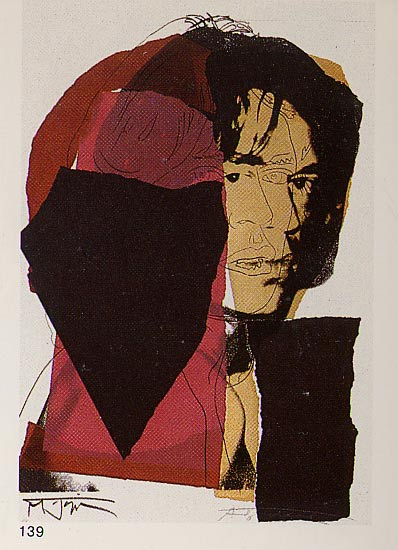

Sound + Vision: Andy’s Mick

Andy Warhol – Mick Jagger 1975, Image by Flickr User Oddsock

Hello Internet! It’s great to be here in cyberspace! Are you ready to rock? Today’s dispatch from our Spring Series, Live from the SHC, finds Cornell’s Society for the Humanities Fellow Eric Lott jamming it out on the relationship between the early 70s sound and vision of one Sir Mick Jagger. If you happen to be thinking that Monday morning at 9:00 a.m. is the least rock and roll time slot possible, just remember that’s when Jimi Hendrix gave “The Star Spangled Banner” the business at Woodstock. To give earlier installments by Damien Keane, Tom McEnaney, and Jonathan Skinner a listen, click here. As May comes to a close and the “Sound: Culture, Theory, Practice, Politics” fellows reluctantly break up the A.D. White House house band, look for our final two dispatches from Jeanette Jouili and Society Director Tim Murray. Until then, we’ll keep turning it up to 11 here at Sounding Out! –JSA, Editor in Chief (and 2011-2012 SHC Fellow)

Hello Internet! It’s great to be here in cyberspace! Are you ready to rock? Today’s dispatch from our Spring Series, Live from the SHC, finds Cornell’s Society for the Humanities Fellow Eric Lott jamming it out on the relationship between the early 70s sound and vision of one Sir Mick Jagger. If you happen to be thinking that Monday morning at 9:00 a.m. is the least rock and roll time slot possible, just remember that’s when Jimi Hendrix gave “The Star Spangled Banner” the business at Woodstock. To give earlier installments by Damien Keane, Tom McEnaney, and Jonathan Skinner a listen, click here. As May comes to a close and the “Sound: Culture, Theory, Practice, Politics” fellows reluctantly break up the A.D. White House house band, look for our final two dispatches from Jeanette Jouili and Society Director Tim Murray. Until then, we’ll keep turning it up to 11 here at Sounding Out! –JSA, Editor in Chief (and 2011-2012 SHC Fellow)

—

After we left the Carlyle I told Jerry I thought Mick had ruined the Love You Live cover I did for them by writing all over it—it’s his handwriting, and he wrote so big. The kids who buy the album would have a good piece of art if he hadn’t spoiled it. –Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol’s complaint in his Diaries captures the almost cartoonish play for artistic control between himself and Jagger in the 1970s—between painter and singer, portrait artist and subject (Jagger and the other Stones biting each other), the visual and the verbal (“he wrote so big”!): between sight and sound in the realm of popular music. Warhol was no stranger to sound artistry, of course, from his work with the Velvet Underground to the everyday taping he did with his portable cassette recorder, the machine he called his “wife.” But Warhol as visual conceptualist returns us to a moment when, through album art and other commercial iconography, the visual domain shaped our sonic experiences perhaps more immediately than it does in these digital days. At the recent EMP conference in New York, I raised the question of the visual/conceptual from the perspective of sound, looking and listening to how the modalities were conjoined during an excellent and rather brief (and nowadays mostly scorned) passage of Jagger time in the middle 1970s: Jagger in his thirties.

Andy Warhol designed cover for Sticky Fingers (1971)

A funny thing happened after Exile on Main St. in the early 1970s: the Rolling Stones became a New York band instead of a London and L.A.-based one, and their frontman Mick Jagger, always an outlandish presence, became a swishier one. The manner in which this happened owes a lot to their encounter with Andy Warhol. From his cover designs for Sticky Fingers (1971) and Love You Live (1977) to the Stones’ renting of his Montauk house to rehearse for their 1975 tour to conspicuous late-70s hanging out together at Studio 54 and New York dinner parties of the rich and not so fabulous, it’s clear the Stones, or at least Jagger (and for sure his wives, Bianca and Jerry Hall), steered ever closer to Warhol’s orbit.

Good writing about the Stones’ New York phase has recently begun to appear, including Cyrus Patel’s 33 1/3 book on Some Girls (2011) and Anthony DeCurtis’s liner notes to that record’s 2011 deluxe re-release; Ron Wood’s Ronnie: The Autobiography (2008) opens with the band’s famous promo stunt playing on the back of a flatbed truck rolling down lower Fifth Avenue on 1 May 1975 to advertise their upcoming tour.

.

But the influence on them of the Andy aesthetic has gotten far less attention, at least in pop music criticism (the Warhol Museum mounted a show, Starfucker: Andy Warhol and the Rolling Stones, in 2005, full of great stuff). In particular, Warhol’s 1975 Ladies and Gentlemen black drag queen series, and the draggy portrait series of Jagger done at the same time and in the same way, attest to their mutual influence on each other. The gain for the Stones was exponential: a new persona for a new decade and indeed a new town.

Andy’s Mick, Image by Flickr User Shreveport Bossier

The persona as influenced by Warhol arrives at the nexus of drag, hustling, and stardom, and Jagger in the 70s can be seen to be addressing and/or capitalizing on all three. Warhol’s Ladies and Gentlemen was originally referred to as simply the Drag Queen series. As Bob Colacello tells the story in Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up, some Factory workers were sent to the Times Square gay bar The Gilded Grape to hire several hustlers there to sit for some Warhol Polaroids for fifty dollars a pop. (They later quipped that they were used to doing a lot more than that for fifty bucks.) As was his practice at the time, Warhol transferred these images to silkscreen for mechanical reproduction, over (or under) which he painted in unusually expressive fashion, at times applying collages of torn paper as well. Geometries of color in these pictures war with the photographic image; they signify on race as well as the drag queen’s everyday glamour and its defensive-aggressive thrust-and-parry. In any case, Times Square hustlers of color became stars in Andy’s hands. At this point the title was changed to Ladies and Gentlemen—perfect, since his subjects in the works can be thought of as both—and it may be that the title was taken from the 1974 Stones film of their celebrated 1972 tour, Ladies and Gentlemen, the Rolling Stones (it’s worth recalling lest we be tempted to discount such a film that almost everyone in a broad swath of the New York milieu saw it—in Just Kids (2010), for example, Patti Smith writes of seeing the film with Lenny Kaye and then going off to CBGB to catch a set by Television). What is certain is that Warhol at this same moment was giving Polaroids he had taken of Jagger in Montauk the exact treatment he gives the drag queens in Ladies and Gentlemen.

Andy Warhol’s Mick, 1975, Image by Flickr User Thomas Duchnicki

Being a drag queen is really hard work, Warhol famously wrote in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (1975), and it is in part the connections between hard work, its celebrity remuneration, drag, and prostitution that link the Ladies and Gentlemen series with the portraits—paintings and then prints—of Jagger. These connections link this output with Warhol himself, making the portraits a sort of displaced self-portraiture. Their mechanics, if you will, seem homologous with drag, in fact. Starting with the Warhol-snapped Polaroid—not, say, with newspaper photos or commercial iconography as in Warhol’s 60s silkscreens—the works depend on Warhol’s presence, which then puts the images through the silkscreening process, after which (or before it) an uncharacteristically painterly (or collagist) procedure is applied, the latter akin to make-up itself. Where in some of the series the paint obscures the face, acting as a kind of negation or comment on the negation behind black queer hustling, in most of it the faces rise to a new form of presence or fabulousness, as if by repeating the act of drag the portraits affirm its “success.” Warhol’s make-over of Jagger, meanwhile, both drags the singer and makes him Warhol’s: Andy’s Mick.

According to a scheme worked out by Warhol and Jagger, the latter signed the portraits so that they could promote both artists. Which, if it doesn’t exactly make Jagger a co-author of the works, does signal his endorsement of Warhol’s vision of him. (Indeed the Warhol Museum has a facsimile of a 1983 letter from Jagger to Warhol asking for his assistance with Mick’s autobiography—a collaboration that boggles the mind.) As John Ashbery had it in Self-Portrait In a Convex Mirror, his multiple-prize-winning long poem of 1975:

Your [the artist Parmigianino’s] eyes proclaim

That everything is surface. The surface is what’s there

And nothing can exist except what’s there;

It [the surface] is not

Superficial but a visible core. . .

Your [Parmigianino’s] gesture . . . is neither embrace nor warning

But . . . holds something of both in pure

Affirmation that doesn’t affirm anything.

Not a bad definition of the Warholian image, this, and in the 1970s, as the Rolling Stones entered their second decade of performance and stardom, Jagger took the lesson and ran with it. A new self-consciousness about his own stardom enters Jagger’s (underrated) lyrics in the 70s; while self-reference is not unknown in the band’s 60s work (cf. 1968’s “Street Fighting Man”), and while one of their first hits takes on the culture industry itself (“Satisfaction”), in the 70s a new kind of meditation on rock-star celebrity enters the picture—I have seen the culture industry, and it is me: Jagger begins to write about himself as the culture industry. And this under the sign of Warhol, I think, which is to say, with a queerly knowing intimacy informed by a sense of the artist-star as a hustler for money in what we might call image-drag. Everything is surface, the surface is what’s there and nothing can exist except what’s there, and it’s not superficial but a visible core.

From 1973 forward, in the music from Goat’s Head Soup to Tattoo You (with It’s Only Rock n Roll, Black and Blue, Some Girls, and Emotional Rescue in between), and even more on the covers of these albums, culminating in the one for Some Girls with the Stones in drag—Andy in the Warhol Diaries: “[Mick] showed me their new album and the cover looked good, pull-out, die-cut, but they were back in drag again! Isn’t that something?”; the Some Girls cover, though Warhol didn’t do it, really does recall his drag queens, right down to the double drag of the inner-sleeve pull-out—to say nothing of the made-up glam of the 1975 and 1978 tour performances: in all this one sees a flouncier, queerer Mick, one that Jagger nodded to in various lyrics (for that demonstration you’ll have to wait for the longer version of this piece!). What this means in part is that the cliche we have of Jagger strutting like a neo-blackface soul man is due for revision: it’s much more precise to think of his aura as proximate to black femininity (icons like Tina Turner, say, who of course opened for the Stones), which he (re-)crafted through the adoption of a persona right out of Warhol’s colored drag queen sensibility.

.

So why the now-canonical assumption of the Stones’ decline at just this moment? Is their 70s sound discounted because of the queer reinvigoration of their visual/conceptual appeal? (One counter to this hegemony is Ellen Willis’s fine 1974 review of It’s Only Rock n Roll, included in her Out of the Vinyl Deeps.) Did the Stones’ sound change all that much, beyond new acquisitions of this reggae vibe or that funk riff or the other disco groove, or does the insistence on their fall come from a sense of their queening around? Is it this—not only this, I know, I know, Mick’s such an asshole, but still—that lies in part behind the (particularly post-Life) cult of Keith?

—

Eric Lott teaches American Studies at the University of Virginia. He has written and lectured widely on the politics of U.S. cultural history, and his work has appeared in a range of periodicals including The Village Voice, The Nation, New York Newsday, The Chronicle of Higher Ed, Transition, Social Text, African American Review, PMLA, Representations, American Literary History, and American Quarterly. He is the author of the award-winning Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (Oxford UP, 1993), from which Bob Dylan took the title for his 2001 album “Love and Theft.” Lott is also the author of The Disappearing Liberal Intellectual (Basic Books, 2006). He is currently finishing a study of race and culture in the twentieth century entitled Tangled Up in Blue: The Cultural Contradictions of American Racism. This post is adapted from a talk Eric gave at the 2012 EMP POP Conference in New York City entitled “Andy’s Mick: Warhol Builds a Better Jagger.”

Pushing Play: What Makes the Portable Cassette Recorder Interesting?

One of my earliest memories of sound recording is one of my earliest memories, period: an isolated image of my own index and middle finger trying to push down the “record” and “play” buttons on my father’s portable cassette tape recorder. More prominent than the visual element of this memory is the haptic one: I can still call up the sensation of the effort required to make the red button go down and latch and the stress on the top joint of my index finger as the resistance bent it backward. Also still with me is a trace sense of the threat of sharp pain, as if at some point previous I had been wounded (perhaps pinched?) by these buttons. How young must I have been to have experienced this degree of opposition from such a small, unassuming device? And whence this desire to persist in the face of it?And: how and where does this object–so unprepossessing with its five big buttons, volume slider, cartridge tray, and little speaker–fit into sound studies and the history of sound recording technology?

There’s a small, rich, growing body of work on tape recording–including work by scholars as different as Kathleen Hayles, Steven Connor, Michael Davidson, and this blog’s doyen, Jennifer Stoever-Ackerman–but almost invariably it focuses on the reel-to-reel recorder, the device the cassette recorder was meant to simplify and miniaturize, at the expense of sound quality. The reel-to-reel was a vital contributor to the development of stereo and hi-fi hobbyism; it was also the mechanism at the center of a series of bold modernist literary experiments with tape recording by Samuel Beckett, William S. Burroughs, David Antin, and others.

Aside from Andy Warhol’s use of it to tape huge swaths of his everyday life (in 1965, he “wrote” a novel consisting of 24 largely consecutive hours of transcribed cassettes) the cassette recorder has no such avant-garde pedigree. The name of the first model, the Norelco Carry-Corder 150, which appeared in 1963, shows the primary focus of its manufacturers’ vision. Ads and trade journal articles from around this time touted the ease with which the device could be toted around on a vacation with the aim of producing an “audio album” of the trip. Doubtless, such albums were made and some may even still exist. But I suspect that the most vibrant history of the Carry-Corder and its descendants lies in the device’s easy adapability into the play world of children. As I and many others of my generation remember it, the pleasure of playing with the device was the way it instigated various sorts of performance, usually based in mimicry of ones we’d consumed through other electronic media. In a manner not unlike Warhol, we created our own little media empires: Dj-ing, news announcing, sportscasting, hosting talk shows with the baby and the dog as guests, singing like Cher on TV, re-enacting TV comedy sketches, recording one’s own comedy sketches, and on and on.

It’s not obvious how sound figures in the context of children’s play. Certainly, the quality with which the tape recorder recorded and played back sound mattered little, if at all. What mattered was the way the device initiated and constructed scenes, provided roles to play. Analogously, as David E. James has noted, one of the most powerful aspects of Warhol’s practice of bringing his Carry-Corder 150 everywhere he went (he was an early adopter, purchasing one in 1964) was that it “ma(de) performance inevitable” and “constitute(d) being as performance” (Allegories of Cinema, page 69). Even playback itself was a matter of secondary interest; how many times do you think I listened to the tape of myself “broadcasting” two innings of a random mid-70s Mets game, delivered as I watched on TV with the sound turned down? My wager is on none. Still, sound is the raison d’etre of the cassette recorder. A few years later, kids might have done similar things with a video camera, but to a lot of kids, the early mass-marketed versions of that device felt much more formal, complicated, authoritative. That was the instrument through which the “official” history of the family was to be told; the tape recorder picked up the creative fragments, the bored interstices, the embarrassments, the extremes–parts of a world that wasn’t to appear before guests. Plus, the sound-based device actually offered greater reach and flexibility along with more forms of integration into other media like television.

My early memory of the recorder, however, seems more primal. Given its intensity, it seems clear that the tape recorder served as a vehicle toward several important forms of self-demarcation, helping me to discover and negotiate certain limits: of my body, of my agency vis-à-vis machines, of my relationships to my parents, of my family’s position in a larger social and economic world. (And in fact, the device was an important part of my family’s livelihood, vital to my father’s work as a radio reporter.) In retrospect, I seem almost impossibly young to be left to my own devices with the machine, and I also have a vague sense that I had been violating some prohibition, perhaps a decree that the recorder is “not a toy.” I wonder how much the force of such a decree originated precisely in the ease with which it could and did become a toy.

It’s unlikely that Friedrich Kittler was going to list “cassette tape recorder” next in his book title after “gramophone, film, and typewriter.” It’s unlikely he had an image of the device in mind when he wrote his bravura dictum, “media determine our situation.” Some technologies don’t stand up to such sweeping statements, toward which media studies sometimes seems particularly drawn. Certain devices, I think, necessitate a broadened and diversified understanding of the things both sound and technology do—even things that aren’t “about” sound in a conventional sense. For many historical narratives of sound reproduction, the cassette tape recorder is a regressive device, a drag on the pursuit of greater audio fidelity, with fidelity defined as “presence.” But the qualities of the cassette recorder that make it significant to our field are manifold, and some of them will be qualities that arise out of their adjacency to the central fact of recording and playing back sound. The “forgotten” areas of the history of sound reproduction technologies aren’t the notable failures—the 8-track players, which after all still draw camp-retro interest–but the most mundane successes. The portable cassette tape recorded never truly failed, it just got left back.

—

Gustavus Stadler teaches English and American Studies at Haverford College. He is the author of Troubling Minds: The Cultural Politics of Genius in the U. S.1840-1890 (U of Minn Press, 2006) and co-editor (with Karen Tongson) of the Journal of Popular Music Studies. His 2010 edited special issue of Social Text on “The Politics of Recorded Sound” was recently named a finalist for a prize in the category of “General History” by the Association of Recorded Sound Collections. He is currently working on Andy Warhol’s sound world, Woody Guthrie’s sexuality, and other stuff.

Recent Comments