identity, that cause harm if left unexamined.

All of these thinkers show that various binaries in circulation—sound and identity, personality and technique, music and politics—are gendered in insidious ways, an observation arrived at by the same logic that led Du Bois to reveal the moniker of “propaganda” to be racialized. As Hanna puts it, too many people assumed that “male artists are gonna place more importance on technique and female artists’ll place more on content.” She insists that these two concepts can’t be separated in order to elevate aspects of experience that had been implicitly degraded as feminine: the expression of righteous anger, or recollection of awkward intimacy.

Bikini Kill at Gilman Street, Berkeley, CA, 1990s, Image by Flickr User John Eikleberry, CC BY-NC 2.0

Punk had never pretended not to be political, making it a powerful site for internal critique. Since the 1970s, punk had been a form in which grievances about systemic problems and social inequality could be openly, overtly aired. The riot grrrls, by politicizing confessional, femme, and deeply private forms of expression within punk, demonstrated that even the purest musical politics resemble art more than is sometimes thought: “politics itself” is necessarily performative, personal, and highly expressive, involving artifice.

Even the act of playing music can be considered a form of political action, regardless of how critics interpret it. In another punk zine from c. 1990, for example, an anonymous author asks:

What impact can music have? You could say that it’s always political, because a really good pop song, even when it hasn’t got political words, is always about how much human beings can do with the little bag of resources, the limited set of playing pieces and moves and words, available […] Greil Marcus calls it ‘the vanity of believing that cheap music is potent enough to take on nothingness,’ and it may be cool in some places to mock him but here he’s dead-on right.

But music is never only political—that is, not in the elections-and-petitions sense of the word. And music is always an action, always something done to listeners, by musicians (singers, songwriters, producers, hissy stereo systems)—but it’s never only that, when it’s any good: no more than you, reader, are the social roles you play.

The author persuades us that music is political, even as they insist that it’s something more. Music as “pure sound,” as a “universal language” seems to have the most potential to be political, but also to transcend politics’ limitations—the trash, the propaganda. Given this potential, some listeners find themselves frustrated with music’s consistent failure to rise to their occasion, to give them what they desire: to be apolitical.

Kelly Clarkson performed at The Chelsea on July 27, 2012, image by Flickr User The Cosmopolitan of Las Vegas, CC BY-NC 2.0

In an interview during the recent Grammys broadcast, pop singer Kelly Clarkson said, “I’m political when I feel like I need to be.” It’s refreshing to imagine politics this way, like a light we turn on and off–and it’s a sign of political privilege to be able to do so. But politics are, unfortunately, inextricable from our lives and therefore inescapable: the places we go, the exchanges we pursue, the relationships we develop, the ways we can be in the world. Thinking with Robin James, it seems that our collective desire for a world free from all this reveals a deeper knowledge, which music helps make explicit: we wish things were different.

I wonder if those who lament the “contamination” of the Grammys with politics might be concerned that their own politics are unfounded or irrelevant, requiring revision, just as many white people who are allergic to identity politics are, in fact, aware that our own identity has been, and continues to be, unduly elevated. When Chuck Klosterman refuses to describe the reason why he likes “Workin’ Man Blues,” claiming that he “just does,” does he fear, as I sometimes do, not that there is no reason, but that this reason isn’t good enough?

Fortunately, there are many critics today who do the difficult work of examining music’s politics. Take Liz Pelly, for example, whose research about the backend of streaming playlists reminds us of music’s material basis. Or what about the astute criticism of Tim Barker, Judy Berman, Shuja Haider, Max Nelson, and others for whom musical thought and action are so thoroughly intertwined? Finally, I think of many music writers at Tiny Mix Tapes, such as Frank Falisi, Hydroyoga, C Monster, or Cookcook, for whom creation is a way of life—and whose creative practices themselves are potent enough to “take on nothingness.”

“Music is never only political,” as the anonymous ‘zine article author argues above, but it is always political, at least a little bit. As musicians and critics, our endeavor should not be to transcend this fact, but to affirm it with increasing nuance and care. During a recent lecture, Alexander Weheliye challenged us in a lecture given in January 2018 at New York University, when listening, “To really think: what does this art reflect?” Call it music or call it politics: the best of both will change somebody’s mind for real, and for the better.

—

Featured Image: Screen Capture from Kendrick Lamar’s video for “HUMBLE,” winner of the 2018 Grammy for “Best Music Video.”

—

Elizabeth Newton is a doctoral candidate in musicology. She has written for The New Inquiry, Tiny Mix Tapes, Real Life Magazine, the Quietus, and Leonardo Music Journal. Her research interests include musico-poetics, fidelity and reproduction, and affective histories of musical media. Her dissertation, in progress, is about “affective fidelity” in audio and print culture of the 1990s.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

SO! Reads: Jace Clayton’s Uproot–Elizabeth Newton

Re: Chuck Klosterman – “Tomorrow Rarely Knows”–Aaron Trammell

This is What It Sounds Like . . . . . . . . On Prince (1958-2016) and Interpretive Freedom–Ben Tausig

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- SO! Reads: Alexis McGee’s From Blues To Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics

- SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

- Impaulsive: Bro-casting Trump, Part I

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments