Toward a Practical Language for Live Electronic Performance

Amongst friends I’ve been known to say, “electronic music is the new jazz.” They are friends, so they smile, scoff at the notion and then indulge me in the Socratic exercise I am begging for. They usually win. The onus after all is on me to prove electronic music worthy of such an accolade. I definitely hold my own; often getting them to acknowledge that there is potential, but it usually takes a die hard electronic fan to accept my claim. Admittedly the weakest link in my argument has been live performance. I can talk about redefinitions of structure, freedom of forms and timbral infinity for days, but measuring a laptop performance up to a Miles Davis set (even one of the ones where his back remained to the crowd) is a seemingly impossible hurdle.

Mind you, I come from a jazzist perspective, which means that I consider jazz the pinnacle of western music. My classicist interlocutors will naturally cite the numerous accomplishments of classical composers as being unmatched within jazz. That will bring us to long debates about the merits of Charles Mingus and Duke Ellington as a composers, which leads, for a good many, to a concession on the part of Duke at least, but an inevitable assertion of the general inferiority U.S. composers compared to the European canon. And then I will say “why are we limiting things to composition when jazz goes so much further than the page?” To which I will get the reply: “orchestral performers were of the highest caliber.” Then I will rebut, “well why was Europe so impressed by Sidney Bechet?” But I digress.

Why talk about classical music in a piece on electronic music, you, my current interlocutor, may ask? Well, in placing electronic music in a historical context, its current stage of development keeps pace with the mental cleverness found in classical but applies it to different theoretical principles. The electronic musician’s DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) file amounts to the classical composer’s score; the electronic musician’s DSP (Digital Signal Processor) parallels the classical composer’s orchestra. I could call electronic music “the new classical” and I’d have a few supporters. But. . .taking it to the level of jazz? Electronic music would have to include not only the mental cleverness, but the physical cleverness as well.

Electronic artist using Ableton 5 Live, Image by Flickr user Nofi

Let’s back up for a bit. A couple years back, I did a piece for Create Digital Music on Live Electronic performance. I talked to a diverse group of artists about their processes for live performance, and I wrote it up with some video examples. It ended up being one of the most discussed pieces on CDM that year, with commentary ranging from fascination at the presentation of techniques to dismissal of the videos as drug-addled email inbox management.

This was to be expected, because of the lack of a language for evaluating electronic music. It is impossible to defend an artist who has been called a hack without the language through which to express their proficiency. Using Miles Davis as an example–specifically a show where his back is to the audience–there are fans that could defend his actions by saying the music he produced was nonetheless some of the best live material of his career, citing the solos and band interactions as examples. To the lay person, however, it may just seem rude and unprofessional for Davis to have his back to the audience; as such, it cannot be qualitatively a good performance no matter what. Any discussion of tone and lyrical fluidity often means little to the lay person.

The extent of this disconnect can be even greater with electronic performances. With his back turned to the audience, they can no longer see Miles’ fingers at work, or how he was cycling breath. Even when facing the crowd, an electronic musician whose regimen is largely comprised of pad triggers, knob turns, and other such gestures which simply do not have the same expected sonic correspondence as, for example, blowing and fingering do to the sound of a trumpet. Also, it is well known that the sound the trumpet produces cannot be made without human action. With electronic music however, particularly with laptop performances, audiences know that the instrument (laptop) is capable of playing music without human aid other than telling it to play. The “checking their email” sentiment is a challenge to the notion that what one is seeing in a live electronic performance is indeed an “actual performance.”

In the time since writing the CDM piece, I’ve seen well over a hundred live sets, listened to days worth of live recordings, spoken in-depth with countless artists about their choices on stage, and gauged fan reactions many times over: from mind-blowing performances in barns to glorified electronic karaoke in sold-out venues, tempo locked beat matching to eight channel cassette tape loops, ten thousand dollar hardware to circuit bent baby toys. After all of that, I still don’t know that I can win the jazz vs. electronic music debate, but I will at least try.

*****

A while back, I was paging through the December 2011 edition of The Wire when I came upon a review of a Flying Lotus performance, the conclusion of which stood out:

On record, the music has the unruly liquidity of dream logic wandering from astral pathways down alphabet street, returning via back alleys on its own whims. Maybe the listening mind, presented with pretty straight analogues of those tracks, rebels, expecting something more mercurial, more improvised. The atmosphere in the venue reflected this upper-downer tension and constraint: the crowd noise was positive, but crowd movement was minimal – a strange sight in the midst of FlyLo’s headier jams. When the hall emptied there was a grumbling undercurrent as the tide of humanity was spilling slowly down the Roundhouse steps, whispers of it must have reached the upper levels. One casualty high above leaned over to berate them: “You don’t know, even understand, what you just FELT.” Sadly though, he didn’t stick around to enlighten anyone.

It should be noted that there are positive reviews of the show, and while not necessarily the best gauge, the videos from the event may seem to tell a different story.

What stood out for me from the review however, was that in trying to write about what the writer felt was a less than stellar performance, there was only one critique which could directly be attributed to the music, which was to say that Flying Lotus performed “straight analogues” of his tracks. Beyond that, the writer was left describing the feelings from the audience.

Feelings are tricky things. We all have them and they are the fundamental point of connection we seek when experiencing music. The message conveyed through the medium of music is meant to be an emotional one. But measuring those emotions is a task which cannot escape subjectivity. In a case like this when one writer is attempting to speak for the feelings of the whole audience, it becomes really tricky. Sure the writer may consider their analysis to have been objective, but it was still based on their perception of the audience, not the audience’s perception. Even more, this gauging of the audience dynamic does not tell us how the actual music performance was regardless of the varied perspectives from within the audience. I contend that this gap occurs because the language for discussing electronic performance has not yet been established.

Around the time I read The Wire review I was also reading Adam Harper’s Infinite Music, which offers variability as a primary factor of analysis in music. Instead of building on traditional music theory, Harper takes cues from those on the fringes of western music. He builds a concept of ‘music space’ by expanding John Cage’s “sound space,” the limits of which are ear determined. Furthermore, Harper’s non-musical variables and how they play into creating individually unique musical events, strengthens Christopher Small’s notion of musicking as a verb. In this way, Harper creates a fluid language for discussing music which might prove practical for these purposes.

It is helpful to use one of the central concepts of Harper’s music space, musical objects, as a means of distinguishing electronic performance.

Systems of variables constitute musical objects – Adam Harper

Going back to Miles Davis, his instrument is a monophonic musical object with a limited pitch and dynamic range in the upper register of the brass timbre. His musical talent is evaluated based on how he is able to work within those limitations to create variable experiences. His band represents another musical object comprised of the individual players as musical objects as well. The venue in which they are playing is a musical object, as is the audience and Davis’ decision to perform with his back to it. It is the coming together of all of these musical objects that creates the musical event (an alternate event includes the musical object which recorded the performance, and the complete setting of the listener as an individual musical objects upon playing the live recording). In a musical event comprised of these musical objects – Davis performing live in front of an audience with his back turned so he can face the band–it is possible to imagine a similar reaction to the above commentary about Flying Lotus, including a guy berating the audience for not making the connection.

Miles Davis @ Montreux, 8.7.1984 Image by Flickr user Christophe Losberger

In this Davis example however, we could listen to the audio to determine whether or not it was a “good” performance by analyzing the musical objects which can be observed in the recording (note: this would be technical analysis of the performance, not the event or its reception). Does Davis’s tone falter? How strong are the solos? Is he staying in the pocket with the rest of the band? Evaluation of these variables would be a testament to his proficiency which could be compared to other performances to determine if it measures up.

Flying Lotus’s set however is a bit different. Yes, we could listen back to the audio (or watch the video) and determine if indeed it measures up to other sets he has performed, but unlike with Davis, we cannot translate what we hear directly to his agency. When we hear the trumpet on the Davis recording we know that the sound is caused by him physically blowing into his instrument. When we hear a bass in a Flying Lotus set, there isn’t necessarily a physical act associated with the creation of the sound. With all of the visual cues removed in the Davis example, we can still speak about the performance aspect of the music; the same is not necessarily so about an electronic set, even with visual cues. In many electronic sets, it is only when something goes wrong that actual agency in the music being performed can be attributed.

Flying Lotus,@ SonarDome, Sonar 2012, Image by Flickr user Boolker

Where the advent of the laptop and DSP advances for music have expanded creative possibilities, they only shroud what the performers using them are actually doing in more mystery. It’s an esoteric language, or perhaps languages, as ultimately each artist’s live rig configuration amounts to different musical objects, across which there may not be compatibilities.

However, in certain musical circles there are common musical objects. Perhaps the most common musical object for performance in electronic music right now is Ableton Live, which results in common component musical objects across performances by different artists. Further, an Ableton Live set can sound just like a Roland 404 set, which can sound just like a DJ set with a Kaoss pad, all of which can sound identical to a set not performed live but produced in the studio (or bedroom as the case may be) for a podcast. The reason for this is that much of the music is already fixed. What changes is the sequencing of these fixed pieces of music over time, their transitions and the variety of effects employed. The goal for these types of sets is a continuous flow of pre-arranged music, which parallels that of a DJ set.

In the past few years, the line between a live electronic set and a DJ set has been blurred extensively. Fans have become fairly critical of artists, to the point that it has become standard practice for promoters to list whether performances will be live or a DJ set. Even on the DJ end of the spectrum there’s a lot of questions, as artists have been called out for their DJ set being an iPod playlist. To qualify as a live set however, an artist must be doing more than just playing songs. How much more is debatable, but should it be?

Flying Lotus – Sónar 2012 – Jueves 14/05/2012, Image by Flickr user scannerfm

Nobody in their right mind would call Miles Davis a hack. Even if they didn’t like specific performances, few would question his proficiency with the instrument. The reason for this is that his talent rises above the standard performance, beneath which someone could be qualified as a hack. If a trumpet player spent a whole night performing only shrill notes of a C major chord around middle C, without properly qualifying that their performance would be so constrained as a stylistic choice, one might consider calling that artist out as a hack (I apologize in advance to the serious musician that fits in this description).

The rationale behind this assessment is based on knowing the potential variability of the instrument and realizing that the performer is not exploring any of that variability. Perhaps there could be other layers of variability (e.g. an effects chain) added to the trumpet to make it interesting musically, but it can be objectively said that they don’t measure up to a standard quality of a trumpet player. If we say that the trumpet has an extensive dynamic range, a tonality which can go from smooth to harsh and a pitch range of just over three octaves, we can see how the player in our example is exhibiting quite a low proficiency.

This goes across all styles of trumpet playing. Were a style to impose limitations on a player, it could be said that the style did not allow for the full expression of proficiency on the instrument. A player within that style could be considered proficient in that context, but would require a broader performance to be analyzed for general proficiency. So the player in our example could be a master of “Shrill C” trumpet, but in order to compare with a Miles Davis they would have to perform out of style. Conversely, Miles Davis may be one of the world’s greatest trumpet players, but possibly the worst “Shrill C” trumpet player ever.

From this we can see that the language of variability provides a unique way to objectively speak on the performance of musical objects, while fully taking into account the way styles can play into performance. Using this language we open the world of electronic performance up for analysis and comparison.

—

This is part one of a three part series. In my next installment, I will use some of the language here to analyze the instruments and techniques used in electronic performance today. Once we have a fluid language for describing what is being used, I believe we will be better equipped to speak about what happens on stage.

—

Featured Image by Flickr User Scanner FM, Flying Lotus – Sónar 2012 – Jueves 14/05/2012

—

Primus Luta is a husband and father of three. He is a writer and an artist exploring the intersection of technology and art, and their philosophical implications. He is a regular guest contributor to the Create Digital Music website, and maintains his own AvantUrb site. Luta is a regular presenter for the Rhythm Incursions Podcast series with his monthly showRIPL. As an artist, he is a founding member of the live electronic music collectiveConcrète Sound System, which spun off into a record label for the exploratory realms of sound in 2012.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Experiments in Agent-based Sonic Composition–Andreas Pape

Evoking the Object: Physicality in the Digital Age of Music–-Primus Luta

Sound as Art as Anti-environment–Steven Hammer

Evoking the Object: Physicality in the Digital Age of Music

In our current relationship with technology, we bring our bodies, but our minds rule–Linda Stone, “Conscious Computing”

I begin with an epigraph from Linda Stone, who coined the phrase ‘continuous partial attention’ to describe our mental state in the digital age. The passive cousin of multi-tasking, continuous partial attention is a reaction to our constantly connected lifestyles in which everything is happening right now and where value is increasingly equated with our ability to digest it all. Almost everything we do has the potential to be interrupted, be it by an email, a text or a tweet; often we will give only partial attention to any one thing in anticipation of the next thing that will require our attention. In this internal fight for mental attention, listening to music has been seriously impacted.

The digital era has seen more music releases than ever before. Unfortunately, the massive influx of quantity is by no means a measure of how we are engaging with said music. iPhones and similar devices, for which music players have become mere features, enable listening to become a thing of partial attention. From allowing the shuffle or random modes to choose music selections for you, or even streaming music algorithms to calculate things you might like, to listening while playing Angry Birds or reading your Twitter stream, less commitment is made to the act of listening, and as such only a portion of our working memory is committed to the experience. Without working memory actively processing musical information, it is less likely to be stored for the long term, particularly if other information is continuously vying for space and attention.

These days video games sell better than music. Despite being a digital product, games are able to instill memories (even of the music) into one’s consciousness, because the game interface allows our sensory memories to work together in an active manner with the medium. Iconic memory stores visual cues from the game, echoic memory takes the audible cues from the game and the haptic memory is engaged in controlling game play. There is only so much more which can be done while playing a video game. If something were to interrupt game play, the game would be paused to address the new information rather than giving it partial attention. This is quite different from music which plays a background role in so much of our lives even when we are actively putting music on we tend to only engage it with partial attention.

When I began thinking about turning Concrète Sound System into a record label, one of my main goals was to create works that could engage the audience in active musical experiences that could create long term memories. I felt that as important as the music would be, it would take something material to create these memories, a physical product more evocative of earlier moments in recording history than the CD, its most recent gasp. I wondered if, by creatively evoking the physical object, the listener could be engaged in an active manner that would enable the memory of music and its power to persist through the everyday waves of digital noise.

The first mass duplicated audio medium was the Gold Moulded Edison Cylinder at the turn of the twentieth century. Imagine two cylinder copies of one of these recording today, as musical objects. Each of them would have over a hundred years of physical history. From the wear of the cases to the condition of the wax based on the temperature in which they were stored, each of these cylinders would be unique musical objects, with completely different histories, despite having the same origin. It is reasonable to assume that if the cylinders were played today on the same playback device, despite the fact that the compositions and performances are exactly the same, the differences between the recordings would be audible.

Wax Cylinders in the Library of Congress preservation Lab, Image by Flickr User Photo Phiend

Even without a century of history, there would likely be audible differences between the cylinders. If one cylinder was the first copy made, and another the 150th –master cylinders of Gold Moulded Edison Cylinders could only produce 150 copies reliably–the physical wear in the process of reproduction would leave its own imprint, making each of those copies distinct musical objects. In the analog world, as the technology improved the differences between copies decreased substantially. Cassettes were manufactured in batches of ten to hundreds of thousands without audible differences. But even in circulations so high, over time each of those analog copies took on their own identity and collected their own memories.

The listener as an active agent contributed to the development of these unique musical objects. After a purchase, any number of variables played into the ritual of the first experience of the music. Was there a way to listen upon walking out of the store? Were there liner notes or lyric sheets inside? Would you read those prior to listening or as you listen? Where would you listen? Through headphones? The listening chair in front of the hi-fi stereo? Or on the boombox with some friends? All of these possibilities shaped memories as musical objects that defined the music consumption culture of the past.

For example, I bought the debut 2Pac album 2Pacalypse Now on cassette the day it was released. I loved the album so much I kept it in regular rotation in my Walkman for months until finally the tape popped. Rather than go out and buy a new copy I decided to perform a surgery. It was in a screwless reel case which meant I couldn’t just open it up to retrieve the ends of the tape trapped inside, but rather had to crack the reel case open and transplant the reels into a new body. So, my copy of the 2Pacalypse Now cassette is now inside of a clear reel holder with no visual markings. It also has a piece of tape that was used to splice it back together, which makes an audible warp when played back. I can pretty much be sure that there is no other copy of 2Pacalypse which sounds exactly like mine. While this probably detracts from the resale value of the cassette (not that I’d sell it), it is imbued with a personal history that is priceless.

For example, I bought the debut 2Pac album 2Pacalypse Now on cassette the day it was released. I loved the album so much I kept it in regular rotation in my Walkman for months until finally the tape popped. Rather than go out and buy a new copy I decided to perform a surgery. It was in a screwless reel case which meant I couldn’t just open it up to retrieve the ends of the tape trapped inside, but rather had to crack the reel case open and transplant the reels into a new body. So, my copy of the 2Pacalypse Now cassette is now inside of a clear reel holder with no visual markings. It also has a piece of tape that was used to splice it back together, which makes an audible warp when played back. I can pretty much be sure that there is no other copy of 2Pacalypse which sounds exactly like mine. While this probably detracts from the resale value of the cassette (not that I’d sell it), it is imbued with a personal history that is priceless.

Cassettes, in particular, played a significant role in the attachment of physical memories to music beyond the recordings they held. They gave birth to the mixtape. The taper community was born from personal tape recorders that allowed concert-goers to record performances they attended, and, prior to the rise of peer to peer sharing online, these communities were trading tapes internationally via regular postal mail. European jazz and rock concerts were finding their way back to the states and South Bronx hip-hop performances were traveling with the military in Asia. All of these instances required a physical commitment with which came memories that inherently became their own musical objects.

Needless to say the nature of musical exchange has changed with the rise of the digital age of music. This is not to say that memories as musical objects have gone away, but they are being taken for granted as the objects lose their physicality. I remember going to The Wiz on 96th Street with $10 to spend on music. I spent at least ten minutes trying to decide between Sid and B-Tonn and Arabian Prince. I ended up with Arabian Prince and have regretted it since I got home and listened that day, as I never found Sid and B-Tonn for sale again. Today I could download both in the time it took me to walk to the train station. After skimming through the first few songs of Arabian Prince I could decide it was not for me and drag drop it in the trash where the memory of it would disappear with the files. No matter how I felt about the music then, the memory of it is a permanent fixture in my mind because of the physical actions it took to listen.

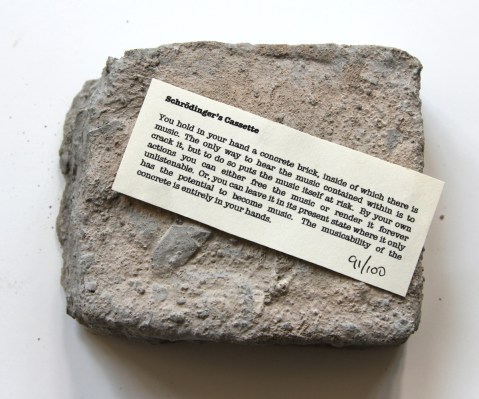

The first release for Concrète Sound System, Schrödinger’s Cassette, tackled this issue head on by presenting the audience with its own paradox, an update of physicist Erwin Schrödinger’s famous Thought Experiment, where the ultimate fate of the cassette inside is left up to the individual. Schrödinger’s Cassette sought to take listeners out of digital modes of consumption by using an analog medium to evoke the physical. The cassette release trend has been growing over the last few years, almost in parallel to the rise of the digital music and speaking to the need to separate music from our digital lives and to a desire to work harder for it. At the minimum, listening to a cassette requires having a cassette player, and acquiring one these days takes commitment. Unlike digital media, listeners cannot instantly skip a song on a cassette or put a favorite on repeat. It takes physical manipulation of the medium to move through its songs and doing so is a time investment. All these limitations make the cassette a medium that is best for linear listening, from beginning to end (unless you physically cut, rearrange, and splice it yourself).

Schrödinger’s Cassette, Image Courtesy of The Wire

Schrödinger’s Cassette took the required commitment a step further by encasing the cassette itself in industrial grade concrete. This required the user to actively crack the concrete (or the french concrète meaning ‘real’, from which the label derives its name) in order to listen to the music. The paradox is that, depending on the listener’s method for cracking, harm could be done to the cassette that might render it ‘unlistenable’. Upon receiving one of these pieces, the listener holds in their hands a musical object which they must physically act upon in order to create an unrepeatable musical event. Schrödinger’s Cassette has a look, a sound (if shaken you can hear the cassette reels), a feel, a smell, and a taste as well (though I wouldn’t advise it). All of the senses can be actively focused on the object and, as such, the whole of one’s working memory is engaged in the discernment of the object’s musical contents.

The Wire breaks open Schrödinger’s Cassette courtesy of their Twitterstream

For many, Schrödinger’s Cassette was taken as a work of art and left uncracked. The Wire magazine successfully cracked one edition open, revealing a portion of the musical contents on their regular radio program. For those that decided not to crack it, digital versions were made available so that they could listen, though this option was only made available after the listener spent some time with their physical object. In this way, the music from the project, a compilation called Between the Cracks, was directly connected to physical memories spurred by a material presence.

Triggering active memory during the consumption of music through physical objects need not be this complex. Old medium such as vinyl and cassette releases inherently have the physical properties required without the concrete or much else. Perhaps for this reason they show new signs of life despite the rise of digital. No matter how much our reality is augmented by our digital lives, we still inhabit those bodies that we bring with us, and, as far as the memories those bodies carry with them go, physicality rules.

—

Featured Image: Wax Cylinders in the Library of Congress, Image by Flickr User Photo Phiend

—

Primus Luta is a husband and father of three. He is a writer and an artist exploring the intersection of technology and art, and their philosophical implications. He is a regular guest contributor to theCreate Digital Music website, and maintains his own AvantUrb site. Luta is a regular presenter for the Rhythm Incursions Podcast series with his monthly showRIPL. As an artist, he is a founding member of the live electronic music collectiveConcrète Sound System, which spun off into a record label for the exploratory realms of sound in 2012.

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- SO! Reads: Alexis McGee’s From Blues To Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics

- SO! Reads: Justin Eckstein’s Sound Tactics: Auditory Power in Political Protests

- Impaulsive: Bro-casting Trump, Part I

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments