SO! Reads: Jonathan Sterne’s MP3: The Meaning of a Format

The point that had lingered with me after first reading Jonathan Sterne’s essay “The mp3 as Cultural Artifact,” was the idea that the mp3 was a promiscuous technology. “In a media-saturated environment,” Sterne writes, “portability and ease of acquisition trumps monomaniacle attention . . . at the psychoacoustic level as well as the industrial level, the mp3 is designed for promiscuity. This has been a long-term goal in the design of sound reproduction technologies” (836). A technology, promiscuous? I did not have to look far to find support. Like germs, I could find copies of mp3s that I had downloaded from Napster in 2000 scattered across generations of my old hard drives. Often they were redundant, too – iTunes having archived a copy separate from my original download.

The point that had lingered with me after first reading Jonathan Sterne’s essay “The mp3 as Cultural Artifact,” was the idea that the mp3 was a promiscuous technology. “In a media-saturated environment,” Sterne writes, “portability and ease of acquisition trumps monomaniacle attention . . . at the psychoacoustic level as well as the industrial level, the mp3 is designed for promiscuity. This has been a long-term goal in the design of sound reproduction technologies” (836). A technology, promiscuous? I did not have to look far to find support. Like germs, I could find copies of mp3s that I had downloaded from Napster in 2000 scattered across generations of my old hard drives. Often they were redundant, too – iTunes having archived a copy separate from my original download.

But, for Sterne, mp3s are also socially promiscuous. They accumulate in the hard drives of the working class and are shared, almost anywhere, through the branching left/right wires of iPod earbuds. Since the popularization of the mp3, there have been new opportunities to share how we listen with others. This is promise of the mp3, and the reason it forms such a key point of scholarly meditation.

MP3: The Meaning of a Format (Duke University Press, 2012) finds Sterne revisiting many of these key themes, with a larger focus on the genealogical beginnings of the mp3 technology. While many of the book’s chapters are extrapolations of prior work Sterne has done regarding the genealogy of listening practices, this work concerns itself less with the 19th century, and more with the 20th century. Perhaps this is related to some of the methodological decisions Sterne has made in planning the book – in seeking out the genealogical origins of the mp3, Sterne worked from archives and manuals described in interviews by engineers who were fundamental to the technology’s production. As such it finds much in common with Trevor Pinch and Frank Trocco’s Analog Days and Dave Tompkins’ How to Wreck a Nice Beach but incorporates the genealogical methods regarding sonic technology present in Sterne’s earlier work The Audible Past and Emily Thompson’s The Soundscape of Modernity. In MP3 Sterne positions himself as a critical cultural studies scholar working between the humanities and sciences, focusing specifically on the mp3 due to its social and technological relevance today. The critical is key here as MP3 is truly a work devised to underscore the economic connections between the construction of our selves as “hearing subjects” and the media industries.

MP3: The Meaning of a Format (Duke University Press, 2012) finds Sterne revisiting many of these key themes, with a larger focus on the genealogical beginnings of the mp3 technology. While many of the book’s chapters are extrapolations of prior work Sterne has done regarding the genealogy of listening practices, this work concerns itself less with the 19th century, and more with the 20th century. Perhaps this is related to some of the methodological decisions Sterne has made in planning the book – in seeking out the genealogical origins of the mp3, Sterne worked from archives and manuals described in interviews by engineers who were fundamental to the technology’s production. As such it finds much in common with Trevor Pinch and Frank Trocco’s Analog Days and Dave Tompkins’ How to Wreck a Nice Beach but incorporates the genealogical methods regarding sonic technology present in Sterne’s earlier work The Audible Past and Emily Thompson’s The Soundscape of Modernity. In MP3 Sterne positions himself as a critical cultural studies scholar working between the humanities and sciences, focusing specifically on the mp3 due to its social and technological relevance today. The critical is key here as MP3 is truly a work devised to underscore the economic connections between the construction of our selves as “hearing subjects” and the media industries.

Certainly, the mp3 can still be considered a promiscuous technology, but it is corporate capitalism that had failed to recognize the extent to which it relies on technological promiscuity to support its infrastructure. This focus, ironically, displaces the mp3 as the main object of Sterne’s analysis. It highlights instead the pathological logic of corporate capitalism, and the ways that this rationality has mutated, now, in the wake of mass replicable, malleable, and iterative digital culture. In other words, the mp3 is endemic to a much larger plot, wherein the culture industries adapt to their own deus ex-machina. The naive development of the mp3 by the motion picture industry is a large part of the story here, but it is only a small bit of a much larger whole. The real story involves understanding how a handful of vested corporate interests have shaped the ways that we interpret and understand what listening is. In MP3 Sterne addresses one of the great questions of sound studies: What are the politics of listening? Or, which individuals and institutions have a vested economic interest in questions of how we hear?

Sterne recalls this drama in three parts, each unfolding in a somewhat autonomous fashion, but unified in so far as they explore the economic interests behind the scientific construction of “hearing subjects.” In the first part, Sterne is at his best exploring AT&T’s (and the affiliated Bell Laboratories’) role in funding psychological, physiological, and cybernetic research on hearing. In the second, Sterne explains how this early research has been applied to the visual and technical abstraction of sound in the 1970s. And, in the third part of this genealogy, he explains how these analogs were made digital, specifically the corporate politics which went into the construction of the mp3 standard. Throughout this surprising and detailed trajectory, Sterne makes the invisibility of corporate interests apparent and explicit.

Sterne also hints toward several powerful economic rationalities that have guided the construction of the mp3. Key among these insights is the monetization of cybernetic discourse, or the incorporation of the human body within a scientific understanding of technical systems. In order to engineer an efficient technical system, the capacities and limits of how we interact with (or serve as parts of) these systems must be taken into account. Sterne refers to this mode of engineering as “perceptual technics,” and he goes to great lengths to explain it.

Basically, at the turn of the 20th century, AT&T had taken a keen interest in the science of how people listen because they wanted to maximize the amount of simultaneous conversations broadcast through a single telephone wire. More conversations meant the purchase of fewer wires, and therefore greater profits. Eventually, drawing on the research of the oft-cited Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver (within SO!: What Mixtapes Can Teach Us About Nois and Pushing Record; and soundBox: Mapping Noise), AT&T recognized an economic problem of technical efficiency within their wires – there was too much ambient noise. Because of this, AT&T sought to limit the audible signal transmitted from one phone to another. This would allow for more signals (and therefore conversations) to be transmitted through the same wire. Physiological research provided clues that some frequencies were more audible than others, so engineers worked to compress audio signals to reflect this scientific abstraction of hearing.

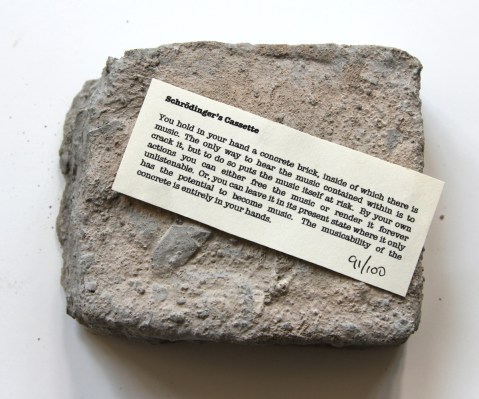

The reduction of listening–as an embodied practice–to the quantification and control of the audible spectrum, is, in other words, the history of compression. Which, according to Sterne, should be understood as the true meaning of the mp3. While the mp3 format, like the CD or cassette, may become obsolete, technologies of compression will not. Sterne argues convincingly that most advances in compression technologies have been guided by the invisible logic of corporate capitalism. It is this exact tendency of compression–to make things smaller and more efficient–that threatened to undo the entire project of corporate and branded music distribution in the year 2000, via platforms like Napster. Sterne is well aware of this irony throughout MP3, and uses the final chapter to discuss, briefly, the moment of cultural transformation that is defined by file-sharing and mass distribution.

Bringing things full circle with a somewhat stoic conclusion about the democratic potentials of this moment, he remarks: “The end of the artificial scarcity of recording is a moment of great potential. Its political outcome is still very much in question, but its political meaning should not be” (224). Sterne points to the globalization and ubiquity of mediated listening as a sign that things may not have changed much even though mass networked society at one point promised freedom from a commodity form which privileged things like “liberal notions of property, alienated labor, and ownership” (224). He argues that even the music industries shall persevere, mostly because people have a sublime attraction to listening and music. In other words: Meet the new boss, same as the old boss. There are few moments of liberation to be found within MP3; it is instead a drama of the status quo where the conspirators of corporate capitalism succeed in spite of themselves.

The ubiquity of listening. Borrowed from κεηι on Flickr.

The disparity in Sterne’s tone, when juxtaposing the nefarious and efficient dispositifs of capitalism with an untroubled and authentic construction of music is striking to say the least. And although Sterne is clear to explain that he locates his scholarship as work on a container technology (the mp3) and not its content (the music), this is a somewhat unsatisfying distinction as an embodied practice, such as listening, must take both into account. And while I agree that the mp3 reflects the promiscuity of corporate capitalism, is this challenged by the plethora of ideological nuance coded into song lyrics and arrangements? Do the corporate ideologies of the music industries flow beyond the container of the mp3 into the music itself? Is there any crosstalk, or overlap between these historical constructions? In other words, what are the limits to theorizing a container technology, and how much does the discursive path of the mp3 sculpt the content of what we listen to?

Despite, or perhaps, because of the rather dystopic scene that Sterne alludes to at the end of MP3, it falls nicely in the space between Sound Studies and Critical Information Studies. It bridges humanistic scholarship on embodied listening practices with a critique of the economic interests that have funded much of the scientific research relating to the phenomenology of sound. To that end, MP3 reveals much about the social construction of hearing and the ways that the familiar mythology of audio fidelity has been produced, discussed and exploited by several communication industries. Even though the mp3 may have been eclipsed by industry as the main object of inquiry in the eponomously titled MP3, Sterne succeeds admirably in detailing the promiscuity of corporate capitalism in the listening practices of our everyday lives.

–

Aaron Trammell is co-founder and Multimedia Editor of Sounding Out! He is also a Media Studies PhD candidate at Rutgers University.

For example, I bought the debut 2Pac album

For example, I bought the debut 2Pac album

Recent Comments