Queer Timbres, Queered Elegy: Diamanda Galás’s The Plague Mass and the First Wave of the AIDS Crisis

Welcome to the final week of our February Forum on “Sonic Borders,” a collaboration with the IASPM-US blog in connection with this year’s IASPM-US conference on Liminality and Borderlands, held in Austin, Texas from February 28 to March 3, 2013. The “Sonic Borders” forum is a Virtual Roundtable cross-blog entity that will feature six Sounding Out! writers posting on Mondays through February 25, and four writers from IASPM-US, posting on Wednesdays starting February 6th and ending February 27th. For an encore of weeks one through four of the forum, click here. And now, while we regret to inform you that Art Jones’s dispatch from Pakistan must be re-booked at a later date, the show must go on . . .and I am thrilled that writer and Ph.D. student Airek Beauchamp is stepping in as our closing act. Make no mistake, he brings the pain! Once again, Sounding Out! gives you something you can feel. –JSA, Editor-in-Chief

Welcome to the final week of our February Forum on “Sonic Borders,” a collaboration with the IASPM-US blog in connection with this year’s IASPM-US conference on Liminality and Borderlands, held in Austin, Texas from February 28 to March 3, 2013. The “Sonic Borders” forum is a Virtual Roundtable cross-blog entity that will feature six Sounding Out! writers posting on Mondays through February 25, and four writers from IASPM-US, posting on Wednesdays starting February 6th and ending February 27th. For an encore of weeks one through four of the forum, click here. And now, while we regret to inform you that Art Jones’s dispatch from Pakistan must be re-booked at a later date, the show must go on . . .and I am thrilled that writer and Ph.D. student Airek Beauchamp is stepping in as our closing act. Make no mistake, he brings the pain! Once again, Sounding Out! gives you something you can feel. –JSA, Editor-in-Chief

—

At dinner a few days later in the Village Jarrod tells me that he cries whenever anyone says that they really ‘get’ his work. Because his work is so horrifying. It hurts him to know that he has inflicted it upon someone, someone able to understand it.–A.W. Strouse, in reference to the recent performance of Jarrod Kentrell at Ps1‘s “The Meeting”

I first heard Diamanda Galás’s The Plague Mass (1991) around 1994, when I would have been about 20 years old. Equal parts mass and babble, The Plague Mass is an elegiac tribute to Galás’s brother and other victims of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, a sonic rage against the silence surrounding the disease that redefines “the elegy” in the process. I suppose that I should make a confession here and say that contracting HIV was one of my biggest fears at the time. I was fresh out of the closet and ready to experiment, yet the media coverage of the crisis had pretty much told me that, as a gay man, an active sex life was a death sentence, a message I had been receiving since I was in fourth grade. There was something in Galás’s record to which I automatically, deeply connected. Although this brand of desire was new to me, there was also something deeply familiar about it–ancient even–and this feeling was produced by the horror of her work, not in spite of it.

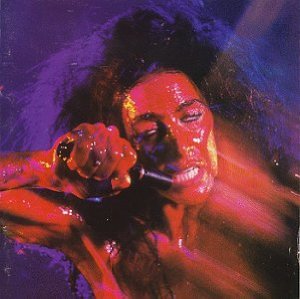

Cover of The Plague Mass (1991)

Recorded live in 1990 at Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City, The Plague Mass was conceived as a performance piece, enabling Galás to use sound to move in a messy, unstructured, and often terrifying way across multi-dimensional space. Her sonic trajectories seemed to take my global, abstract fears and make them intimate and concrete. In “Diamanda Galás: Defining the Space In-between,” Julia Meier describes Galás’s soundscape as composed of “chants, shrieks, gurgles, hisses often at extreme volumes, frequently distorted electronically and accompanied by a torrent of words” which defy description (2). In the space created by this cacophony, Galás mourns her brother, responding to the silence surrounding AIDS by making use of what composer and sound theorist Yvon Bonenfant refers to as “queer timbres” in “Queer Listening to Queer Vocal Timbres,” the unique, dynamic sounds of desire and self in the voice that also operate as a kind of touch, a reaching out to other desired and desiring bodies. In homage to Antonin Artaud’s theory of the theater of cruelty–in which audiences are exposed through multisensory domains to truths they often do not wish to see–Galás uses queer timbres to form an outsized means of aural communication in The Plague Mass that fills more affective space than standard musical productions or theater productions. The shrieks and howls suggest Galas as depicted on the album’s cover: flayed, raw, and radically open to the passage of every vibration. By erasing semantic and syntactical codes, these sounds deeply engage the entire body in the process of making sound.

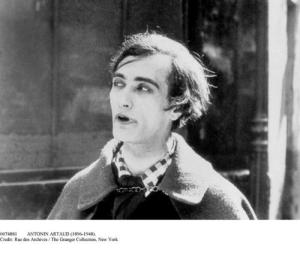

Artaud

Queering the traditional theater, Artaud argued for new intersensuality that would occupy space in a three-dimensional manner. In The Theater and Its Double, Artaud describes how the “intensities of colors, lights, or sounds, which utilize vibration, tremors, repetition, whether of a musical rhythm or a spoken phrase, special tones or a general diffusion of light, can obtain their full effect only by dissonances. But instead of limiting these dissonances to a single sense, we shall cause them to overlap from one sense to the other” (125). Texturing sound, or working with dissonance and disruption to create a more forceful product, offered Artaud a unique play between the senses, allowing it a more direct and apparent physical impact upon the bodies of both performers and the audience.

The plague and how it inhabits and destroys bodies is a central metaphor for sound and language in the work of both Artaud and Galás. Artaud focused much of his theory on the plague as an example not only of an affective space but also as a transformative event in human history and in individual lives. Artaud’s writing on the plague, however, also garnered him harsh criticism. By suggesting a theater in which language became subordinate to the shriek, the grunt or other non-semantic orality, he decried all of traditional French theater and its lofty legacy. Nonetheless, he was invited to speak about his essay “The Theater and the Plague” at the Sorbonne. Deciding to actually incorporate his ideas about ‘liquefying boundaries,” he began speaking in a standard oratorical mode but slowly devolved into a theatrical performance of the plague, eventually ending in shrieks of physical pain. In Watchfiends & Rack Screams, Clayton Eshleman describes how, by the end of his speech, the only people left in the lecture hall were a minor contingent of his close friends, including Anais Nin, who recounted the tale (12). The shrieks, the howls are all a further way to engage the whole body in the process of making sound, while also erasing semantic and syntactical code. In Gilles Deleuze’s estimation of Artaud’s work in The Logic of Sense, it reached the depths of language: “The word no longer expresses an attribute of the state of affairs; its fragments merge with unbearable sonorous qualities, invade the body where they form a mixture and a new state of affairs… In this passion, a pure language-affect is substituted for the effect of language” (89).

Jaap Blonk performs Artaud’s “To Have Done with the Judgement of God”

Reflecting and refracting Artaud, Galás uses the space of The Plague Mass to re-consider and re-theorize the ailing body. In her work the body represents not just Galás herself, but also the bodies of all the afflicted, the bodies issuing negation of suffering, and finally, the collective body of the spectacle of the AIDS crisis. Like Artaud, Galás sees the plague of AIDS as transformative, but without the safe buffer provided by the critical space of history. This plague is instead an immediate issue made all the more volatile due to the refusal to help the victims by the conservative Reagan administration as well as the rigidity of the Catholic Church’s encoded dogma that characterizes homosexuality as sinful depravity and refuses to acknowledge the need for AIDS education and condom distribution. Galás evidences this in the opening track “There Are No More Tickets to the Funeral” which incorporates traditional Christian hymns, liturgical representations of condemnation, and the voices of the afflicted.

These appropriated sounds circulate in constant tension, queering the ominous, authoritative patriarchal drones by contrasting them to the timbres of desire and pain embodied by the shrieks. In “Confessional (Give Me Sodomy or Give Me Death),” the narrator’s voice bleeds into the frantic voice of the defiant dying, blending in with the conjured voices of angels of death that hover over the bed. This commentary places the listener in a very immediate and uncomfortable multidimensional space encompassing several terrifying aspects of death. Here Galás exemplefies Bonenfant’s queer timbres through the tactile effect of layered sound that is felt with the skin, in the bones, as well as with the ears, communicating a palpable experience that lies beyond the barely-nuanced music it is seductively easy to grow accustomed to.

It is Galás’s use of sound’s affective properties that makes The Plague Mass most effective as queered communication. In “This is the Law of the Plague” she incorporates elements of glossolalia, colloquially known in religious communities as “speaking in tongues,” a speech act that embodies voice by implying a physical loss of control of the body as well as the casting off of concrete linguistic structure. Galás’s use of glossolalia deliberately blurs the border between spiritual possession and the madness inherent to AIDS as the virus passed through the blood/brain barrier of its human host.

Aided by electronics, Galás’s vocals begin as the chant of orator. Punctuated by a throbbing, sparse single drum-beat, her sickened, keening crawl of words enumerates in detail what it is that defines a person as unclean. The language is precisely enunciated, each word sharply edged and cornered—a practice that would no doubt double Artaud over in pain, given his struggle with schizophrenia that left him vulnerable to crisp sounds. Slowly, Galás’s voice rises to the shriek of a pious, avenging angel, a shrill, wail shimmering with vibrato communicating the sound of a raptured body, rent in chaotic ecstasy. Eventually her ululations are submerged in a bath of primordial babble, a place where language moves in every direction through a body somehow more permeable, a sonic space that Deleuze would describe as topographic, that is, possessing heights and depths. Enacting and inviting the babble of the mad and the afflicted maintains a red line on the tolerance of the listener’s psyche before returning, without ceremony, to the sparse and cold incantations of the church. Here queer(ed) timbres push the audience to limits well past the reaches of patriarchal or accepted sound; Galas plays along the edge of tolerance before dropping the audience abruptly back into the decidedly colder and less humane sonic tropes of an unforgiving religion.

Galás’s sonic practices encourage in me a listening that reaches out into space to connect with these sounds, whose physicality communicates fears and apprehensions that are old enough to feel genetically encoded in my psyche. Bonenfant describes this reaching as “queer listening,” an extrinsic process based on desire in which “we listen ‘out’ for (reaching towards) voices that we think will gratify us” (77). Bonenfant queers the body in the process of sound; it becomes abstracted, absorbed into a process and functioning on many layers that include—but also subsume—the subjective Cartesian body of agency we are comfortable with. The body becomes bodies, and it becomes present in spaces that go beyond the immediate space it occupies in space/time. Galas traverses time and space in The Plague Mass, from the ancient litanies of hymns and spirituals to the anguish of those afflicted with AIDS, and layers voice on voice until they are inextricable, a huge din telling more than just a story, or The Story but the stories of many.

Image by Flickr User 1v0

In a personal e-mail exchange, Bonenfant clarified his relation to both Artaud and Galás. When asked if he was influenced by Artaud he explained:

Not directly, but certainly indirectly, and his ideas affect extended voice practice generally. I think the idea of the ‘theatre of cruelty’ is often deeply misunderstood and it was a product of its time. I understand Artaud to have been crying out for an anti-bourgeois theatre that actually stirred people up. But stirring people up is only part of the story. What stirs some, attracts others. Now, my argument is more that: these voices we might call ‘queer’ stir SOME people up but actually they ATTRACT others – others who might be seeking queered bodies to contact.

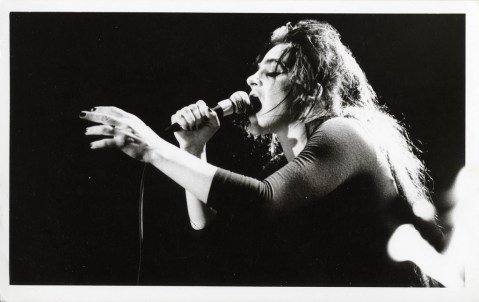

Bonenfant went on to explain that artists such as Galás can thus make contact with people who desire the kind of disruption or ‘stirring’ that they provide. He went on to relate a story that Galás shared in an interview, in which she described a performance in which she looked out at the audience and noticed a very young boy listening to her perform. For the rest of the concert, Galás said she felt guilty for the damage she was undoubtedly inflicting on the young boy’s ears and psyche. However, after the concert the boy approached her and thanked her profusely. It turns out that he had suffered from a terminal and painful illness and felt unable to express the physical and emotional distress that he lived with. Here, though, was an artist onstage articulating it, broadcasting it to him and others, for him and others. This is what Bonenfant refers to as “an affective, somatic bond” created through shared sonic experience, and this is what Galas constructs. By standard definitions The Plague Mass is almost unlistenable, but yet it has connected audiences remote in space and time (a nod here to Karen Tongson’s “remote intimacy”). A sonic reaching out attracting listeners similarly reaching, its indelicate music draws the suffering near, providing a form of collective comfort by exploring and embodying the suffering, grief, and rage located beyond the permeable membrane of conscious thought and feeling.

Diamanda Galas performing in the 1980s, Image Courtesy of Flickr User Carl Guderian

It is this kind of connection through a tonal richness that is uncoded but yet full of information that is radically important. Galás’s groans, growls, and chants create an intersubjective circuit of communication that moves active listening outside of the body and draws visceral connections in a three-dimensional psychic space. This is what Galás immediately stirred in me back in 1994, and what I have been determined to recover and communicate since that first listening cut me to the quick. Queer listening does not just entail an affirmation of the soundtracks of queer lives–a kind of perpetual disco, 12” remix project–but rather it also demands a critical–and visceral–vulnerability to the jarring, violent world arranged against queer agency. Galas’s work hijacks the elegy and queers it, extending it to us as an offering against the true horror: the official silence in the face of so much death.

—

Featured Image of Diamanda Galás courtesy of Flickr user digital_freak

—

A Taurus who enjoys the ocean, Airek Beauchamp is currently at SUNY Binghamton pursuing his PhD in Creative Writing. He also studies composition pedagogy and queer theory, although he is becoming more and more seduced by sound studies. He can rock a disco all night or just stay in and maybe catch up on some 30 Rock. Some call him fancy, some call him a bitch, but really he is both. He is a multiplicity of multiplicities, all in one mortal shell.

Blinded By the Sound: Marvel’s Dazzler – Light & Sound in Comics

Trying to reproduce the popularity of KISS-themed comics: Marvel Super Special #5 (1978)

I recently got my hands on a complete set of Marvel Comics’ Dazzler, a comic from the early to mid-80s that featured Alison Blaire, a mutant with the power to transform sound into light. She was the result of an attempted collaboration between Marvel and Casablanca Records. The idea was that rather than publish a comic based on a pre-existing musical act (as they had in 1977 with KISS), Marvel would create a character and Casablanca would, in the words of one of the co-creators, “create someone to take on the persona,” with the potential for a movie tie-in. Casablanca dropped the project before the first issue of the comic, but Marvel re-tooled the character and went ahead with the Dazzler—a talented, yet struggling singer stuck playing at cheesy discos and small clubs while dreaming of wider success.

The last time I wrote about sound in comics, I mentioned how despite (or because of) sound’s transparency, it is an unobstrusive tool in providing the cues needed by readers to provide the closure through which comic literacy functions. The Dazzler series is not a great comic, it is often schmaltzy, repetitive and rife with errors, and just when it started to fulfill a bit of its promise, its creative team and the comic’s direction were changed and it was canceled soon after, but despite this, it is the perfect subject for looking at the representation of sound in comics. Dazzler’s power literally shines a light on how pervasive imagined sound is in this visual/textual form. It also makes room for even more sounds to be woven into the title’s narrative. Since Alison Blaire is an aspiring singer the most prevalent sound present in this title—less common in other popular super heroes titles—is music. Dan Fingeroth and Jacob Springer (who wrote the majority of Dazzler’s brief run) had many opportunities to depict a visual representation of singing.

from Dazzler #21 (Nov 1982). By Fingeroth & Springer

The fans react to Dazzler’s singing – from Dazzler #7 (August 1981), by DeFalco, Fingeroth & Springer

As a singer, Dazzler is a maker of sounds in addition to a user of the sound already present throughout the medium. As a result, in addition to the visual representation of sound through Dazzler’s glowing light show, the writers were in a position of having to use text to describe the quality of sound more often than usual for their genre. As Tom DeFalco (a co-creator and sometimes writer on the series) said in a 1980 interview with Comics Feature, “I have to put in a lot of sounds in the captions and that I hope that kids who very rarely read captions will read these so they’ll know where the sound is coming from. But the good thing about sound is that you are always surrounded by sound.” DeFalco’s answer illustrates the contradiction at the heart of comic sound—it may be ever-present, but because of this is taken for granted to such a degree that he worries that its source will not be self-evident on the comics page. He adds that one way around this, because of Dazzler‘s focus on music, is through descriptions of the audience’s reactions to it—how it makes them feel is a way to clue the readers into the source and quality of sound present in the panels.

It is the affective relationship to sound that marks Dazzler as very different from other superhero comics. All the super-villain battles and fear of the revelation of her mutant powers are merely the narrative obstacles to her primary goal and obsession—singing. In order for that work, the emotions that emerge from her performance (both for Alison and those listening) needs to be evoked (something that the comics unevenly succeeds at). The colorful lights that are often part of a stage show are, in her case, a direct result of her relationship to not only hearing/absorbing sound, but making sound. She repeatedly explains that rhythmic nature of popular music makes her powers easier to use, because she can feel its pulse. For Alison Blaire, hearing, making and using sounds are conflated by means of the visual and textual, allowing the reader to see what he cannot hear or feel. In other words, Dazzler’s conceit is most successful when it evokes an empathic connection between the reader and the imagined sounds.

Black Bolt’s scream converted into light – From Dazzler #19 (Sept 1982), by Fingeroth & Springer

The feeling around sound can also be evoked through its absence. A common practice in mainstream superhero comics is the guest appearance by a popular hero in a new or poorly-selling comic in order to boost sales, and Dazzler seemed to have cameo by some better known character almost every issue. This practice allowed for writers and artists to depict what had for decades been undepictable. When Dazzler teams up with Black Bolt, King of the Inhumans (a Fantastic Four character from back in the Kirby days) he is finally allowed an opportunity to use his greatest and most feared power, his voice. Black Bolt is forever silent. His voice is so powerful a weapon that even his whisper can inadvertently kill all those around him. Thus, despite being an iconic Silver Age character, the voice of Black Bolt is one that can never be “heard” by comic readers. His silence is part of his identity and grants him a tragic and noble-bearing. As such, when he is teamed up with Dazzler, her power becomes the perfect vehicle for representing the unrepresentable sound—Dazzler absorbs the sound of his voice to emit the energy needed to defeat the super-villain. In having the characters work together, the writer was able to use one character’s power to finally represent the other’s. In this moment there is a sense of relief and emotional release, along with a sense of peril that bound to Black Bolt’s voice gives the unheard sound resonance.

Allison turns up the muzak to power her ability. From Dazzler #8 (Oct 1981) by DeFalco, Fingeroth, Springer & Coletta

As the title continued (and after its cancellation, when Dazzler became a member of the X-Men), Alison Blaire’s powers developed in different ways, the most fascinating was the development of her hearing. While early in the character’s career she was dependent on passive hearing, often carrying a portable radio with her in order to insure she had sufficient sound with which to use her light powers, later she developed acute active listening skills. As this aspect of her power developed, it became clear that it was not necessarily the force of sounds themselves that determined the extent of her power (though clearly loud sounds could be more easily transformed into more powerful forms of light, like ultra-focused lasers), but her attentive listening. The more attention she could pay to sounds and could discern even faint sounds, the more she could absorb and transform—later she is even able to use the sounds of digging insects and worms to save herself when she is accidentally buried alive.

From Dazzler #1 (March 1981) by DeFalco & Romita, Jr.

By the end of her original series, Dazzler‘s new writing team had her mostly abandon her musical ambitions and take the more common (and dare I say, more boring) comic book route of getting a costume and joining a team of liked-minded super-beings. Because of this, the character’s special relationship to sound is lost in the shuffle of convoluted continuities and cosmic crises present in the various X-titles. There is less time and attention paid to song and sound as power and its emotional weight. The abandonment of her career goals also abandons the opportunity to explore a unique representation of sound and identity in a medium where identity is writ large. However, if there is a take-away from the strange, mostly failed, collaborative experiment between comics company and records company, it is that like Alison Blaire, if the comics reader “listens” carefully to the sounds present in the text and pictures there is a potential for a lot more depth and appreciation of how sound’s depiction is crucial to comics’ formal success.

—

Osvaldo Oyola is a regular contributor to Sounding Out! and ABD in English at Binghamton University.

Recent Comments