Xicanacimiento, Life-giving Sonics of Critical Consciousness

This series listens to the political, gendered, queer(ed), racial engagements and class entanglements involved in proclaiming out loud: La-TIN-x. ChI-ca-NA. La-TI-ne. ChI-ca-n-@. Xi-can-x. Funded by an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation as part of the Crossing Latinidades Humanities Research Initiative, the Latinx Sound Cultures Studies Working Group critically considers the role of sound and listening in our formation as political subjects. Through both a comparative and cross-regional lens, we invite Latinx Sound Scholars to join us as we dialogue about our place within the larger fields of Chicanx/Latinx Studies and Sound Studies. We are delighted to publish our initial musings with Sounding Out!, a forum that has long prioritized sound from a queered, racial, working-class and “always-from-below” epistemological standpoint. —Ed. Dolores Inés Casillas

—

In the past year, we, Esther, a first-generation profesora in Latinx culture and feminist studies in Chicago and Kristian, an L.A-raised Xicano de letras pursuing a doctoral degree in Santa Barbara, engaged in a multi-synchronous dialogue on the life-giving sonics of our critical consciousness. This Xicanacimiento, as theorized in Kristian’s current writing and in conversation with Irene Vasquez and an emerging generation of Chicana/o scholar-educators, refers to the incomplete process and life-giving knowledge forged in the socio-political and pedagogical activities of Chicanx worldmaking.

SO! writers note music listening as a powerful site for critical thinking. Erika Giselda Abad, for instance, teaches the Hamilton Mixtape so her Latinx students may “hear [their stories] from people who look and sound like them.” We reflected on the pedagogical implications of our music listening that informed our coming-into-critical consciousness. In this diálogo, we developed a playlist through experimenting with our sonic memories through the poetics of our rasquache sensibilities. Gloria Anzaldúa suggests something similar with notes from Los Tigres, Silvio Rodriguez, and others in La Frontera. Our auditory imaginary echoes our evolving conocimiento toward spiritual activism.

Here, we offer our musical resonances as shaped by our gendered, place-based, and generational Xicanx experiences as a pathway to hear the auditory dimensions of Xicanacimiento. Our listening is thus counter-hegemonic or a “brown form of listening” as suggested by D. Inés Casillas, “a form of radical self-love, a sonic eff-you, and a means of taking up uninvited (white) space,” when this listening evolves critical anti-imperialist and feminist consciousness that hears 500 years of opresión y resistencia.

Diverging from the mixtape genre, our Xicanacimiento playlist seeks to convey something beyond connection and emotion towards a sustained affective state. Instead of a sonic moment, we hear a sonic stream; a subaltern auditory repertoire that is multi-directional and open to expansion by any and all interpellated Xicanx ears.

Kristian: Tuning-in to Xicanacimiento is a symbiosis of feeling and listening to La Chicanada from Califas to all corners of Aztlán unearthed. I was raised to the sounds of my father’s rancheras played in his truck and the hip-thumping rhythms of bachata and reggaetón played in my mother’s kitchen after a workday.

Yet, my love for UK anarcho-punk and US hardcore punk developed in defiance of public schooling and of a disaffected civil society. As a youth during the Great Recession, a future without higher education meant prison, the military, death by overdose, or the eternal damnation of working the Los Angeles service industry. I thrashed in sound; numbing my ears with noise, bruising in the mosh pit; bearing witness to minors as mota and alcohol addicts; pierced by the cries of police sirens breaking up our communion.

I found refuge in Xicanacimiento as a community college student and as a transfer at UC Los Angeles. I came into Xicanx consciousness by studying Mexican anarchists and Chicanx organizing. As a MEChistA, I came to listen to the ways local elders, youth, organizers, and agents of social transformation in Los Angeles identified their struggle with land, life, and spirit. My primer to social movements gave me language, and it was MEChistAs who offered me a new soundtrack against the escapism of the Los Angeles punk scene. The resonances of marchas, fiestas, and the songs of danza azteca oriented me into a new modality of listening. Xicanacimiento was the sonic web of these social and cultural practices, rooted in my auditory encounters with the verses of Quetzal, the biting guitars of Subsistencia, the rhythms of Quinto Sol, and the lyrical narratives of Aztlán Underground. The life-giving sonics of Xicanacimiento grazed against my wounded sonics of broken glass, nos tanks, drunk noise, and the cacophonous affair of a raided gig as intoxicated Latinx youth disperse into the discordant symphonies of the urban soundscape.

Esther: I listen as a campesina migrante translocada from Jalisco to California, Texas, and Illinois. Some twenty years ago, while attending Cal State en el Valle Central, I heard Xicanacimiento as concientización; an evolving awareness about la lucha obrera, the open veins of Latinoamerica and my place within the interlocked hierarchies of race, class, and gender in US society. With Chicanx and brigadista musics I felt connected to la lucha and acquired the language to name capitalist imperialism rooted in white supremacy as the enemy of humanity and Pachamama.

My early sonic memories include the sequence of my Alien number, the urging tones of radio hablada discussing Prop 187 (insisting we were aliens), Prop 227 (banning our language), and reports of Minuteman harassing la raza. I was immersed in listening; my mother’s sobremesa, my sister’s Temerarios at 5 am, Selena on the school bus, and 90s hits-from Chalino to Morrissey-on Columbia House CDs I traded with my older brother. Among other norteñas, La Jaula de Oro, the theme song of the diaspora of papás mexicanos, played at random-at the marketa, en los files, in passing cars, and so on…- to remind us of my father’s sacrificio en el norte caring for 500 dairy cows, six days a week, in two 5-hour shifts, to provide us el sueño americano.

I studied music in college, playing jazz and orchestral bass until the racist and sexual harassment targeting my young Latina body turned me away. I left the scene but continued my communion with music through library loans, traveling vendors, and trips to Amoeba. In reggae and canción nueva I found otros mundos posibles in the upbeat, cariño in 2 over 3, and the poetics of black and brown history; manos abiertas, muchas manos.

In 2002, “El Rasquache Rudo” a poet from the Rudo Revolutionary Front brought me sounds from Azltán; the UFW unity clap rallying in Modesto, a recitation by José Montoya in Sacramento, and brigadista music synergizing the 1492 quincentennial resistance with the uprising of the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN). As Omar Marquez argues, the Zapatista uprising shifted Chicano ideology to speak from the position of a living indigenous present; still loud in the work of Xicanx activists like Flor Martinez. Into the 21st century, Aztlán Underground, Manu Chao, and Todos Tus Muertos, among others, soundtracked our protests against the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq.

Julieta Venegas’s distinctly vulnerable voice over the controlled chaos of ska and Martha Gonzalez’s tension over the wall of sound that is Quetzal, was transformative as I heard In Lak’ech; hearing in their voices possibilities for my Chicana existence.

Some of these selections anchor my first-year lectures at the University of Illinois in Chicago, where most of my students are working-class Latinx and Black. I do this with the intention of “opening affective pathways toward Xicanacimiento” as Kristian offered, and to insist on the point that Latina/o/x Studies is to be a critical, anti-hegemonic, subaltern field of study that hears a history from el mundo zurdo.

Outro:

In a gesture to deconstruct the term Xicanacimiento, one might think of the words “renacimiento”and “conocimiento.” What might emerge is a “regenerative force” and “collective knowledges” in consideration to how we listen, what resonances are made, and what sounds we inhabit when Xicanacimiento is invoked or felt as sound. Tuning into this auditory imagination guides the listener to a myriad and select decisions of what constitutes the Xicanx resonance for the local sonic geographies and the soundscapes which emerge from music. This curated sonic experience is one where voice, instrument, memory, and affect intersect.

—

Featured Image by Jennifer Lynn Stoever

—

Esther Díaz Martín is a researcher and educator in the Latin American and Latino Studies and the Gender and Women’s Studies program at the University of Illinois in Chicago. At present, she is working towards finishing her manuscript Latina Radiophonic Feminism(s) which seeks to amplify the acoustic work of popular feminism in contemporary Spanish-language radio and Latina podcasting.

Kristian E. Vasquez is a Xicano writer, poet, and zinester born and raised in Los Angeles, California currently pursuing a doctoral degree in Chicana and Chicano Studies at UC Santa Barbara. His research on the affects, sounds, and semiotics of La Xicanada expands the concept of Xicanacimiento, centering the affective force of expressive culture.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Ronca Realness: Voices that Sound the Sucia Body—Cloe Gentile Reyes

SO! Podcast #74: Bonus Track for Spanish Rap & Sound Studies Forum—Lucreccia Quintanilla

“Heavy Airplay, All Day with No Chorus”: Classroom Sonic Consciousness in the Playlist Project—Todd Craig

Deep Listening as Philogynoir: Playlists, Black Girl Idiom, and Love–Shakira Holt

Mixtapes v. Playlists: Medium, Message, Materiality–Mike Glennon

SO! Amplifies: Memoir Mixtapes

Could I Be Chicana Without Carlos Santana?–Wanda Alarcón

Tape Hiss, Compression, and the Stubborn Materiality of Sonic Diaspora–Christopher Chien

Sounding Out! Podcast #28: Off the 60: A Mix-Tape Dedication to Los Angeles–J.L. Stoever

“Oh how so East L.A.”: The Sound of 80s Flashbacks in Chicana Literature–Wanda Alarcón

“Heavy Airplay, All Day with No Chorus”: Classroom Sonic Consciousness in the Playlist Project

For a number of semesters, I invited composition students to explore the idea of using the mixtape as a lens for envisioning a writing assignment about themselves. Initially called “The Mixtape Project,” this auto-ethnographical assignment employed philosophies from various scholars, but focused on Jared Ball and his concept of the mixtape as “emancipatory journalism.” In I Mix What I Like!: A Mixtape Manifesto, Ball pushed readers to imagine the mixtape as a counter-systematic soundbombing, circumventing elements of traditional record industry copyright practices (2011).

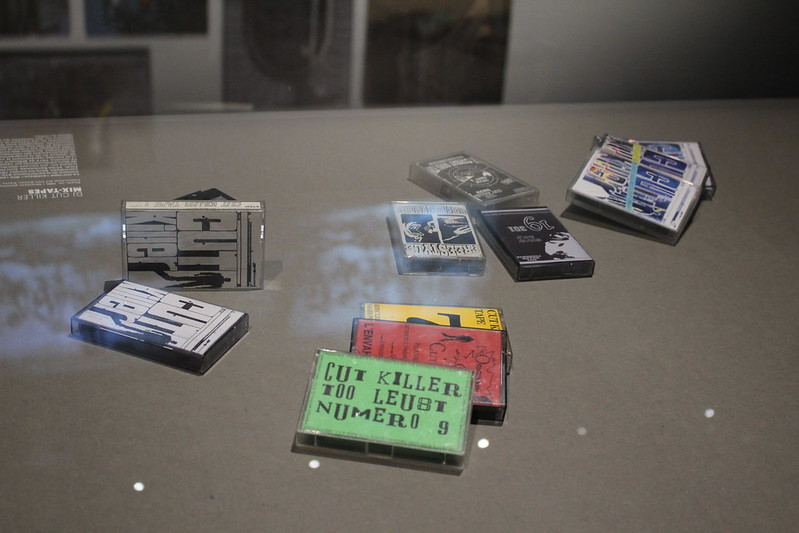

Essentially, a DJ could use a myriad of songs from different artists and labels to curate a mixtape with a desired theme and overarching message, then distribute the mixtape as a “for promotional use only” artifact. Throughout the 1980s, but predominantly in the 1990s and early 2000s, many DJs used mixtapes as the medium to promote their DJ brands and generate income. It wasn’t long before labels began to give hip-hop DJs record deals to release “album-style” mixtapes where the DJs record original content from artists made specifically for the DJ album (see DJ Clue, Funkmaster Flex, Tony Touch). This idea evolved into producer-based compilation albums, best depicted today by global icon DJ Khalid. Rappers also hopped on the mixtape wave, using the medium to jump-start their careers, create a “street buzz” around their music, and ultimately gauge the success of certain songs to craft and promote upcoming albums.

Image by Flickr User Backpackerz: “K7 mixtape – Exposition Hip Hop, du Bronx aux rues arabes (Institut du monde arabe)” (CC BY-SA 2.0)

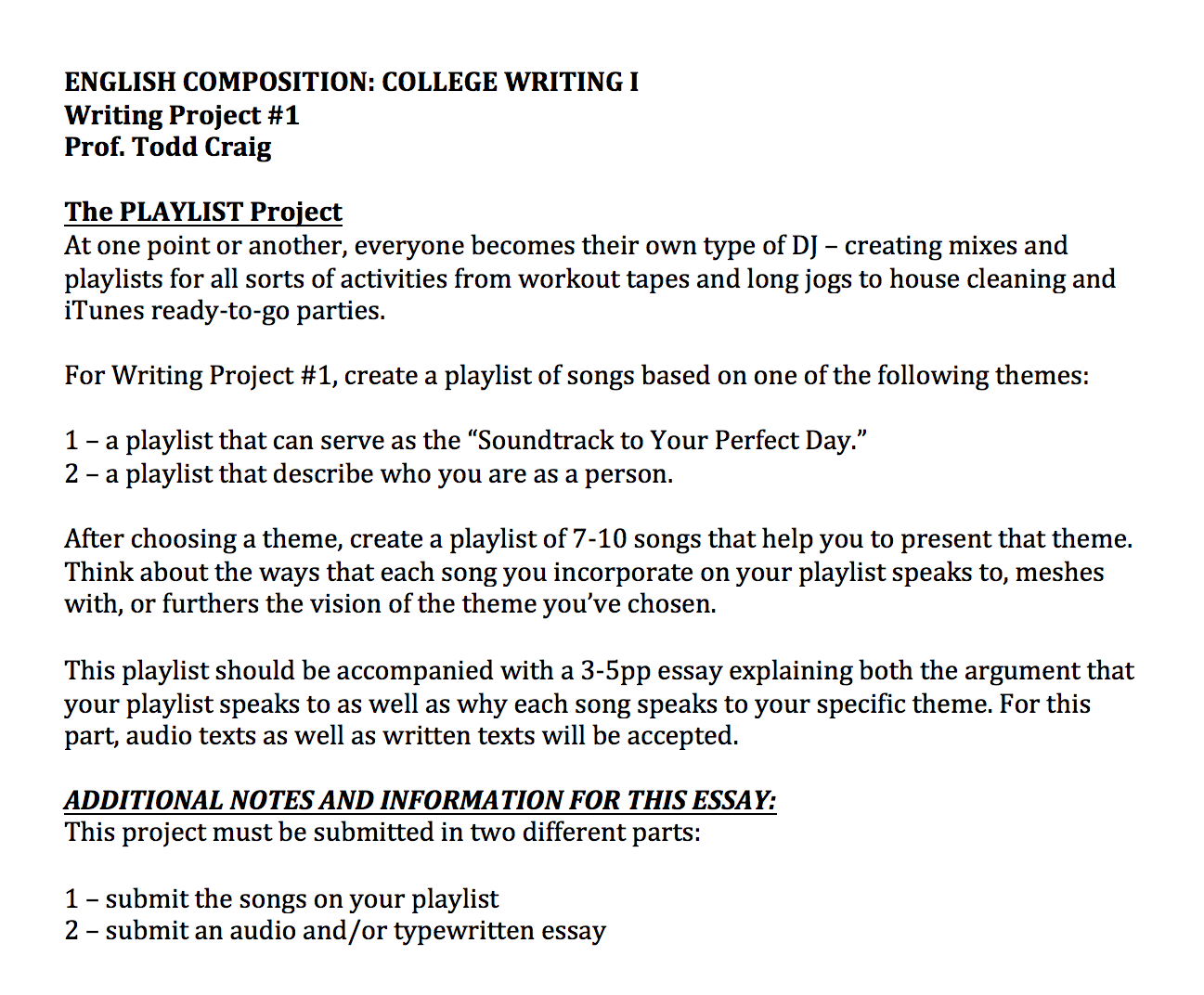

The assignment revolved around mixtape framework in the earlier portion of my teaching career. Most recently, I began to realize as my students evolve (and I simultaneously age), that the “mixtape” – a sonic artifact distributed on cassette tape or CD – is becoming more remote to students. This thinking led to revising the assignment with a more contemporary twist. Thus, “The Playlist Project” was born: the first in a set of four major writing projects in a first-year writing classroom. The ultimate goal of the assignment was to immediately disrupt students’ relationships with academic writing, and to help them (re)envision the ways they embrace some of the cultural capital they value in college classrooms. Be clear, this was a particular type of mental break for students, a shift that was welcomed yet also uncomfortable for them.

“I Get It How I Live It”: Framing and Foregrounding the Assignment Set-Up

The course started with readings on plagiarism, intertextuality, and the hip-hop DJ’s use of sampling, curating, and storytelling. Next were readings by hip-hop artists describing their creative process and detailing their artistic choices sonically. These early readings helped pivot students from their stereotypical notions of what college writing courses – and writing assignments – looked like, and how they could enter scholarly discourse around composing. This conversation was foregrounded in students’ knowledge that they bring with them into the new academic space in the college classroom. My goal was to really focus on student-centered learning and culturally relevant pedagogy; ideally, if you are immersed in hip-hop music and culture, I want you to share that knowledge with the class. This sharing begins to create a community of thinking peers instead of a classroom with an English professor and a bunch of students who have to take the course “cuz it’s required in the Gen Ed, so I can’t take anything else ‘til I pass this!”

My research is entrenched in both hip-hop pedagogy and culture, specifically looking at the DJ as 21st century new media reader and writer. I liken my role as instructor to that of the DJ: a tastemaker and curator for the ways we understand sonic sources we know, and couple them with new and necessary soundbites that become critical to the cutting edge of the learning we need. I’ve engaged in the craft of DJing for more than half of my life, and use DJ practices as pedagogical strategies in my classroom environments.

DJ Rupture, Image by Flickr User JD A (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The outcome of this curatorial moment was “the Playlist Project.” Students were asked to create their own playlists, which served as mixtapes that either “described the writer as a person” or “depicted the soundtrack to the writer’s perfect day.” This assignment was due during Week 6 of a 16-week semester, and was the first major writing assignment within the course. The assignment called for two specific parts: an actual playlist of the songs and an essay which served as a meta-text, describing not only the songs, but also the reasons why the songs were chosen and sequenced in a specific order. As an example, the guiding text we used was a DJ mixtape I created called “Heavy Airplay, All Day.”

“Heavy Airplay, All Day with No Chorus”: DJ Mixtape by Todd Craig

My playlist was a DJ-crafted tribute to a family friend who passed away in the summer of 2017: Albert “Prodigy” Johnson, Jr. Hearing the news of his untimely death reverberated through my psyche on that warm June afternoon; I remember meeting Prodigy when I was 15 years old. Many avid hip-hop listeners not only know Prodigy as one of the signature vocalists of the 1990s New York hip-hop sound, but also as one of the premier lyricists responsible for a shift in sonic content from emcees in New York and globally. His voice is one of the most sampled in hip-hop music.

One of the most anticipated moments of the mid 1990’s was the release of Prodigy’s first solo album, H.N.I.C. P was already shaking the industry with his lethal and bone-chilling visuals in his verses. But everyone knew he was on his way to dominance upon hearing the single “Keep it Thoro.” On this Alchemist-produced record, P basically broke industry rules in regards to typical hip-hop song construction; his verses were longer than the traditional 16-bar count, and the song had no chorus.

He returned to hip-hop basics: hard-hitting rhymes with undeniable visuals served atop a sonic landscape that kept everyone’s head nodding. P ends the song with the classic line “and I don’t care about what you sold/ that shit is trash/ bang this – cuz I guarantee that you bought it/ heavy airplay all day with no chorus/ I keep it thoro” (Prodigy 2000).

It was only right for me to create a tribute mixtape for Prodigy. And it felt right to start the Fall 2017 semester with the Playlist Project that used a shared text that celebrated and honored his memory. It highlighted the soundtrack to my perfect day: having my friend back to rewind all the memories that come with every song.

“I Got a New Flex and I Think I Like It”: (Re)inventing Mixtape Sensibilities in the Comp Classroom

The Playlist Project was aimed at achieving three different outcomes. The first goal was to invite students to use audio sources to envision a soundscape that explains a thread of logic. These sonic sources would hold as much value in our academic space as text-based sources, and would allow them to (re)envision what “evidence-based academic writing” looks like. Thus, students could utilize their own cultural capital to negotiate sound sources of their choosing.

The second was to get students to use DJ framework to think about sorting, sequencing and organization in writing. In our class discussions, one of the critical objectives was to get students to understand the sequencing of divergent sound sources could drastically alter the story one is trying to tell. Overall aspects of mood, tone, and pacing all become critical components of how a message is expressed in writing, but it becomes even more evident when thinking about the sonic sources used by a DJ. Each song – a source in and of itself – is a piece of a puzzle that constructs a picture and tells a story. Starting with one source can create a completely different effect if it is reconfigured to sit in the middle or the end. Explaining these sonic choices in text-based writing would be the second step in the assignment.

The second was to get students to use DJ framework to think about sorting, sequencing and organization in writing. In our class discussions, one of the critical objectives was to get students to understand the sequencing of divergent sound sources could drastically alter the story one is trying to tell. Overall aspects of mood, tone, and pacing all become critical components of how a message is expressed in writing, but it becomes even more evident when thinking about the sonic sources used by a DJ. Each song – a source in and of itself – is a piece of a puzzle that constructs a picture and tells a story. Starting with one source can create a completely different effect if it is reconfigured to sit in the middle or the end. Explaining these sonic choices in text-based writing would be the second step in the assignment.

Finally, students would engage in editing by joining both sound and text based on a theme they have selected. Again, sequencing becomes a critical DJ tool translated into the comp classroom. Using this pedagogical strategy echoes the ideas of using DJ techniques such as “blends” and “drops” as viable teaching tools (see Jennings and Petchauer 2017). Students would need to critically think through an important question: in creating the playlist, how does one manipulate and (re)configure sound to create a sonic landscape that “writes” its own unique story?

“But Does It Go In the Club?”: Outcomes and Initial Findings of The Playlist Project

The first iteration of the Playlist Project bore mixed results. Students found it difficult to think of this project as one whole assignment consisting of three different parts. Instead, they envisioned each of the three different pieces as isolated assignments. So the playlist was one part of the assignment. They picked the songs they liked, however ordering and sequencing to convey a logical theme or argument fell from the forefront of their composing. The essay then became its own piece divorced from the organic creation of the playlist. Thus, students weren’t “engaged in telling the story of the playlist.” Instead, students were making a playlist, then summarizing why their playlists contained certain songs.

For students who were more successful integrating the elements of the assignment, we were able to have rich and fruitful classroom conversations about both selection and sequencing. For example, one student chose the theme of “the Soundtrack to the Perfect Day.” Within that theme, the student chose the song “XO TOUR Llif3” by Lil Uzi Vert.

In the song’s hook, he croons “push me to the edge/ all my friends are dead/ push me to the edge/ all my friends are dead” (Vert 2017). When this song came up in class discussion, we were able to have a formative conversation around the idea that a perfect day entailed all of someone’s friends being “dead.” This also sparked a conversation about the double meaning of the quote; it didn’t stem from traditional print-based sources, but instead arose from a student-generated idea based in the cultural capital of the classroom community. In this moment, I was able to learn more from students about the meteoric rise in relevance of both the artist and the song which seemed to depict an extreme darkness.

“Big Big Tings a Gwaan”: Future Tweaks and Goals for The Playlist Project

Moving forward with this assignment, I have considered breaking the assignment up into three pieces for more introductory composition courses: constructing the playlist, sequencing the playlist, and writing the meta-text. In this configuration, the meta-text would truly become the afterthought (instead of the forethought) of the sonic creation. As well, more in-depth soundwriting could emanate from the playlist construction, manipulation, (re)sequencing and editing. I also plan to use the assignment with a more advanced-level composition course to gauge if the assignment unfolds differently. Using an upper-level course to attain the trajectory of the assignment may be helpful in walking backwards to calibrate the assignment for students in introductory-level classes.

Another objective will be to move away from just a “playlist” and back into a “digital mixtape” format, where the playlist songs and sequencing become the fodder for a one-track, “one-take” DJ-inspired mixtape. While students don’t have to be DJs, creating a singular sonic moment digitally may imbed students in marrying the idea of soundwriting to depicting that sonic work in a meta-text. This work may also engage students in constructing sonic meta-texts, thereby submersing themselves in soundwriting practices. This work can be done in Audacity, GarageBand and any other software students are familiar with and comfortable using.

—

Featured Image: By Flickr User Gemma Zoey (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

—

Dr. Todd Craig is a native of Queens, New York: a product of Ravenswood and Queensbridge Houses in Long Island City. He is a writer, educator and DJ whose career meshes his love of writing, teaching and music. Craig’s research examines the hip-hop DJ as twenty-first century new media reader and writer, and investigates the modes and practices of the DJ as creating the discursive elements of DJ rhetoric and literacy. Craig’s publications include the multimodal novel tor’cha, a short story in Staten Island Noir and essays in textbooks and scholarly journals including Across Cultures: A Reader for Writers, Fiction International, Radical Teacher and Modern Language Studies. He was guest editor of Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education for the special issue “Straight Outta English” (2017). Craig is currently working on his full-length manuscript entitled “K for the Way”: DJ Literacy and Rhetoric for Comp 2.0 and Beyond. Dr. Craig has taught English Composition within the City University of New York for over fifteen years. Presently, Craig is an Associate Professor of English at Medgar Evers College, where he serves as the Composition Coordinator and City University of New York Writing Discipline Council co-chair. He also teaches in the African American Studies Department at New York City College of Technology (CUNY).

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

The Sounds of Anti-Anti-Essentialism: Listening to Black Consciousness in the Classroom- Carter Mathes

Making His Story Their Story: Teaching Hamilton at a Minority-serving Institution–Erika Gisela Abad

Deejaying her Listening: Learning through Life Stories of Human Rights Violations– Emmanuelle Sonntag and Bronwen Low

Audio Culture Studies: Scaffolding a Sequence of Assignments– Jentery Sayers

Deep Listening as Philogynoir: Playlists, Black Girl Idiom, and Love–Shakira Holt

Recent Comments