SO! Reads: Danielle Shlomit Sofer’s Sex Sounds: Vectors of Difference in Electronic Music

Distance, therefore, preserves a European austerity in recorded musical practices, and electroacoustic practice is no exception; it is perhaps even responsible for reinvigorating a colonial posterity in contemporary music as so many examples in this book follow this pattern–Danielle Shlomit Sofer, Sex Sounds, 14.

Sex Sounds: Vectors of Difference in Electronic Music (MIT Press, 2022) by Danielle Shlomit Sofer brings a complex analysis for contemporary de-colonial, queer and feminist readers. This book did its best to sustain an argument diving into eleven case studies and strongly problematising the Western white cis gaze. Sofer offers readers a new perspective in both the history of music and the decolonisation of that history.

In a moment when discussions of consent, censorship, pleasure, and surveillance are reshaping how we think about media, Sofer asks: What does sex sound like, and why does it matter? Their analysis cuts across high art and popular culture, from avant-garde compositions to pop music to porn, revealing how sonic expressions of sex are never neutral—they’re deeply entangled in gendered, racialized, and heteronormative structures. In doing so, Sex Sounds resonates with broader critical work on listening as a political act, aligning with ongoing conversations in sound studies about the ethics of hearing and the politics of voice, noise, and silence

The main focus of Sex Sounds is the historical loop of sexual themes in electronic music since the 1950s. Sofer writes from the perspective of a mixed-race, nonbinary Jewish scholar specializing in music theory and musicology. They argue that the way the Western world teaches music history involves hegemonic narratives. In other words, the author’s impetus is to highlight the construction of mythological figures such as Pierre Schaeffer in France and Karlheinz Stockhausen in Germany who represent the canon of the Eurocentric music phenomena.

Sex Sounds specifically follows the concept of “Electrosexual Music,” defined by Sofer as electroacoustic Sound and Music interacting with sex and eroticism as socialized aesthetics. The issue of representation in music is a key research focus navigating questions such as: “How does music present sex acts and who enacts them? ” as well as: “how does a composer represent sexuality? How does a performer convey sexuality? And how does a listener interpret sexuality?” (xxiv & xxix). Moreover, Sofer traces: “the threats of representation, namely exploitation and objectification” (xxxvii) as the result of white male privilege and the historical harm and violence this means (xiix & 271).

By exploring answers to these questions, Sofer successfully exposes how electroacoustic sexuality has historically operated as a constant presence in many music genres, as well as proving that music and sound did not begin in Europe nor belongs only to the Anglo-European provincial cosmos. Sex Sounds gives visibility to peripheral voices ignored by the Eurocentric canon, arguing for a new history of music where countries such as Egypt, Ghana, South Africa, Chile, Japan or Korea are central.

Sofer further vivisects the meaning of sexual sounds as not only Eurocentric and colonial but patriarchal and sexist. What is the history behind sex sounds in the electroacoustic music field? Can we find liberation in sex sounds or have they only reproduced dominance? Which role do sex sounds play in the territories of otherness and racial representation? Are there examples where minoritized people have reclaimed their voice? Sex is part of our humanity. But how do sex sounds dehumanize female subjects? These are more of the fundamental questions Sofer responds to in this study.

I aim, first and foremost, to show that electrosexual music is far representative a collection than the typically presented electroacoustic figures -supposedly disinterested, disembodied, and largely white cis men from Europe and North America –Sofer, Sex Sounds,(xvi).

The time frame of the study ranges from 1950 until 2012, analysing four case studies. Sofer divides the book in two parts: Part I: “Electroacoustics of the Feminized Voice” and Part II: “Electrosexual Disturbance.” The first part contextualizes “electrosexual” music within the dominant cis white racial frame. The main argument is to demonstrate how many canonic electroacoustic works in the history of Western sound have sustained an ongoing dominance as a historical habit locating the male gaze at the center as well as instrumentalizing the ‘feminized voice’ as mere object of desire without personification and recognition as fundamental actor in the compositions. Under such a premise, Sofer vivisects sound works such as “Erotica” by the father of Musique Concretè Pierre Schaffer and Pierre Henry (1950-1951), Luc Ferrari’s “les danses organiques” (1973) and Robert Normandeu’s “Jeu de Langues” (2009), among other pieces.

Luc Ferrrari’s work from 1973 is one of many examples in which Sofer makes evident the question of consent, since the women’s voices he includes were used in his work without their knowledge, a pattern of objectivation that mirrors structures of patriarchal domination. Sofer “defines and interrogates the assumed norms of electroacoustic sexual expression in works that represent women’s presumed sexual experience via masculinist heterosexual tropes, even when composed by women” (xivii-xiviii). Sofer emphasises the existence of “distance” as a gendered trope in which women’s audible sexual pleasure is presented as “evidence” in the form of sexualized and racialized intramusical tropes. Philosophically speaking, this phenomena, Sofer argues, goes back to Friedrich Nietzsche and his understanding of the “women’s curious silence” (xxvii). In other words, a woman can be curious but must remain silent and in the shadows.

This is the case in Schaeffer and Henry’s “Erotica” (1950-1951), one of the earliest colonial impetus to electrosexual music in which female voices are both present and erased, present in the recording but erased as subjects of sonic agency, since the composers did not credit the woman behind the voice recordings. She has no name nor authorship, but her sexualized voice is the main element in the composition. This paradox shows the issue of prioritising the ‘Western’ white European cis male gaze. This gaze uses women’s sexuality as a commerce where only the composer benefits from this use. This exposes the problem of labor and exploitation within electroacoustic practice historically dominated by white men.

“Erotica” stands out for its sensual tension, abstract eroticism, and experimental use of the body as both subject and instrument. This work belongs to the hegemonic narrative of electroacoustic music with the use of sex sounds as aesthetic objects that insinuate erotic arousal as a construct of the male gaze.

Through examples like “Erotica” Sofer strongly questions the exclusion of women as active agents of aesthetic sonic creation since: “electroacoustic spaces have long excluded women’s contributions as equal creators to men, who are more typically touted as composers and therefore compensated with prestige in the form of academic positions or board dominations” (xxxix). This book considers: “the threats of representation, namely exploitation and objectification” (xxxvii). Here we navigate the questions of how something is presented, by whom, and with which profit or intention. In other words, how sounds: “are created, for what purposes, and in turn, how sounds are interpreted and understood” (xxxiii).These are problems rooted in both patriarchy and capitalism.

This book is a strong contribution to decolonize the history of music as we know it, although the citations here could be richer, including studies by Rachel McCarthy (“Marking the ‘Unmarked’ Space: Gendered Vocal Construction in Female Electronic Artists” 2014), Tara Rodgers (“Tinkering with Cultural Memory: Gender and the Politics of Synthesizer Historiography” 2015), and the work of Louise Marshall and Holly Ingleton, who used intersectional feminist frameworks to analyze the work of marginalized composers (including women of color) and the curatorial practices that shape electronic music history. Also, not to forget: Chandra Mohanty’s “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses” (1988).

Musical artist Sylvester

I argue that, although many composers of color work in electronic music, the search term ‘electroacoustic’ remains exclusionary because of who declares themselves as an advocate of this music, and not necessarily in how their music is made–Sofer, Sex Sounds, (xiv).

After a deep dive into the genealogy of the patriarchal practices in electroacoustic music understood as electrosexual works (hence: “Sex is only re-presented in music p. xxix), Sofer moves to the territory of feminist contra-narratives. In the second part of their study, Sofer offers sonic practices and concrete examples that: “break the electroacoustic mold either by consciously objecting to its narrow constraints or by emerging from, building on, and, in a sense, competing with a completely different historical trajectory” (xlvi). Contra-narratives from the racialized periphery and underground landscapes appear in this book as case studies to hold the argument and expand the homocentric and patriarchal telos found even in the sonic archives as well as the Western theoretical corpus. These ‘Others’ reclaim their voices going a step further and gaining recognition.

After examining examples of racialisation and objectification, Sofer selects some case studies from 1975 to 2013 in the second chapter of this section titled: “Electrosexual Disturbance.” In this section, Sofer also points to new forms of exclusion and instrumentalisation via “racial othering,” specifically in the context of popular music such as Disco where we find an emphasis on the feminized voice. Disco, as a genre rooted in Black, queer, and marginalized communities, inherently grappled with racial and gendered dynamics. Donna Summer’s “Love to Love You Baby” (1975) exemplifies this tension.

The track’s erotic vocal performance (23 simulated orgasms over 16 minutes) became emblematic of the hypersexualization of Black women in popular music. Summer’s persona as the “first lady of love” reinforced stereotypes of Black female sexuality as inherently exotic or excessive, a trope traced to racist and sexist historical narratives. Simultaneously, disco provided a space for liberation: Black and LGBTQ+ artists like Summer, Sylvester, and Gloria Gaynor used the genre to assert agency over their identities and bodies, challenging mainstream exclusion. The tropes of sex and race are a paradoxical combination bringing both oppression as well as liberation.

Sofer argues that Summers was commercially recognized but her figure as a composer was destroyed, creating consequently a hierarchy of labor. She was acknowledged for her amazing sexualized voice and performance on stage, but not recognized as a musician or equal to music producers. Here we see the practice of epistemological discrimination and extreme racial sexualisation. On the positive side, Summer became the Black Queen idol for gay liberation. Nevertheless, she remained as the sexualized and racial voice of the seventies.

Sofer also presents the case of ex-sex worker, sex-educator and radical ecosex-activist Annie Sprinkle collaborating in a post-porn art video with the legendary Texan and lesbian composer Pauline Oliveros. For Sprinkle and Oliveros, Sofer offers a different phenomena at work, since both queer-women/Lesbian-women collaborated from the point of feminist independence and sexual liberation coming together for educational purposes.

Sluts & Goddesses (1992) is a porn film with an Oliveros soundtrack, produced by radical women– with only women–in a self-determined frame. The movie offers an example of collaboration moving from avantgarde sound composition expertise to trashy whoring and interracial lesbian power. This example was rare, but inspiring for the coming generations. Two lesbian Titans united for electrosexual disturbance from the feminist gaze, Sprinkle and Oliveros were a duo that broke silence.

This book revisits the acousmatic in its electronic manifestations to examine and interrogate sexual and sexualized assumptions underwriting electroacoustic musical philosophies.–Sofer, Sex Sounds, (xxi)

Sofer’s Sex Sounds enters into a vital and still-emerging conversation about how sound—particularly sonic expressions of sex and eroticism—shapes, disrupts, and reinscribes power. At a time when sonic studies increasingly reckon with embodiment, affect, and intimacy, Sofer brings a feminist and queer critique to the center of how we listen to, interpret, and culturally regulate the sounds of sex. Their book invites us to reconsider not only what we hear in erotic audio, but how we’ve been taught—socially, politically, morally—to hear it.

This book doesn’t just fill a gap—it pushes the field toward a more nuanced, bodily-aware mode of scholarship. For SO! readers, Sex Sounds offers both a provocation and a methodology: it challenges us to hear differently, to ask how power works not only through what is seen or said, but through what is moaned, whispered, muffled, or made to be heard too loudly.

—

Featured Image: “Stamen,” by Flickr User Sharonolk, CC BY 2.0

—

Verónica Mota Galindo is an interdisciplinary researcher based in Berlin, where they study philosophy at the Freie Universität. Their work goes beyond the academic sphere, blending sound art, critical epistemology, and community engagement to make complex philosophical ideas accessible to broader audiences. As a dedicated educator and sound artist, Mota Galindo bridges the gap between academic research and lived material experience, inviting others to explore the transformative power of critical thought and creative expression. Committed to bringing philosophy to life outside traditional boundaries, they inspire new ways of thinking aimed at emancipation of the human and non-human for collective survival.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

Into the Woods: A Brief History of Wood Paneling on Synthesizers*–Tara Rodgers

Ritual, Noise, and the Cut-up: The Art of Tara Transitory—Justyna Stasiowska

SO! Reads: Zeynep Bulut’s Building a Voice: Sound, Surface, Skin –Enikő Deptuch Vághy

What Feels Good to Me: Extra-Verbal Vocal Sounds and Sonic Pleasure in Black Femme Pop Music

The lyrics to Beyoncé’s 2008 song “Radio” treats listening pleasure as a thinly-veiled metaphor for sexual pleasure. For example, they describe how turning up a car stereo transforms it into a sex toy: “And the bassline be rattlin’ through my see-eat, ee-eats/Then that crazy feeling starts happeni-ing- i-ing OH!” Earlier in the song, the lyrics suggest that this is a way for the narrator to get off without arousing any attempts to police her sexuality: “You’re the only one that Papa allowed to hang out in my room/…And mama never freaked out when she heard it go boom.” Because her parents wouldn’t let her be alone in her bedroom with anyone or anything that they recognized as sexual, “Radio”’s narrator finds sexual pleasure in a practice that isn’t usually legible as sex. In her iconic essay “On A Lesbian Relationship With Music,” musicologist Suzanne Cusick argues that if we “suppose that sexuality isn’t necessarily linked to genital pleasure” and instead “a way of expressing and/or enacting relationships of intimacy through physical pleasure shared, accepted, or given” (70), we can understand the physical pleasures of listening to music, music making, and music performance as kinds of sexual pleasure.

Though Cusick’s piece overlooks the fact that sexual deviance has been, since the invention of the idea of sexuality in the late 19th century, thoroughly racialized, her argument can be a good jumping-off point for thinking about black women’s negotiations of post-feminist ideas of sexual respectability; it focuses our attention on musical sound as a technique for producing queer pleasures that bend the circuits connecting whiteness, cispatriarchal gender, and hetero/homonormative sexuality. In an earlier SO! Piece on post-feminism and post-feminist pop, I defined post-feminism as the view that “the problems liberal feminism identified are things in…our past.” Such problems include silencing, passivity, poor body image, and sexual objectification. I also argued that post-feminist pop used sonic markers of black sexuality as representations of the “past” that (mostly) white post-feminists and their allies have overcome. It does this, for example, by “tak[ing] a “ratchet” sound and translat[ing] it into very respectable, traditional R&B rhythmic terms.” In this two-part post, I want to approach this issue from another angle. I argue that black femme musicians use sounds to negotiate post-feminist norms about sexual respectability, norms that consistently present black sexuality as regressive and pre-feminist.

Black women musicians’ use of sound to negotiate gender norms and respectability politics is a centuries-old tradition. Angela Davis discusses the negotiations of Blues women in Blues Legacies & Black Feminism (1998), and Shana Redmond’s recent article “This Safer Space: Janelle Monae’s ‘Cold War’” reviews these traditions as they are relevant for black women pop musicians in the US. While there are many black femme musicians doing this work in queer subcultures and subgenres, I want to focus here on how this work appears within the Top 40, right alongside all these white post-feminist pop songs I talked about in my earlier post because such musical performances illustrate how black women negotiate hegemonic femininities in mainstream spaces.

Black women musicians’ use of sound to negotiate gender norms and respectability politics is a centuries-old tradition. Angela Davis discusses the negotiations of Blues women in Blues Legacies & Black Feminism (1998), and Shana Redmond’s recent article “This Safer Space: Janelle Monae’s ‘Cold War’” reviews these traditions as they are relevant for black women pop musicians in the US. While there are many black femme musicians doing this work in queer subcultures and subgenres, I want to focus here on how this work appears within the Top 40, right alongside all these white post-feminist pop songs I talked about in my earlier post because such musical performances illustrate how black women negotiate hegemonic femininities in mainstream spaces.

As America’s post-identity white supremacist patriarchy conditionally and instrumentally includes people of color in privileged spaces, it demands “normal” gender and sexuality performances for the most legibly feminine women of color as the price of admission. As long as black women don’t express or evoke any ratchetness–any potential for blackness to destabilize cisbinary gender and hetero/homonormativity, to make gender and sexuality transitional–their expressions of sexuality and sexual agency fit with multi-racial white supremacist patriarchy.

It is in this complicated context that I situate Nicki Minaj’s (and in my next post Beyoncé’s and Missy Elliott’s) recent uses of sound and their bodies as instruments to generate sounds. If, as I argued in my previous post, the verbal and visual content of post-feminist pop songs and videos is thought to “politically” (i.e., formally, before the law) emancipate women while the sounds perform the ongoing work of white supremacist patriarchy, the songs I will discuss use sounds to perform alternative practices of emancipation. I’m arguing that white bourgeois post-feminism presents black women musicians with new variations on well-worn ideas and practices designed to oppress black women by placing them in racialized, gendered double-binds.

For example, post-feminism transforms the well-worn virgin/whore dichotomy, which traditionally frames sexual respectability as a matter of chastity and purity (which, as Richard Dyer and others have argued, connotes racial whiteness), into a subject/object dichotomy. This dichotomy frames sexual respectability as a matter of agency and self-ownership (“good” women have agency over their sexuality; “bad” women are mere objects for others). As Cheryl Harris argues, ownership both discursively connotes and legally denotes racial whiteness. Combine the whiteness of self-ownership with well-established stereotypes about black women’s hypersexuality, and the post-feminist demand for sexual self-ownership puts black women in a catch-22: meeting the new post-feminist gender norm for femininity also means embodying old derogatory stereotypes.

For example, post-feminism transforms the well-worn virgin/whore dichotomy, which traditionally frames sexual respectability as a matter of chastity and purity (which, as Richard Dyer and others have argued, connotes racial whiteness), into a subject/object dichotomy. This dichotomy frames sexual respectability as a matter of agency and self-ownership (“good” women have agency over their sexuality; “bad” women are mere objects for others). As Cheryl Harris argues, ownership both discursively connotes and legally denotes racial whiteness. Combine the whiteness of self-ownership with well-established stereotypes about black women’s hypersexuality, and the post-feminist demand for sexual self-ownership puts black women in a catch-22: meeting the new post-feminist gender norm for femininity also means embodying old derogatory stereotypes.

I think of the three songs (“Anaconda,” “WTF,” and “Drunk in Love”) as adapting performance traditions to contemporary contexts. First, they are part of what both Ashton Crawley and Shakira Holt identify as the shouting tradition, which, as Holt explains, is a worship practice that “can include clapping, dancing, pacing, running, rocking, fainting, as well as using the voice in speaking, singing, laughing, weeping, yelling, and moaning.” She continues, arguing that “shouting…is also a binary-breaking performance which confounds—if only fleetingly—the divisions which have so often oppressed, menaced, and harmed them.” These vocal performances apply the shouting tradition’s combination of the choreographic and the sonic and binary-confounding tactics to queer listening and vocal performance strategies.

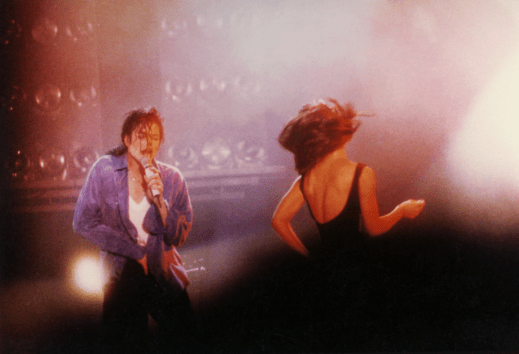

Francesca Royster identifies such strategies in both Michael Jackson’s work and her audition of it. According to Royster, Jackson’s use of non-verbal sounds produces an erotics that exceeds the cisheteronormative bounds of his songs’ lyrics. They were what allowed her, as a queer teenager, to identify with a love song that otherwise excluded her:

in the moments when he didn’t use words, ‘ch ch huhs,’ the ‘oohs,’ and the ‘hee hee hee hee hees’…I ignored the romantic stories of the lyrics and focused on the sounds, the timbre of his voice and the pauses in between. listening to those nonverbal moments–the murmured opening of “Don’t Stop Till You Get Enough,” or his sobbed breakdown at the end of “She’s Out of My Life,’ I discovered the erotic (117).

Royster references a black sexual politics in line with Audre Lorde’s notion of the erotic in “The Uses of the Erotic,” which is bodily pleasure informed by the implicit and explicit knowledges learned through lived experience on the margins of the “European-American male tradition” (54), and best expressed in the phrase “it feels right to me” (54). Lorde’s erotic is a script for knowing and feeling that doesn’t require us to adopt white supremacist gender and sexual identities to play along. Royster calls on this idea when she argues that Jackson’s non-verbal sounds–his use of timbre, rhythm, articulation, pitch–impart erotic experiences and gendered performances that can veer off the trite boy-meets-girl-boy-loses-girl stories in his lyrics. “Through his cries, whispers, groans, whines, and grunts, Jackson occupies a third space of gender, one that often undercuts his audience’s expectations of erotic identification” (119). Like shouting, “erotic” self-listening confounds several binaries designed specifically to oppress black women, including subject/object binaries and binary cisheterogender categories.

Nicki Minaj uses extra-verbal sounds as opportunities to feel her singing, rapping, vocalizing body as a source of what Holt calls “sonophilic” pleasure, pleasure that “provide[s] stimulation and identification in the listener” and invites the listener to sing (or shout) along. Minaj is praised for her self-possession when it comes to business or artistry, but such self-possession is condemned or erased entirely when discussing her performances of sexuality. As Treva B. Lindsey argues, “the frequency that Nicki works on is not the easiest frequency for us to wrestle with, because it’s about…whether we can actually tell the difference between self-objectification and self-gratification.’’ Though this frequency may be difficult to parse for ears tempered to rationalize post-feminist assumptions about subjectivity and gender, Minaj uses her signature wide sonic pallette to shift the conversation about subjectivity and gender to frequencies that rationalize alternative assumptions.

In her 2014 hit “Anaconda,” she makes a lot of noises: she laughs, snorts, trills her tongue, inhales with a low creaky sound in the back of her throat, percussively “chyeah”s from her diaphragm,among other sounds. The song’s coda finds her making most of the extraverbal sounds. This segment kicks off with her quasi-sarcastic cackle, which goes from her throat and chest up to resonate in her nasal and sinus cavities. She then ends her verse with a trademark “chyeah,” followed by another cackle. Then Minaj gives a gristly, creaky exhale and inhale, trilling her tongue and then finishing with a few more “chyeah”s. While these sounds do percussive and musical work within the song, we can’t discount the fact that they’re also, well…fun to make. They feel good, freeing even. And given the prominent role the enjoyment of one’s own and other women’s bodies plays in “Anaconda” and throughout Minaj’s ouevre, it makes sense that these sounds are, well, ways that she can go about feelin herself.

Listening to and feeling sonophilic pleasure in sounds she performs, Minaj both complicates post-feminism’s subject/object binaries and rescripts cishetero narratives about sexual pleasure. “Anaconda” flips the script on the misogyny of Sir Mix-a-Lot’s hit “Baby Got Back” by sampling the track and rearticulating cishertero male desire as Nicki’s own erotic. First, instead of accompanying a video about the male gaze, that bass hook now accompanies a video of Nicki’s pleasure in her femme body and the bodies of other black femmes, playing as she touches and admires other women working out with her. Second, Nicki re-scripts the bass line as a syllabification: “dun-da-da-dun-da-dun-da-dun-dun,” which keeps the pattern of accents on 1 and 4, while altering the melody’s pitch and rhythm.

Just as “Anaconda”’s lyrics re-script Mix-A-Lot’s male gaze, so do her sounds. If the original hook sonically orients listeners as cishetero “men” and “women,” Nicki’s vocal performance reorients listeners to create and experience bodily pleasure beyond the “legible” and the scripted. Though the lyrics are clearly about sexual pleasure, the sonic expression or representation of that pleasure–i.e., the performer’s pleasure in hearing/feeling herself make all these extraverbal sounds–makes it physically manifest in ways that aren’t conventionally understood as sexual or gendered. Because it veers off white ciseterogendered scripts about both gender and agency, Minaj’s performance of sonophilia is an instance of what L.H. Stallings calls hip hop’s “ratchet imagination.” This imagination is ignited by black women’s dance aesthetics, wherein “black women with various gender performances and sexual identities within the club, on stage and off, whose bodies and actions elicit new performances of black masculinity” renders both gender and subject/object binaries “transitional” (138).

Nicki isn’t the only black woman rapper to use extra-verbal vocal sounds to re-script gendered bodily pleasure. In my next post, I’ll look at Beyoncé and Missy Elliot’s use of extra-vocal sounds to stretch beyond post-feminism pop’s boundaries.

—

Featured image: screenshot from “Anaconda” music video

—

Robin James is Associate Professor of Philosophy at UNC Charlotte. She is author of two books: Resilience & Melancholy: pop music, feminism, and neoliberalism, published by Zer0 books last year, and The Conjectural Body: gender, race and the philosophy of music was published by Lexington Books in 2010. Her work on feminism, race, contemporary continental philosophy, pop music, and sound studies has appeared in The New Inquiry, Hypatia, differences, Contemporary Aesthetics, and the Journal of Popular Music Studies. She is also a digital sound artist and musician. She blogs at its-her-factory.com and is a regular contributor to Cyborgology.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

“I Love to Praise His Name”: Shouting as Feminine Disruption, Public Ecstasy, and Audio-Visual Pleasure–Shakira Holt

Music Meant to Make You Move: Considering the Aural Kinesthetic–Imani Kai Johnson

Something’s Got a Hold on Me: ‘Lingering Whispers’ of the Atlantic Slave Trade in Ghana–Sionne Neely

Recent Comments