“Everyone I listen to, fake patois. . .”

It may seem a little crazy to take Das Racist seriously. Their songs are deep in the realm of the ridiculous, but I can’t help but feel that “Combination Pizza Hut/Taco Bell” is a commentary on how the compression of urban space is shaped by our relationship to consumption. Close-reading of their songs provide repeated evidence for the underlying tenor of seriousness in that absurdity—even if they’re being playful about it. As one of my favorite Das Racist songs says, “we’re not joking / just joking / we are joking / just joking / we’re not joking.” (For those who need help parsing, no, they are in fact, not joking). Take for instance Das Racist’s “Fake Patois” off of their free downloadable “mixtape” Shut Up, Dude! (2010). This satirical and intelligent exploration of the sounds of authenticity and their relationship to the reggae-hip hop dyad uses fake patois itself, working off an ironic tension that is as troubling as it is funny—and it’s also a banging song.

The “patois” used in American hip hop is clearly meant to be Jamaican-sounding, mixing elements of Jamaican creole language with a generous sprinkling of terms specific to Rastafarian English. The sounds of “fake patios” are a stylistic choice, reinforced through a dancehall reggae cadence of rapid-fire clipped words, rapped melodically. “Fake Patois” recalls the role of reggae in identifying an authentic origin for hip-hop. And certainly the connection cannot be denied. That Kool Herc brought Jamaican DJ culture with him to the Bronx is originary, and Run D.M.C brought it up in 1984’s “Roots, Rap, Reggae” (featuring Yellowman). If you want a more detailed mapping of a particular reggae meme’s journey through hip hop, check out Wayne Marshall’s fantastic essay on the subject, which demonstrates that even when contemporary artists think they are paying homage by imitating their rap fore-bearers they are also unknowingly paying homage to the influence of Jamaican music on American rap.

.

Das Racist’s “Fake Patois” speaks with a deep awareness of this tradition in rapping, but what may on the surface seem like an indictment of the “fake” nature of the adopted style is actually an example of what George Lipsitz called “strategic anti-essentialism” in Dangerous Crossroads. While critical of reckless appropriation of various ethnic musics by western whites, Lipstiz nevertheless sees this music as a way for individuals to express their identity through solidarity, sharing a respect for that music’s history as it is embedded in a framework of power. The song shows this respect through its knowledge, but also immediately calling out artists that have used the “fake patois,”—respected ones like KRS-One, b ut also “My man Snow,” a white Canadian performer of dancehall reggae. Snow is probably the quintessential example of the “fake patois,” as his 1993 break-out hit, “Informer” was for much of white America the first exposure to the sounds of dancehall reggae. Snow withstood attacks on his authenticity throughout his career and tried to shore it up through his incarceration narratives and associations with blacks of Caribbean descent.

ut also “My man Snow,” a white Canadian performer of dancehall reggae. Snow is probably the quintessential example of the “fake patois,” as his 1993 break-out hit, “Informer” was for much of white America the first exposure to the sounds of dancehall reggae. Snow withstood attacks on his authenticity throughout his career and tried to shore it up through his incarceration narratives and associations with blacks of Caribbean descent.

Das Racist doesn’t limit their list to musicians, and their choices highlight the different ways patois is put to work. For example, they mention Miss Cleo of psychic phoneline fame, who claimed to be from Jamaica, but is an actress and playwright from Seattle. Through her patois the Miss Cleo character sold the authentic origins of her mystic powers. Das Racist seems to be suggesting that the use of the patois sound in songs is selling something as well, even as they use it to sell their own song.

.

Similarly, the lyric, “Even Jim Carrey fuck with the patois,” makes reference to the actor’s parody of Snow’s “Informer.” While “Imposter,” is clearly meant to call out Snow’s lack of ‘blackness,’ Carrey’s mocking “Day-O” and his characterization of dancehall lyrics as “gibberish” also underlines a disdain for the music form itself. While potentially problematic, Snow’s performance is clearly born of an earnest appreciation of dancehall reggae. The parody, on the other hand, despite its comedic intent, does not have the performer’s genuine affect to mitigate its buffoonish mimicry.

"Even Jay-Z did a fake patois" by Flickr User NRK P3

Das Racist’s song also reveals a degree of comedic intent. The use of autotune highlights the artificiality of the sung patois. Their straight delivery of ridiculous references (“Crunch like Nestle. . .Snipe like Wesley”) and their use of repetition to re-emphasize the absurdity of their performance is funny. They revel in the dumb fun of referencing Half-Baked—when Dave Chappelle, posing as a Jamaican, is asked what part of Jamaica he is from and he replies “right near the beach.” Das Racist’s demonstrated mix of absurdity and awareness destabilizes their position as a means to open up a field of possibilities. It does not set limits by associating authenticity with a singular origin, but rather to establish it as a connection with an ongoing tradition.

The song continues to question the stability of the authentic by calling out two singers with a “real” patois, Shabba Ranks and Cutty Ranks, for their past homophobic songs and comments. Das Racist sings, “Your M.O. Is ‘mo / Me say no thanks.” That “’mo” is short for “homo,” and that “no thanks”serves to distance them from the popular examples of male Jamaican artists whose homophobia has been linked with a hypermasculine ideal played out through violent fantasy—whether it’s Shabba’s defense of Buju Banton’s “Boom Bye Bye” or Cutty’s “Limb By Limb.” Their apologies attempted to connect their bias with their “culture,” trying to excuse their ideas in terms of how they authentically inform their problematic songs. In this lyric, Das Racist is implicitly rejecting homophobia as a litmus for authenticity, while playing with a homophobic term. In other words, for artists like Shabba and Cutty to defend homophobia in reference to a “realness” in their music is suggesting that bias against gays is a precondition for making “real” music.

For me, the broader question that emerges from this interrogation of “fake patois” is: to what degree can a variety of popular music sound choices (singing style, melodic influence, etc that are associated with a particular culture or nationality) be similarly destabilized or revealed as “fake”? The Beatles sang like fake Americans, imitating their favorite (mostly black) artists, and Green Day have sounded like fake Brits, identifying with some authenticating element found in the sound of English punks. What ground does this destabilization open up? What possibilities for connection does it provide and what framework can we use to discuss it when the results seem problematic?

Lipsitz writes, “In its most utopian moments, popular culture offers a promise of reconciliation to groups divided by power, opportunity and experience,” and Das Racist certainly seems to be doing their best to critically fulfill that promise. Their self-conscious undermining of their position and their willingness to simultaneously suggest that there may be something problematic with mimicking patois–while highlighting that so-called authentic identities are sutured together into a particular kind of sounded performance–articulates a bond through an identification, not a singular origin. In doing so, Das Racist suggest a network of identities bound by points of solidarity, making room for South Asia in the Black Atlantic by way of the Caribbean.

—

Osvaldo Oyola is a regular contributor to Sounding Out! and ABD in English at Binghamton University.

Hearing the Tenor of the Vendler/Dove Conversation: Race, Listening, and the “Noise” of Texts

In the beginning there were no words. In the beginning was the sound and they all knew what the sound sounded like. –Toni Morrison, Beloved

A conversation in my Black Feminist Theories class on the two versions of Sojourner Truth’s famous speech from the Ohio Women’s Convention—the one published in 1863 that renders her words in a black southern dialect or the 1851 version that does not—elicited the following story about listening. A black male student was student teaching/observing in a classroom — the teacher was white, the student teacher black. The exercise he observed involved transcribing speech and then reading it back. A black male student in the classroom spoke and the white teacher and black student teacher each transcribed the speech and read their transcriptions aloud. The white teacher’s transcription/recording was in dialect, the black student teacher’s was not. The student teacher maintained that what and how the white teacher heard the black student was not, in fact, either what or how the black student spoke.

Discussions like these have spurred me to meditate more deeply on sound. And now that I’ve really begun to consider it, texts have become much noisier places; the white spaces and black marks becoming places for reading and hearing. Thinking more deeply about sonic affinities and communities has helped me really begin to understand how sound shapes sight and sight shapes sound.

An example: Since reading Fred Moten’s In the Break, in particular “The Resistance of the Object,” it’s not only impossible for me to read the scene of Captain Anthony’s beating/rape of Aunt Hester in Frederick Douglass’s Narrative without hearing Abbey Lincoln’s hums, moans, and screams, it is not possible for me to read the entire text without populating it with sound, even as those sounds are, in my imagining of them, not always specific.

.

Perhaps it’s most accurate to say that I am aware that the world that the text references is a world filled with sounds peculiar to it, many of which may no longer be present in our contemporary world. At the same time, I try to bring at least some of those sounds—talking drums, field hollers, whips cracking, the sounds of chains, etc.—and approximations of sounds into the classroom when I teach Douglass’s Narrative and My Bondage and My Freedom (as well as when I teach other texts).

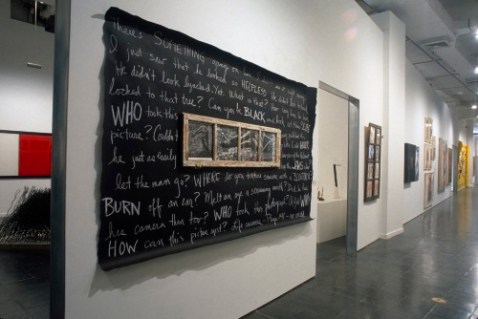

In “The Word and the Sound: Listening to the Sonic Colour-line in Frederick Douglass’s 1845 Narrative” (2011) Jennifer Stoever-Ackerman writes, “The emphasis Douglass places on divergent listening practices shows how they shape (and are shaped by) race, exposing and resisting the aural edge of the ostensibly visual culture of white supremacy, what I have termed the “sonic colour-line” (21). Stoever-Ackerman riffs on Elizabeth Alexander’s “Can you be BLACK and Look at This: Reading the Rodney King Video” (and Alexander riffs on Pat Ward Williams’s “Accused, Blowtorch, Padlock”) to ask, “Can you be WHITE and (really) LISTEN to this?” or alternatively, “Are you white because of HOW you listen to this?” (21).

Pat Ward Williams's "Accused/Blowtorch/Padlock" (1986), Courtesy of the Artist and the New Museum, New York

.

In his review of Shane White and Graham White’s The Sounds of Slavery: Discovering African American History Through Songs, Sermons, and Speech (Beacon Press, 2005) in the July 2009 issue of the Journal of Urban History, Robert Desrochers contrasts the abolitionists who were attuned to how to make a white audience hear the sounds that surrounded and produced the (performances of the formerly) enslaved, to the “Virginia patriarch who failed to mention the singing of his slaves even once in a diary that ran to hundreds of manuscript pages” (754). Given these examples of the ways that many white ears had to be systematically attuned to hearing slavery’s sounds as well as the understanding that, “the very things that made slave sounds distinctive—chants, grunts, and groans; melismatic, repetitious, and improvisational lyric play; pitch and tonal inflections and cadences; timbral variations, polyrhythms, and heterophonic harmonies—struck whites mostly as strange, inappropriate, wrong” (754)—the answers to Stoever-Ackerman’s questions may be respectively “no” and “yes” (or several combinations of no and yes), particularly if we engage “whiteness” as an ideology and not simply (or not only) a “raced” description of those people constituted socially and legally as (presumably) white.

It was with these kinds of questions of sound and sonic whiteness on my mind (especially this question of who hears, who doesn’t hear, and then again what is and isn’t heard) that I read and was brought up short by Helen Vendler’s recent November 24, 2011 New York Review of Books review of Rita Dove’s The Penguin Anthology of 20th Century American Poetry. In this piece, Vendler takes Dove to task for what she considers the anthology’s over-inclusiveness (“No century in the evolution of poetry in English ever had 175 poets worth reading”), the “accessibility” of the poems (“short poems of rather restricted vocabulary”), and the appearance of a large number of black and other non-white poets in the latter part of the twentieth-century. In short, from Vendler’s perspective, Dove is choosing “sociology” and complaint over artistry; mixing the wheat and the chaff.

It was with these kinds of questions of sound and sonic whiteness on my mind (especially this question of who hears, who doesn’t hear, and then again what is and isn’t heard) that I read and was brought up short by Helen Vendler’s recent November 24, 2011 New York Review of Books review of Rita Dove’s The Penguin Anthology of 20th Century American Poetry. In this piece, Vendler takes Dove to task for what she considers the anthology’s over-inclusiveness (“No century in the evolution of poetry in English ever had 175 poets worth reading”), the “accessibility” of the poems (“short poems of rather restricted vocabulary”), and the appearance of a large number of black and other non-white poets in the latter part of the twentieth-century. In short, from Vendler’s perspective, Dove is choosing “sociology” and complaint over artistry; mixing the wheat and the chaff.

Vendler writes, “Rita Dove, a recent poet laureate (1993–1995), has decided, in her new anthology of poetry of the past century, to shift the balance, introducing more black poets and giving them significant amounts of space, in some cases more space than is given to better-known authors. These writers are included in some cases for their representative themes rather than their style. Dove is at pains to include angry outbursts as well as artistically ambitious meditations.”

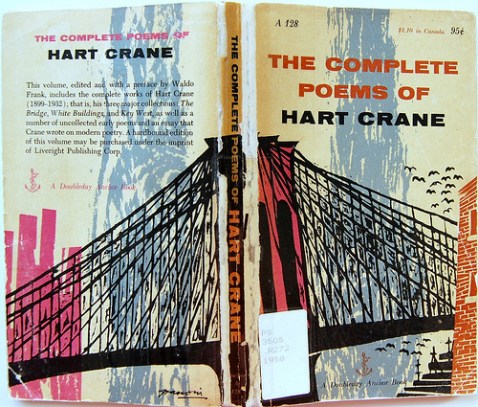

And Vendler on Dove on Hart Crane: “sometimes one wonders whether Dove is being hasty. She speaks, for instance, of ‘the cacophony of urban life on Hart Crane’s bridge.’ But the bridge in his ‘Proem’ exhibits no noisy ‘cacophony’; its panorama is a silent one. The seagull flies over it; the madman noiselessly leaps from ‘the speechless caravan’ into the water; its cables breathe the North Atlantic; the traffic lights condense eternity as they skim the bridge’s curve, which resembles a ‘sigh of stars’; the speaker watches in silence under the shadow of the pier; and the bridge vaults the sea. The automatic—and not apt—association of an urban scene with noise has generated Dove’s ‘cacophony.’”

Why does Vendler insist on silence where Dove joins sight and sound? That Vendler imagines silence and takes Dove to task for attaching cacophony to the city scene in the bridge poem is a struggle over meaning, over epistemology and ontology. How is Vendler registering not only the poem but also the entire text differently? This isn’t the only instance of Vendler’s insistent sonic “whiteness” whereby and wherein the reading of the poem, the anthology, and the anthologizer herself are disciplined.

Speechlessness though, is not soundlessness, and it seems to me that Dove locates herself on the bridge (and in the soundscape of the contemporary written poem) such that she hears the water, the seagull, and the leap and curve and flap of gull and man. As Dove herself responded (also in the New York Review of Books), “A cursory sweep over just the section [Vendler] excerpted in my anthology yields a host of extraordinary sounds: what with trains whistling their “wail into distances,” chanting road gangs, papooses crying—even men crunching down on tobacco quid—my gasp of surprise at Vendler’s blunder can barely be heard.”

In Vendler’s remarks and Dove’s response we might read the kind of cultural dissonance that continues to both construct and give insight into how different communities of readers and listeners are formed and the ways they are and aren’t racialized. By the end of the review, Vendler wants to be heard by those whom she imagines as the anthology’s likely readers: she wants to turn to them and “say,” to “cry out,” that there are better poems than those included here. For the sounds that in this anthology that Vendler hears most often in the “minor” poems, in the “minority” poets, and the “minority” anthologizer, are simplicity, noise, and needless complaint. And Vendler and Dove have been here before – see Vendler on Dove and Delaney on Vendler and Dove.)

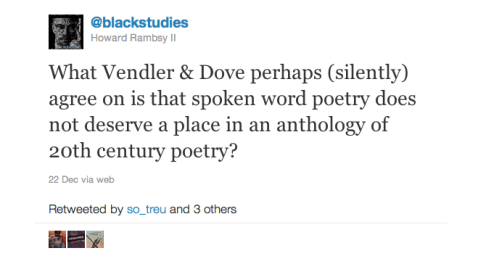

But despite the debate putting poetry front and center and enacting ways that it matters, Vendler’s critique and Dove’s response are each conservative, though in quite different ways. Neither Vendler nor Dove in the review, anthology, and defense of the anthology imagines the inclusion of spoken word, hip-hop (see Howard Rambsy II), and other forms of contemporary rhyme and verse that speak to a broad range of audiences across race, sex, and class. The inclusion of rap might further change the tenor of the conversation, opening up in important ways the debate over what counts as poetry, and expanding how black musical and poetic forms are heard and by whom.

—

Christina Sharpe is Associate Professor of English and American Studies at Tufts University where she also directs American Studies. Her book Monstrous Intimacies: Making Post-Slavery Subjects was published in 2010 by Duke University Press. Her current book project is Memory for Forgetting: Blackness, Whiteness, and Cultures of Surprise.

Recent Comments