Erratic Furnaces of Infrasound: Volcano Acoustics

Welcome back to Hearing the UnHeard, Sounding Out‘s series on how the unheard world affects us, which started out with my post on hearing large and small, continued with a piece by China Blue on the sounds of catastrophic impacts, and now continues with the deep sounds of the Earth itself by Earth Scientist Milton Garcés.

Welcome back to Hearing the UnHeard, Sounding Out‘s series on how the unheard world affects us, which started out with my post on hearing large and small, continued with a piece by China Blue on the sounds of catastrophic impacts, and now continues with the deep sounds of the Earth itself by Earth Scientist Milton Garcés.

Faculty member at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and founder of the Earth Infrasound Laboratory in Kona, Hawaii, Milton Garces is an explorer of the infrasonic, sounds so low that they circumvent our ears but can be felt resonating through our bodies as they do through the Earth. Using global networks of specialized detectors, he explores the deepest sounds of our world from the depths of volcanic eruptions to the powerful forces driving tsunamis, to the trails left by meteors through our upper atmosphere. And while the raw power behind such events is overwhelming to those caught in them, his recordings let us appreciate the sense of awe felt by those who dare to immerse themselves.

In this installment of Hearing the UnHeard, Garcés takes us on an acoustic exploration of volcanoes, transforming what would seem a vision of the margins of hell to a near-poetic immersion within our planet.

– Guest Editor Seth Horowitz

—

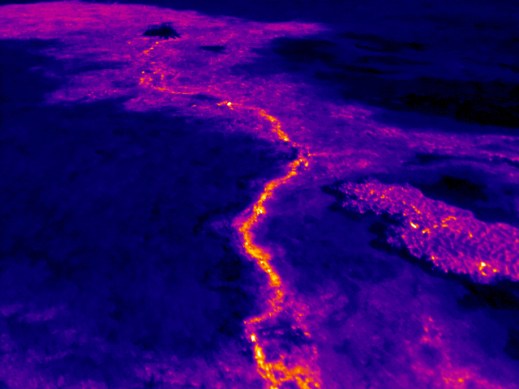

The sun rose over the desolate lava landscape, a study of red on black. The night had been rich in aural diversity: pops, jetting, small earthquakes, all intimately felt as we camped just a mile away from the Pu’u O’o crater complex and lava tube system of Hawaii’s Kilauea Volcano.

The sound records and infrared images captured over the night revealed a new feature downslope of the main crater. We donned our gas masks, climbed the mountain, and confirmed that indeed a new small vent had grown atop the lava tube, and was radiating throbbing bass sounds. We named our acoustic discovery the Uber vent. But, as most things volcanic, our find was transitory – the vent was eventually molten and recycled into the continuously changing landscape, as ephemeral as the sound that led us there in the first place.

Volcanoes are exceedingly expressive mountains. When quiescent they are pretty and fertile, often coyly cloud-shrouded, sometimes snowcapped. When stirring, they glow, swell and tremble, strongly-scented, exciting, unnerving. And in their full fury, they are a menacing incandescent spectacle. Excess gas pressure in the magma drives all eruptive activity, but that activity varies. Kilauea volcano in Hawaii has primordial, fluid magmas that degass well, so violent explosive activity is not as prominent as in volcanoes that have more evolved, viscous material.

Well-degassed volcanoes pave their slopes with fresh lava, but they seldom kill in violence. In contrast, the more explosive volcanoes demolish everything around them, including themselves; seppuku by fire. Such massive, disruptive eruptions often produce atmospheric sounds known as infrasounds, an extreme basso profondo that can propagate for thousands of kilometers. Infrasounds are usually inaudible, as they reside below the 20 Hz threshold of human hearing and tonality. However, when intense enough, we can perceive infrasound as beats or sensations.

Like a large door slamming, the concussion of a volcanic explosion can be startling and terrifying. It immediately compels us to pay attention, and it’s not something one gets used to. The roaring is also disconcerting, especially if one thinks of a volcano as an erratic furnace with homicidal tendencies. But occasionally, amidst the chaos and cacophony, repeatable sound patterns emerge, suggestive of a modicum of order within the complex volcanic system. These reproducible, recognizable patterns permit the identification of early warning signals, and keep us listening.

Each of us now have technology within close reach to capture and distribute Nature’s silent warning signals, be they from volcanoes, tsunamis, meteors, or rogue nations testing nukes. Infrasounds, long hidden under the myth of silence, will be everywhere revealed.

The “Cookie Monster” skylight on the southwest flank of Pu`u `O`o. Photo by J. Kauahikaua 27 September 2002

I first heard these volcanic sounds in the rain forests of Costa Rica. As a graduate student, I was drawn to Arenal Volcano by its infamous reputation as one of the most reliably explosive volcanoes in the Americas. Arenal was cloud-covered and invisible, but its roar was audible and palpable. Here is a tremor (a sustained oscillation of the ground and atmosphere) recorded at Arenal Volcano in Costa Rica with a 1 Hz fundamental and its overtones:

.

In that first visit to Arenal, I tried to reconstruct in my minds’ eye what was going on at the vent from the diverse sounds emitted behind the cloud curtain. I thought I could blindly recognize rockfalls, blasts, pulsations, and ground vibrations, until the day the curtain lifted and I could confirm my aural reconstruction closely matched the visual scene. I had imagined a flashing arc from the shock wave as it compressed the steam plume, and by patient and careful observation I could see it, a rapid shimmer slashing through the vapor. The sound of rockfalls matched large glowing boulders bouncing down the volcano’s slope. But there were also some surprises. Some visible eruptions were slow, so I could not hear them above the ambient noise. By comparing my notes to the infrasound records I realized these eruption had left their deep acoustic mark, hidden in plain sight just below aural silence.

I then realized one could chronicle an eruption through its sounds, and recognize different types of activity that could be used for early warning of hazardous eruptions even under poor visibility. At the time, I had only thought of the impact and potential hazard mitigation value to nearby communities. This was in 1992, when there were only a handful of people on Earth who knew or cared about infrasound technology. With the cessation of atmospheric nuclear tests in 1980 and the promise of constant vigilance by satellites, infrasound was deemed redundant and had faded to near obscurity over two decades. Since there was little interest, we had scarce funding, and were easily ignored. The rest of the volcano community considered us a bit eccentric and off the main research streams, but patiently tolerated us. However, discussions with my few colleagues in the US, Italy, France, and Japan were open, spirited, and full of potential. Although we didn’t know it at the time, we were about to live through Gandhi’s quote: “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.”

Fast forward 22 years. A computer revolution took place in the mid-90’s. The global infrasound network of the International Monitoring System (IMS) began construction before the turn of the millennium, in its full 24-bit broadband digital glory. Designed by the United Nations’s Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), the IMS infrasound detects minute pressure variations produced by clandestine nuclear tests at standoff distances of thousands of kilometers. This new, ultra-sensitive global sensor network and its cyberinfrastructure triggered an Infrasound Renaissance and opened new opportunities in the study and operational use of volcano infrasound.

Suddenly endowed with super sensitive high-resolution systems, fast computing, fresh capital, and the glorious purpose of global monitoring for hazardous explosive events, our community rapidly grew and reconstructed fundamental paradigms early in the century. The mid-naughts brought regional acoustic monitoring networks in the US, Europe, Southeast Asia, and South America, and helped validate infrasound as a robust monitoring technology for natural and man-made hazards. By 2010, infrasound was part of the accepted volcano monitoring toolkit. Today, large portions of the IMS infrasound network data, once exclusive, are publicly available (see links at the bottom), and the international infrasound community has grown to the hundreds, with rapid evolution as new generations of scientists joins in.

In order to capture infrasound, a microphone with a low frequency response or a barometer with a high frequency response are needed. The sensor data then needs to be digitized for subsequent analysis. In the pre-millenium era, you’d drop a few thousand dollars to get a single, basic data acquisition system. But, in the very near future, there’ll be an app for that. Once the sound is sampled, it looks much like your typical sound track, except you can’t hear it. A single sensor record is of limited use because it does not have enough information to unambiguously determine the arrival direction of a signal. So we use arrays and networks of sensors, using the time of flight of sound from one sensor to another to recognize the direction and speed of arrival of a signal. Once we associate a signal type to an event, we can start characterizing its signature.

Consider Kilauea Volcano. Although we think of it as one volcano, it actually consists of various crater complexes with a number of sounds. Here is the sound of a collapsing structure

As you might imagine, it is very hard to classify volcanic sounds. They are diverse, and often superposed on other competing sounds (often from wind or the ocean). As with human voices, each vent, volcano, and eruption type can have its own signature. Identifying transportable scaling relationships as well as constructing a clear notation and taxonomy for event identification and characterization remains one of the field’s greatest challenges. A 15-year collection of volcanic signals can be perused here, but here are a few selected examples to illustrate the problem.

First, the only complete acoustic record of the birth of Halemaumau’s vent at Kilauea, 19 March 2008:

.

Here is a bench collapse of lava near the shoreline, which usually leads to explosions as hot lava comes in contact with the ocean:

.

.

Here is one of my favorites, from Tungurahua Volcano, Ecuador, recorded by an array near the town of Riobamba 40 km away. Although not as violent as the eruptive activity that followed it later that year, this sped-up record shows the high degree of variability of eruption sounds:

.

The infrasound community has had an easier time when it comes to the biggest and meanest eruptions, the kind that can inject ash to cruising altitudes and bring down aircraft. Our Acoustic Surveillance for Hazardous Studies (ASHE) in Ecuador identified the acoustic signature of these type of eruptions. Here is one from Tungurahua:

.

Our data center crew was at work when such a signal scrolled through the monitoring screens, arriving first at Riobamba, then at our station near the Colombian border. It was large in amplitude and just kept on going, with super heavy bass – and very recognizable. Such signals resemble jet noise — if a jet was designed by giants with stone tools. These sustained hazardous eruptions radiate infrasound below 0.02 Hz (50 second periods), so deep in pitch that they can propagate for thousands of kilometers to permit robust acoustic detection and early warning of hazardous eruptions.

In collaborations with our colleagues at the Earth Observatory of Singapore (EOS) and the Republic of Palau, infrasound scientists will be turning our attention to early detection of hazardous volcanic eruptions in Southeast Asia. One of the primary obstacles to technology evolution in infrasound has been the exorbitant cost of infrasound sensors and data acquisition systems, sometimes compounded by export restrictions. However, as everyday objects are increasingly vested with sentience under the Internet of Things, this technological barrier is rapidly collapsing. Instead, the questions of the decade are how to receive, organize, and distribute the wealth of information under our perception of sound so as to construct a better informed and safer world.

IRIS Links

http://www.iris.edu/spud/infrasoundevent

http://www.iris.edu/bud_stuff/dmc/bud_monitor.ALL.html, search for IM and UH networks, infrasound channel name BDF

—

Milton Garcés is an Earth Scientist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and the founder of the Infrasound Laboratory in Kona. He explores deep atmospheric sounds, or infrasounds, which are inaudible but may be palpable. Milton taps into a global sensor network that captures signals from intense volcanic eruptions, meteors, and tsunamis. His studies underscore our global connectedness and enhance our situational awareness of Earth’s dynamics. You are invited to follow him on Twitter @iSoundHunter for updates on things Infrasonic and to get the latest news on the Infrasound App.

—

Featured image: surface flows as seen by thermal cameras at Pu’u O’o crater, June 27th, 2014. Image: USGS

—

REWIND! If you liked this post, check out …

SO! Amplifies: Ian Rawes and the London Sound Survey — Ian Rawes

Sounding Out Podcast #14: Interview with Meme Librarian Amanda Brennan — Aaron Trammell

Catastrophic Listening — China Blue

Toward A Civically Engaged Sound Studies, or ReSounding Binghamton

I want to enable my students to mobilize sound studies not just as an analytic filter to help them understand the world, but as a method enabling more meaningful engagement with it. This post, an abbreviated version of the paper I recently gave at the Invisible Places, Sounding Cities Conference in Viseu, Portugal on July 18, 2014, explores my pedagogical efforts to move my sound studies work from theory to methodology to praxis in the classroom and in my larger community. In particular, I am working to intervene in the production of social difference via listening and the process by which differential listening practices create fractured and/or parallel experiences of allegedly shared urban spaces.

I want to enable my students to mobilize sound studies not just as an analytic filter to help them understand the world, but as a method enabling more meaningful engagement with it. This post, an abbreviated version of the paper I recently gave at the Invisible Places, Sounding Cities Conference in Viseu, Portugal on July 18, 2014, explores my pedagogical efforts to move my sound studies work from theory to methodology to praxis in the classroom and in my larger community. In particular, I am working to intervene in the production of social difference via listening and the process by which differential listening practices create fractured and/or parallel experiences of allegedly shared urban spaces.

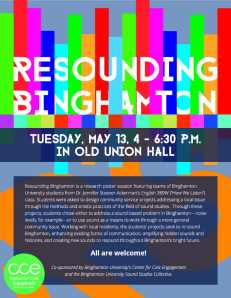

Click for flyer, designed by Peter Liu

Inspired by ongoing efforts such as ReBold Binghamton–the visual arts group alluded to by my assignment’s title– Blueprint Binghamton, and the Binghamton Neighborhood Project, I wanted to articulate sound studies methods with long-term community engagement interventions. I decided to task the upper-level undergraduate students in my Spring 2014 “How We Listen” course with designing community engagement projects that identified and addressed an issue in Binghamton, the de-industrialized town in upstate New York housing our university. My students’ proposals ranged from rain-activated sound art, to historical sound walks that layered archival sounds with current perceptions, and a “noise month” sound-collection and remix project designed to challenge entrenched attitudes. They then presented the projects via a public poster session open to faculty members, administrators, community representatives, and peers.

Working with local residents and using asset-based theories of civic engagement, the students’ projects sought to re-sound Binghamton, enhancing existing forms of communication, amplifying hidden sounds and histories, and creating new sounds to resound throughout Binghamton’s future. While the students initially set out to “fix” Binghamton—bringing year-round residents into the world as their largely 18-21 selves heard it—the majority opened their ears to alternative understandings that left them questioning the exclusivity of their own listening practices. Students realized that while they may have been inhabiting Binghamton for the past few years, they hadn’t been perceptually living in the same town as year-round residents, and, conversely, that the locals’ tendencies to hear students as privileged nuisances had historical and structural roots.

The historical, theoretical, and methodological groundwork that scholars of sound have laid in recent decades toward heightened social and political understandings of sound—fantastic in volume, quality, AND reach—have equipped sound studies scholars with powerful critical tools with which to build a more directly, civically engaged sound studies, one as much interested in intervention and prevention as continued reclamation and recovery. Scholar-artists such as Linda O’Keeffe have begun to fuse audio artistic praxis with the more social science-oriented field of urban studies. O’Keeffe’s community project, highlighted in “(Sound)Walking Through Smithfield Square in Dublin,” set out to solve an audio- spatial problem at the very heart of the city: why did the city’s efforts to “rehabilitate” the landmark Smithfield Square—which had been a public market for hundreds of years—bring about its demise as a thriving public space rather than its rejuvenation? Equipping local students with recorders, O’Keeffe documented the students’ understanding of the space as “silent,” even though it was far from absent of sound. She noted local teenagers felt repelled by the newly wide-open square; the reverberation of their sounds as they grouped together to chat made them feel uncomfortable and surveilled—so it remained an isolating space of egress rather than a gathering place.

The Smithfield square in 2009, Image by Linda O’Keeffe

Importantly, O’Keeffe’s conclusion moved beyond self-awareness to political praxis; she presented her students’ self-documentation to Dublin city planners, intervening in Smithfield’s projected future and attempting to prevent similar destruction of other thriving city soundscapes unaligned with middle-class sensory orientations. O’Keeffe’s work sparked me to think of listening’s potential as advocacy and agency, as well as the increasing importance of reaching beyond the identification of diverse listening habits toward teaching people to understand the partiality and specificity of their sonic experience in combination with the impact listening—and the power dynamics it is enmeshed in—has on the lives, moods, and experiences of themselves and others. Listening habits, assumptions, and interpretations do not just shape individual thoughts and feelings, but also one’s spatial experience and sense of belonging to (or exclusion from) larger communities, both actual and imagined. Learning to understand one’s auditory experience and communicate it in relation to other people enables new forms of civic engagement that challenge oppression at the micro-level of the senses and seeks equitable experiences of shared space to counter the isolating exclusion compelled by many urban soundscapes.

Corner of Front and Main Street, Binghamton, NY, Image by Flickr User Don Barrett

O’Keeffe’s project also made me rethink how space-sound is shaped through social issues such as class inequity, particularly in my community of Binghamton, a small town of approximately 54,000 currently facing profound economic challenges. The end of the Cold War devastated Binghamton’s economy—then primarily based in defense—and the economic downturn of the early-1990s provided a knock-out punch, severely impacting the region in ways it has yet to recover from: the behemoth local IBM relocated to North Carolina, manufacturing jobs permanently decreased by 64%, and the population shrank almost by half. Recent climate-change induced disasters have also left their mark; massive floods in 2005 and 2011—on a geographic footprint historically flooding only 200-500 years—displaced thousands of low-income residents, destroyed many businesses, and collectively caused close to 2 billion dollars in damage. The global recession of 2008 left over 30% of Binghamton’s residents below the poverty line, including 40% of all children under 18.

Library Tower, Binghamton University, Image by Flickr User johnwilliamsphd

The campus, 12,000 undergraduate students strong, often seems remote from the city I just described. Only 6% of BU students are drawn from its surrouding Broome County. The vast majority (60%) of BU’s students hail from the New York City metro area, a site of racialized economic tension with the rest of the state, evidenced by campaigns such as “Unshackle Upstate.” Indeed, Binghamton’s student body is more racially diverse than Binghamton the city (Vestal, where the university is located, is 88% white), and even though the relatively low-cost public university–approximately eight thousand dollars a year for in-state tuition– serves many first-generation college students, students with generous financial aid packages, and students employed while matriculating, the city’s poverty amplifies even slight class privilege.

These long-term structural fissures have led to tensions between the university students—whom some Binghamtonians problematically peg as wealthy outsiders and/or racially target—and full-time residents, dubbed “Townies” by many students and dehumanized as the backdrop to their college experience. While students and year-round residents inhabit the same physical spaces in Binghamton, they are not in fact living the same place and they often experience, interpret, and act on the same auditory information in drastically different ways. Binghamton sounds differently to each group, in terms of the impressions and interpretations of various auditory phenomena as well as the order of importance an individual gives to simultaneous sounds at any given moment.

Embodied aural perceptions shaped by class, race, age, and differing regional experience may in fact drive many of the “town and gown” conflicts—noise complaints most obviously—and exacerbate others, particularly mutually distorted perceptions that students bring Binghamton down and that residents are, as one student cruelly stated in the campus newspaper, “creatures” from “an endless horror movie.” So how to address this divide? And how to use sound studies to do it? I knew I did not want to impose a community project on my students that did not have their buy in and creative energy behind it. I decided on a group-sourcing project that asked students to work together to design a sound-studies based community project. I envisioned the assignment as the first phase of a longer-term project, with the most workable idea serving as the basis for a full-blown service learning experience in future courses. However, the assignment proved to be pedagogically valuable in its own right, not just as a prelude to future work.

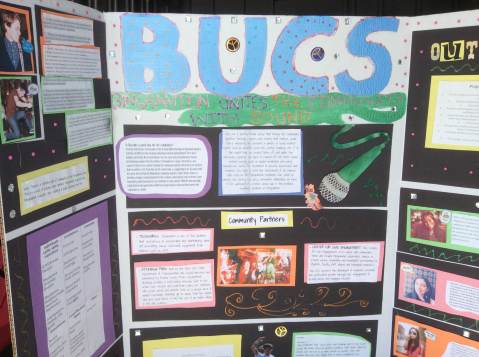

“Binghamton Unites Community Through Sound” Poster Project, Image by Author

I arranged my course around the proposal assignment, providing students with the critical thinking skills to imagine a project of this type. We began with theoretical and methodological materials that would introduce them to sound studies—none of my students were familiar with the field and its assumptions—and ground their thinking in the idea that listening is a complex sociocultural, political, and critical practice. While we read and discussed multitude of pieces on listening, the students reported four scholars as especially inspirational to the project: Yvon Bonenfant’s theorization of “queer listening” as a listening out (rather than the more normative taking in), Regina Bradley’s work on race and listening in American courtrooms that focused on how white lawyers discredit witnesses speaking patois and African American Vernacular English, Maile Costa Colbert’s artistic imagining of a “wayback sound machine,” and Emily Thompson’s work on noise and time/space/place, particularly in her new interactive “Roaring Twenties” project. Student Daniel Santos reported in a survey following the project,

The relationship between sound and time was very useful to our project; we understood the concept that no city ever sounds the same after a long period of time, and we sought to take advantage of this fact. Through our residents’ stories, we learned that Binghamton was once booming with sound from numerous, lucrative industries. Walking into a factory brought an industrial cacophony: card punchers thudded as steel was pounded against steel. However, today, a walk into these factories results in an eerie silence. We wanted our soundwalk participants to realize and become affected by this lack of and difference in sound, and raise pertinent questions: what happened to these sounds? Why is there such a large difference in sound levels? Where do I place myself within this soundscape?

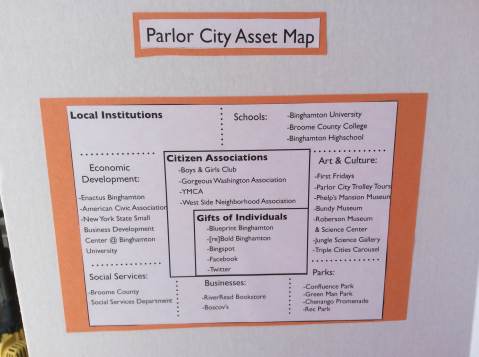

I worked with Binghamton’s Center for Civic Engagement—a model program founded in 2010—and in particular with Assistant Director Christie Zwahlen, to equip students with basic-but-solid knowledge that would enable a new understanding of community work. Zwahlen brought home two major principles to students: 1) service learning has a pedagogical component; it is important to a project’s success that students learn something through their work rather than merely donating time or skills, 2) Community engagement works best when based on identifying and mobilizing a community’s assets rather than implementing an external project addressing perceived deficits. These two concepts meshed especially well with the students’ evolving understanding of listening as multifaceted, political, and deeply impacted by temporal and spatial contexts, because it required the students to engage directly with community members and learn how to listen to their voices, histories, and needs.

For both civic engagement and sound studies, Zwahlen and I introduced students to the various methods used to solve problems and answer our most important questions. For civic engagement, Christie focused on the asset map, which forced students to think of the surrounding community in terms of its strengths rather than the weaknesses they could already readily list. This exercise not only flipped their perspective but also helped them imagine and hone their project by identifying community stakeholders who would be receptive to their inquiries.

ReSounding Binghamton Project, Image by author

In terms of sound studies, I introduced them to a multiplicity of methods through readings, experiential activities, and process writing, in particular sound provocations and sound walks. According to student Hannah Lundeen’s post-project survey, the sound walks she performed proved especially fruitful:

Initially, solving a community issue through sound seemed next to impossible. It wasn’t until sitting down and thinking about the sound studies methods of soundwalks that it became clear. I liked soundwalks because they are a way to engage anyone in sound studies. They are an easy concept to explain to people who may not have thought much about their soundscape previously. They are an active and fun way to engage all community members in listening well.

As Lundeen relates, interweaving these methods formed the foundation of their community projects, enabling their inquiries regarding understanding differences in listening, how to enable people to recognize and discuss aspects of their listening, and to provoke some kind of impactful social change.

The final third of the semester was devoted to working on the final project [Click these links for the Rubric for Final Poster Presentation we used to assess the projects as well as the assignment sheet with Tips for Successfully Completing this Project both of which I handed out on day one! ]. Following an initial period of research and discussion, students narrowed down their project ideas, identified and met in person with potential community partners–ReBold Binghamton, Binghamton’s Center for Technology & Innovation, the Parks Department and several City Council members were especially helpful– and put together their proposals, emphasizing their new understandings of listening and its relationship to space and place via community mobilization. Students prepared a 7-minute gloss of their projects for public presentation that

- identified an issue (supported by research)

- described how project addressed the issue

- presented community asset map as a foundation

- shared list of potential community partners

- discussed sound studies methodologies supporting the project

- estimated benchmarks for the project’s completion

- projected the project’s long-term outcomes

- prepared personal reflections on the process.

ReSounding Binghamton Student Presentation, Image by Shea Brodsky

Here is a sampling from the rich palette of student project pitches:

- Restoring the Pride: A public art initiative building rain-activated sound sculptures.

- BUCS: Binghamton Unites Community with Sound: A public group karaoke project.

- Safe and Sound: A “kiosk walk” of 10-interactive electronic sound art pieces that increase downtown destination traffic by day and operate as a “blue light” safety system by night.

- Blues on the Bridge Junior: A children’s music stage at one of Binghamton’s most popular yearly events.

- Happy Hour: A weekly campus radio show designed to combat seasonal depression.

- Listen Up!: Sound Month Binghamton: An annual themed digital “sound collection month” in March with accompanying “sounds of Binghamton” remix project. This project fosters community habituation to “Others’” sounds while also tracking long-term changes in the soundcape and in residents’ ideas of noise.

- A Sound Walk Through Binghamton: Historical soundwalks through several areas in Binghamton, where archival sounds of the past (some compiled from recordings, some performed) are placed in continuity and contrast with contemporary soundscapes.

Zwahlen and I understand that this iteration of the project does not constitute civic engagement as of yet. Certainly, the students raised more questions than solutions: how to work with—and equitably solicit contributions from—community members rather than organize classroom-first? How to increase community involvement on a campus that is a foreboding maze at best—and how to increase student traffic in the many sites not reached by Binghamton’s limited public transportation? Most importantly, How to share sound studies epistemology beyond the classroom, creating listening experiences that not only take differences into account but potentially re-script them?

ReSounding Binghamton Student Project, Image by Author

As we move forward with long-term development, we will undoubtedly encounter more questions. However, even at its earliest stages, I believe guiding my students to integrate sound studies methodologies with asset-based service learning provided them with a transformative experience concerning the powerful resonance of applied knowledge and sparked the kind of self-realization that leads to civically engaged citizens. It created meaningful connections between them and a local community suddenly made significantly larger. For my students, listening became more than a metaphor or an individualized act of attention, rather they began to understand its role as a material conduit of location, outreach, and connection. As an anonymous student shared in my teaching evaluations: “This class was different, but in a very good way. It has been so involved with the human experience, more so than with other classes.” In the middle of the so-called “humanities crisis,” this response points to the potential power of a civically engaged sound studies, a branch of the field combining research with praxis to reveal the role of listening in the building, maintenance, and daily experiences of diverse communities in the city spaces they mutually inhabit but often do not fully and equitably share.

—

Featured Image by Shea Brodsky, (L to R) Binghamton University Students Robert Lieng, Daniel Santos, and Susan Sherwood, Director of Binghamton’s Center for Technology & Innovation (CT&I)

—

Jennifer Stoever is co-founder and Editor-in-Chief of Sounding Out! She is also Associate Professor of English at Binghamton University and a recipient of the 2014 SUNY Chancellor’s Award in Teaching.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Sounding Out! Podcast #13: Sounding Shakespeare in S(e)oul– Brooke Carlson

Deejaying her Listening: Learning through Life Stories of Human Rights Violations– Emmanuelle Sonntag and Bronwen Low

Audio Culture Studies: Scaffolding a Sequence of Assignments– Jentery Sayers

Recent Comments