Beyond the Every Day: Vocal Potential in AI Mediated Communication

In summer 2021, sound artist, engineer, musician, and educator Johann Diedrick convened a panel at the intersection of racial bias, listening, and AI technology at Pioneerworks in Brooklyn, NY. Diedrick, 2021 Mozilla Creative Media award recipient and creator of such works as Dark Matters, is currently working on identifying the origins of racial bias in voice interface systems. Dark Matters, according to Squeaky Wheel, “exposes the absence of Black speech in the datasets used to train voice interface systems in consumer artificial intelligence products such as Alexa and Siri. Utilizing 3D modeling, sound, and storytelling, the project challenges our communities to grapple with racism and inequity through speech and the spoken word, and how AI systems underserve Black communities.” And now, he’s working with SO! as guest editor for this series for Sounding Out! (along with ed-in-chief JS!). It starts today, with Amina Abbas-Nazari, helping us to understand how Speech AI systems operate from a very limiting set of assumptions about the human voice– are we training it, or is it actually training us?

—

Hi, good morning. I’m calling in from Bangalore, India.” I’m talking on speakerphone to a man with an obvious Indian accent. He pauses. “Now I have enabled the accent translation,” he says. It’s the same person, but he sounds completely different: loud and slightly nasal, impossible to distinguish from the accents of my friends in Brooklyn.

The AI startup erasing call center worker accents: is it fighting bias – or perpetuating it? (Wilfred Chan, 24 August 2022)

This telephone interaction was recounted in The Guardian reporting on a Silicon Valley tech start-up called Sanas. The company provides AI enabled technology for real-time voice modification for call centre workers voices to sound more “Western”. The company describes this venture as a solution to improve communication between typically American callers and call centre workers, who might be based in countries such as Philippines and India. Meanwhile, research has found that major companies’ AI interactive speech systems exhibit considerable racial imbalance when trying to recognise Black voices compared to white speakers. As a result, in the hopes of being better heard and understood, Google smart speaker users with regional or ethnic American accents relay that they find themselves contorting their mouths to imitate Midwestern American accents.

These instances describe racial biases present in voice interactions with AI enabled and mediated communication systems, whereby sounding ‘Western’ entitles one to more efficient communication, better usability, or increased access to services. This is not a problem specific to AI though. Linguistics researcher John Baugh, writing in 2002, describes how linguistic profiling is known to have resulted in housing being denied to people of colour in the US via telephone interactions. Jennifer Stoever‘s The Sonic Color Line (2016) presents a cultural and political history of the racialized body and how it both informed and was informed by emergent sound technologies. AI mediated communication repeats and reinforces biases that pre-exist the technology itself, but also helping it become even more widely pervasive.

Mozilla’s commendable Common Voice project aims to ‘teach machines how real people speak’ by building an open source, multi-language dataset of voices to improve usability for non-Western speaking or sounding voices. But singer and musicologist, Nina Sun Eidsheim describes how ’a specific voice’s sonic potentiality [in] its execution can exceed imagination’ (7), and voices as having ‘an infinity of unrealised manifestations’ (8) in The Race of Sound (2019). Eidsheim’s sentiments describe a vocal potential, through musicality, that exists beyond ideas of accents and dialects, and vocal markers of categorised identity. As a practicing vocal performer, I recognise and resonate with Eidsheim’s ideas I have a particular interest in extended and experimental vocality, especially gained through my time singing with Musarc Choir and working with artist Fani Parali. In these instances, I have experienced the pleasurable challenge of being asked to vocalise the mythical, animal, imagined, alien and otherworldly edges of the sonic sphere, to explore complex relations between bodies, ecologies, space and time, illuminated through vocal expression.

Following from Eidsheim, and through my own vocal practice, I believe AI’s prerequisite of voices as “fixed, extractable, and measurable ‘sound object[s]’ located within the body” is over-simplistic and reductive. Voices, within systems of AI, are made to seem only as computable delineations of person, personality and identity, constrained to standardised stereotypes. By highlighting vocal potential, I offer a unique critique of the way voices are currently comprehended in AI recognition systems. When we appreciate the voice beyond the homogenous, we give it authority and autonomy, ultimately leading to a fuller understanding of the voice and its sounding capabilities.

My current PhD research, Speculative Voicing, applies thinking about the voice from a musical perspective to the sound and sounding of voices in artificially intelligent conversational systems. Herby the voice becomes an instrument of the body to explore its sonic materiality, vocal potential and extremities of expression, rather than being comprehended in conjunction to vocal markers of identity aligning to categories of race, gender, age, etc. In turn, this opens space for the voice to be understood as a shapeshifting, morphing and malleable entity, with immense sounding potential beyond what might be considered ordinary or everyday speech. Over the long term this provides discussion of how experimenting with vocal potential may illuminate more diverse perspectives about our sense of self and being in relation to vocal sounding.

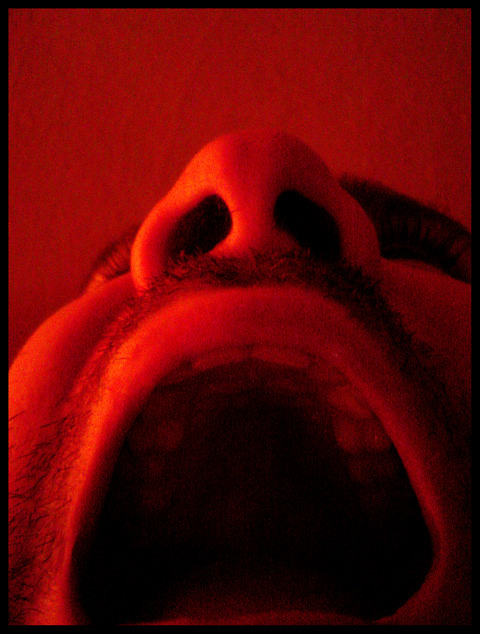

Vocal and movement artist Elaine Mitchener exhibits the disillusion of the voice as ‘fixed’ perfectly in her performance of Christian Marclay’s No!, which I attended one hot summer’s evening at the London Contemporary Music Festival in 2022. Marclay’s graphic score uses cut outs from comic book strips to direct the performer to vocalise a myriad of ‘No”s.

Mitchener’s rendering of the piece involved the cooperation and coordination of her entire body, carefully crafting lips, teeth, tongue, muscles and ligaments to construct each iteration of ‘No.’ Each transmutation of Mitchener’s ‘No’s’ came with a distinct meaning, context, and significance, contained within the vocalisation of this one simple syllable. Every utterance explored a new vocal potential, enabled by her body alone. In the context of AI mediated communication, we can see this way of working with the voice renders the idea of the voice as ‘fixed’ as redundant. Mitchener’s vocal potential demonstrates that voices can and do exist beyond AI’s prescribed comprehension of vocal sounding.

In order to further understand how AI transcribes understandings of voice onto notions of identity, and vocal potential, I produced the practice project Polyphonic Embodiment(s) as part of my PhD research, in collaboration with Nestor Pestana, with AI development by Sitraka Rakotoniaina. The AI we created for this project is based upon a speech-to-face recognition AI that aims to be able to tell what your face looks like from the sound of your voice. The prospective impact of this AI is deeply unsettling, as its intended applications are wide-ranging – from entertainment to security, and as previously described AI recognition systems are inherently biased.

This multi-modal form of comprehending voice is also a hot topic of research being conducted by major research institutions including Oxford University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. We wanted to explore this AI recognition programme in conjunction with an understanding of vocal potential and the voice as a sonic material shaped by the body. As the project title suggests, the work invites people to consider the multi-dimensional nature of voice and vocal identity from an embodied standpoint. Additionally, it calls for contemplation of the relationships between voice and identity, and individuals having multiple or evolving versions of identity. The collaboration with the custom-made AI software creates a feedback loop to reflect on how peoples’ vocal sounding is “seen” by AI, to contest the way voices are currently heard, comprehended and utilised by AI, and indeed the AI industry.

The video documentation for this project shows ‘facial’ images produced by the voice-to-face recognition AI, when activated by my voice, modified with simple DIY voice devices. Each new voice variation, created by each device, produces a different outputted face image. Some images perhaps resemble my face? (e.g. Device #8) some might be considered more masculine? (e.g. Device #10) and some are just disconcerting (e.g. Device #4). The speculative nature of Polyphonic Embodiment(s) is not to suggest that people should modify their voices in interaction with AI communication systems. Rather the simple devices work with bodily architecture and exaggerate its materiality, considering it as a flexible instrument to explore vocal potential. In turn this sheds light on the normative assumptions contained within AI’s readings of voice and its relationships to facial image and identity construction.

Through this artistic, practice-led research I hope to evolve and augment discussion around how the sounding of voices is comprehended by different disciplines of research. Taking a standpoint from music and design practice, I believe this can contest ways of working in the realms of AI mediated communication and shape the ways we understand notions of (vocal) identity: as complex, fluid, malleable, and ultimately not reducible to Western logics of sounding.

—

Featured Image: Still image from Polyphonic Embodiments, courtesy of author.

—

Amina Abbas-Nazari is a practicing speculative designer, researcher, and vocal performer. Amina has researched the voice in conjunction with emerging technology, through practice, since 2008 and is now completing a PhD in the School of Communication at the Royal College of Art, focusing on the sound and sounding of voices in artificially intelligent conversational systems. She has presented her work at the London Design Festival, Design Museum, Barbican Centre, V&A, Milan Furniture Fair, Venice Architecture Biennial, Critical Media Lab, Switzerland, Litost Gallery, Prague and Harvard University, America. She has performed internationally with choirs and regularly collaborates with artists as an experimental vocalist

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

What is a Voice?–Alexis Deighton MacIntyre

Voice as Ecology: Voice Donation, Materiality, Identity–-Steph Ceraso

Mr. and Mrs. Talking Machine: The Euphonia, the Phonograph, and the Gendering of Nineteenth Century Mechanical Speech – J. Martin Vest

One Scream is All it Takes: Voice Activated Personal Safety, Audio Surveillance, and Gender Violence—María Edurne Zuazu

Echo and the Chorus of Female Machines—AO Roberts

On Sound and Pleasure: Meditations on the Human Voice– Yvon Bonefant

Teaching Soundwalks in a Course on Gentrification, Black Music, and Corporate America

On May 5, 2018, the C-ville Weekly, a newspaper based out of Charlottesville, Virginia, published an article titled “Sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll: new apartment complex promises at least one of those.” The headline referred to the complex being built at 600 West Main St. in Charlottesville. The complex has since been completed and studio bedrooms currently cost more than $1000 a month. As the C-ville Weekly headline shows, the developers were using the term and connotations of “rock ’n’ roll” to sell exclusive – and in many ways unaffordable – housing.

After reading this headline, I began to develop an idea for a summer course at my institution, the University of Virginia (UVA). I ultimately titled that course “Black Music and Corporate America” which I offered online during the summer of 2021 (syllabus available for download via the link above). Although the course discussed varied content – from the multi-ethnic, multi-racial, and multi-gendered histories of rock and roll to the endorsement of conspicuous forms of consumption in hip hop – I wanted to spend one unit focusing on the interrelationship between music, corporate America, and gentrification. I strove to solidify this connection by assigning two related articles. The first article, by geographer and sociologist Brandi Thomson Summers, argues that black residents in Washington D.C. adopt go-go music as a form of reclamation aesthetics to combat their city’s increasingly rampant gentrification. In the second article, ethnomusicologist Allie Martin conducts a soundwalk of D.C.’s Shaw District to forefront the experience of a black woman in the city and help displace white hearing as the default standard of interpreting sound (see Sounding Out!’s Soundwalking While POC series from Fall 2019). These two articles served as a foundation for one of the assignments the students had to complete in class: conducting a soundwalk of their own in which they had to walk around a field site of their choosing and think critically about the sounds they were hearing.

Throughout the summer sessions, students completed three main assignments related to the course topic. They had to think about marketing themselves and thus wrote a cover letter for a job or internship they were interested in pursuing in the future. We also, as a class, sent a suggestion to literary scholar John Patrick Leary, who has created a list of “keywords of capitalism:” buzzwords that get adopted in corporate lingo; we suggested “rockstar” as a term and offered him a brief explanation why:

Students also had to conduct a soundwalk. I asked them to model it after Martin’s and to also take into consideration Summers’ arguments about gentrification, white policing of black sound, and a community’s response to attempts to silence their music and culture.

The soundwalks I received merit sharing with readers of Sounding Out for three primary reasons: 1) The assignment benefited from the online format, especially since students could conduct soundwalks in Charlottesville as well as in their homes across the country. 2) the students made compelling arguments that deserve recognition. 2) the students brought up issues that teachers interested in assigning soundwalks in the future might want to preemptively address.

Students who walked around Charlottesville focused mostly on The Corner, the portion of the city where most of UVA’s student body eats, shops, and drinks. As one student noted, during the regular semester, hundreds of students populating The Corner on any given day during the semester can silence out – literally – the concerns of the homeless and the panhandlers who make the area their home. However, over the summer, Charlottesville’s Corner becomes significantly less populated and, as this student noted, much more silent. As a result of this silence, pedestrians might be much more attuned to Charlottesville’s rampant inequality. This student, over the course of their summer soundwalk on The Corner, came to a radical conclusion: while communities might need moratoriums on evictions, or moratoriums on construction, maybe Charlottesville needs a moratorium on student noise as well.

In addition to focusing on inequality, many students’ soundwalks pointed out discrepancies between what they saw and what they heard while on their soundwalks. Another student writing about The Corner noted how, as a transfer student, the music that they heard emanating from a barbershop helped make them feel at home in Charlottesville. Businesses on The Corner have historically not been entirely welcoming to people of color. Additionally, most pedestrians and patrons of The Corner are white. However, this student remarked how comfortable they felt on The Corner because they could hear one of their favorite artists, Moneybagg Yo, playing from the sound system of the barbershop they were going to visit. Long before they could visually see the business, the soundscape let this student know they were welcome. In this way, this barbershop helped create a sense of community in a similar way that the broadcasting of go-go music from Shaw’s many businesses helps create in Washington D.C.

Another student focused specifically on the contradictions between the activism they “saw” demonstrated in their upper-class Boston suburb and the activism they “heard” while walking around their neighborhood. This student noted that residents of their neighborhood strove to create an inclusive atmosphere by putting up “Black Lives Matters” and “Immigrants Welcome” yard signs. However, they also cited Jennifer Lynn Stoever’s work – who we read in class – and noted the presence of what Stoever calls the “sonic color line.” As this students’ own field recordings of their neighborhood illuminated, most residents of this neighborhood valued silence. Harlemites during the 1940s and 1950s, as Stoever writes, certainly appreciated restful nights, but her scholarship also demonstrates how dominant narratives constructed black communities as “noisy,” “chaotic,” and “dangerous,” and white ones as “silent,” “efficient,” and “disciplined.” Although residents in this Boston suburb think of themselves as progressive and demonstrate their liberalism through visual signifiers such as yard signs, this student concluded that they still live in a community that privileges certain (silent) soundscapes. In doing so, such communities continue to perpetuate the sonic color line.

Admittedly, several students living in America’s suburbs struggled to conceive of the sounds they heard as worthy of discussion. For instance, the sounds of cars made frequent appearances in their writing but were often dismissed as inconsequential. Instead, students lamented that they were not experiencing a vibrant public sphere that resembled the setting of Spike Lee’s 1989 film, Do the Right Thing (a film we watched together in class), as if that representation wasn’t a very particular historicized and localized representation. On an individual basis, I tried to get students to think more critically about the sounds of cars in their neighborhood. We read about the role of automobile in the development of G-Funk during the early 1990s as well as the death of Jordan Davis, who was murdered in his car for playing rap too loudly. However, neither article resonated with students’ experience on their soundwalks since they were simply hearing cars passing by their houses or driving down the street. Most of the time, they could not tell what type of music was being listened to at all inside the car nor could they hear it emanate onto the street.

Therefore, teachers, depending on the living conditions of their students, might want to preemptively include discussions of car culture within American society. After all, more than go-go music broadcasted from storefronts, or second line parades, or music playing from boomboxes, or the noise of nature, (my) students typically hear cars in their day-to-day life. As a result, teachers assigning soundwalks may want to talk about the role of highway construction and the automobile industry on suburbanization and white flight. Discussions of automobiles within the context of environmental racism might also be useful for students to consider. Steph Ceraso’s Sounding Composition also discusses the immense time and energy corporations have devoted to car sounds and soundscapes within cars, buffering occupants from car noise as well as that of the neighborhoods outside.

In addition, I found that students need a more robust historical understanding of suburbanization in the United States, particularly alongside an understanding of their own racial and ethnic histories. Some students living African American suburbs could have benefited from some contextualization about when and how they came to be. Talking about suburbanization in general, the development of White suburban liberalism in the 1970s and 1980s would have helped the student living in a Boston suburb make more sense of the politics of their neighborhood. Karen Tongson’s Relocations also provides context for shifts in America’s suburban landscape after sweeping changes in immigration law in 1965, as well as a rethinking of expressions of sexuality in the suburbs. These are just some topics I wish I had focused on more to help prepare my students for their soundwalks.

Future teachers may feel inclined to refer to the conclusions my students came to, as well as the literature I wish I had included in course, as they think about assigning soundwalks in their own classes. Both my students and I appreciated the soundwalk assignment and its invitations to listen differently. Teaching soundwalks in a course focusing on “Black music and marketing strategy” prompted my own necessary meditation as a non-Black scholar working in this field. Guided by Loren Kajikawa’s new research on “Music, Hip Hop and the Challenge of Significant Difference” that examines how the popularity of courses on black music help subsidize a university’s classical music offerings, I want to incorporate future discussions of Black music as sonic diversity marketing in contemporary higher ed, both at the microlevel of scholarship and the macro- institutional level, which remains far from equitable despite ongoing challenges to its status quo. For students, the soundwalks–in their words–allowed them to learn about themselves and think differently about the area in which they live. They also become more attuned to their surroundings–questioning what makes a neighborhood and for whom?–and how different cultures use their voices where they live, necessary skills for our moment that will help us envision a world beyond it.

—

Featured Image: Wall Mural right next to Bowerbird Bakeshop in Charlottesville, VA, image by Tom Mills, (CC BY-SA 2.0)

—

Rami Toubia Stucky is a PhD candidate at the University of Virginia and scholar of the music of the African diaspora, music of the Americas, commercial culture, intercultural exchange, and music and migration. Sometimes he composes/arranges jazz music and plays drums. He is currently writing a dissertation on the arrival of Brazilian bossa nova to the United States during the 1960s. He runs a personal and professional website dedicated mostly to talking about the songs his sister likes.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig all this good stuff about sound studies pedagogy! Good luck with Fall semester, folks!:

The Sounds of Anti-Anti-Essentialism: Listening to Black Consciousness in the Classroom- Carter Mathes

Making His Story Their Story: Teaching Hamilton at a Minority-serving Institution–Erika Gisela Abad

Deejaying her Listening: Learning through Life Stories of Human Rights Violations– Emmanuelle Sonntag and Bronwen Low

Audio Culture Studies: Scaffolding a Sequence of Assignments– Jentery Sayers

Deep Listening as Philogynoir: Playlists, Black Girl Idiom, and Love–Shakira Holt

“Toward A Civically Engaged Sound Studies, or ReSounding Binghamton”–Jennifer Lynn Stoever

“Heavy Airplay, All Day with No Chorus”: Classroom Sonic Consciousness in the Playlist Project—Todd Craig

SO! Podcast #79: Behind the Podcast: deconstructing scenes from AFRI0550, African American Health Activism – Nic John Ramos and Laura Garbes

Listening to #Occupy in the Classroom–D. Travers Scott

SO! Podcast #71: Everyday Sounds of Resilience and Being: Black Joy at School–Walter Gershon

Sounding Out! Podcast #13: Sounding Shakespeare in S(e)oul– Brooke Carlson

A Listening Mind: Sound Learning in a Literature Classroom–Nicole Brittingham Furlonge

My Voice, or On Not Staying Quiet–Kaitlyn Liu

(Re)Locating Soundscapes of Schooling: Learning to Listen to Children’s Lifeworlds–Cassie J. Brownell

If You Can Hear My Voice: A Beginner’s Guide to Teaching–Caroline Pinkston

Mukbang Cooks, Chews, and Heals – David Lee

SO! Podcast #80: Refugee Realities Miniseries–Steph Ceraso

Recent Comments