Sound and Curation; or, Cruisin’ through the galleries, posing as an audiophiliac

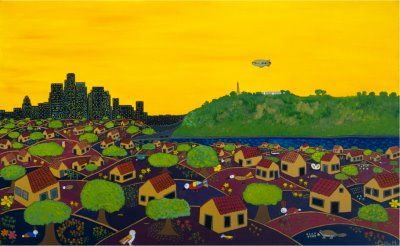

“L.A. Reimagined” by Dalila Paola Mendez (c), Mendez’ work will be featured in re:present LA, opening 5/3/12

But to love this turf is love hard and unrequited.

…

To love L.A. is to love more than a city

It’s to love a language.

–“L.A. Love Cry” (1996) by Wanda Coleman

Los Angeles, an enigmatic metropolis to many who arrive here with a dream in hand and hope for a better tomorrow, still challenges historians, artists, and troubadours on how to best represent it. Poet Wanda Coleman, born in Watts, captures the pain and wonder of loving this city in “L.A. Love Cry.” Because the city is “hard and unrequited” one must also be willing to love its nuances and see it as“more than a city.” To love this city, “it’s to love a language,” a cultural immersion that goes beyond the seeming ease of words into the complexities of sound and rhythm.

Through a Museum Studies course I teach at Claremont Graduate University entitled Welcome to L.A., I introduce students to varied texts in which scholars and artists challenge the imaginaries created by outsiders, boosters, and apocalyptic cinema. Instead, the course readings present how we in L.A. actively engage with one another by fostering communities of creative praxis. For the students’ final project, they curate and develop educational programming for an exhibition at a local museum or art center. On May 3, 2012, this semester’s project, re : present L.A., opens at the newly-renovated Vincent Price Art Museum (VPAM) located on the East Los Angeles College Campus. Showing works from over thirty artists from May 3-July 27, re : present L.A serves as an extension of the conversations we had in class, not only celebrating the interconnectedness of our communities but encouraging new associations and encounters within the visual and resonant space of VPAM’s Community Focus Gallery. For a look at the Virtual Exhibit Catalogue, click here.

In each exhibition for Welcome to L.A., I try to include something that challenges myself to think outside the white-box, per se, of the gallery. Given that we had read several texts that highlighted in the importance of music to build and uplift communities of color in Los Angeles, it was both important and necessary for me to include sonic elements in re: present LA that exhibits L.A.s vibrant musical legacy as intermingled with and fundamental to its visual culture. Among the challenges to document the cross-cultural connections between ethnic communities in Los Angeles is how to unpack what Anthony Macias calls “the cultural networks” that facilitated these exchanges through the music scenes at music halls, clubs, youth centers and record stores in Mexican American Mojo (10-11). Studies done by George Lipsitz, Macias, and Victor Viesca, provide readers a means to understand how the music in Los Angeles is much more than entertainment; it is political; it is a lifestyle; it defines spaces of multicultural interactions. In How Racism Takes Place, Lipsitz points out how integral the reclamation of space defined the political outlook and music in Horace Tapscott’s Arkestra based in South L.A. Viesca’s research documents the rise of an East L.A. rock sound, post-Los Lobos, that was defined by the activism of the Zapatista Movement and California’s Prop 187 through the work done at the Peace & Justice Center, Self-Help Graphics, and Regeneración.

Therefore, in order to engage both the history and the sound of Los Angeles’s musics with the city’s visual representations, I invited Rubén Funkhuatl Guevara from Ruben & The Jets, is a multi-threat musician, performer, writer, and producer, and Jennifer Stoever-Ackerman (of Binghamton University, Sounding Out!, and of course, Riverside, CA) to curate playlists for a “sound booth,” which will consist of a stationary iPod™ Nano that gallery visitors can use at their leisure. The classic circular wheel allows the viewer to advance tracks or play the playlists on shuffle. Headphones will be set up so that the viewer can either focus on their listening experience or, listen while viewing the artwork around them. Since the gallery is relatively small, the pieces on the opposite wall are recognizable though are distant. In addition, Maya Santos of Form Follows Function will screen their short documentary on Radiotron, a youth center that presented Hip-Hop shows during the 1980s.

Guevara’s playlist Los Angeles Chicano Rock & Roll is included in the exhibition thanks to the Museum of Latin American Art. Stoever-Ackerman’s playlist Off the 60, unites the two spaces of East L.A. and Riverside through a mix of intra- and trans-cultural musical experiences. Guevara’s rock & roll selections highlight many of the bands that emerged in East L.A. Both the musical listings and the liner notes for the sound presentations will be accessible on the re:present L.A website when the exhibit goes live on May 3rd, 2012.

Juan Capistran’s The Breaks (2000), Courtesy of the Artist

.

My sonic intervention in the white, often silent, spaces of the gallery was especially inspired by two recent precedents: the inclusion of the iPod™ in MEX/LA (2011) at the Museum of Latin American Art and Phantom Sightings (2008) at the Los Angeles County Art Museum. Both experiences invited me as a viewer to see the artwork through another sensory experience. The first time I saw music included in an exhibition not specifically about music (such as the Experience Music Project’s 2007 American Sabor: Latinos in U.S. Popular Music, or Marvette Peréz’s curation of ¡Azúzar! The Life and Music of Celia Cruz at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History) was LACMA’s Phantom Sightings, which garnered much critical acclaim and criticism due to the premise of presenting contemporary Chicano Art inspired ‘after’ the Chicano Movement. However, I want to focus on one aspect of the exhibition, a corner display with books that informed the curators’ conceptual approach and on the bookshelf was an iPod™. The iPod™ included playlists from some of the artists reflecting their inspiration for their artwork. I enjoyed listening and reminiscing while sitting in the gallery. However, I wanted the music to take more of a central role in the exhibition, especially because much of the artwork so obviously revealed traces of Los Angeles’ musical influences, partly due to the recent generation of artists who actively engaged in subcultural expressions and referenced it in their art. For example, as Ondine Chavoya describes in the Phantom Sightings catalogue, Juan Capistran’s The Breaks (2000) is a giclée print documenting the artist break-dancing on Carl Andre’s minimalist floor pieces. The guerilla performance then is presented through a series of twenty-five still images showing the various movements seen in how to break-dance books (125). Shizu Saldamando’s ink on fabric portraits of Siouxsie (2005) and Morrissey (2005) showcase how post-punk and new wave music from England is part of her life as an Angeleno (and that of her friends), yet the medium is reminiscent of pinto drawings. Saldamando also does portraits of her friends at clubs, backyard bbqs “documenting a world where identity is fluid” as Michele Urton describes in the catalog (197).

Shizu Saldamando’s Siouxsie (2005), Courtesy of the Artist

It would be another three years before MEX/LA would further marry music with art, now casting it in relation to the politics of Chicano and Mexican presence in Los Angeles. MEX/LA, among the many Pacific Standard Time exhibitions presented throughout Los Angeles, was among the best curated due to the range of artifacts representative of the city and the cultural production emerging in post-war L.A. Another striking element was the influence of Méxicano popular culture among Chicanos and vice-versa. As curator Rubén Ortiz-Torres, and associate curator Jesse Lerner write on the MoLAA website: “The purpose of the construction of a ‘Mexican’ identity in the South of California is not to consolidate the national unity of a post-revolutionary Mexico, but to recognize and be able to participate in an international reality, with all its contradictions and conflicts that this entails.” One of the ways this cultural exchange was embodied was in the playlists curated by Rubén Funkhuatl Guevara and Josh Kun that were prominently displayed alongside the artwork and heard in the interactive iPod™ “sound booths,” that invited viewers to sit on beanbags and listen. The music served to contextualize the art in relation to popular culture of the time. For example, Guevara presents a Chicano rock & roll genealogy that followed the chronology of the visual exhibit, 1930-1980, that begins with boogaloo and swing of the 1940s era culminating with the punk rock sounds of The Bags.

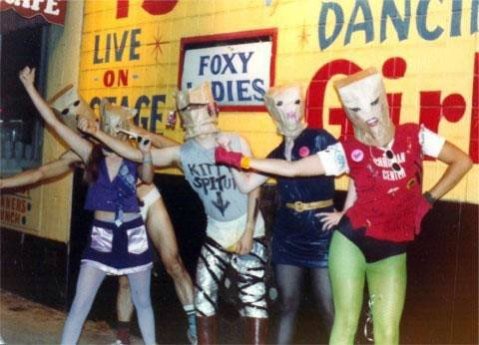

“Bag Parade,” 1977, Courtesy of Alice Bag

In both these exhibitions, the music served to complement the artistic elucidations of identity, race, and American popular culture seen in much of the artwork. The simplicity of the presentation was due to the inclusion of a familiar object like the iPod™. What is surprising is that more exhibitions have not incorporated more sonic elements to engage viewers’ other sensory experiences beyond the podcasts, or cell-phone audio listening tours set up at most major museums. While musical playlists can serve as another didactic component of an exhibition like the more established audio tours, I am arguing for a different use of sound in museum space, one that provides a wider sense of agency, connection, and encounter with the visual elements on display rather than a one-way transmission of information. In the cases of MEX/LA and Phantom Sightings, the inclusion of iPods™ provided a tool to understand the cultural production of a “post-Chicano movement” generation of artists while at the same time enabling an experience that recognized—and resonated with—my bicultural experience.

“Ancient Mexico in Ancient Mexico” by Yvonne Estrada (c), is featured in re:present LA, opening 5/3/12

Being that L.A. is a car culture moving to the rhythms of the radio waves, I’m always seeking to find synchronicity between music that feels me with joy and my work as a cultural worker. Part of my impetus to locate Los Angeles sonically in re : present L.A. was driven by the question: is it possible to capture my sonic landscape growing up in the city of Los Angeles that ranges from Hip-Hop – British Rock – Mexican Pop? The playlists curated by Guevara and Stoever-Ackerman are familiar to me personally. Stoever-Ackerman’s Off the 60, reminds me of the sounds of my youth, when KDAY and KROQ rocked the radio waves and my students banded together in my high school quad according to their favorite music – metal-heads, b-boys, alternative rock, and the cha-chas, who traveled across town every Friday night to Franklin High, where DJs spun L.A. disco. At home, the music was different. My mom and tías used to reminisce about their homeland every Sunday night through the variety show Siempre en Domingo, binding us to the t.v., religiously following the rising stars. Through the bi-lingual selections in Guevara’s Los Angeles Rock & Roll, there’s a familiarity of home and the music heard at backyard parties and quinceañeras.

By including my iPod™ nano, I bring together my lived experience as a cultural worker through the sounds of L.A. and activate the white walls of the museum. The playlists created by Guevara and Stoever-Ackerman serve to reflect the history of the community surrounding VPAM, as well capture the diversity of the city sonically re:presenting L.A. to our audiences. While the playlists can stand alone as audio curations in their own rights, I hope that they will engage audiences to rethink the relationship between music and art, and feel their lived experience inclusive within the museum.

—-

reina alejandra prado saldivar is an art historian, curator, and an adjunct lecturer in the Social Science Division of Glendale Community College in Glendale, California and in the Cultural Studies Program at Claremont Graduate School. As a cultural activist, she focused her earlier research on Chicano cultural production and the visual arts. Prado is also a poet and performance artist known for her interactive durational work Take a Piece of my Heart as the character Santa Perversa (www.santaperversa.com) and is currently working on her first solo performance entitled Whipped!

Recent Comments