Alan Lomax’s Southern Journey and the Sound of Authenticity

Welcome back to 100 Years of Alan Lomax, Sounding Out!‘s series dedicated to remembering, rethinking and challenging our understanding of this crucial figure in folk music history.

Welcome back to 100 Years of Alan Lomax, Sounding Out!‘s series dedicated to remembering, rethinking and challenging our understanding of this crucial figure in folk music history.

In contrast to the first post in the series by Mark Davidson, which looked at how we have branded Alan Lomax, Parker Fishel‘s post considers how Alan Lomax fashioned himself—as both a collector and a publisher of other peoples’ music. The complexity of this task is inherent in the social and political ramifications of “saving” sound by making it “ours,” both in terms of singular ownership of singular recordings that had previously “belonged” to a community as well as the extent to which this practice brought these sounds to the wider culture.

Here, Fishel invites the reader to consider this complicated history that surrounds collecting and copyrighting folk music, what (and whom) the practice has excluded as well current performers who have been inspired by this preservation of our sound culture to perpetuate the practice: making it “theirs” and “ours” once again.

— Guest Editor Tanya Clement

—

The more one listens, views, and reads the work of pioneering folklorist Alan Lomax, the more inscrutable it becomes. Even if we set aside the sheer size and diversity of his collection, we are still left with a set of materials that eludes easy interpretation. Too mainstream for the academics and too academic for the mainstream, Lomax’s defiant, passionate quest to bridge the two worlds pioneered the study of sound as an embodiment of social and community dynamics. Yet in promoting American vernacular culture, Lomax also fashioned himself a folk hero, leaving us a legacy where the collector threatens to overshadow the collection. As arguably the world’s most famous folklorist, Lomax is responsible for much of the sound understood as authentic Americana.

Consider one vignette of many: the “Southern Journey,” a 1959-1960 recording trip that Alan Lomax undertook with Shirley Collins throughout Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia. A world unto itself, the story of the Southern Journey reveals how these tensions shaped Lomax’s work and, to an extent, our understanding of a national cultural heritage.

To begin with, the Southern Journey sounded different than previous collecting trips due to the technological sophistication of the field recording set-up. Starting with a 1933 trip accompanying his father John A. Lomax, Alan Lomax’s previous recording expeditions in the South had relied first on Edison cylinders and then on disc-based recorders that had particular weaknesses in terms of fidelity. Surface noise obfuscated certain frequencies and reminded the listener that his or her experience was mediated. During the Southern Journey though, open reel magnetic tape, excellent microphones, and a mixer were employed to make what Lomax, in his tendency towards self-aggrandizement, claimed to be the “first” stereo field recordings in the South. Whatever the reality, the recordings were early efforts to use stereo in the service of field recording to capture more detail and nuance of a performance and its context.

Writing of the opportunity stereo presented for folklore, Lomax noted that “Folk music which, in its natural setting, is meant to be heard in the round, comes into its own with multi-dimensionality, for more than concert music, designed to project from the stage into an auditorium.” According to this reasoning, a good recording in stereo is more inclusive, grounding the listener’s position inside the soundscape of folklore’s community-based practice.

Yet, by nature folklore recordings have certain limitations. As jazz record producer Orrin Keepnews noted, “Our job is to create what is best described as ‘realism’ — the impression and effect of being real — which may be very different from plain unadorned reality.” This murky dividing line is problematic in the context of ethnographic documentation. In the case of Alan Lomax, it’s further complicated by multiple motivations and goals that transform this line into a shifting set of markers.

Luckily, through diligent scholarship and Lomax’s own documentation, we are fairly aware of how this “realism” tension shaped his recordings in real-time performance and its public reception. Lomax sometimes auditioned performers when arriving in a new area; his book The Land Where The Blues Began (in part an reconstruction of the Southern Journey) was written 30-plus years after the fact from memory and a few scribbled notes on the back of tape boxes. However this knowledge impacts the supposed reality of the field recordings, it would be a mistake to reduce the extensive documentation of Lomax’s decision-making process to debunking. Rather, it is an aid for understanding what we’re hearing. By accounting for ethnographic and popularizing tendencies, what is really being developed is a guide for critical listening.

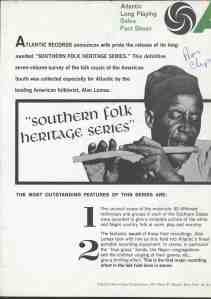

Part of that involved bringing in the recording industry. Starting with the 1939 Musicraft release of Leadbelly performances on 78-RPM discs, Lomax consistently used record companies as one means of bringing folklore to a wider audience. Commenting on the flurry of activity that accompanied Lomax’s 1959 return to the United States after nearly a decade abroad, noted folklorist Roger Abrahams commented, “To this writer it would appear that Mr. Lomax stayed up nights thinking of ways to sell folk-things to publishers, record companies, etc., ergo to the public.”

The Southern Journey was one such project, bankrolled by Atlantic Records. From nearly 80 hours of recorded material, Lomax curated two sets of releases in 1960, a seven LP Atlantic Records collection named the “Southern Folk Heritage Series” and the 12-LP “Southern Journey” series for Prestige International. In notes for reissues of the Atlantic set, Lomax admitted, “The set reflects, to some extent, what the Erteguns [Ahmet and Nesuhi, founders of Atlantic] felt might best reach their pop audience.” Examining how these recordings became canonical is to look at how new modes of cultural transmission affected folklore traditions.

We can hear another tension being negotiated in the way Lomax celebrated performances, which today justly rank alongside those of the Great American Songbook. Yet, to see them that way negates the core strengths of folklore: flexibility to situation and contingency to community. In the field, Lomax asserted that “every performance is original, a fresh and intentionally varied re-creation or rearrangement of a piece.” At the same moment, however, Americanizing processes were transforming these flexible local improvisatory practices into fixed inscriptions of national character. With his public visibility and prestige, the pieces in Lomax’s books and records carried weight as definitive versions – claims Lomax perpetuated in order to unify some of his cultural theories. (It also didn’t hurt that the practice of early folklorists was to copyright these compositions, giving them a financial stake in perpetuating those performances as examples of exceptionalism.) As a result, the public adopted a set of arbitrary songs and sounds as markers of authenticity.

These concerns remain important in the music’s continuing, living traditions. Groups like the Carolina Chocolate Drops or The Ebony Hillbillies perform the full, eclectic spectrum of early African-American string and jug bands traditions. While Jerron ‘Blind Boy’ Paxton forges similar terrain using the African-American songster and blues singer as a model, Frank Fairfield addresses Anglo-American folk traditions. All of these projects remind listeners of the arbitrary divisions of authenticity forced on musicians practices by the race recording industry, which partitioned sounds as white and black and led to our modern taxonomy of genres. These performers use folklore to expose parts of the under-documented past, re-appropriating musical styles and often re-creating that world through the adoption of early 20th century language, clothes, and mannerisms.

Other contemporary performers handle these issues differently. Megafaun, Fight The Big Bull, and Justin Vernon (of Bon Iver) form the nucleus of Sounds of the South, a “loving reinterpretation of the sound, structure, lyrics, and spirit” of the Southern Journey recordings. Engaging both the African-American and Anglo-American traditions documented on that trip, the group finds its sound in their overlap. This a space shaped in part by the popularizing processes Lomax set in motion, a space where generations of listeners have been introduced to Mississippi Fred McDowell through a Rolling Stones cover. Approaching the music from this perspective and not from the background of a Forest City Joe or an Almeda Riddle, authenticity necessarily exists in a different realm: re-interpretation. The resulting arrangements, such as that of Estil C. Ball’s sacred composition “Tribulations,” give one illustration of how these dynamics play out sonically within the world of folklore and music that Lomax left behind.

For this particular piece, the words and melody of Ball’s “terrifying meditation on the end of days” are kept as links to the original recording. This frees the ensemble to follow its muse into the musical landscapes of the intervening 50-plus years, shaped as they were by the introduction of the vernacular into the mainstream (and vice versa). Ball’s melody evokes an archetype, the high lonesome sound of Appalachia; a trope it inspired in the first place. Yet, in this cultural confluence, there is also space for something like Matthew E. White’s soul-influenced electric guitar. In introducing of a style, tradition, and sound beyond the original recording, a color line is crossed that, while maybe not explicitly heard, was certainly present in the Jim Crow context of the Southern Journey. For Sounds of the South, authenticity exists beyond mere re-creation.

What might Lomax’s reaction to the Sounds of the South project be? Reflecting on the 1960s folk scene, Lomax wrote, “The American city folk singer, because he got his songs from books or other city singers, has generally not been aware of the singing style or the emotional content of the folk songs, as they exist in tradition.” On the other hand, Lomax might be heartened that many, whether cultural heritage institutions or record labels, are following in the footsteps of his own Association for Cultural Equity. Working on the scale that digital resources facilitate, these organizations are providing access to field recordings and their context in ways never before possible. (What remains to be seen is how this might impact the process of codification discussed above.)

In another way, the Sounds of the South marks a return to tradition. While the Southern Journey recordings are the primary inspiration, Sounds of the South member Joe Westerlund describes the project as something larger: “We wanted to include everything that we’re into, not just the traditional folk music that’s on this box set…We’re doing our whole experience as musicians.” That experience involves collaboration with folk artists like the Blind Boys of Alabama and Alice Gerrard, as well as investment in their local cultural communities of Durham, NC, Richmond, VA, and Eau Claire, WI.

Alan Lomax (left) with Richard Queen of Soco Junior Square Dance Team at the Mountain Music Festival, Asheville, North Carolina; via the Library of Congress Lomax Collection

Lomax’s pedagogy of folklore situates authenticity as a function of these very types of activities. “Folk song lives in a rather mysterious world close to the heart of the human community and it is only through extended and serious contact with living folk traditions that it can be understood.” The particular tradition in which one participates makes little difference; rather emphasis is on the process of engagement and contact, which replicate older patterns of folklore transmission. So even if Lomax may have claimed there was a bit too much bel canto to suit his tastes, one can imagine his appreciation for Sounds of the South’s dedication to the meaning and spirit of the music.

Considering Alan Lomax, his work, and his legacy is a complex and often frustrating enterprise. Yet amidst parts that give us pause, there remain bits of enduring wisdom. Addressing a gathering of folklorists, Lomax asserted that “Underneath we are all morally, emotionally and esthetically involved with our material, and so all of us are artists and cultural workers, and there is no escape from that.”

Few of us devote ourselves to this kind of music (or any kind of music for that matter) as a detached academic exercise. It can take an example of the living tradition like Sounds of the South looking backwards and forwards to remind us of the full scope of our responsibilities. I can’t think of any more fitting tribute on the occasion of his centenary than to re-commit ourselves not to Alan Lomax, but to what caught his ear in the first place: the transcendent experience of sound.

—

Parker Fishel is an archivist, writer, and researcher living in Brooklyn, New York. Presently he is the archivist at Grey Water Park Productions and an occasional DJ on WKCR-FM. As co-founder of Americana Music Productions, Parker is the producer of a forthcoming set of music, photographs, and scholarship documenting the 1969 Ann Arbor Blues Festival. He is also at work on Georgia Griot, a bio-discography of jazz musician Marion Brown. While getting an MSIS from the University of Texas at Austin, Parker worked with the UT Folklore Center Archives and the John Avery Lomax Family Papers at the Briscoe Center for American History.

—

Featured image: “This Machine Surrounds Hate and Forces It to Surrender” by Flickr user Bee Collins, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“Ain’t Got the Same Soul” — Osvaldo Oyola

On the Lower Frequencies: Norman Corwin, Colorblindness, and the “Golden Age” of U.S. Radio — Jennifer Stoever

Six Years in Nodar: Sound Art in a Rural Context — Rui Costa

Recent Comments