The Sound of Hippiesomething, or Drum Circles at #OccupyWallStreet

Last week’s news was been full of alarming stories of real and threatened violence at various #Occupy sites around America. But also disturbing were the reports that complaints about the continuous drumming at the Occupy Wall Street site in Lower Manhattan were threatening to shut the entire operation down. According to stories in N + 1, slate.com, Mother Jones, and New York, the ten hour marathon drum circles at Zuccotti Park have been a focal point of mounting tensions, both between the occupiers and the drummers, and between the occupiers and the community at large. Last week, community members asked that the drummers limit their drumming to 2 hours a day, a request backed by actual OWS protesters. The drummers, loosely organized in a group called PULSE, initially resisted the restriction, claiming that such requests mimicked those of the government they were protesting against. Since then, a compromise has been worked out, but the situation gives rise to a host of questions about race, sound, drums, and protest.

Community organizers both inside and outside OWS said they were distressed by the continuous noise that these protesters are making, and certainly they had reason: as Jon Stewart put it in his episode of talking points, “it’s a public space, it’s for everyone, including people who don’t consider drum circles to be sleepy time music.”

Writer and singer Henry Rollins agrees, telling LA Weekly that he dreams of an #Occupy Music festival, because “So far [he has] heard people playing drums and other percussion instruments” but still wonders “if there will be a band or bands who will be a musical voice to this rapidly growing gathering of citizens.” Rage Against the Machine guitarist and frequent #Occupier Tom Morello also seems to concur, telling Rolling Stone, “Normally protests of this nature are furtive things, It’ll be 12 people with a small drum circle and a couple of red flags. But this has become something that people feel part of.” Stewart, Rollins, and Morello all have a point: not everyone likes drum circles, in fact some people feel quite strongly about them, which has the potential to be divisive for a movement famously representing “the 99%.”

But over and above the questions of musical taste, the very audible presence of snare drums, cymbals, and entire drum sets at OWS—more often found in marching bands or suburban garage band practice spaces than the usual drum circle staple, the conga—raises a different set of questions, both sonic and social, around the interrelated issues of “noise,” public space, and privilege.

That a drum circle populated by a large number of bad, mostly white drummers is being touted as “the sound” of occupation isn’t that surprising, at least not for alumni of UC Berkeley.

In my day, a more conga-oriented drum circle sprouted up on Sproul Plaza every Sunday; today, a similar one occupies a green space in Golden Gate Park right across from Hippie Hill, pretty much 24/7. (I walk by it every Thursday on my way to the gourmet food trucks: happily, the delicious smell of garlic noodles and duck taco obliviates all other senses.)

These kinds of regular, yet impromptu, circles abound in California and elsewhere: indeed, the sound of drum circles à la OWS has characterized certain types of social spaces for the last forty years. But what exactly does the sound of drum circles characterize? What meaning is being made by them, and why?

In the Americas, drum circles go back hundreds of years– many indigenous peoples have drumming traditions, for example, and, in Congo Square in New Orleans, slaves of African ancestry gathered weekly to dance to the rhythms they played on the bamboula, a bamboo drum with African origins, beginning in the early 1700s. The notion of the “circle” was a fundamental part of the dancing and music making at Congo Square—according to Gary Donaldson, the circles represented the memories of African nationalities and various reunited tribes people—and was echoed in various types of “ring shouts” across the West Indies and the Southern U.S. The contemporary drum circle stand-by, the conga, also came to the Americas via the forced migration of slaves; it is of Cuban origin but with antecedents in Africa, like the bamboula. The black power movements of the 1960s drew on this history—and sound—to good effect, reigniting semi-permanent drum circles in many U.S. neighborhoods– like the formal gathering that meets in Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem on Saturdays that is currently also under fire from a nearby condo association –audibly announcing their presence and enacting new community formations.

Given this history–and without erasing the presence of drummers of color at OWS--it can seem puzzling how the drum circle has come to occupy such a curiously whitened position in America’s cultural zeitgeist. Furthermore, one of the more problematic aspects of the OWS drum circle debate is the racialized implications of the instrumentation there—implications borne out by videos of OWS that show an overabundance of snares, some of the loudest drums available. According to percussionist Joe Taglieri, “no conga is louder than a fiberglass drum with a synthetic head.” If snares are louder than congas, then noise – actual decibel level — is probably not the sole issue when community groups attempt to control or oust drummers like those in Marcus Garvey Park. It does seem to be a key point of contention at OWS, however.

While there is also a history of African American marching bands, especially in the South, snare drums speak to a different set of American cultural traditions. Drum kits themselves evolved from Vaudeville, when theater space restrictions (and tight pay rolls) precluded inviting a large marching band inside. Mainstream associations with snares include but are not limited to army parades, high school marching bands, and of course hard rock music. Sometimes, like in the case of Tommy Lee, it is an unholy alliance of several of these contexts.

In other words, outside of OWS, snares are hardly the sound of social upheaval.

How the drum circle became associated with political protest in the first place is interesting. Although people sometimes associate drum circles with beatniks rather than hippies, a case could be made that they actually connect more strongly to an electrified Woodstock rather than an acoustic Bleecker Street, thanks in part to Michael Shrieve’s widely mediated turn during Santana’s performance of “Soul Sacrifice” at the 1969 festival.

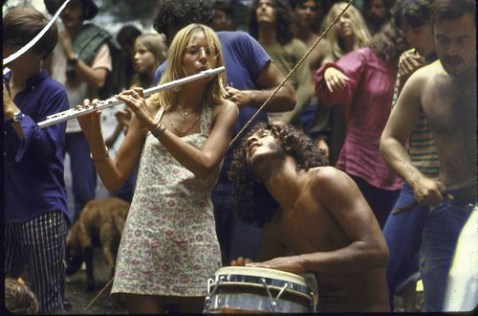

It is important to note that Shrieve is playing the traps in this sequence, not the conga, which is one reason I’d like to suggest that something about that scene – the hands on the congas, the grins of the other guys, the ecstatic face of a 20-year-old as he slams his kit, and the fetishistic gaze of the camera on the sticks, the skins and the cymbals – caught the imagination of a particular segment of American society. Santana’s band – two Mexican Americans (Carlos Santana and Mike Carabello), a Nicaraguan (Chepito Areas), two whites (Shrieve and Gregg Rolie, who later plagued the world in Journey) and an African American (bassist David Brown)—was truly multi-racial, creating a “small world” visual that furthered Woodstock’s utopian rhetoric in ways that were surely not borne out by the demographics of its audience. More importantly perhaps, the Woodstock movie showed a white suburban hippie guy as an equal participant in a multi-ethnic rhythmic stew, a powerful image in the 1960s. Indeed, the Santana performance may be precisely the moment when the idea of the drum circle was lifted from the context of “black power” and moved into the hippie mainstream.

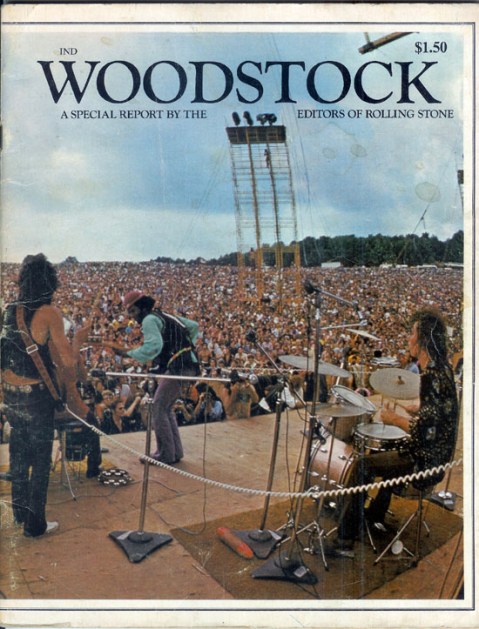

When's the last time you've seen a drummer on a magazine cover?: Santana on Rolling Stone's Woodstock special issue

Woodstock made congas hip to the mass of America—not just in Santana’s set but also in the performances of Richie Havens and Jimi Hendrix—and Woodstock helped define what the drum circle meant, in part by encapsulating certain discursive tropes that were very particular to those times. For example, drum circles epitomize the ’60s idea that political action is simultaneously self-expressive and collective. If a crowd of people sing “We Shall Overcome” or chant “Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh/The NLF is going to win,” it is a a collective act. It’s collective even if the crowd is singing “Yellow Submarine” and it’s not overtly political. By contrast, drum circles are about improvisation, so each drummer can “do his own thing” while participating in the groupthink. (The “his” is implied: video of drum circles show few women participants. Apparently Janet Weiss, Meg White, and Sheila E.’s “own thing” can actually be done on their own.)

In terms of sound, drum circles also project well beyond their immediate location, compared to singing and chanting (in fact, OWS has had problems with the drum circles drowning out its “human microphone”). Plus, since the drummers can take breaks and change out, the actual drumming never stops, unlike a performing musician. Thus, drum circles are celebrations of self expression that are actively imposed on an audience that is well beyond eyesight. This summarizes a modern view of personality rooted in the 1960s: that it’s not enough to participate, you’ve also got to “be yourself.” I think these two notions account for the enduring idea of the drum circle as a supposedly political sound, even when it’s not. Drumming in a drum circle allows for a public display of self-expression that simultaneously allows the participant to belong to a group. The appeal of that is obvious, especially in our contemporary iCulture. However, the politicization of the sound of drum circles only makes sense when you add in the lingering sonic traces of black protest, modulated through a hippie lens. You can see this clearly in New York magazine’s “Bangin’: A Drum Circle Primer” (10.30.11), whose visual imagery prominently features a West African djembe drum and describes only the “hippie-era use of traditional African instruments” rather than their actual, snare-heavy configuration at OWS. Despite the snares and in spite of the oft-commented on lack of black faces at OWS—see Greg Tate’s piece in the Village Voice—drum circles still carry enough connotations of militant blackness to annoy the bourgeoisie.

One key thing differentiates OWS’s drummers from the demonstrations of yore, however: in the 60s and early 70s, there was a notion that drum circles were for drummers. Santana’s band, though young, was made up of world class musicians from the San Francisco scene. But to a certain type of viewer – young, white and male—the drum circle must have seemed so doable. Compared to the singular virtuosity of Jimi Hendrix or sheer talent of Pete Townshend, Santana’s music was the sonic equivalent of socialism. No wonder the drum circle scene has had more of a half-life in the hearts and minds of would-be Woodstockians than just about any other: it is a visceral depiction of music as communal, ecstatic, and accessible. Today, thanks to the far-reaching waves of the movie Woodstock: 3 Days of Peace & Music (1970), the percussive noise such a circle makes creates a particular sonic backdrop that clearly—and nostalgically—says hippiesomething.

And yet, politically speaking, nostalgia is, as theorists like Antonio Gramsci, Guy Debord, Jacques Attali and Theodor Adorno have frequently reminded us, invariably associated with Fascism. From Mussolini to Hitler to Reagan to Glenn Beck, it’s a tactic that has been explicitly invoked to thwart social progress. The nostalgia conundrum seems to have escaped both mainstream news media—which uses the drum circle to signify to viewers that OWS is a radical leftist plot—as well as the drummers themselves. For the drummers are hippies, and hippies young and old really believe in drum circles. Hippies take part in them, hippies enjoy them. It’s fair to say, however, that few others do, just as no one ever really enjoyed the 45- minute drum solos on live records by Cream, Led Zeppelin, and Iron Butterfly. (I’m thinking about Ginger Baker’s “Toad,” John Bonham’s “Moby Dick,” and “In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida,” respectively. Also about the time I went to the bathroom and bought popcorn at the LA Forum during a drum solo by some band I know forget, and still had to sit through ten more minutes.) .

However, that fact does not seem to bother those involved in drum circles, and herein lies the great problem with the whole equation drum + hippie = activism. To any members of the mainstream media who hears and records them, a drum circle instantly conjures up a chaotic, possibly even violent, scene: Chicago ‘68, Seattle 2000, Oakland 2011. But the truth is that, outside Fox News, the noun “hippie” no longer means “liberal,” or possibly even politically engaged. The curious thing about drum circles, then, is that while they sound progressive, they can actually mean conservative. A 2006 piece from NPR, for example, describes how drum circles have been adapted as teambuilding exercises for corporations like Apple, Microsoft, and McDonald’s.

The OWS situation illustrates such conservatism in different ways. In another recent article in New York Magazine, a 19 year old drummer from New Jersey is quoted as saying, “Drumming is the heartbeat of this movement. Look around: This is dead, you need a pulse to keep something alive.” This is said in the face of opposition from the movement’s own management, who fear a shutdown due to severe problems with neighborhood groups and restrictions on the General Assembly’s call-and-response “mic checks” that have been so galvanizing. His words are instructive as well as ominous, illustrating that young hippies like him believe that the sound of drums is a suitable replacement for protest or action itself.

The idea that sound alone can energize a movement is not just wrong, it also showcases a willful misunderstanding within the ranks of OWS. In Oakland last week, a small band of anarchists threw bottles at the police, whose wrath rained down in the form of tear gas canisters and a fusillade of dowels: one protester, an Iraq veteran, has been seriously injured.

The incident highlights a kind of cognitive dissonance that is hindering the ability of OWS to achieve political progress. The drumming problems at Zuccotti Park highlight the way that history can repeat itself as farce, as the distance between nostalgia and action — and between sound and meaning — disturbs the peace in more ways than one. Just as drummers in Sproul Plaza refuse to acknowledge that UC Berkeley is now mainly host to computer science and business majors, and drummers in Golden Gate Park refuse to deal with a Haight Ashbury that is gentrifying in front of their eyes, so too do the drummers at OWS refuse to acknowledge that their sound is no longer the sound of social activism. Indeed, the sound of a drum circle is reminiscent of the ring of a telephone, the scratch of a needle dropped on a record, or the clip clop of horse hoofs on hay-covered streets. No wonder it sounds out of place at OWS.

—

Gina Arnold recently received her Ph.D. in the program of Modern Thought & Literature at Stanford University, where she is currently a post doctoral scholar. Prior to beginning graduate work, she was a rock critic. Her dissertation, which draws on historical archives, literature, and films about counter cultural rock festivals of the 1960s and 1970 as well as on her own experience covering the less counter cultural rock festivals of the 1990s, is called Rock Crowds & Power. It is about rock crowds and power.

Garageland! Authenticity and Musical Taste

Today’s post is a bit of a confessional. Reflecting on Andreas Duus Pape’s post a few weeks back, Building Intimate Performance Venues on the Internet, I can not help but admire how closely Andreas relates podcasting with intimacy, and therefore; authenticity. Although it would be simple to critique this point as a case of circular reasoning (Podcasts are intimate because they are authentic. Podcasts are authentic because they are intimate.), I cannot help but wonder if there is something deeply honest and deftly earnest about this claim. Speaking as a musician, I believe that authenticity is a quality that cannot be conjured. It, like a feedback loop or proof of will, seeks only itself. But, how does the desire to be authentic shape performance? Does it affect what we listen for and who we listen to?

My adventures as a musician started in high school with a second hand guitar and a lot of free time. It only took a year before my pastime became something more like an obsession. First was my high school band: The Nosebleeds. The Nosebleeds played revved up versions of 50s and 60s rock and roll while all the other kids were covering Blink 182 and Operation Ivy. We were cool – really! Even at this early stage it was clear to me, authentic rock bands played old-school rock music. Even my punk guitar heroes from the 1970s like Mick Jones and Captain Sensible knew how to cop a Chuck Berry riff and Little Richard groove. After 3 years of humid Jersey shore dive bars and fluorescent high school talent shows we called it quits. Honestly, we just got bored. Also, our ace repertoire of fifteen songs was beginning to wear a little thin. . .

After The Nosebleeds came The Carpetbaggers. This was a sea-change in compositional direction. Instead of playing punky renditions of Twist and Shout, we affected a country twang and sang songs about travel and broken hearts. If you caught us on a good night, we would even throw a bit of Sonic Youth into the mix and evoke a wall of feedback out from silence. We played in New Brunswick basements and central Jersey bars and recorded an EP on an abandoned Tascam 1” reel to reel. Buzz words being thrown around at the time were: rootsy, alternative and raw. I had pulled the covers back from a revved up Chuck Berry only to find a wonderland of Americana – washboards, harmonicas, and acoustic guitars – waiting. This was, of course, what those rocker’s back in the day were inspired by – right? If The Carpetbaggers weren’t the real thing, who was?

When The Carpetbaggers broke up I joined one last band, The Acid Creeps. At this point, there would be no turning back from my descent into nostalgia. We aimed to resurrect the late sixties go-go bar house band. Taking care to acquire vintage Fender amplifiers, vintage reissue guitars, and even a knockoff Vox Continental organ. If that wasn’t enough, my sister sewed us matching orange paisley shirts which complimented our skinny black ties and sunglasses. We imagined ourselves as a period perfect garage band, exactly the sort we had seen in movies. We covered everything from Iggy Pop’s, I Wanna Be Your Dog, to The Sonic’s, Psycho, and the Detroit Wheels version of Little Latin Lupe Lu (which we all preferred). Only in our mid-twenties, we were experts (or snobs, depending on your perspective) at defining and defending what authentic garage music was, and what it was not. Before breaking up, we created a yellow 7” vinyl tomb to forever keep our music. It was named “The Bananna Split EP,” and at the moment it all seemed perfect. Authenticity, sold for five dollars at a show.

Reflecting, five years later, on these three epochs of music making – it is hard not to blush. Not only did I, for at least a year, consider each band the singular most authentic band ever; authenticity, as an ideal, began subtly to change the way I viewed myself. I transformed from Aaron the Weird Al Yankovic fan to Aaron, the garage rock expert in about 8 years. Wherever I looked for authenticity, I found it, and it was real. Not only that, but at the bar, we convinced ourselves and our friends of this notion. Conversations about which bands got it, and which did not, were frequent – if not mandatory. The answers became standard too: The Exploding Hearts, The Murder City Devils, The Misfits? They all got it. Bands like Metallica; for the most part, they did not. These conversations forever led us to equate the authentic with the obscure; a rabbit hole that twists and darts endlessly.

Authenticity in music is like feedback: powerful, seductive and dangerous. It is a very real, yet elusive concept that invites imitation and when left unchecked, can spread like a contagion. Although I love revisiting the music of my old bands, I cannot help but hear them now as a set of key moments in a greater life narrative. Iterations of myself left behind in an ongoing dialogue about authenticity. A dialogue, which, to this day, affects what music I choose to listen to, and what music I choose to avoid. Although none of my bands were truly “the real-deal,” it would be odd to claim that any were not authentic. Rather, this concept, authenticity animated each band – it kept us all going, and brought our music to life. My bands were authentic because I believed in them. I believed in my bands, because they were authentic.

AT

–

Aaron Trammell is co-founder and multimedia editor of Sounding Out! He is also a Media Studies PhD student at Rutgers University.

Recent Comments