SO! Reads: Kirstie Dorr’s On Site, In Sound: Performance Geographies in América Latina

“World Music,” both as a concept and as a convenient marketing label for the global music industry, has received a fair deal of deserved criticism over the last two decades, from scholars and musicians alike. In his famous 1999 op-ed, David Byrne wrote that the term is “a none too subtle way of reasserting the hegemony of Western pop culture. It ghettoizes most of the world’s music.” Ethnomusicologists have aldo challenged the othering power of this term, inviting us to listen to “worlds of music” and “soundscapes” as the culture of particular places and times, suggesting that these sonic encounters with difference might teach “us” (in “the West”) to consider how our own musical worlds are situated in social and historical processes.

“World Music,” both as a concept and as a convenient marketing label for the global music industry, has received a fair deal of deserved criticism over the last two decades, from scholars and musicians alike. In his famous 1999 op-ed, David Byrne wrote that the term is “a none too subtle way of reasserting the hegemony of Western pop culture. It ghettoizes most of the world’s music.” Ethnomusicologists have aldo challenged the othering power of this term, inviting us to listen to “worlds of music” and “soundscapes” as the culture of particular places and times, suggesting that these sonic encounters with difference might teach “us” (in “the West”) to consider how our own musical worlds are situated in social and historical processes.

While this has been an important move toward recognizing the multiplicity of musicking practices (rather than reinforcing a monolithic “Other” genre), the study of “musical cultures” runs the risk of territorializing musical “traditions.” Linking them to geographically delineated points of origin, nations or homelands that are made to seem natural, fixed, or timeless often overlooks the heterogeneity of places, essentializing the people who make and listen to music within, across, and in relation to their ever-changing borders. The challenge for music critics and scholars has been–and still is–to delegitimize the alienating broad brush of the “world music” label without resorting to a classification system that reifies music production and circulation into exotic genres or fetishized “local” traditions.

In her 2018 book, On Site, In Sound: Performance Geographies in América Latina(Duke University Press), Kirstie A. Dorr demonstrates a method for conceptualizing relations between music and space while avoiding the pitfalls of colonial and capitalist definitions of “culture” and “identity.” She takes the term “performance geography” from Sonjah Stanley Niaah, whose discussion of Jamaican dancehall employs this analytic as “a mapping of the material and spatial conditions of performance: entertainment and ritual in specific sites/venues, types and systems of use, politics of their location in relations to other sites and other practices, the character of events/rituals in particular locations, and the manner in which different performances/performers relate to each other within and across different cultures” (Stanley Niaah 2008: 344). Dorr looks at “musical transits” rather than musical cultures, focusing on the politics and relations within sound and performance across South America and its diasporas; one particular relation serves as the central argument of the book: “that sonic production and spatial formation are mutually animating processes” (3).

In her 2018 book, On Site, In Sound: Performance Geographies in América Latina(Duke University Press), Kirstie A. Dorr demonstrates a method for conceptualizing relations between music and space while avoiding the pitfalls of colonial and capitalist definitions of “culture” and “identity.” She takes the term “performance geography” from Sonjah Stanley Niaah, whose discussion of Jamaican dancehall employs this analytic as “a mapping of the material and spatial conditions of performance: entertainment and ritual in specific sites/venues, types and systems of use, politics of their location in relations to other sites and other practices, the character of events/rituals in particular locations, and the manner in which different performances/performers relate to each other within and across different cultures” (Stanley Niaah 2008: 344). Dorr looks at “musical transits” rather than musical cultures, focusing on the politics and relations within sound and performance across South America and its diasporas; one particular relation serves as the central argument of the book: “that sonic production and spatial formation are mutually animating processes” (3).

Three conceptual frames help Dorr follow the musical flows that push against national and regional boundaries sounded by the global music industry: listening, a form of attention toward the interplay of sensory content, form, and context; musicking, or conceptualizations of music-making in terms of relationships and creative practices, rather than the musical “works” they produce and commodify; and performance as “a technique of action/embodiment that. . .potentially reshapes social texts, relationships, and environments” (14-16). Through close listenings to performances in Peru, San Francisco, and less emplaced sites such as YouTube and the “Andean Music Industry,” Dorr makes a strong case for performance geographies as creative decolonial strategies, both for participants in musical transits and for scholars who imagine and invent the boundaries and trajectories of musicking practices.

***

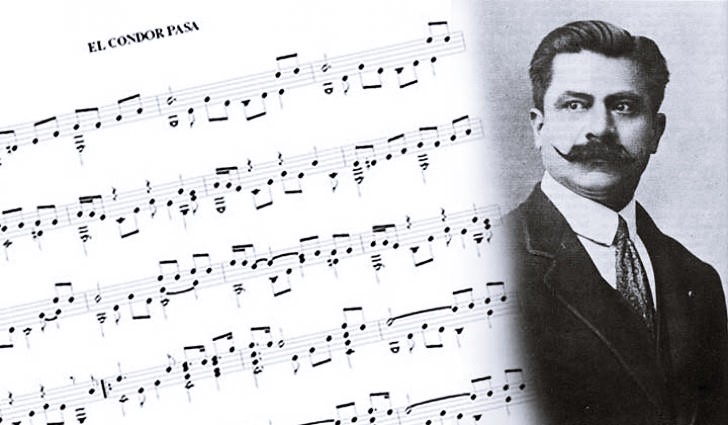

Nearly a century after Peru won its independence from Spain, limeño playwright Julio Baudouin debuted El Cóndor Pasa, a two-act play promoting national unity through a tale of indigenous miners in a struggle against their foreign bosses. The play’s score, composed by musician and folklorist Daniel Alomía Robles, weaves Peruvian highland music into Western-style arrangements and instrumentation, and was widely received by its 1913 audience as the sound of what Peru was to become: a modern nation firmly rooted in the cultures of its indigenous peoples.

Daniel Alomía Robles

In the century that followed, the score’s homonymous ballad has been interpreted and recorded by countless artists around the world. Easily the most well-known rendition of this famous melody is Simon and Garfunkel’s “El Cóndor Pasa (If I Could),” (1970) which Dorr credits with catalyzing a Latin American music revival as well as spurring on a wave of Euro-American musicians and producers who collaborated with and brought into the international spotlight a number of groups who otherwise would have remained in relative obscurity. The tendency to see these projects as the work of (typically white) Westerners “discovering” and “saving” or paternalistically “curating” the dying musical cultures of the world, Dorr suggests, is part and parcel of a World Music concept that frames “primitive” traditions as fair game for extraction and appropriation into innovative sonic hybrids.

15 Nov 1991, Paris, France — Peruvian singer Yma Sumac

The “exotica” category follows the same logic, as the case of Yma Sumac illustrates. From the beginning of her career in the early 1940s with el Conjunto Folklórico Peruano to her 1971 psychedelic version of “El Cóndor Pasa,” Sumac’s vocal versatility and stylistic experimentations map out an experience of Andean indigeneity that Dorr hears in stark contrast to the narratives of the global music industry. While Capitol Records performed their own geography via their marketing of this sexualized “Incan princess,” the singer strategically composed her own sonic-spatial imaginary, not rejecting the difference suggested by “exotica,” but by synthesizing a “space-age” modern aesthetic with traditional songs. Dorr challenges us to listen to Sumac’s “El Cóndor Pasa” against Simon’s arrangement, thinking of her performative dissonances as disruptions of “the static geotemporal imaginaries of ‘authentic indigeneity’ that have most often informed the ballad’s deployment” (59).

If Chapter One makes a case for performance’s potential to shape notions of place and time, Chapter Two explores “spatial(ized) relations of musicking” (68) through a broader consideration of market strategies and the politics of sound in public space. Putumayo serves as another classic example of the global music industry’s pandering to multicultural idealism, promoting itself as “lifestyle company” that brings conscious capitalism into the curation of musical worlds. Dorr keeps her critique of Putumayo rather brief, but uses it as a convincing contrast for the focus of this chapter: the informal streams of economic activity and performance that she calls the “Andean music industry” (AMI). Among other examples from transnational and virtual “sites,” the Andean bands that performed in San Francisco’s Union Square throughout the 1990s demonstrate how performance geographies can challenge state and capitalist power while simultaneously running parallel to the marketing and distribution practices of the world music industry.

The AMI story is one of migration and the formation of a pan-Andean diaspora, of busking and bootlegging tactics that tested the boundaries of zoning and noise regulations as well as California’s immigration and labor policies, and of transposing music networks onto the internet when public performance became too precarious. It is also another case of dissonance, in which musicians willfully use their own cultural difference to their advantage, but not without consequences for poor musicians in South America; a telling example is the “Music of the Andes” CD, a mass-produced compilation used by various groups who, instead of having to record and press their own albums, could simply print their own covers for the Putumayoesque compilation and sell them to their none-the-wiser U.S. audiences (84).

But if the diasporic politics of the AMI came up short in challenging a monolithic representation of “Andean culture” or in highlighting the dynamic transits of Andean fusions such as chicha and Nueva Canción, the daily performances of street musicians in the race- and class-ordered Union Square support Dorr’s argument about the co-constitutive relationship between sound and space: “This unmediated display of embodied and sonic ‘otherness’ threatened the coherence of the square’s representational function by converting it into a spectacle of work and play for a population upon whose concealed labor the economic foundations of California’s wealth largely depend: undocumented migrant workers from the global South” (81).

Busking in Union Square, 2013, Image by Flickr User Dr. Bob Hall

Elsewhere in 1990s San Francisco, musicians, artists, and activists formed a collective that, like the busking Andean groups, challenged dominant notions of public and private space while performing its own transnational and migratory experiences of Latinidad. In Chapter 4, Dorr relates the story of La Peña del Sur, a grassroots organization in the Mission District and, like the many anti-imperialist peñas popular throughout Latin America since the 1960s, a space for artists to perform or display their work for local audiences. While this peña provided a community for undocumented immigrants and local residents threatened by gentrification, it also served as an unsettling force against the sort of geographies that separate “queer space” from “heterosexual space” without regard for how these neighborhoods are also classed and racialized.

The founder and director of La Peña del Sur, Chilean exile Alejandro Stuart, was among several queer community members whose efforts constituted their shared space as a challenge to normative boundaries, a site for musicking that engendered dialogue among a wide range of people with divergent visions and motivations. Community organizers and students of cultural sustainability would do well to read Dorr’s account of this decade-long experiment that “enabled the exploration of sound-based solidarities rooted in the identification of common historical and political ground through improvisation and participatory performance” (168).

Victoria Santa Cruz, Image courtesy of Flickr User “Traveling Man”

Between these two compelling tales of the dynamic relationship of sound and space in San Francisco, Chapter 3 explores the significance of race, nation, gender, and sexuality within the performance geographies of several Afro-Peruvian artists. Dorr traces the movements of performers and activists who challenged the colonial boundaries that framed blackness as “antithetical to the emergent nation” (111); unlike the indigenous traditions that could be appropriated for an imagining of Peru as modern yet firmly rooted in history, Afro-Peruvian bodies and sounds were treated as contaminants within the postcolonial order.

Listening to Black feminist performance geographies, from Peru’s Black Arts Revival in the ’60s and ’70s to the recent hemispheric collaborations of “global diva” Susana Baca, one can hear the formation of not only such racially imagined communities as “the coastal” and the “Afro-Latinx diaspora,” but also of “the body.” A powerful case of this latter sort of performance is heard in the lyrics and experiences of Victoria Santa Cruz, who, in her choreographed, cajón- and chorus-accompanied poem, “Me Gritaron Negra,” contests the ways in which “[t]he physical contours of her body – her lips and skin and hair – become a geography inscribed with social meaning, an ideological imposition intended to enact and legitimate her ongoing displacement” (121).

Santa Cruz’s pedagogical and performative practices, in particular, reveal why Dorr has chosen sound – and not only broader analytics of performance and musicking – as a central theme to explore in terms of its relation to places and bodies. While this book might leave a few sound studies scholars wanting more elaborate description of particular sonic phenomena or ethnographic consideration of how sound is imagined among Dorr’s interlocutors, a few examples in particular are keys to thinking about how sound signifies, and is signified by, racially mapped bodies and places.

Most intriguing here is a discussion of Santa Cruz’s 1971 book, Discovery and Development of a Sense of Rhythm, which outlines the artist’s approach to “listen[ing] with the body” and tuning in to “rhythm’s Afro-diasporic logics” (116). A pedagogy and practice developed well in advance of Henri Lefebvre’s theory of rhythmanalysis, Santa Cruz’s concept of ritmo–internal rhythm— deserves consideration alongside the work of Amiri Baraka, Jon Michael Spencer, Fred Moten, and Daphne Brooks as crucial for thinking about how Black aesthetics and diasporic sensibilities are cultivated through sound and capable of mobilizing new mappings of bodies and their worlds.

Victoria Santa Cruz, still from el programa de La Chola Chabuca. (Video: América TV)

On Site, In Sound also calls for renewed thinking on sonic-spatial relations and the meanings that emerge from within them – how the sounds of particular Latin American voices and instruments come to be understood as masculine or feminine, indigenous or modern, exotic or local. Although “sound” as a specific performative or sensory medium might seem, at times, only one among many phenomena examined within the book’s threefold conceptual framing – listening, musicking, and performance – Dorr weaves it throughout her own performance geography where it takes on multiple forms and scales, challenging even the very boundaries defining what sound “is.” More importantly, this is a geography that scholars of “the sonic” or “music worlds” should read (and hear) as a reminder of sound’s unique ability to create and transcend boundaries – but rarely without a great deal of dissonance.

—

Featured Image: “Gabriel Angelo, Union Square,” by Flickr User Brandon Doran

—

Benjamin Bean is a PhD student in sociocultural anthropology at The University of California, Davis. His research interests include Afro-Caribbean music and sound, food and the senses, Puerto Rico, religion and secularism, and the Rastafari movement. During his undergraduate studies at Penn State Brandywine and graduate studies in cultural sustainability at Goucher College, Ben’s fieldwork focused on reggae music, the performativity of Blackness, and the Rastafari concepts of Word, Sound, and Power and I-an-I. His current fieldwork in Puerto Rico examines flavor, taste, and marketing in the island’s growing craft beer movement. Ben was formerly a vocalist and bass guitarist with the Philadelphia-based roots reggae band, Steppin’ Razor.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

SO! Reads: Dolores Inés Casillas’s ¡Sounds of Belonging!–Monica De La Torre

SO! Reads: Roshanak Khesti’s Modernity’s Ear–Shayna Silverstein

SO! Reads: Licia Fiol-Matta’s The Great Woman Singer: Gender and Voice in Puerto Rican Music–Iván Ramos

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Recent Comments