Live Electronic Performance: Theory And Practice

This is the third and final installment of a three part series on live Electronic music. To review part one, “Toward a Practical Language for Live Electronic Performance” click here. To peep part two, “Musical Objects, Variability and Live Electronic Performance” click here.

“So often these laptop + controller sets are absolutely boring but this was a real performance – none of that checking your emails on stage BS. Dude rocked some Busta, Madlib, Aphex Twin, Burial and so on…”

This quote, from a blogger about Flying Lotus’ 2008 Mutek set, speaks volumes about audience expectations of live laptop performances. First, this blogger acknowledges that the perception of laptop performances is that they are generally boring, using the “checking your email” adage to drive home the point. He goes to express what he perceived to set Lotus’s performance apart from that standard. Oddly enough, it isn’t the individualism of his sound, rather it was Lotus’s particular selection and configuration of other artists’ work into his mix – a trademark of the DJ.

Contrasting this with the review of the 2011 Flying Lotus set that began this series, both reveal how context and expectations are very important to the evaluation of live electronic performance. While the 2008 piece praises Lotus for a DJ like approach to his live set, the 2011 critique was that the performance was more of a DJ set rather than a live electronic performance. What changed in the years between these two sets was the familiarity with the style of performance (from Lotus and the various other artists on the scene with similar approaches) providing a shift in expectations. What they both lack, however, is a language to provide the musical context for their praise or critique; a language which this series has sought to elucidate.

To put live electronic performances into the proper musical context, one must determine what type of performance is being observed. In the last part of this series, I arrive at four helpful distinctions to compare and describe live electronic performance, continuing this project of developing a usable aesthetic language and enabling a critical conversation about the artform. The first of the four distinctions between different types of live electronic music performance concerns the manipulation of fixed pre-recorded sound sources into variable performances. The second distinction cites the physical manipulation of electronic instruments into variable performances. The third distinction demarcates the manipulation of electronic instruments into variable performances by the programming of machines. The last one is an integrated category that can be expanded to include any and all combinations of the previous three.

Essential to all categories of live electronic music performance, however, is the performance’s variability, without which music—and its concomitant listening practices–transforms from a “live” event to a fixed musical object. The trick to any analysis of such performance however, is to remember that, while these distinctions are easy to maintain in theory, in performance they quickly blur one into the other, and often the intensity and pleasure of live electronic music performance comes from their complex combinations.

Flying Lotus at Treasure Island, San Francisco on 10-15-2011, image by Flickr User laviddichterman

For example, an artist who performs a set using solely vinyl with nothing but two turntables and a manual crossfading mixer, falls in the first distinction between live electronic music performances. Technically, the turntables and manual crossfading mixer are machines, but they are being controlled manually rather than performing on their own as machines. If the artist includes a drum machine in the set, however, it becomes a hybrid (the fourth distinction), depending on whether the drum machine is being triggered by the performer (physical manipulation) or playing sequences (machine manipulation) or both. Furthermore, if the drum machine triggers samples, it becomes machine manipulation (third distinction) of fixed pre-recorded sounds (first distinction) If the drum machine is used to playback sequences while the artist performs a turntablist routine, the turntable becomes the performance instrument while the drum machine holds as a fixed source. All of these relationships can be realized by a single performer over the course of a single performance, making the whole set of the hybrid variety.

While in practice the hybrid set is perhaps the most common, it’s important to understand the other three distinctions as each of them comes with their own set of limitations which define their potential variability. Critical listening to a live performance includes identifying when these shifts happen and how they change the variability of the set. Through the combination their individual limitations can be overcome increasing the overall variability of the performance. One can see a performer playing the drum machine with pads and correlate that physicality of it with the sound produced and then see them shift to playing the turntable and know that the drum machine has shifted to a machine performance. In this example the visual cues would be clear indicators, but if one is familiar with the distinctions the shifts can be noticed just from the audio.

This blending of physical and mechanical elements in live music performance exposes the modular nature of live electronic performance and its instruments. teaching us that the instruments themselves shouldn’t be looked at as distinction qualifiers but rather their combination in the live rig, and the variability that it offers. Where we typically think of an instrument as singular, within live electronic music, it is perhaps best to think of the individual components (eg turntables and drum machines) as the musical objects of the live rig as instrument.

Flying Lotus at the Echoplex, Los Angeles, Image by Flickr User sunny_J

Percussionists are a close acoustic parallel to the modular musical rig of electronic performers. While there are percussion players who use a single percussive instrument for their performances, others will have a rig of component elements to use at various points throughout a set. The electronic performer inherits such a configuration from keyboardists, who typically have a rig of keyboards, each with different sounds, to be used throughout a set. Availing themselves of a palette of sounds allows keyboardists to break out of the limitations of timbre and verge toward the realm of multi-instrumentalists. For electronic performers, these limitations in timbre only exist by choice in the way the individual artists configure their rigs.

From the perspective of users of traditional instruments, a multi-instrumentalist is one who goes beyond the standard of single instrument musicianship, representing a musician well versed at performing on a number of different instruments, usually of different categories. In the context of electronic performance, the definition of instrument is so changed that it is more practical to think not of multi-instrumentalists but multi-timbralists. The multi-timbralist can be understood as the standard in electronic performance. This is not to say there are not single instrument electronic performers, however it is practical to think about the live electronic musician’s instrument not as a singular musical object, but rather a group of musical objects (timbres) organized into the live rig. Because these rigs can be comprised of a nearly infinite number of musical objects, the electronic performer has the opportunity to craft a live rig that is uniquely their own. The choices they make in the configuration of their rig will define not just the sound of their performance, but the degrees of variability they can control.

Because the electronic performer’s instrument is the live rig comprised of multiple musical objects, one of the primary factors involved in the configuration of the rig is how the various components interact with one another over the time dependent course of a performance. In a live tape loop performance, the musician may use a series of cassette players with an array of effects units and a small mixer. In such a rig, the mixer is the primary means of communication between objects. In this type of rig however, the communication isn’t direct. The objects cannot directly communicate with each other, rather the artist is the mediator. It is the artist that determines when the sound from any particular tape loop is fed to an effect or what levels the effects return sound in relation to the loops. While watching a performance such as this, one would expect the performer to be very involved in physically manipulating the various musical objects. We can categorize this as an unsynchronized electronic performance meaning that the musical objects employed are not locked into the same temporal relations.

Big Tape Loops, Image by Flickr User choffee

The key difference between an unsynchronized and s synchronized performance rigs is the amount of control over the performance that can be left to the machines. The benefit of synchronized performance rigs is that they allow for greater complexity either in configuration or control. The value of unsynchronized performance rigs is they have a more natural and less mechanized feel, as the timing flows from the performer’s physical body. Neither could be understood as better than the other, but in general they do make for separate kinds of listening experiences, which the listener should be aware of in evaluating a performance. Expectations should shift depending upon whether or not a performance rig is synchronized.

This notion of a synchronized performance rig should not only be understood as an inter-machine relationship. With the rise of digital technology, many manufacturers developed workstation style hardware which could perform multiple functions on multiple sound sources with a central synchronized control. The Roland SP-404 is a popular sampling workstation, used by many artists in a live setting. Within this modest box you get twelve voices of sample polyphony, which can be organized with the internal sequencer and processed with onboard effects. However, a performer may choose not to utilize a sequencer at all and as such, it can be performed unsynchronized, just triggering the pads. In fact, in recent years there has been a rise of drum pad players or finger drummers who perform using hardware machines without synchronization. Going back to our three distinctions a performance such as this would be a hybrid of physical manipulation of fixed sources with the physical manipulation of an electronic instrument. From this qualification, we know to look for extensive physical effort in such performances as indicators of the the artists agency on the variable performance.

Now that we’ve brought synchronization into the discussion it makes sense to talk about what is often the main means of communication in the live performance rig – the computer. The ultimate benefit of a computer is the ability to process a large number of calculations per computational cycle. Put another way, it allows users to act on a number of musical variables in single functions. Practically, this means the ability to store, organize recall and even perform a number of complex variables. With the advent of digital synthesizers, computers were being used in workstations to control everything from sequencing to the patch sound design data. In studios, computers quickly replaced mixing consoles and tape machines (even their digital equivalents like the ADAT) becoming the nerve center of the recording process. Eventually all of these functions and more were able to fit into the small and portable laptop computer, bringing the processing power in a practical way to the performance stage.

Flying Lotus and his Computer, All Tomorrow’s Parties 2011, Image by Flickr User jaswooduk

A laptop can be understood as a rig in and of itself, comprised of a combination of software and plugins as musical objects, which can be controlled internally or via external controllers. If there were only two software choices and ten plugins available for laptops, there would be over seven million permutations possible. While it is entirely possible (and for many artists practical) for the laptop to be the sole object of a live rig, the laptop is often paired with one or more controllers. The number of controllers available is nowhere near the volume of software on the market, but the possible combinations of hardware controllers take the laptop + controller + software combination possibilities toward infinity. With both hardware and software there is also the possibility of building custom musical objects that add to the potential uniqueness of a rig.

Unfortunately, quite often it is impossible to know exactly what range of tools are being utilized within a laptop strictly by looking at an artist on stage. This is what leads to probably the biggest misnomer about the performing laptop musician. As common as the musical object may look on the stage, housed inside of it can be the most unique and intricate configurations music (yes all of music) has ever seen. The reductionist thought that laptop performers aren’t “doing anything but checking email” is directly tied to the acousmatic nature of the objects as instruments. We can hear the sounds, but determining the sources and understanding the processes required to produce them is often shrouded in mystery. Technology has arrived at the point where what one performs live can precisely replicate what one hears in recorded form, making it easy to leap to the conclusion that all laptop musicians do is press play.

Indeed some of them do, but to varying degrees a large number of artists are actively doing more during their live sets. A major reasons for this is that one of the leading Digital Audio Workstations (DAW) of today also doubles as a performance environment. Designed with the intent of taking the DAW to the stage, Ableton Live allows artists to have an interface that facilitates the translation of electronic concepts from the studio to the stage. There are a world of things that are possible just by learning the Live basics, but there’s also a rabbit hole of advanced functions all the way to the modular Max for Live environment which lies on the frontier discovering new variables for sound manipulation. For many people, however, the software is powerful enough at the basic level of use to create effective live performances.

Sample Screenshot from a performer’s Ableton Live set up for an “experimental and noisy performance” with no prerecorded material, Image by Flickr User Furibond

In its most basic use case, Ableton Live is set up much like a DJ rig, with a selection of pre-existing tracks queued up as clips which the performer blends into a uniform mix, with transitions and effects handled within the software. The possibilities expand out from that: multi-track parts of a song separated into different clips so the performer can take different parts in and out over the course of the performance; a plugin drum machine providing an additional sound source on top of the track(s), or alternately the drum machine holding a sequence while track elements are laid on top of it. With the multitude of plugins available just the combination of multi-track Live clips with a single soft synth plugin, lends itself to near infinite combinations. The variable possibilities of this type of set, even while not exploiting the breadth of variable possibilities presented by the gear, clearly points to the artist’s agency in performance.

Within the context of both the DJ set and the Ableton Live set, synchronization plays a major role in contextualization. Both categories of performance can be either synchronized or unsynchronized. The tightest of unsynchronized sets will sound synchronized, while the loosest of synchronized sets will sound unsynchronized. This plays very much into audience perception of what they are hearing and the performers’ choice of synchronization and tightness can be heavily influenced by those same audience expectations.

A second performance screen capture by the same artist, this time using pre-recorded midi sequences, Image by Flickr User Furibond

A techno set is expected to maintain somewhat of a locked groove, indicative of a synchronized performance. A synchronized rig either on the DJ side (Serato utilizing automated beat matching) or on the Ableton side (time stretch and auto bpm detection sync’d to midi) can make this a non factor for the physical performance, and so listening to such a performance it would be the variability of other factors which reveals the artist’s control over the performance. For the DJ, the factors would include the selection, transitions and effects use. For the Ableton user, it can include all of those things as well as the control over the individual elements in tracks and potentially other sound sources.

On the unsychronized end of the spectrum, a vinyl DJ could accomplish the same mix as the synchronized DJ set but it would physically require more effort on their part to keep all of the selections in time. This would mean they might have to limit exerting control on the other variables. An unsychronized Live set would be utilizing the software primarily as a sound source, without MIDI, placing the timing in the hands of the performer. With the human element added to the timing it would be more difficult to produce the machine-like timing of the other sets. This doesn’t mean that it couldn’t be effective, but there would be an audible difference in this type of set compared to the others.

What we’ve established is that through the modular nature of the electronic musician’s rig as an instrument, from synthesizer keyboards to Ableton Live, every variable consideration combines to produce infinite possibilities. Where the trumpet is limited in timbre, range and dynamics, the turntable is has infinite timbres; the range is the full spectrum of human hearing; and the dynamics directly proportional to the output. The limitations of the electronic musician’s instrument appear only in electrical current constraints, processor speed limits, the selection of components and the limitations of the human body.

Flying Lotus at Electric Zoo, 2010, Image by Flickr User TheMusic.FM

Within these constraints however, we have only begun touching the surface of possibilities. There are combinations that have never happened, variables that haven’t come close to their full potential, and a multitude of variables that have yet to be discovered. One thing that the electronic artist can learn from jazz toward maximizing that potential is the notion of play, as epitomized with jazz improvisation. For jazz, improvisation opened up the possibilities of the form which impacted, performance and composition. I contend that the electronic artist can push the boundaries of variable interaction by incorporating the ability to play from the rig both in their physical performance and giving the machine its own sense of play. Within this play lie the variables which I believe can push electronic into the jazz of tomorrow.

—

Featured Image by Flickr User Juha van ‘t Zelfde

—

Primus Luta is a husband and father of three. He is a writer and an artist exploring the intersection of technology and art, and their philosophical implications. In 2014 he will be releasing an expanded version of this series as a book entitled “Toward a Practical Language: Live Electronic Performance”. He is a regular guest contributor to the Create Digital Music website, and maintains his own AvantUrb site. Luta is a regular presenter for theRhythm Incursions Podcast series with his monthly showRIPL. As an artist, he is a founding member of the live electronic music collectiveConcrète Sound System, which spun off into a record label for the exploratory realms of sound in 2012.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Evoking the Object: Physicality in the Digital Age of Music–-Primus Luta

Experiments in Agent-based Sonic Composition–Andreas Pape

Calling Out To (Anti)Liveness: Recording and the Question of Presence—Osvaldo Oyola

Evoking the Object: Physicality in the Digital Age of Music

In our current relationship with technology, we bring our bodies, but our minds rule–Linda Stone, “Conscious Computing”

I begin with an epigraph from Linda Stone, who coined the phrase ‘continuous partial attention’ to describe our mental state in the digital age. The passive cousin of multi-tasking, continuous partial attention is a reaction to our constantly connected lifestyles in which everything is happening right now and where value is increasingly equated with our ability to digest it all. Almost everything we do has the potential to be interrupted, be it by an email, a text or a tweet; often we will give only partial attention to any one thing in anticipation of the next thing that will require our attention. In this internal fight for mental attention, listening to music has been seriously impacted.

The digital era has seen more music releases than ever before. Unfortunately, the massive influx of quantity is by no means a measure of how we are engaging with said music. iPhones and similar devices, for which music players have become mere features, enable listening to become a thing of partial attention. From allowing the shuffle or random modes to choose music selections for you, or even streaming music algorithms to calculate things you might like, to listening while playing Angry Birds or reading your Twitter stream, less commitment is made to the act of listening, and as such only a portion of our working memory is committed to the experience. Without working memory actively processing musical information, it is less likely to be stored for the long term, particularly if other information is continuously vying for space and attention.

These days video games sell better than music. Despite being a digital product, games are able to instill memories (even of the music) into one’s consciousness, because the game interface allows our sensory memories to work together in an active manner with the medium. Iconic memory stores visual cues from the game, echoic memory takes the audible cues from the game and the haptic memory is engaged in controlling game play. There is only so much more which can be done while playing a video game. If something were to interrupt game play, the game would be paused to address the new information rather than giving it partial attention. This is quite different from music which plays a background role in so much of our lives even when we are actively putting music on we tend to only engage it with partial attention.

When I began thinking about turning Concrète Sound System into a record label, one of my main goals was to create works that could engage the audience in active musical experiences that could create long term memories. I felt that as important as the music would be, it would take something material to create these memories, a physical product more evocative of earlier moments in recording history than the CD, its most recent gasp. I wondered if, by creatively evoking the physical object, the listener could be engaged in an active manner that would enable the memory of music and its power to persist through the everyday waves of digital noise.

The first mass duplicated audio medium was the Gold Moulded Edison Cylinder at the turn of the twentieth century. Imagine two cylinder copies of one of these recording today, as musical objects. Each of them would have over a hundred years of physical history. From the wear of the cases to the condition of the wax based on the temperature in which they were stored, each of these cylinders would be unique musical objects, with completely different histories, despite having the same origin. It is reasonable to assume that if the cylinders were played today on the same playback device, despite the fact that the compositions and performances are exactly the same, the differences between the recordings would be audible.

Wax Cylinders in the Library of Congress preservation Lab, Image by Flickr User Photo Phiend

Even without a century of history, there would likely be audible differences between the cylinders. If one cylinder was the first copy made, and another the 150th –master cylinders of Gold Moulded Edison Cylinders could only produce 150 copies reliably–the physical wear in the process of reproduction would leave its own imprint, making each of those copies distinct musical objects. In the analog world, as the technology improved the differences between copies decreased substantially. Cassettes were manufactured in batches of ten to hundreds of thousands without audible differences. But even in circulations so high, over time each of those analog copies took on their own identity and collected their own memories.

The listener as an active agent contributed to the development of these unique musical objects. After a purchase, any number of variables played into the ritual of the first experience of the music. Was there a way to listen upon walking out of the store? Were there liner notes or lyric sheets inside? Would you read those prior to listening or as you listen? Where would you listen? Through headphones? The listening chair in front of the hi-fi stereo? Or on the boombox with some friends? All of these possibilities shaped memories as musical objects that defined the music consumption culture of the past.

For example, I bought the debut 2Pac album 2Pacalypse Now on cassette the day it was released. I loved the album so much I kept it in regular rotation in my Walkman for months until finally the tape popped. Rather than go out and buy a new copy I decided to perform a surgery. It was in a screwless reel case which meant I couldn’t just open it up to retrieve the ends of the tape trapped inside, but rather had to crack the reel case open and transplant the reels into a new body. So, my copy of the 2Pacalypse Now cassette is now inside of a clear reel holder with no visual markings. It also has a piece of tape that was used to splice it back together, which makes an audible warp when played back. I can pretty much be sure that there is no other copy of 2Pacalypse which sounds exactly like mine. While this probably detracts from the resale value of the cassette (not that I’d sell it), it is imbued with a personal history that is priceless.

For example, I bought the debut 2Pac album 2Pacalypse Now on cassette the day it was released. I loved the album so much I kept it in regular rotation in my Walkman for months until finally the tape popped. Rather than go out and buy a new copy I decided to perform a surgery. It was in a screwless reel case which meant I couldn’t just open it up to retrieve the ends of the tape trapped inside, but rather had to crack the reel case open and transplant the reels into a new body. So, my copy of the 2Pacalypse Now cassette is now inside of a clear reel holder with no visual markings. It also has a piece of tape that was used to splice it back together, which makes an audible warp when played back. I can pretty much be sure that there is no other copy of 2Pacalypse which sounds exactly like mine. While this probably detracts from the resale value of the cassette (not that I’d sell it), it is imbued with a personal history that is priceless.

Cassettes, in particular, played a significant role in the attachment of physical memories to music beyond the recordings they held. They gave birth to the mixtape. The taper community was born from personal tape recorders that allowed concert-goers to record performances they attended, and, prior to the rise of peer to peer sharing online, these communities were trading tapes internationally via regular postal mail. European jazz and rock concerts were finding their way back to the states and South Bronx hip-hop performances were traveling with the military in Asia. All of these instances required a physical commitment with which came memories that inherently became their own musical objects.

Needless to say the nature of musical exchange has changed with the rise of the digital age of music. This is not to say that memories as musical objects have gone away, but they are being taken for granted as the objects lose their physicality. I remember going to The Wiz on 96th Street with $10 to spend on music. I spent at least ten minutes trying to decide between Sid and B-Tonn and Arabian Prince. I ended up with Arabian Prince and have regretted it since I got home and listened that day, as I never found Sid and B-Tonn for sale again. Today I could download both in the time it took me to walk to the train station. After skimming through the first few songs of Arabian Prince I could decide it was not for me and drag drop it in the trash where the memory of it would disappear with the files. No matter how I felt about the music then, the memory of it is a permanent fixture in my mind because of the physical actions it took to listen.

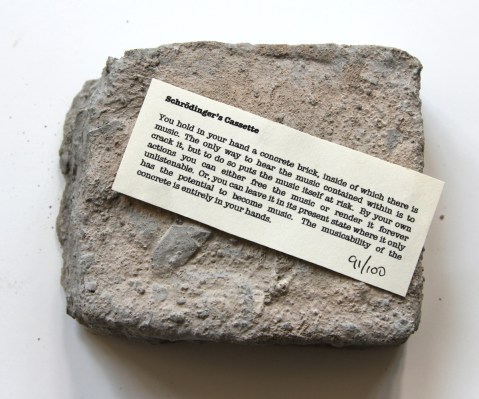

The first release for Concrète Sound System, Schrödinger’s Cassette, tackled this issue head on by presenting the audience with its own paradox, an update of physicist Erwin Schrödinger’s famous Thought Experiment, where the ultimate fate of the cassette inside is left up to the individual. Schrödinger’s Cassette sought to take listeners out of digital modes of consumption by using an analog medium to evoke the physical. The cassette release trend has been growing over the last few years, almost in parallel to the rise of the digital music and speaking to the need to separate music from our digital lives and to a desire to work harder for it. At the minimum, listening to a cassette requires having a cassette player, and acquiring one these days takes commitment. Unlike digital media, listeners cannot instantly skip a song on a cassette or put a favorite on repeat. It takes physical manipulation of the medium to move through its songs and doing so is a time investment. All these limitations make the cassette a medium that is best for linear listening, from beginning to end (unless you physically cut, rearrange, and splice it yourself).

Schrödinger’s Cassette, Image Courtesy of The Wire

Schrödinger’s Cassette took the required commitment a step further by encasing the cassette itself in industrial grade concrete. This required the user to actively crack the concrete (or the french concrète meaning ‘real’, from which the label derives its name) in order to listen to the music. The paradox is that, depending on the listener’s method for cracking, harm could be done to the cassette that might render it ‘unlistenable’. Upon receiving one of these pieces, the listener holds in their hands a musical object which they must physically act upon in order to create an unrepeatable musical event. Schrödinger’s Cassette has a look, a sound (if shaken you can hear the cassette reels), a feel, a smell, and a taste as well (though I wouldn’t advise it). All of the senses can be actively focused on the object and, as such, the whole of one’s working memory is engaged in the discernment of the object’s musical contents.

The Wire breaks open Schrödinger’s Cassette courtesy of their Twitterstream

For many, Schrödinger’s Cassette was taken as a work of art and left uncracked. The Wire magazine successfully cracked one edition open, revealing a portion of the musical contents on their regular radio program. For those that decided not to crack it, digital versions were made available so that they could listen, though this option was only made available after the listener spent some time with their physical object. In this way, the music from the project, a compilation called Between the Cracks, was directly connected to physical memories spurred by a material presence.

Triggering active memory during the consumption of music through physical objects need not be this complex. Old medium such as vinyl and cassette releases inherently have the physical properties required without the concrete or much else. Perhaps for this reason they show new signs of life despite the rise of digital. No matter how much our reality is augmented by our digital lives, we still inhabit those bodies that we bring with us, and, as far as the memories those bodies carry with them go, physicality rules.

—

Featured Image: Wax Cylinders in the Library of Congress, Image by Flickr User Photo Phiend

—

Primus Luta is a husband and father of three. He is a writer and an artist exploring the intersection of technology and art, and their philosophical implications. He is a regular guest contributor to theCreate Digital Music website, and maintains his own AvantUrb site. Luta is a regular presenter for the Rhythm Incursions Podcast series with his monthly showRIPL. As an artist, he is a founding member of the live electronic music collectiveConcrète Sound System, which spun off into a record label for the exploratory realms of sound in 2012.

ISSN 2333-0309

Translate

Recent Posts

- Top Ten Sounding Out! Posts of 2025!

- SO! Reads: Marisol Negrón’s Made in NuYoRico: Fania Records, Latin Music, and Salsa’s Nuyorican Meanings

- Finding Resonance, Finding María Lugones

- Press Play and Lean Back: Passive Listening and Platform Power on Nintendo’s Music Streaming Service

- “A Long, Strange Trip”: An Engineer’s Journey Through FM College Radio

Archives

Categories

Search for topics. . .

Looking for a Specific Post or Author?

Click here for the SOUNDING OUT INDEX. . .all posts and podcasts since 2009, scrollable by author, date, and title. Updated every 5 minutes.

Recent Comments