“This AI will heat up any club”: Reggaetón and the Rise of the Cyborg Genre

This series listens to the political, gendered, queer(ed), racial engagements and class entanglements involved in proclaiming out loud: La-TIN-x. ChI-ca-NA. La-TI-ne. ChI-ca-n-@. Xi-can-x. Funded by an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation as part of the Crossing Latinidades Humanities Research Initiative, the Latinx Sound Cultures Studies Working Group critically considers the role of sound and listening in our formation as political subjects. Through both a comparative and cross-regional lens, we invite Latinx Sound Scholars to join us as we dialogue about our place within the larger fields of Chicanx/Latinx Studies and Sound Studies. We are delighted to publish our initial musings with Sounding Out!, a forum that has long prioritized sound from a queered, racial, working-class and “always-from-below” epistemological standpoint. —Ed. Dolores Inés Casillas

—

Busco la colaboración universal donde todos los Benitos puedan llegar a ser Bad Bunny. –FlowGPT, TikTok

In November of 2023, the reggaetón song “DEMO #5: NostalgIA” went viral on various digital platforms, particularly TikTok. The track, posted by user FlowGPT, makes use of artificial intelligence (Inteligencia Artificial) to imitate the voices of Justin Bieber, Bad Bunny, and Daddy Yankee. The song begins with a melody reminiscent of Justin Bieber’s 2015 pop hit “Sorry.” Soon, reggaetón’s characteristic boom-ch-boom-chick drumbeat drops, and the voices of the three artists come together to form a carefully crafted, unprecedented crossover.

Bad Bunny’s catchy verse “sal que te paso a buscar” quickly inundated TikTok feeds as users began to post videos of themselves dancing or lip-syncing to the song. The song was not only very good but it also successfully replicated these artists– their voices, their style, their vibe. Soon, the song exited the bounds of the digital and began to be played in clubs across Latin America, marking a thought-provoking novelty in the usual repertoire of reggaetón hits. In line with the current anxieties around generative AI, the song quickly generated public controversy. Only a few weeks after its release, ‘nostalgIA’ was taken down from most digital platforms.

The mind behind FlowGPT is Chilean producer Maury Senpai, who in a series of TikTok responses explained his mission of creative democratization in a genre that has been historically exclusive of certain creators. In one video, FlowGPT encourages listeners to contemplate the potential of this “algorithm” to allow songs by lesser-known artists and producers to reach the ears of many listeners, by replicating the voices of well-known singers. Maury Senpai’s production process involved lyric writing, extensive study of the singers’ vocals, and the Kits.ai tool.

Therefore, contrary to FlowGPT’s robotic brand, ‘nostalgIA’ was the product of careful collaboration between human and machine– or, what Ross Cole calls “cyborg creativity.” This hybridization enmeshes the artist and the listener, allowing diverse creators their creative desires. Cyborg creativity, of course, is not an inherent result of GenAI’s advent. Instead, I argue that reggaetón has long been embedded in a tradition of musical imitation and a deep reliance on technological tools, which in turn challenges popular concerns about machine-human artistic collaboration.

Many creators worry that GenAI will co-opt a practice that for a long time has been regarded as strictly human. GenAI’s reliance on pre-existing data threatens to hide the labor of artists who contributed to the model’s output. We may also add the inherent biases present in training data. Pasquinelli and Joler propose that the question “Can AI be creative?” be reformulated as “Is machine learning able to create works that are not imitations of the past?” Machine learning models detect patterns and styles in training data and then generate “random improvisation” within this data. Therefore, GenAI tools are not autonomous creative actors but often operate with generous human intervention that trains, monitors, and disseminates the products of these models.

The inability to define GenAI tools as inherently creative on their own does not mean they can’t be valuable for artists seeking to experiment in their work. Hearkening back to Donna Haraway’s concept of the cyborg, Ross Cole argues that

Such [AI] music is in fact a species of hybrid creativity predicated on the enmeshing of people and computers (…) We might, then, begin to see AI not as a threat to subjective expression, but another facet of music’s inherent sociality.

Many authors agree that unoriginal content—works that are essentially reshufflings of existing material—cannot be considered legitimate art. However, an examination of the history of the reggaetón genre invites us to question this idea. In “From Música Negra to Reggaetón Latino,” Wayne Marshall explains how the genre emerged from simultaneous and mutually-reinforcing processes in Panamá, Puerto Rico, and New York, where artists brought together elements of dancehall, reggae, and American hip hop. Towards the turn of the millennium, the genre’s incorporation of diverse musical elements and the availability of digital tools for production favored its commercialization across Latin America and the United States.

The imitation of previous artists has been embedded in the fabric of reggaetón from a very early stage. Some of the earliest examples of reggaetón were in fact Spanish lyrics placed over Jamaican dancehall riddims— instrumental tracks with characteristic melodies. When Spanish-speaking artists began to draw from dancehall, they used these same riddims in their songs, and continue to do so today. A notable example of this pattern is the Bam Bam riddim, which is famously used in the song “Murder She Wrote” by Chaka Demus & Pliers (1992).

This riddim made its way into several reggaetón hits, such as “El Taxi” by Osmani García, Pitbull, and Sensato (2015).

We may also observe reggaetón’s tradition of imitation in frequent references to “old school” artists by the “new school,” through beat sampling, remixes, and features. We see this in Karol G’s recent hit “GATÚBELA,” where she collaborates with Maldy, former member of the iconic Plan B duo.

Reggaetón’s deeply rooted tradition of “tribute-paying” also ties into its differentiation from other genres. As the genre grew in commercial value, perhaps to avoid copyright issues, producers cut down on their direct references to dancehall and instead favored synthesized backings. Marshall quotes DJ El Niño in saying that around the mid-90s, people began to use the term reggaetón to refer to “original beats” that did not solely rely on riddims but also employed synthesizer and sequencer software. In particular, the program Fruity Loops, initially launched in 1997, with “preset” sounds and effects provided producers with a wider set of possibilities for sonic innovation in the genre.

The influence of technology on music does not stop at its production but also seeps into its socialization. Today, listeners increasingly engage with music through AI-generated content. Ironically, following the release of Bad Bunny’s latest album, listeners expressed their discontent through AI-generated memes of his voice. One of the most viral ones consisted of Bad Bunny’s voice singing “en el McDonald’s no venden donas.”

The clip, originally sung by user Don Pollo, was modified using AI to sound like Bad Bunny, and then combined with reggaetón beats and the Bam Bam riddim. Many users referred to this sound as a representation of the light-heartedness they saw lacking in the artist’s new album. While Un Verano Sin Ti (2022) stood out as an upbeat summer album that addressed social issues such as U.S. imperialism and machismo, Nadie Sabe lo que va a Pasar Mañana (2023) consisted mostly of tiraderas or disses against other artists and left some listeners disappointed. In a 2018 post for SO!, Michael S. O’Brien speaks of this sonic meme phenomenon, where a sound and its repetition come to encapsulate collective discontent.

Another notorious case of AI-generated covers targets recent phenomenon Young Miko. As one of the first openly queer artists to break into the urban Latin mainstream, Young Miko filled a long-standing gap in the genre—the need for lyrics sung by a woman to another woman. Her distinctive voice has also been used in viral AI covers of songs such as “La Jeepeta,” and “LALA,” originally sung by male artists. To map Young Miko’s voice over reggaetón songs that advance hypermasculinity– through either a love for Jeeps or not-so-subtle oral sex– represents a creative reclamation of desire where the agent is no longer a man, but a woman. Jay Jolles writes of TikTok’s modifications to music production, namely the prioritization of viral success. The case of AI-generated reggaetón covers demonstrates how catchy reinterpretations of an artist’s work can offer listeners a chance to influence the music they enjoy, allowing them to shape it to their own tastes.

Examining the history of musical imitation and digital innovation in reggaetón expands the bounds of artistry as defined by GenAI theorists. In the conventions of the TikTok platform, listeners have found a way to participate in the artistry of imitation that has long defined the genre. The case of FlowGPT, along with the overwhelmingly positive reception of “nostalgIA,” point towards a future where the boundaries between the listener and the artist are blurred, and where technology and digital spaces are the platforms that allow for an enhanced cyborg creativity to take place.

—

Featured Image: Screenshot from ““en el McDonald’s no venden donas.” Taken by SO!

—

Laurisa Sastoque is a Colombian scholar of digital humanities, history, and storytelling. She works as a Digital Preservation Training Officer at the University of Southampton, where she collaborates with the Digital Humanities Team to promote best practices in digital preservation across Galleries/Gardens, Libraries, Archives, and Museums (GLAM), and other sectors. She completed an MPhil in Digital Humanities from the University of Cambridge as a Gates Cambridge scholar. She holds a B.A. in History, Creative Writing, and Data Science (Minor) from Northwestern University.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Boom! Boom! Boom!: Banda, Dissident Vibrations, and Sonic Gentrification in Mazatlán—Kristie Valdez-Guillen

Listening to MAGA Politics within US/Mexico’s Lucha Libre –Esther Díaz Martín and Rebeca Rivas

Ronca Realness: Voices that Sound the Sucia Body—Cloe Gentile Reyes

Echoes in Transit: Loudly Waiting at the Paso del Norte Border Region—José Manuel Flores & Dolores Inés Casillas

Experiments in Agent-based Sonic Composition—Andreas Pape

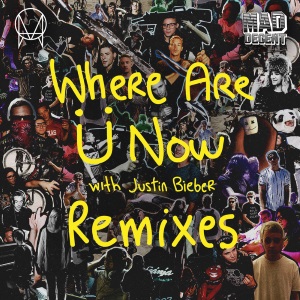

Of Resilience and Men: How Bieber, Skrillex, and Diplo Play with Gender in “Where Are Ü Now”

Justin Bieber caught me off guard last year. There I was, minding my own business, listening to a pop station, and this breathy little thing, this delicate vocal wrapped in a halo of shimmering effects starts piping through my car. I didn’t even realize it was him at first; it had been so long since I’d heard a new Bieber song. And I had no clue the production was from Skrillex and Diplo (from their 2015 Skrillex and Diplo Present Jack Ü), which is why I was probably also not ready for the drop, that moment when the song’s tension releases and I’m suddenly gliding across a syncopated bass synth while Bieber’s vocals are pinched into a dolphin call. Somehow, two of the most notoriously unsubtle producers and the posterboy for “too much, too soon” had snuck up on me with “Where Are Ü Now” (WAÜN).

WAÜN’s drop from nowhere isn’t brand new. Subtle soars and understated drops are officially A Thing. More importantly, they do work beyond the sonic aesthetic. In this case, I want to listen to WAÜN in the context of Bieber’s performance of gender, specifically with an ear toward the way Skrillex and Diplo mix elements from dancepop’s 2015 toolkit to produce a track that plays on feminine tropes, which articulate a kind of masculinity. Listening to WAÜN alongside Robin James’s Resilience & Melancholy (2015) amplifies the male privilege at play in WAÜN. James calls attention to the way drops can sonify feminine resilience, and WAÜN’s surprise drop toys with that resilience in a thoroughly heteromasculine way. I’ll first set up how drops usually work, then read James in the context of Bieber’s gender performance as heard in WAÜN.

WAÜN’s drop from nowhere isn’t brand new. Subtle soars and understated drops are officially A Thing. More importantly, they do work beyond the sonic aesthetic. In this case, I want to listen to WAÜN in the context of Bieber’s performance of gender, specifically with an ear toward the way Skrillex and Diplo mix elements from dancepop’s 2015 toolkit to produce a track that plays on feminine tropes, which articulate a kind of masculinity. Listening to WAÜN alongside Robin James’s Resilience & Melancholy (2015) amplifies the male privilege at play in WAÜN. James calls attention to the way drops can sonify feminine resilience, and WAÜN’s surprise drop toys with that resilience in a thoroughly heteromasculine way. I’ll first set up how drops usually work, then read James in the context of Bieber’s gender performance as heard in WAÜN.

Drops, at their most basic, are climactic moments when a song’s full instrumental measure hits (hence “drop”), often after some key elements of the instrumental have been removed so that the climax can sound more intense. At that broad level, any genre can employ a drop of some sort. EDM and dancepop drops—the kind that most directly inform the music of Skrillex, Diplo, and Bieber—are bass-heavy and typically follow a soar that intensifies volume, texture, rhythm, and/or pitch: you soar to a sonic plateau or a cliff, and with a “YEEEEEES!!!!!” coast on some wobbly goodness to the next verse.

The pre-chorus soar in the Messengers/Sir Nolan/Kuk Harrell-produced “All Around the World” from Bieber’s 2012 Believe is a solid example. In the video below, the soar starts at 0:45, the chorus enters at 1:00, and the drop lands at 1:15. It’s textbook: the instrumental is stripped back and filtered, and in the opening moments, we hear a descending bass glide. A filter does what its name suggests–it filters out a prescribed set of frequencies so that we only hear a certain range, and in this case it’s the low end that comes through. The effect makes the synths sound like they’re pulsating through water, and the higher frequency overtones take on a shimmery quality. Over the course of the 8-measure soar, the higher frequency range is brought into earshot, and then, on the second half of the eighth measure…nothing. This nothingness is integral to James’s central argument in Resilience & Melancholy: nothingness intensifies what follows. In these eight measures, we’ve glided down to the low end only to soar up up up until all that’s left is Bieber’s voice, confident, nasally, with just a touch of autotune as he sings the titular line that will take us to the chorus. That chorus bangs harder because of the soar to oblivion before it.

WAÜN’s drop lands at 1:09. For full context, start from the beginning and listen for the soar. (If you also need to stare dreamily into Bieber’s eyes, then by all means.)

There’s not really a soar there. No intensifying volume, texture, rhythm, pitch. The not-soar (starting at 0:48) is even a weird length, clocking in at 12 measures after an 8-measure intro and 16-measure verse have established a multiples-of-8 structural rhythm; even if we were expecting a drop, it comes four measures early. The clearest sign we get that a drop is imminent is that moment where the instrumental reduces to a quiet hiss for two measures as Bieber sings “Where are you now?” That hiss is the structural equivalent of the nothingness we hear just before “All Around the World”’s chorus, and with no traditional soar before it, we have just enough time to think “Oh shit, are they gonna….?” before we’re off, clutching tight to Justin Bieber as we ride a dolphin through the more tender parts of Skrillex’s and Diplo’s musical oceans.

Until that nothingness, this could just as easily be one of those heartfelt Bieber tunes where he reaches to the high end of his range for a chorus full of feels. That Bieber? He’s incredibly self-assured, bearing his soul because he’s certain you’ll love him. The bait-and-switch of WAÜN’s soarless drop highlights Bieber’s insecurity in this song—he’s just dolphin calls and “Where are you now”s—by creating expectations for a different persona.

So what we have here is an atypical drop, a drop that calls attention to itself by behaving differently than we expect it to, a drop that’s a study in understatement–all courtesy of three of dancepop’s resident maximalists.

“143 Diplo and Skrillex at Burning Man 2014 Opulent Temple” by Flickr user Duncan Rawlinson, CC BY-NC 2.0

Atypical soars and drops aren’t new, as producers will always toy with musical conventions as a way to disrupt expectations. Skrillex’s own “Scary Monsters and Nice Sprites” (2010) includes a pre-drop that doesn’t soar at all. In 2015, two big acts in the dance scene, Disclosure and The Chemical Brothers, released singles that don’t soar right, either. Disclosure, whose big 2013 hit “Latch” soared rather traditionally into Sam Smith’s chorus, is coyer on “Bang That” and “Jaded.” “Bang That” includes three separate 8-measure phrases (at 0:30, 0:45, and 1:01, respectively, in the linked video) that never take off, finally settling into a descending bass line (starting at 1:09) that just repeats a rhythmic motif, running out the clock on the final four measures before the chorus. “Jaded,” at the other end of the spectrum, includes only a 4-measure pre-chorus (1:18-1:27) that seems to be sweeping upward like a traditional soar, then roller coasters down and back up over the final two measures. The instability of this soar/not-soar is punctuated with an additional eighth note tacked onto the end of the fourth measure, throwing the chorus off-kilter. The Chemical Brothers employ a similar roller coaster sweep in “Sometimes I Feel So Deserted” that marks out an even eight measures (0:58-1:13) without either intensifying rhythmically or pushing to a pitch ceiling at the drop.

These soars and drops stand out precisely because, like WAÜN’s, they aren’t the norm. To help theorize WAÜN’s not-soar, I want to think with Robin James, whose Resilience & Melancholy hears soars and drops in the context of contemporary race and gender politics. James situates soars and drops as the sonic equivalent of resilience–a performance of feminine overcoming that ultimately only strengthens the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy that inflicts the damage that is being surmounted. In other words, women can only attempt to overcome through the damage that white supremacist capitalist patriarchy inflicts upon them. Sonically, the soar is an accrual of damage that is spectacularly (and profitably) overcome in the drop, the music that resiliently endures on the other side of nothingness. Melancholy, on the other hand, is failed resilience, a handling of damage that does not directly profit white supremacist patriarchy and that could sound any number of ways, including like a non-traditional soar. While admittedly these soars and drops aren’t always about gender politics, R&M opens space for us to think about gender and soars/drops together.

I don’t think WAÜN’s non-soar/drop is resilient or melancholic, but I do think it’s helpful to think of it as being about resilience and melancholy. This is where Bieber’s performance of masculinity comes into play. From his earliest poofy-headed, babyfaced performances, Biebs has done a modified bro thing: his heart’s on his sleeve, but mostly as a strategy for sexual conquest. “All Around the World,” again, is exemplary. In the lyrics, Bieber uses his worldly experiences to woo a potential lover, who he also negs, keeping himself in a position of power as someone who knows more, has seen more, and is willing to accept this woman despite her obvious flaws.

“143 Diplo and Skrillex at Burning Man 2014 Opulent Temple” by Flickr user Duncan Rawlinson, CC BY-NC 2.0

In WAÜN, though, I hear his performance of masculinity complicated further, as he tries out a number of more feminized tropes all at once. Lyrically, Bieber is the scorned lover who claims to have done all the care work in his relationship. Visually, he’s the pop icon whose body is ogled, scrutinized, and marked. Vocally, he receives the pitch-shift treatment that has most recently been associated with DJ Snake’s production of diva vocals (think “You Know You Like It” and “Lean On”). He also sings in a breathy style that James has elsewhere noted mimics Ellie Goulding’s vocals. Musically, Skrillex and Diplo give him the soar/drop construction to undergird his pain, a musical technique that most often signifies feminine resilience.

What bubbles up is a heteromasculine play on resilience and melancholy. Skrillex and Diplo liquidate the soar until all that’s left is a nothing-hiss before the drop. In the context of the other feminized tropes Bieber is messing with in WAÜN, this failed soar could feel melancholic, a refusal to spectacularly overcome. Overcome what, though? Bieber gets to sound resilient or melancholic without ever experiencing damage. That’s his male privilege. James points out that one of the most violent outcomes of resilience discourse is the re-enforcement of damage. If resilience is the way women become legible and profitable, then the damage inflicted by ablist white cisheteropatriarchy becomes a necessity, something that must be endured to gain access to power and resources. This is the lynchpin of James’s critique: resilience is a harmful discourse because it ultimately benefits the system it purports to overcome. Melancholy turns resilience logic on its head by refusing to treat damage as something an individual is responsible for overcoming. WAÜN, though, erases damage altogether in its initial drop. WAÜN’s feminized tropes ultimately highlight instead of unsettle Bieber’s performance of hetero-masculinity: what’s more man-ly than accessing power and resources without the threat of institutional violence?

Importantly, these feminized tropes don’t undermine Bieber’s heteromasculine performance; rather, they only seem to add nuance to the slightly bro-ier [that’s a word] Bieber performance we’ve become accustomed to. That’s what I mean when I say WAÜN is about resilience and melancholy; Skrillex and Diplo use the markers of queer or feminine overcoming and failed overcoming to re-construct Bieber’s masculinity, to toss some more ingredients into his manly mix, and the not-soar is a big component of that. Skrillex and Diplo tap into this soar experimentation, then drop it into the middle of a slightly more gender-fluid Bieber.

Screenshot from “Where Are Ü Now” official video

WAÜN’s high water mark is a few months behind us at this point, but Bieber remains hotter than ever, with “What Do You Mean?,” “Sorry” (another Skrillex production credit), and “Love Yourself” still dominating US and UK charts. Several more singles from Purpose (including two more Skrillex collaborations) are poised to do the same in 2016. Each of these singles extends some of the same tropes Bieber, Skrillex, and Diplo explore in WAÜN—breathy vocals, misunderstood and mistreated pop icon, resilience and contrition and care in the face of a failed relationship—and I hear WAÜN’s initial drop as the sonic moment that preps Bieber’s return to the pop charts. He wades back into the mainstream with a more complex performance of heteromasculinity and reaps the profits that come with it.

—

Justin D Burton is Assistant Professor of Music at Rider University, and a regular writer at Sounding Out!. His research revolves around critical race and gender theory in hip hop and pop, and his current book project is called Posthuman Pop. He is co-editor with Ali Colleen Neff of the Journal of Popular Music Studies 27:4, “Sounding Global Southernness,” and with Jason Lee Oakes of the Oxford Handbook of Hip Hop Music Studies (2017). You can catch him at justindburton.com and on Twitter @justindburton. His favorite rapper is Right Said Fred.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Vocal Gender and the Gendered Soundscape: At the Intersection of Gender Studies and Sound Studies — Christine Ehrick

They Do Not All Sound Alike: Sampling Kathleen Cleaver, Assata Shakur, and Angela Davis — Tara Betts

Tomahawk Chopped and Screwed: The Indeterminacy of Listening–Justin Burton

Recent Comments