Echoes of the Latent Present: Listening to Lags, Delays, and Other Temporal Disjunctions

Listen:

Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time.

–Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse Five

On an almost visceral level, we may likewise remark that states of “latency” involve downward movement, as in the case of something falling by the wayside and lying unnoticed until its presence is felt.

— Hans Gumbrecht, After 1945: Latency as Origin of the Present

Sometime last year, during a recent deep clean of the apartment, I pulled out a wooden chest that my father built for me when I was ten, a pine-scented time capsule of that period of my life, full of assorted construction-paper projects and faded movie tickets. Buried underneath all this loose paper, set apart by a shiny laminated cover, is the first “novel” I ever wrote, our final project in fourth grade, which was really just a few typed pages folded and stapled together, held between a cardstock cover. In this book, I write about a mall janitor with magic powers, who uses his mop handle to transform villains into piles of fabric, and who time travels throughout history by way of a magic corvette (clearly, I had just seen a certain Robert Zemeckis film).

Having rediscovered this story, I am struck by the realization that my writerly voice has hardly changed. I am still drawn to the same hokey surrealism, the same comic book sensibilities, the same spirit of hand-stapled publishing projects. This is to say: I could not help but to identify in this proto-novel traces of my work to come, early impulses that echo throughout my present practice. As Lisa Robertson puts it in an interview: “Defunct forms resurface after years of latency. New work speaks with old work, as well as with the future.”

This work speaks to a recurrent theme in my life: namely, my pervasive sense of feeling out-of-sync with the world, or as Vonnegut puts it, “unstuck in time.” In this essay, I want to think about latency—essentially, the time it takes for data to transfer between two points—as a poignant extended metaphor for the temporal disjunctures of the present moment. Indeed, the frantic mantra of “being present,” as popularized among Western spiritualists by Eckhart Tolle’s The Power of Now (1997), is a kind of antiphrasis, a phrase which evokes precisely the opposite thought. In this case, the power of now simultaneously diagnoses the perils of asynchronicity. And yet, perhaps there are some counterintuitive reasons why latency might be politically productive at times, as I will discuss in the sections that follow.

Fittingly, the concept of “echoic memory” suggests that the brain acts as a kind of temporary holding tank for sounds, not unlike an old wooden chest full of memorabilia. The difference, in this case, is that echoic memory is a short-term storage system. One example of this memory structure at work is when someone asks “What did you say?” only to answer their own question after a half-second, since they are somehow able to retrieve this latent information, one might say unconsciously, from the holding tank.

As a sound artist, I am interested in multiple facets of latency, from its aesthetics to its politics, and especially its psychoacoustics, the way that sound acts tangibly upon bodies and minds. This post will examine how audio latency encapsulates the paradoxical tension between the desire for sonic immanence—in the sense of longing for an immediate experience—and the frustrations of technology, its delays and disruptions. A prime example of this tension is that you and I could be seated right beside each other and still experience a laggy phone call. The paradoxical element starts to emerge when one tries to achieve zero latency, since any signal must travel through space and time, just like Achilles and the tortoise, and thus subject itself to delay.

(Latency Commercial)

Latency, as such, is a shifty concept. By one definition, it refers to any length of interval between impulse and response, including the time it takes to respond to a handwritten letter, or, in my case, the rediscovery of an old book after twenty-something years. By another definition, latency refers to all manner of system delays, including the quality of a network connection, the time it takes for data to transfer between two points. The term might also be familiar from biology or psychology, where it refers to anything hidden or dormant that has not yet manifested, like a disease or an unconscious desire. Another context in which the term frequently shows up is laboratory studies, measuring the delay between some kind of sensory stimulus and reaction, such as a honeybee’s conditioned response to a scent. Lastly, and most importantly for the purposes of this discussion, “audio latency” refers to a very short period of delay that causes sound to lag behind imagery, or, ultimately, behind itself.

(Latency Test)

The latency test video above provides a helpful listening exercise. Though such small intervals of time, measured in milliseconds, are hard to conceptualize in the abstract, they are jarringly comprehensible as sound. With just five milliseconds of latency, a chorus effect is applied to the experimenter’s finger snap, which now sounds as though it has been placed inside a drainpipe. At ten milliseconds of latency, one can already hear two distinct transients, otherwise known as amplitude spikes, where the sound of the snap abruptly begins. By fifty milliseconds, a more dramatic delay effect emerges, and it sounds as though the finger snap is being pulled apart. This bifurcation process culminates at three hundred milliseconds, when the concept of “latency” begins to overlap with that of “delay,” such that there are now two distinct snaps.

(Network Audio Latency)

Latency, then, can be both a problem and an intentional effect. If you have ever tried to record an acoustic guitar, or a vocal track, on an outdated computer, you may have encountered this phenomenon in the form of a technological issue. Everything is plugged in and ready to go, the active track in your audio workstation is armed, headphone monitoring is turned on, and you begin to strum or sing. To your dismay, the sound you hear from the computer starts to fall behind the sounds you are making in the real world. Not only does the recording sound off, and out of time, but it becomes physically impossible to play an instrument when your fingers and ears are thrown out of alignment, like attempting to ride the backwards brain bicycle.

(Guitar Latency)

Diagnosing and solving latency issues is another game entirely: lowering the buffer size, enabling delay compensation, or simply going rogue and recording without monitoring playback, with the hope of nudging the recording back into alignment after the fact. In a home studio, sometimes a full half of the day’s recording session will get swallowed up by these technological battles, trying to shrink latency down to smaller and smaller increments. Given the sheer number of YouTube tutorials dedicated to reducing latency, it is clear how pervasive this issue is for musicians and audio engineers.

(Singing)

As Mitch Gallagher suggests in the video above, some singers can detect latency as short as three milliseconds, which can significantly throw off their performance. If you have ever been in a Zoom call where you can hear yourself through the other person’s speaker, this feeling will be all too familiar. This is not unlike a less aggressive form of speech jamming, which refers to a kind of crowd-control tactic employed by the military in order to break someone’s concentration using delayed audio. Known as “acoustic hailing and disruption” (AHAD), this process makes it very difficult to speak consistently, because a live recording of one’s voice is beamed instantaneously back at the speaker with a certain length of delay, in milliseconds, as demonstrated in a 1974 piece by Richard Serra and Nancy Holt, called Boomerang. As with the backwards brain bicycle, but perhaps far less benign, latency can take the form of weaponized confusion. The same principle, however, is used for positive ends in the case of Delayed Auditory Feedback (DAF) devices which people who stutter use as an assistive technology.

Being out of sync with the present moment, in other words, can be both disorienting and orienting. Latency can mean one thing for a musician trying to lay down a vocal track, but something else entirely for a political protestor attempting to address a crowd, or someone consciously manipulating their own speech patterns.

As a form of sonic violence, weaponized latency has an ancient Greek precedent in the myth of Echo, a nymph who is cursed with repeating the last words spoken to her, such that she can no longer express herself. This archetypal figure, both gendered and pathologized, embodies a form of perpetual exclusion from discourse. Speaking to this subject, Katie Kadue underlines a pertinent quote in literary critic Barbara Johnson’s essay, “Muteness Envy”: Feminist criticism has been pointing this out for at least thirty years. But why is female muteness a repository of aesthetic value? And what does that muteness signify?” At the same time as Echo’s curse represents a metaphorical silencing, it also signifies something else in its insistence on rhetorical conformity, denying and dislocating her from the present of her own thoughts—a “living death,” in the words of Rebecca Solnit.

If patriarchy loves the sound of its own voice, then capitalism loves the beat of its own drum, which speeds up or slows down depending on competing urgencies. Ultimately, this manufactured present moves much faster than the embodied present, moving at such a rate that one cannot even decipher the words that one is meant to repeat.

To operate outside of this temporal structure then, is to move and make sound at a tempo that does not match the dominant rhythms of hypercapitalism. To this end, Fred Moten quotes the following passage from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952): “Invisibility, let me explain, gives one a slightly different sense of time, you’re never quite on the beat. Sometimes you’re ahead, sometimes behind.” Moten calls this “improvisational immanence,” characterized by “disruptive surprise.” Bringing these concepts together, Fiamma Montezemolo’s Echo (2014) is a work of video art that “disrupts and dissents from the ways that race and gender are produced and experienced through sound and listening,” to quote Lois Klassen and Gabriela Aceves Sepúlveda. It does so by assembling an archive of earlier artworks in which women share their personal testimonies of discrimination and inequality, along with hopes for the future. Through this archive, Montezemolo helps these voices to reverberate, latently, in the present. With this in mind, one begins to hear how latency can function both as a barrier, as well as a boon, to expressivity. Especially in those cases where the original sound might have gone unheard, or was actively obstructed, there is always the possibility of a disruptive re-sounding.

In practice, audio latency can often feel like a curse, and it is difficult to see the upsides. In the recording studio, it can turn even the most fluid riff into a halting mess, interrupting creative flow with high-tech tedium. As Rebekah Wilson points out in her study of networked music performances, these technological failures have “aesthetic implications” beyond a mere computer glitch, insofar as rhythmic music is much harder to coordinate over long distances; more than anything, latency “affects time keeping and human-level rhythms” (Wilson 2020).

Must audio latency always be met with resistance, however? No doubt, such glitches could be treated as opportunities for creative misuse. What might happen, for example, were someone to treat these rhythmic glitches as an intentional musical element or a compositional technique reminiscent of a musical canon? As discussed in a previous post, Eleni Ikoniadou presents such thought experiments in The Rhythmic Event (2014), where the author asks what alternative modes of expression might arise when we are able to “twist chronology and rethink the latent tendencies of the event, outside the tyranny of the ticking clock” (68). Latency takes us off the grid and into the abstract, unquantized space of the timeline, where notes are free-floating, and other temporalities become possible, as in Ellison’s description of the jazz musician who plays behind or ahead of the beat, while still remaining “in time,” moving within a loose present that is spacious enough for jazz artists to name it “the pocket.”

(Latency Sucks)

Pondering the relationship of “latency” to the present moment, I am reminded of Boris Groys’ definition of the contemporary: “To be con-temporary does not necessarily mean to be present, to be here-and-now; it means to be ‘with time’ rather than ‘in time.’” For the percussionist whose dexterity has been scrambled by latency issues, to be a “comrade of time,” in the words of Groys, would mean “collaborating with time, helping time when it has problems, when it has difficulties.” This is a counterintuitive approach, however, which does not call for latency to be fixed, necessarily, but rather to be adopted as a political and aesthetic strategy.

The laggy outbursts of latency belong to the anti-capitalist “ritual of wasting time,” in resistance to “contemporary product-oriented civilization,” which would have us chase ultra-low latency for the sake of faster sports betting and stock trading. This ritualistic rejection of capitalist time resonates with Kemi Adeyemi’s description of “strategic pattern interruptions,” in a previous article, where the author shows how “lean” (a narcotic drink consumed by some rappers) is absorbed into the slowed-down aesthetics of their music, in objection to “the demands the neoliberal state places on the black body.” In this way, Adeyemi underscores the racial politics of latencies, particularly in the way that the “dissociative pleasures controlled substances offer to black people have been historically criminalized, and radically different sentencing guidelines continue to be handed down,” depending on the drug.

Where the cocaine-fuelled algorithmic traders of Wall Street chase a asymptotic present in their attempt to reach zero latency (transfers are now measured in picoseconds), contemporary sound artists might explore more audaciously the latent present, wherein one moment, one sound, is always imbricated in the next. To quote Groys once more: “we are familiar with the critique of presence, especially as formulated by Jacques Derrida, who has shown—convincingly enough—that the present is originally corrupted by past and future, that there is always absence at the heart of presence.”

Such absent presences are reflected in one of the secondary definitions of latency (as concealment). For instance, Alan Licht references Alvin Lucier’s famous sound art piece, I Am Sitting in a Room, as an example of a room’s latent resonant frequencies, which are amplified via a feedback loop. Aptly, room tone is also referred to as “presence” in the film industry. Lucier’s piece resonates with Groys’ model for the prototypical time-based artist: Sisyphus. Like the happy boulder-roller, Lucier commits to a process of absurd repetition, and reveals the present to be, in Groys’ words, “a site of the permanent rewriting of both past and future.” In the case of Serres and Holt’s experiment in Boomerang, this rewriting is also an overwriting of thought, with latency preventing the speaker from formulating her next sentence. As if to evoke the dislocation of a time traveler, at one point Holt says, “I am not where I am.” With the undercurrent of cruelty running throughout this performance piece, the artists demonstrate the disembodying effects of latency and its potency as a metaphor for systemic threats to women’s self-expression.

Groys also mentions Francis Alÿs’ animated film, Song For Lupita (1998) in which a woman pours water back and forth between two glasses, in a gesture of anti-capitalist counterproductivity. Here, it is worth noting the discrepancy in attitudes between the tragic male heroism of Sisyphus and the cursed mimicry of Echo, whereby one is celebrated for his resistance in the face of futility, whereas the other is not often mythologized in the same way, though women working in contemporary sound art have begun to redress this representational imbalance by mobilizing the concept of subversive difference. The Alÿs animation linked above takes a similar but slightly different approach, of subversive indifference, where pointless repetition pushes back against capitalism’s intolerance of delay (unless it serves the status quo, e.g., climate inaction). Underscored by lyrics which repeat the phrase “mañana, mañana,” the score reflects this theme of deferral while also indicating that actions taken (or not taken) today might have a delayed effect tomorrow.

(Phone Latency)

As I work through the second draft of this essay, I can hear the boomerang of latency returning to me, offering another chance to rethink, reformulate, reword, and re-listen. Much like how latency has the potential to alienate performers from the flow of a recording session, it can often feel to me as though I am permanently trailing behind the sonic present, caught in its slipstream, an exasperated Achilles chasing after the tortoise of time. As I type these words, I can just barely sense the time it takes the letters to leave my fingers through the keyboard and appear on screen. I think about the illusion of instantaneity, and how the typewriter was a constant reminder of this delay between the exciter of the key and the resonator of the page. Suddenly I can hear the letters smacking the screen. I feel anxiously attuned to the basic math of my estrangement, knowing that sound travels at just over a thousand feet per second.

As a matter of fact, this means that my sonic present and yours are subject to a proximity effect, depending on who is closer to the megaphone. Sometimes it can feel like one is always trying to make sense of a belated reality. And yet, old books are often showing up just when they are needed most, and it is in this way that “intense collective potentials hover as forms in the present,” in the words of Lisa Robertson. The poet reminds us that not only is every historical moment charged with the latent potential to act, but that such political actions are latent in language, surviving as poems and essays “across long durations,” ready to reach someone in a new instant.

—

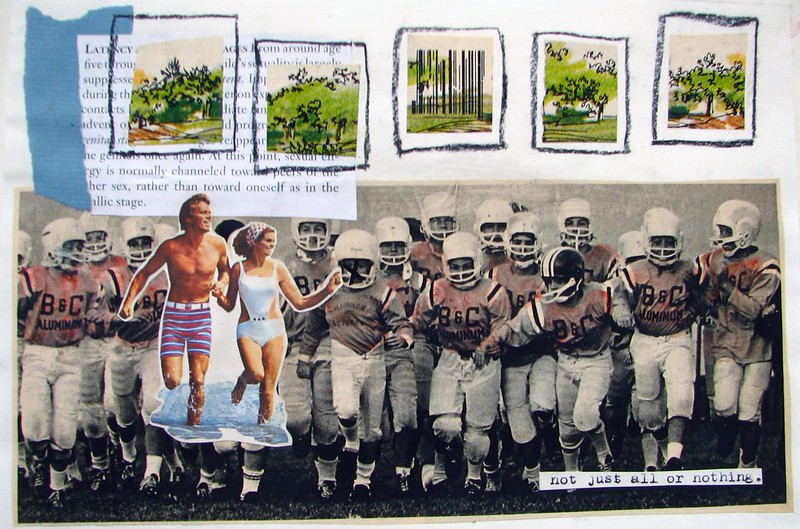

Featured Image: “Minema Maxima” by Laurence Chan (2015) CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED

—

Matthew Tomkinson is a writer, composer, and postdoctoral research fellow based in Vancouver. He holds a PhD in Theatre Studies from the University of British Columbia, where he studied sound within the Deaf, Disability, and Mad arts. His current book project, Sound and Sense in Contemporary Theatre: Mad Auralities (Palgrave Macmillan, 2024), examines auditory simulations of mental health differences. As a composer and sound designer, he has presented his work widely throughout the US, Canada, Germany, Austria, Ireland, Portugal, Bosnia, Kosovo, and the UK, collaborating with companies such as Ballet BC, Company 605, Magazinist, and the All Bodies Dance Project. Matthew lives on the unceded territories of the Coast Salish peoples, including the qʼʷa:n̓ƛʼən̓ (Kwantlen), q̓ic̓əy̓ (Katzie), SEMYOME (Semiahmoo), and sc̓əwaθən məsteyəx (Tsawwassen) Nations.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

TiK ToK: Post-Crash Party Pop, Compulsory Presentism and the 2008 Financial Collapse–Dan DiPiero

Straight Leanin’: Sounding Black Life at the Intersection of Hip-hop and Big Pharma–Kemi Adeyemi

My Time in the Bush of Drones: or, 24 Hours at Basilica Hudson–Robert Ryan

“Music More Ancient than Words”: W.E.B. Du Bois’s Theories on Africana Aurality— Aaron Carter-Ényì

The Noises of Finance–Adriana Knouf

Recent Comments