SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests (Penn State University Press) is a book “about the sounds made by those seeking change” (5). It situates these sounds within a broader inquiry into rhetoric as sonic event and sonic action—forms of practice that are collective, embodied, and necessarily relational. It also addresses a long-standing question shared by many of us in rhetorical studies: Where did the sound go? And specifically, in a field that had centered at least half of its disciplinary identity around the oral/aural phenomena of speech, why did the study of sound and rhetoric require the rise of sound studies as a distinct field before it could regain traction?

Eckstein confronts this silence with urgency and clarity, offering a compelling case for how sound operates not just as a sensory experience but as a rhetorical force in public life. By analyzing protest environments where sound is both a tactic and a terrain of struggle, Sound Tactics reinvigorates our understanding of rhetoric’s embodied, affective, and spatial dimensions. What’s more, it serves as an important reminder that sound has always played an important role in studies of speech communication.

Rhetoric emerged in the Western tradition as the study and practice of persuasive speech. From Aristotle through his Greek predecessors and Roman successors, theorists recognized that democratic life required not just the ability to speak, but the ability to persuade. They developed taxonomies of effective strategies—structures, tropes, stylistic devices, and techniques—that citizens were expected to master if they hoped to argue convincingly in court, deliberate in the assembly, or perform in ceremonial life.

We’ve inherited this rhetorical tradition, though, as Eckstein notes early in Sound Tactics, in the academy it eventually splintered into two fields: one that continued to study rhetoric as speech, and another that focused on rhetoric as a writing practice. But somewhere along the way, even rhetoricians with a primary interest in speech moved toward textual representation of speech, rather than the embodied, oral/aural, sonic event that make up speech acts (see pgs 49-50).

Sound Tactics corrects this oversight first by broadening what counts as a “speech act”—not only individual enunciations, but also collective, coordinated noise. Eckstein then offers updated terminology and analytical tools for studying a wide range of sonic rhetorics. The book presents three chapter-length case studies that demonstrate these tools in action.

The first examines the digital soundbite or “cut-out” from X González’s protest speech following the school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. The second focuses on the rhythmic, call-and-response “heckling” by HU Resist during their occupation of a Howard University building in protest of a financial aid scandal. The third analyzes the noisy “Casseroles” retaliatory protests in Québec, where demonstrators banged pots and pans in response to Bill 78’s attempts to curtail public protest.

A full recounting of the book’s case studies isn’t possible here, but they are worth highlighting—not only for the issues Eckstein brings to light, but for how clearly they showcase his analytical tools and methods in action. These methods, in my estimation, are the book’s most significant contribution to rhetorical studies and to scholars more broadly interested in sound analysis.

Eckstein’s analytical focus is on what he calls the “sound tactic,” which is “the sound (adjective) use of sound (noun) in the act of demanding” (2). Soundness in this double sense is both effective and affective at the sensory level. It is rhetoric that both does and is sound work—and soundness can only be so within a particular social context. For Eckstein, soundness is “a holistic assessment of whether an argument is good or good for something” (14). Sound tactics, then, utilize a carefully curated set of rhetorical tools to accomplish specific argumentative ends within a particular social collective or audience capable of phronesis or sound practical judgement (16). Unsound tactics occur when sound ceases to resonate due to social disconnection and breakage within a sonic pathway (see Eckstein’s conclusion, where he analyzes Canadian COVID-19 protests that began with long-haul truck drivers, but lost soundness once it was detached from its original context and co-opted by the far right).

Just as rhetorical studies has benefitted from the influence of sound studies, Eckstein brings rhetorical methods to sound studies. He argues that rhetoric offers a grounding corrective to what he calls “the universalization of technical reason” or “the tendency to focus on the what for so long that we forget to attend to the why” (29). Following Robin James’s The Sonic Episteme: Acoustic Resonance, Neoliberalism, and Biopolitics, he argues that sound studies work can objectify and thus reify sound qua sound, whereas rhetoric’s speaker/audience orientation instead foregrounds sound as crafted composition—shaped by circumstance, structured by power, and animated by human agency. Eckstein finds in sound studies the terminology for such work, drawing together terms such as acousmatics, waveform, immediacy, immersion, and intensity to aid his rhetorical approach. Each name an aspect of the sonic ecology.

Rhetoricians often speak of the “rhetorical situation” or the circumstances that create the opportunity or exigence for rhetorical action and help to define the relationship between rhetor and audience. While the rhetorical action itself is typically concrete and recognizable, the situation itself—which is always in motion—is more difficult to pin down. “Acousmatics” names a similar phenomenon within a sonic landscape. Noise becomes signal as auditors recognize and respond to particular kinds of sound—a process that requires cultural knowledge, attention, and the proverbial ear to hear. A sound’s origins within that situation may be difficult to parse. Acousmastics accounts for sound’s situatedness (or situation-ness) within a diffuse media landscape where listeners discern signal-through-noise, and bring it together causally as a sound body, giving it shape, direction, and purchase. As such a “sound body” has a presence and power that a single auditor may not possess.

Eckstein defines “sound body” as “our imaginative response to auditory cues, painting vivid, often meaningful narratives when the source remains unseen or unknown” (10). And while the sound body is “unbounded,” it “conveys the immediacy, proximity, and urgency typically associated with a physical presence (12). Thus, a sound body (unlike the human bodies it contains) is unseen, but nonetheless contained within rhetorical situations, constitutive of the ways that power, agency, and constraint are distributed within a given rhetorical context. Eckstein’s sound body is thus distinct from recent work exploring the “vocal body” by Dolores Inés Casillas, Sebastian Ferrada, and Sara Hinojos in “The ‘Accent’ on Modern Family: Listening to Vocal Representations of the Latina Body” (2018, 63), though it might be nuanced and extended through engagement with the latter. A focus on the vocal body brings renewed attention to the materialities of the voice—“a person’s speech, such as perceived accent(s), intonation, speaking volume, and word choice” and thus to sonic elements of race, gender, and sexuality. These elements might have been more explicitly addressed and explored in Eckstein’s case studies.

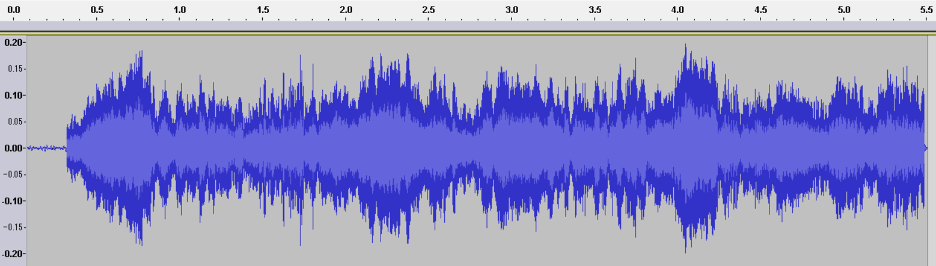

Eckstein uses these terms to help us understand the rhetorical complexities of social movements in our contemporary, digital world—movements that extend beyond the traditional public square into the diverse forms of activism made possible by the digital’s multiplicities. In that framework he offers the “waveform” as a guiding theoretical concept, useful for discerning the sound tactics of social movements. A waveform—the digital, visual representation of a sonic artifact—provides a model for understanding how sound takes shape, circulates, and exerts force. Waveforms also obscure a sound’s originating source and thus act acousmastically.

“[A] waveform is a visual representation of sound that measures vibration along three coordinates: amplitude, frequency, and time” (50). Eckstein draws on the waveform’s “crystallization” of a sonic moment as a metaphor to show sound’s transportability, reproducibility, and flexibility as a media object, and then develops a set of analytical tools for rhetorical analysis that match these coordinates: immediacy, immersion, and intensity. As he describes:

Immediacy involves the relationship between the time of a vibration’s start and end. In any perception of sound, there can be many different sounds starting and stopping, giving the potential for many other points of identification. Immersion encompasses vibration’s capacity to reverberate in space and impart a temporal signature that helps locate someone in an area; think of the difference between an echo in a canyon and the roar of a crowd when you’re in a stadium. Finally, intensity describes the pressure put on a listener to act. Intensity provides the feelings that underwrite the force to compel another to act. Each of these features and the corresponding impact of this experience offer rhetorical intervention potential for social movements. (51)

This toolset is, in my estimation, the book’s most cogent contribution for those working with or interested in sonic rhetorics. Eckstein’s case studies—which elucidate moments of resistance to both broad and incidental social problems—offer clear examples of how these interrelated aspects of the waveform might be brought to bear in the analysis of sound when utilized in both individual and collective acts of social resistance.

To highlight just one example from Eckstein’s three detailed case studies, consider the rhetorical use of immediacy in the chapter titled “The Cut-Out and the Parkland Kid.” The analysis centers on a speech delivered by X González, a survivor of the February 14, 2018, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida. Speaking at a gun control rally in Ft. Lauderdale six weeks after the tragedy, González employed the “cut-out,” a sound tactic that punctuated their testimony with silence.

Embed from Getty Images.

As the final speaker, González reflected on the students lost that day—students who would no longer know the day-to-day pleasures of friendship, education, and the promise of adulthood. The “cut-out” came directly after these remembrances: an extended silence that unsettled the expectations of a live audience disrupting the immediacy of such an event. As the crowd sat waiting, González remained resolute until finally breaking the silence: “Since the time that I came out here, it has been six minutes and twenty seconds […] The shooter has ceased shooting and will soon abandon his rifle, blend in with the students as they escape, and walk free for an hour before arrest” (69–70).

As Eckstein explains, González “needed a way to express how terrifying it was to hide while not knowing what was happening to their friends during a school shooting” (61). By timing the silence to match the duration of the shooting, the focus shifted from the speech itself to an embodied sense of time—an imaginary waveform of sorts that placed the audience inside the terror through what Eckstein calls “durational immediacy.” In this way, silence operated as a medium of memory, binding audience and victims together through shared exposure to the horrors wrought over a short period of time.

…

Sound Tactics is a must-read for those interested in a better understanding of sound’s rhetorical power—and especially how sonic means aid social movements. In conclusion, I would mention one minor limitation of Eckstein’s approach. As much as I appreciated his acknowledgement of sound’s absence from the Communication side of rhetoric, such a proclamation might have benefited from a more careful accounting of sound-related works in rhetorical studies writ large over the last few decades. Without that fuller context, readers may conclude that rhetorical studies has—with a few exceptions—not been engaged with sound. To be fair, the space and focus of Sound Tactics likely did not permit an extended literature review. There is thus an opportunity here to connect Eckstein’s important intervention with the work of other rhetoricians who have also been advancing sound studies.

I am including here a link to a robust (if incomplete) bibliography of sound-related scholarship that I and several colleagues have been compiling, one that reaches across Communication and Writing disciplines and beyond.

—

Featured Image: Family at the CLASSE (Coalition large de l’ASSÉ ) Demonstration in Montreal, Day 111 in 2012 by Flicker User scottmontreal CC BY-NC 2.0

—

Jonathan W. Stone is Associate Professor of Writing and Rhetoric at the University of Utah, where he also serves as Director of First-Year Writing. Stone studies writing and rhetoric as emergent from—and constitutive of—the mythologies that accompany notions of technological advance, with particular attention to sensory experience. His current research examines how the persisting mythos of the American Southwest shapes contemporary and historical efforts related to environmental protection, Indigenous sovereignty, and racial justice, with a focus on how these dynamics are felt, heard, and lived. This work informs a book project in progress, tentatively titled A Sense of Home.

Stone has long been engaged in research that theorizes the rhetorical affordances of sound. He has published on recorded sound’s influence in historical, cultural, and vernacular contexts, including folksongs, popular music, religious podcasts, and radio programs. His open-source, NEH-supported book, Listening to the Lomax Archive, was published in 2021 by the University of Michigan Press and investigates the sonic archive John and Alan Lomax created for the Library of Congress during the Great Depression. Stone is also co-editor, with Steph Ceraso, of the forthcoming collection Sensory Rhetorics: Sensation, Persuasion, and the Politics of Feeling (Penn State U Press), to be published in January 2026.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings –Vanessa Valdés

Quebec’s #casseroles: on participation, percussion and protest–-Jonathan Sterne

SO! Reads: Steph Ceraso’s Sounding Composition: Multimodal Pedagogies for Embodied Listening-–Airek Beauchamp

Faithful Listening: Notes Toward a Latinx Listening Methodology––Wanda Alarcón, Dolores Inés Casillas, Esther Díaz Martín, Sara Veronica Hinojos, and Cloe Gentile Reyes

The Sounds of Equality: Reciting Resilience, Singing Revolutions–Mukesh Kulriya

SO! Reads: Todd Craig’s “K for the Way”: DJ Rhetoric and Literacy for 21st Century Writing Studies—DeVaughn Harris

“Caught a Vibe”: TikTok and The Sonic Germ of Viral Success

“When I wake up, I can’t even stay up/I slept through the day, fuck/I’m not getting younger,” laments Willow Smith of The Anxiety on “Meet Me at Our Spot,” a track released through MSFTSMusic and Roc Nation in March of 2020. Despite the song’s nature as a “sludgy alternative track with emo undertones that hits at the zeitgeist,” “Meet Me at Our Spot” received very little attention after its initial release and did not chart until the summer of 2021, when it went viral on TikTok as part of a dance trend. The short-form video app which exploded in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic, catalyzed the track’s latent rise to success where it reached no. 21 on the US Billboard Hot 100, becoming Willow’s highest charting song since her 2010 hit, “Whip My Hair”.

The app currently known as TikTok began as Musical.ly, which was shuttered in 2017 and then rebranded in 2018. By March of 2021, the app boasted one billion worldwide monthly users, indicative of a growth rate of about 180%. This explosion was in many ways catalyzed by successive lockdowns during the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the relaxation and subsequent abandonment of COVID mitigation measures, the app has retained a large volume of its users, remaining one of the highest grossing apps in the iOS environment. TikTok’s viral success (both as noun and adjective) has worked to create a kind of vibe economy in which artists are now subject to producing a particular type of sound in order to be rendered legible to the pop charts.

For anyone who has yet to succumb to the TikTok trap, allow me to offer you a brief summary of how it functions. Upon opening it, you are instantly fed content. Devoid of any obvious internal operating logic, it is the media equivalent of drinking from a fire hose. Immersive and fast-paced, users vertically scroll through videos that take up their entire screen. Within five minutes of swiping, you can–if your algorithm is anything like mine–see: cute pet videos, protests against police brutality, HypeHouse dance trends, thirst traps, contemporary music, therapy tips, attractive men chopping wood, attractive women lifting weights, and anything else you can fathom. Since its shift from Musical.ly, the app has also been a staging ground for popular music hits such as Lil Nas X’s’ “Old Town Road”, Lizzo’s “Good As Hell”, and, recently, Harry Styles’ “As It Was.”

The app, which is the perfect–if chaotic–fusion of both radio and video is enmeshed in a wider media ecosystem where social networking and platform capitalism converge, and as a result, it seems that TikTok is changing the music industry in at least three distinct ways:

First, it affects our music consumption habits. After hearing a snippet of a song used for a TikTok, users are more likely to queue it up on their streaming platform of choice for another, more complete listen. Unlike those platforms, where algorithms work to feed a listener more of what they’ve already heard, TikTok feeds a listener new content. As a result, there’s no definitive likelihood that you’ve previously heard the track being used as a sound. Therefore, TikTok works the way that Spotify used to: as a mechanism for discovery.

Second, TikTok is changing the nature of the single. Rather than relying upon a label as the engine behind a song’s success, TikTok disseminates tracks–or sounds as they’re referred to in the app–widely, determining a song’s success or role as a debut within a series of clicks. Particularly during the pandemic, when musicians were unable to tour, TikTok’s relationship to the industry became even more salient. Artists sought new ways to share and promote their music, taking to TikTok to release singles, livestream concerts, and engage with fans. Moreover, Spotify’s increasingly capacious playlist archive began to boast a variety of tracklists with titles such as, “Best TikTok Songs 2019-2022”, “TikTok Songs You Can’t Get Out Of Your Head”, and “TikTok Songs that Are Actually Good” among others. The creation and maintenance of this feedback loop between TikTok and Spotify demonstrates not only the centrality of social media ecosystems as driving current popular music success, but also the way that these technologies work in harmony to promote, sustain, or suppress interest in a particular tune.

Most notoriously, the bridge of Olivia Rodrigo’s “drivers license”, went viral as a sound on TikTok in January 2021 and subsequently almost broke the internet. Critics have praised this 24-second section as the highlight of the song, underscoring Rodrigo’s pleading soprano vocals layered over moody, syncopated digital drums. Shortly after it was released, the song shattered Spotify’s record for single-day streams for a non-holiday song. New York Times writer Joe Coscarelli notes of Rodrigo’s success, “TikTok videos led to social media posts, which led to streams, which led to news articles , and back around again, generating an unbeatable feedback loop.”

And third, where songwriting was once oriented towards the creation of a narrative, TikTok’s influence has led artists to a songwriting practice that centers on producing a mood. For The New Yorker, Kyle Chayka argues that vibes are “a rebuke to the truism that people want narratives,” suggesting that the era of the vibe indicates a shift in online culture. He argues that what brings people online is the search for “moments of audiovisual eloquence,” not narrative. Thus, on the one hand, media have become more immersive in order to take us out of our daily preoccupations. On the other, media have taken on a distinct shape so that they can be engaged while doing something else. In other words, media have adapted to an environment wherein the dominant mode of consumption is keyed toward distraction via atmosphere.

Despite their relatively recent resurgence in contemporary discourse, vibes have a rich conceptual history in the United States. Once a shorthand for “vibration” endemic to West Coast hippie vernacular, “vibes” have now come to mean almost anything. In his work on machine learning and the novel form, Peli Grietzer theorizes the vibe by drawing on musician Ezra Koenig’s early aughts blog, “Internet Vibes.” Koenig writes, “A vibe turns out to be something like “local colour,” with a historical dimension. What gives a vibe “authenticity” is its ability to evoke–using a small number of disparate elements–a certain time, place, and milieu, a certain nexus of historic, geographic, and cultural forces.” In his work for Real Life, software engineer Ludwig Yeetgenstein defines the vibe as “something that’s difficult to pin down precisely in words but that’s evoked by a loose collection of ideas, concepts, and things that can be identified by intuition rather than logic.” Where Mitch Thereiau argues that the vibe might just merely be a vocabulary tick of the present moment, Robin James suggests that vibes are not only here to stay, but have in fact been known by many other names before. Black diasporic cultures, in particular, have long believed sound and its “vibrations had the power to produce new possibilities of social attunement and new modes of living,” as Gayle Wald’s “Soul Vibrations: Black Music and Black Freedom in Sound and Space,” attests (674). We might then consider TikTok a key method of dissemination for a maximalist, digital variant of something like Martin Heidegger’s concept of mood (stimmung), or Karen Tongson’s “remote intimacy.” The vibe is both indeterminate and multiple, a status to be achieved and the mood that produces it; vibes seek to promote and diffuse feelings through time and space.

Much current discourse around vibes insists that they interfere with, or even discourage academic interpretation. While some people are able to experience and identify the vibe—perform a vibe check, if you will—vibes defy traditional forms of academic analysis. As Vanessa Valdés points out, “In a post-Enlightenment world that places emphasis on logic and reason, there exists a demand that everything be explained, be made legible.” That the vibe works with a certain degree of strategic nebulousness might in fact be one of its greatest assets.

Vibes resist tidy classification and can thus be named across a variety of circumstances and conditions. Although we might think of the action of ‘vibing’ as embodied, and the term vibration quite literally refers to the physical properties of sound waves and their travel through various mediums, the vibe through which those actions are produced does not itself have to be material. Sometimes, they name a genre of feeling or energy: cursed vibes or cottagecore vibes. Sometimes, they function as a statement of identification: I vibe with that, or in the case of 2 Chainz’s 2016 hit, “it’s a vibe.” Sometimes, vibes are exchanged: you can give one, you can catch one, you can check one, So, while things like energy and mood—which are often taken as cognates for vibes—work to imagine, name, and evoke emotions, vibes are instead invitations.

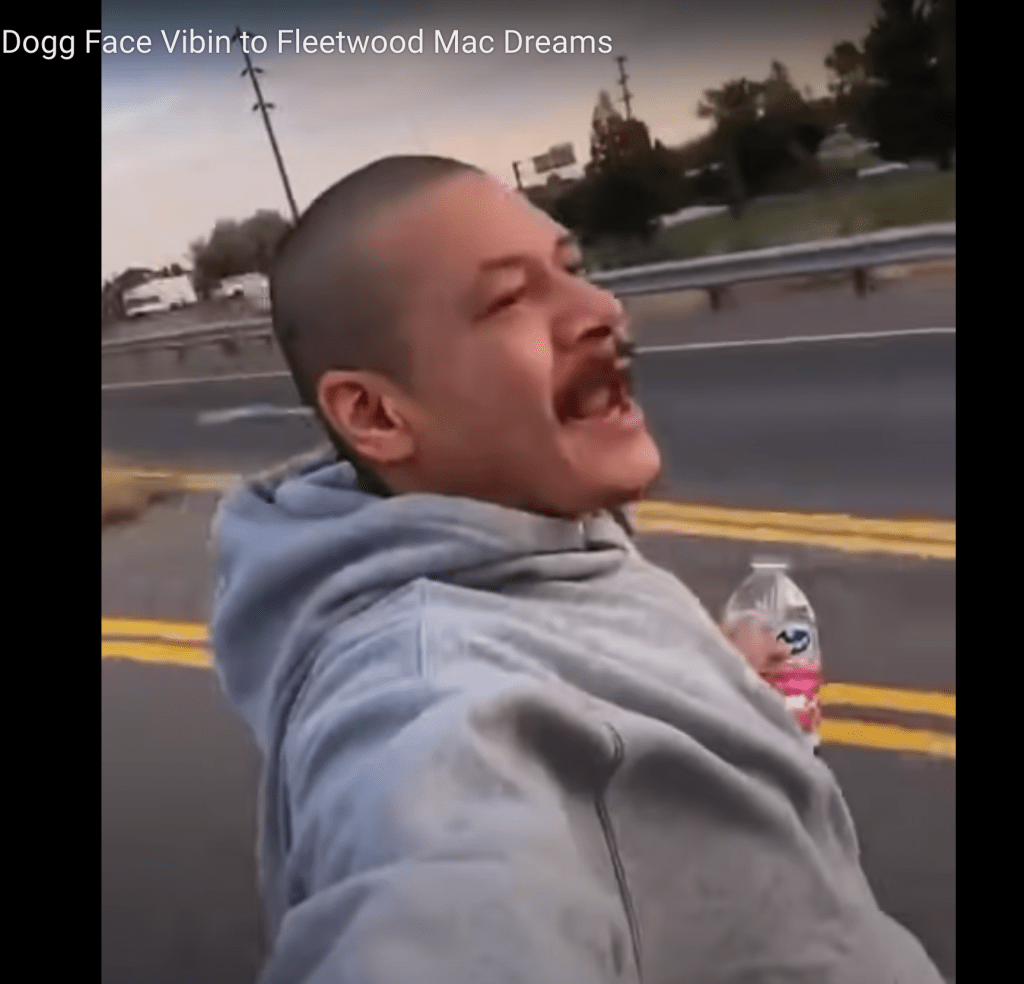

Not only do vibes serve as a prompt for an attempt at articulating experience, they are also invitations to co-presently experience what seems inarticulable. By capturing patterns in media and culture in order to produce a coherent image/sound assemblage, the production of a vibe is predicated upon the ability to draw upon large swathes of visual, aural, and environmental data. Take for example, the story of Nathan Apodaca, known by his TikTok handle as: 420doggface208. After posting a video of himself listening to Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams” while drinking cranberry juice and riding a longboard, Apodaca went viral, amassing something like 30 million views in mere hours. This subsequently sparked a trend in which TikTok users posted videos of themselves doing the same thing, using “Dreams” as the sound. According to Billboard, this sparked the largest ever streaming week for Fleetwood Mac’s 1977 hit with over 8.47 million streams. Of his overnight success, Apodaca says, “it’s just a video that everyone felt a vibe with.” To invoke a vibe is thus to make a particular atmosphere more comprehensible to someone else, producing a resonant effect that draws people together.

As both an extension and tool of culture, vibes are produced by and imbricated within broader social, political, and economic matrices. Recorded music has always been confined—for better and worse—to the technologies, formats, and mediums through which it has been produced for commercial sale. On a platform like TikTok, wherein the emphasis is on potentially quirky microsections of songs, artists are invited to key their work towards those parameters in order to maximize commercial success. Nowadays, pop songs are produced with an eye towards their ability to go viral, be remixed, re-released with a feature verse, meme’d, or included in a mashup. As such, when an artist ‘blows up’ on TikTok, it does not necessarily mean that the sound of the song is good (whatever that might mean). Rather, it might instead be the case that a hybrid assemblage of sound, performance, narrative, and image has coalesced successfully into an atmosphere or texture – that we recognize as a/the vibe – something that not only resonates but also sells well. As TikTok’s success continues to proliferate, the app is continually being developed in ways that make it an indispensable part of the popular music industry’s ecosystem. Whether by exposing users to new musical content through the circulation of sounds, or capitalizing upon the speed at which the app moves to brand a song a ‘single’ before it’s even released, TikTok leverages the vibe to get users to listen differently.

@jimmyfallon This one’s for you @420doggface208 #cranberrydreams#doggface208#dogfacechallenge♬ original sound – Jimmy Fallon

We might indeed consider vibes to be conceptual, affective algorithms created in the interstice between lived experience and new media. “Meet Me At Our Spot,” the track through which I’ve framed this article, is full of allusions to youth culture: drunk texts, anxiety over aging, and late-night drives on the 405. It is buoyed by a propulsive bass line that thumps with a restless energy and evokes a mood of escapism. Willow Smith’s intriguing timbre and the pleasing harmonies she achieves with Tyler Cole invite listeners to ride shotgun. For the two minutes and twenty-two seconds of the song, we are immersed within their world. In the final measures the pop of the snare recedes into the background and Tyler’s voice fades away. The vibe of the track – both sonically and thematically – is predicated on the experience of a few, fleeting moments. Willow leaves us with a final provocation, one that resonates with popular music’s current mode: “Caught a vibe, baby are you coming for the ride?”

—

Featured Image: Screencap of Nathan Apodaca’s viral TikTok post, courtesy of SO! eds.

—

Jay Jolles is a PhD candidate in American Studies at the College of William and Mary currently at work on a dissertation tentatively titled “Man, Music, and Machine: Audio Culture in a/the Digital Age.” He is an interdisciplinary scholar with interests in a wide range of fields including 20th and 21st century literature and culture, critical theory, comparative media studies, and musicology. Jay’s scholarly work has appeared in or is forthcoming from The Los Angeles Review of Books, U.S. Studies Online, and Comparative American Studies. His essays can be found in Per Contra, The Atticus Review, and Pidgeonholes, among others. Prior to his time at William and Mary, he was an adjunct professor of English at Drexel University and Rutgers University-Camden.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Listen to yourself!: Spotify, Ancestry DNA, and the Fortunes of Race Science in the Twenty-First Century”–Alexander W. Cohen

Evoking the Object: Physicality in the Digital Age of Music–-Primus Luta

“Music is not Bread: A Comment on the Economics of Podcasting”-Andreas Duus Pape

“Pushing Record: Labors of Love, and the iTunes Playlist”–Aaron Trammell

Critical bandwidths: hearing #metoo and the construction of a listening public on the web–Milena Droumeva

TiK ToK: Post-Crash Party Pop, Compulsory Presentism and the 2008 Financial Collapse—Dan DiPiero (The other “TikTok”! The people need to know!)

Recent Comments