Sonic Contact Zones: An Interview with DJs MALT and Eat Paint in Koreatown, Los Angeles

On Sunday, February 21, Atlanta-based hip-hop photographer Gunner Stahl will be DJing at a raw space being built at 4317 Beverly Boulevard in Los Angeles’ Koreatown as part of the Red Bull Music Festival. Red Bull suggests that many of the photographer’s artistic subjects, such as Tyler the Creator, Playboi Carti, Lil Uzi Vert, Gucci Mane, and/or The Weeknd might make guest appearances during his set. This star-studded stage with financial backing from the drink that gives you wings will stand across the street from Vilma’s Thrift Store, DolEx Dollar Express, Gina’s Beauty Salon, and Botanica Y Joyeria El Milagro. Tickets are a modest $15. At first glance, the location choice might seem odd; why not the legendary Wiltern Theater just down the street on Western? Or why not set up a stage inside MacArthur Park? Those are definitely options, and many performers do grace the stage of The Wiltern for fans in Koreatown and the greater Los Angeles area. However, for those who know Los Angeles’ Koreatown gets down, discounted snacks and pedicures a stone skip away from millionaires sounds just about right.

Figuring out these connections between sound, capital, culture, ethnicity, and art in LA’s Koreatown has been a popular pursuit in recent years. The year was 2014. The place was The Park Plaza Hotel on the outskirts of Los Angeles’ Koreatown. The people performing were TOKiMONSTA (Jennifer Lee), Far East Movement (Kevin Nishimura, James Roh, Jae Choung, and Virman Coquia), Dumbfoundead (Jonathan Park), and others. The reporter was Erik Kristman for Vice Media’s Thump. In the article titled “SPAM N EGGS Festival Was a Window to LA’s Multiculturalist Underground Movement,” Kristman proclaims: “Koreatown’s spectrum of sound, a culture hidden beneath its mid-Wilshire scenery, is no doubt one of the few remaining jewels of the LA underground.”

In Club Cultures: Music, Media, and Subcultural Capital (1996), Sarah Thornton writes that DJs “play a key role in the enculturation of records for dancing, sometimes as an artist but always as a representative and respondent to the crowd. By orchestrating the event and anchoring the music in a particular place, the DJ became a guarantor of subcultural authenticity” (60). Asian American DJs performed in Koreatown, so the electronic music and hip hop they mixed was enculturated not only with a Los Angeles neighborhood flair but also with an ethnic twist.

Park Plaza Hotel, Taken by Flickr User Cathy Cole (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Park Plaza Hotel, now The MacArthur, has its own important history as a venue as well. Built in the 1920s by prominent Los Angeles-based architect Claud Beelman, the building has hosted the racially exclusive Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, night clubs such as Power Tools with attendees such as Andy Warhol, and has been a site of numerous films and music videos such as Kendrick Lamar’s “Humble” (2017). It survived the demolishing of similar Art Deco buildings during the 1980s. It survived the 1992 Los Angeles riots following the acquittal of four police officers who beat Rodney King and the killing of 15-year-old Latasha Harlins by Soon Ja Du, the Korean-born convenience store owner of Empire Liquor on 91st Street and Figueroa Avenue. It survived, if not flourished, in the subsequent gentrification of the Wilshire Center area with eager real estate agents and endowed buyers who are made nostalgic by the building’s Art Deco façade. The right DJs playing in a prime spot such as The MacArthur could definitely guarantee a level of Los Angeles subcultural authenticity for attendees. But what kind of authentic? And was that something anyone was trying to go for?

Kristman’s caricaturization of Koreatown certainly reveals how this visage of authenticity affected him. In his words, Koreatown is a diamond waiting to be mined. Koreatown is hidden. Koreatown’s “spectrum of sound” takes the singular verb “is,” meaning it functions as a unified, indistinguishable whole. Kristman has “no doubt” about his analysis of his authentic trip to Koreatown.

The openers of Spam N Eggs that night were two techno DJs and producers named MALT (Andrew Seo) and Eat Paint (Vince Fierro). Together, they run the Los Angeles-based Leisure Sports Records. We met at the Seoul-based coffeehouse Caffé Bene in Los Angeles to share misugaru lattes and talk about Kristman’s statement.

“I definitely wouldn’t call ‘Koreatown’ very underground,” says Vince. “It’s certainly become a new social center to LA’s night life, and there was a time when there was a feeling of great potential for a solid underground movement. But sadly, there have not been any significantly artistic home-grown breakthroughs coming from K-Town.”

Vince continues: “Rather, it serves as a new landing pad for the very commercialized Korean hip-hop and EDM cultures in Los Angeles. These genres dominate the K-Town club landscape. Unfortunately [pause] to me, anyway [pause] it’s success not won with any kind of daring artistry or underground legitimacy but rather with familiar aesthetics and neon lights.”

“[Los Angeles] helps them, too,” adds Andrew. “They’ll close off streets and bring in vendors because it gets people out spending money. A lot of the Korean stars come out for these events, but the thing is [pause] what kinds of people are these events attracting? Obviously, Koreans, or people that are fans of Korean music. I think Korean people here have a lot of pride, and they see that there is a rise in the culture and the area’s popularity and they’re jumping on that. They’re trying to make it bigger and better. If you walk around Koreatown, you’ll see gentrification happening everywhere.” He references the Wilshire Grand Center, the Hanjin Group-owned skyscraper that stands taller than any other west of the Mississippi, and its surroundings as evidence.

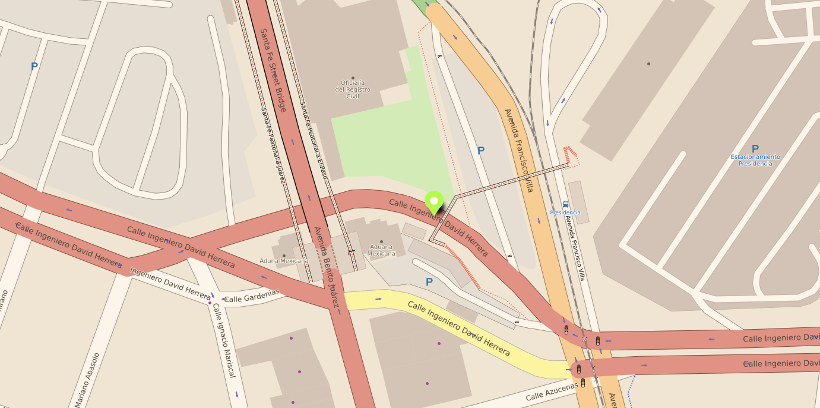

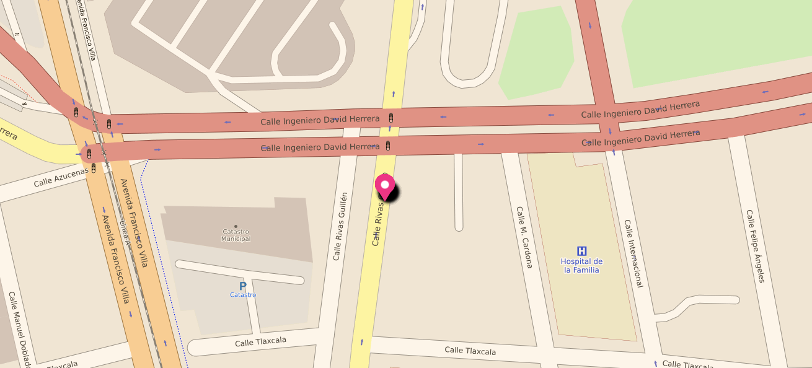

Urban studies carried out by Kyonghwan Park and Youngmin Lee, Kyeyoung Park and Jessica Kim, and others on Koreatown’s fraught relationship with surges of capital have made similar acknowledgments in wonderful detail. These surges are not evenly distributed among clubs; there are many more “secret” dimly-lit rave spots that pop up throughout the district than there are widely advertised above-ground clubs in Koreatown. Even relatively established clubs such as Union at 4067 West Pico Boulevard or Feria at 682 Irolo Street were not glamorous (and both have closed since the time this recent interview was conducted); they are surrounded by predatory lending offices and abandoned shops. Andrew gave me the address of an upcoming rave spot in Koreatown; it was basically under an apartment complex.

“I think they just want to bring what they build in Korea over here because that’s how they do it over there,” adds Andrew. “They just have apartments and then clubs and restaurants underneath or underground. It’s kind of like how Tokyo is.”

If this “hidden, underground” Koreatown culture does exist, as Kristman suggests, then finding it requires ignoring the flashing lights of Spam N Eggs and seeking out the darker warehouse raves. It also requires a level of suspended disbelief that Koreatown is untouched by hipster gentrification and instead an embracing of a subcultural essence that goes beyond city architecture and real estate. The physical space of sections of Koreatown might not be as important as the potential for the production of space in terms of creating sonic contact zones.

sign in Koreatown, Los Angeles by Flickr User vince Lammin (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The zones created by artists such as Malt and Eat Paint are mobile and fleeting as they pop up whenever and wherever these DJs perform. Like Josh Kun famously put forward in his book Audiotopia: Music, Race, and America (2005), the music these musicians produce and mix has the ability to create audiotopias “of cultural counter that may not be physical places but nevertheless exist in their own auditory some-where” (2-3). Electronic music, and perhaps similarly this “jewel-like” spectrum of Koreatown sound, has the ability to implant identity into the buildings and surrounding neighborhoods. What once was a Mexican restaurant and is now abandoned becomes a pulsating techno club attracting those Angelenos who shy away from the more commercial scenes.

Perhaps Kristman was focusing more on the Asian American DJs themselves than the types of music they were spinning or The Park Plaza Hotel and its situation in Koreatown. As Asian Americans, these DJs represent and are representative of an authentic subculture to which Kristman bears witness. However, many artists shy away from or sometimes outright deny any racial or ethnic connections being made between their art and their identities. Andrew and Vince shared personal and well-known examples of ambivalent attitudes toward such labeling. Jason Chung, also known as Nosaj Thing, is one of the best-booked electronic performers today, flying around the world sponsored by Adidas or playing huge shows with Flying Lotus. Vince, who worked very closely with Jason just as his career was taking off, reflects on Nosaj’s rise: “Everyone here in K-Town thinks Nosaj Thing is a god. But if you ask him about his pride in being Korean, he won’t say anything.”

Andrew adds: “It’s just like how Qbert is for the Filipino community – that’s who Nosaj Thing is for Koreans today. When I went to South Korea to perform, they would ask me how I was affiliated with him, although I’m not really. South Koreans are amazed to see a Korean guy make it in the music industry in America with a sense of originality, not having to sell out.”

Both Andrew and Vince shift the conversation suddenly to Keith Ape and his debut as a trap music artist. Keith Ape’s success was due in part to spectacle (as the genre demands), to the power of hallyu promotion, but more so to simple respect from established artists such as Gucci Mane and Waka Flocka Flame. In a Noisey documentary about his first U.S. performance at South by Southwest (SXSW) in 2015, Keith Ape is translated as saying: “You know, I’m Asian. And I heard stories of how Asians are still looked at as outsiders in the States. And I heard it’s even worse when it comes down to hip-hop.”

While his successful Atlanta trap-style set at SXSW ultimately assuaged those fears of acceptance, for many beginning and working Asian American DJs and performers, this perceived and sometimes enforced musical barrier is daunting. While Andrew seemed to have his criticisms about how Korean promoters of Korean artists seem to be strictly focused on the commercial payoff of such events, he did not condemn their tapping into the United States market. Furthermore, he never mentioned that performing in the electronic music genre was either assisted or hindered by his ethnicity. Rather, much like Nosaj Thing, Malt lets the music do its work and create an audiotopia in which race and ethnicity are not under the spotlight. Literally, most of the shows Malt performs at do not feature the performer; the DJ is often in the dark, putting the focus almost exclusively on the music.

MALT, courtesy of Leisure Sports Records

Vince adds: “Korean American artists like Nosaj Thing and TOKiMONSTA and David Choe – all these people are doing their own thing. They’ve got these ‘don’t see me as Asian’ mottos, these ‘just think I’m dope’ vibes.”

Instead of searching for authenticity in the racial or ethnic identities of performers, Andrew is more interested in breaking stereotypes about the dangers associated with techno music, raves, and drug use. Andrew concludes: “I think first impressions are very, very important to Korean people. Looks are everything. South Korea is like the biggest plastic surgery country in the world. I went to Korea to visit my grandma, who I hadn’t seen in a long time, and all she would ask me was like, ‘Are you eating well? Look at your hair!’ Just purely about my looks. I was telling her, ‘Grandma! I run a label back in LA! I’m trying to be a musician!’ At our events, random Korean people walk by, they’ll come in for five seconds, listen to the music, and label it as ‘drug music,’ like something you listen to when you’re messed up. The same thing could be said about trap or EDM, right? But they don’t associate it with that. Hopefully, if the right timing comes, we can change that somehow.”

—

Featured Image: TOKiMONSTA by Twitter User Henry Faber, 2011 (CC BY-NC 2.0)

—

Shawn Higgins is the Academic Coordinator of the Undergraduate Bridge Program at Temple University’s Japan campus. His latest publication is “Orientalist Soundscapes, Barred Zones, and Irving Berlin’s China,” coming out in the 2018 volume of Chinese America: History and Perspectives.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“How Many Latinos are in this Motherfucking House?”: DJ Irene, Sonic Interpellations of Dissent and Queer Latinidad in ’90s Los Angeles—Eddy Francisco Alvarez Jr.

“How Many Latinos are in this Motherfucking House?”: DJ Irene, Sonic Interpellations of Dissent and Queer Latinidad in ’90s Los Angeles—Eddy Francisco Alvarez Jr.

Contra La Pared: Reggaetón and Dissonance in Naarm, Melbourne–Lucreccia Quintanilla

Recent Comments